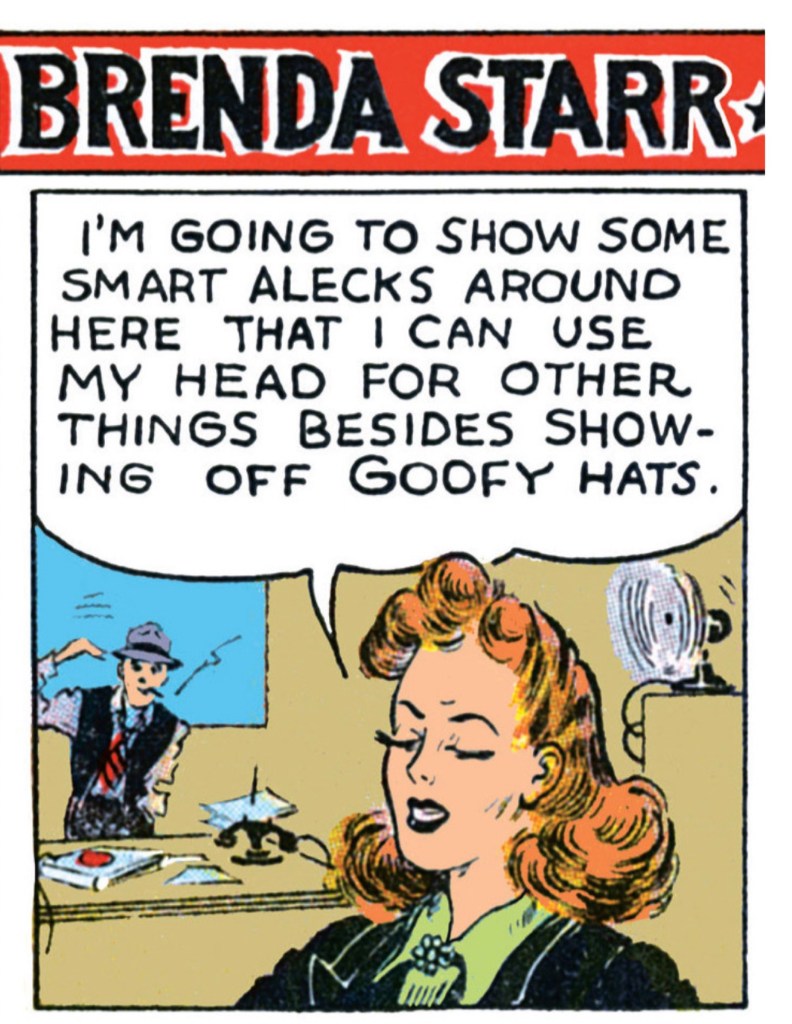

Like its eponymous heroine, Dale Messick’s Brenda Starr strip had to conquer the systemic sexism of the newsroom to make her mark. It launched in 1940 in constricted, Sunday-only syndication under the skeptical stewardship of New York Daily News legend Captain Joseph Patterson, after he had rejected Messick’s multiple submission for female-led adventure strips. According to lore, Patterson was unabashed in dismissing women in cartooning, claiming to have tried and failed with them in the past, “and wanted no more of them.” Messick’s samples were salvaged from the discard pile by Patterson’s more open minded assistant Mollie Slott, who helped the artist rework her ideas to feature an ambitious and dauntless female reporter. The artist was acutely aware of the gender deck stacked against her. Born “Dalia” Messick, she deliberately adopted the androgynous “Dale” to help get her strips considered more seriously. Slott convinced thge reluctant Patterson to give this red-headed firebrand and Rita Hayworth lookalike a try. History was made.

Continue readingMonthly Archives: June 2023

Jim Hardy: Forgotten Man

Dick Moores’ Jim Hardy (1936-42) crime adventure strip was more of an interesting curiosity than it was a success. Moores had done backgrounds and lettering for Chester Gould on Dick Tracy, and he achieved enduring fame later when he took over Gasoline Alley in 1959, a run that lasted until his passing in 1986. But Jim Hardy is an interesting freshman effort because of its attempt to move crime comics beyond his mentor’s wildly popular but narrow world view. In Jim Hardy, Moores was looking for a more rounded, richer crime fighter than Tracy.

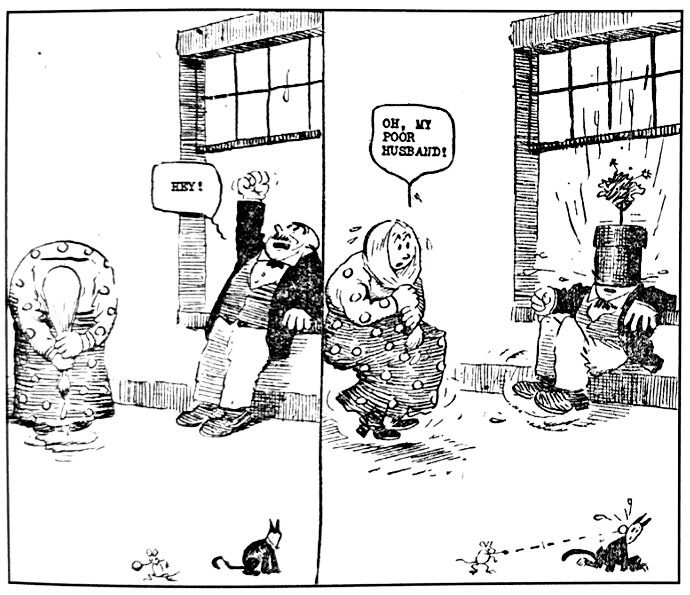

Continue readingInventing the Sitcom: The Dingbats Downstairs

The shrunken American male was always at the center of the modern family sitcom, and at the head of that long line of hapless hubbies is George Herriman’s pint-sized E. Pluribus Dingbat. The Dingbat Family premiered in June 1910, but was soon retitled The Family Upstairs when by the next month E. Pluribus had found his persistent nemesis, the noisy upstairs neighbors. When the strip is studied at all, it as the birthplace of Herriman’s more famous Krazy and Ignatz. Kat and mouse started as a secondary pantomime comedy at the bottom of the Dingbats, first seen on the same day the Dingbats discovered the irksome “family upstairs,” July 16, 1910 (see above). According to Herriman biogrpaher Michael Tisserand, the artist quickly fell in love with the Krazy and Ignatz dynamic, was able to spin the duo off into their own strip and make history. Herriman himself was unsure of the appeal of the Dingbats, even though his bosses at Hearst seemed to compel him to continue the series for six years. His heart belonged to Krazy. Still, in E Plurubus Dingbat Herriman was laying down some of the early tropes of the family sitcom. The diminished and dimuntive father figure had comic precedents, namely Jeff of Mutt and Jeff, Gus Mager’d Henpecko, and to a lesser extent the lesser half of George McManus’ The Newlyweds. But it is in The Dingbats that we start seeing the sitcom dad adopt his fuller cultural role. Haplessly raging against a modernizing world, bemoaning his own diminished authority, battling stylish children, neighbors, politicians, plumbers and garbagemen, half-baking schemes that always fail, much of sitcom fatherhood take shape in Pa Dingbat.

Continue readingRed Barry: Time for Your Close-Up

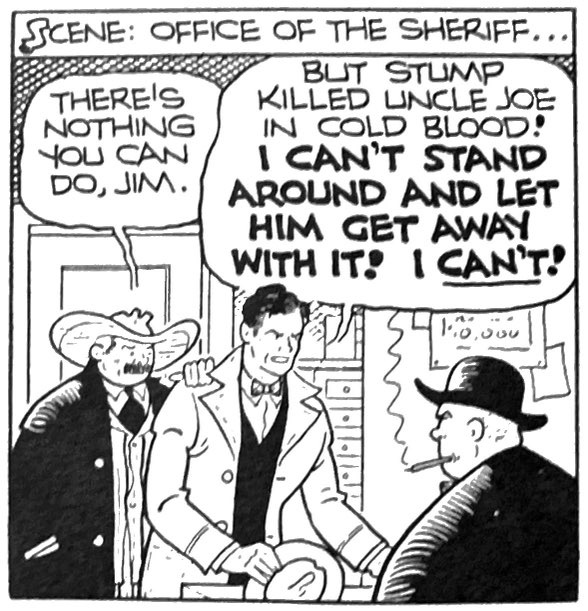

With a striking visual energy, speech and violence that was unlike anything else on the page, Will Gould ‘s (1911-1984) short-lived Red Barry (1934-38) jumped out of the Depression-era comics page. It was intended to mimic the success of crime comic powerhouse Dick Tracy. But the two unrelated Goulds, Tracy’s Chester and Barry’s Will, couldn’t have been more unalike in temperament and values. And so their visions of gangesterism, crime and heroism took wildly different paths. Red Barry was uniquely exciting among rival crime comics of the day, and even to the contemporary eye, it feels fresh. Everything vibrated with action and intrigue in the strip – from the modernist, machine age sharp edges to every person and thing in the panel to bolded words in speech balloons, to the massive, stylized shadows its characters cast on nearby walls. The strip blended cartoonish visual abstraction with realistic violence and plot lines that deliberately mimicked current news stories. In comparing it to Dick Tracy, Red Barry exemplifies how deeply and varied the personal visions and personalities of artists could inform a range of perspectives on society despite the institutional constrains of this mass medium.

Continue reading