With a striking visual energy, speech and violence that was unlike anything else on the page, Will Gould ‘s (1911-1984) short-lived Red Barry (1934-38) jumped out of the Depression-era comics page. It was intended to mimic the success of crime comic powerhouse Dick Tracy. But the two unrelated Goulds, Tracy’s Chester and Barry’s Will, couldn’t have been more unalike in temperament and values. And so their visions of gangesterism, crime and heroism took wildly different paths. Red Barry was uniquely exciting among rival crime comics of the day, and even to the contemporary eye, it feels fresh. Everything vibrated with action and intrigue in the strip – from the modernist, machine age sharp edges to every person and thing in the panel to bolded words in speech balloons, to the massive, stylized shadows its characters cast on nearby walls. The strip blended cartoonish visual abstraction with realistic violence and plot lines that deliberately mimicked current news stories. In comparing it to Dick Tracy, Red Barry exemplifies how deeply and varied the personal visions and personalities of artists could inform a range of perspectives on society despite the institutional constrains of this mass medium.

In 1933, Gould was among the many newspaper artists who vied to draw King Features’ plan to compete with Dick Tracy’s success by throwing at it the legendary crime novelist Dashiell Hammett. Hoping that King and its President Joseph V. Connolly would ride the crime comics wave with more than one entry, Gould also submitted spec strips for Red. Drawing from his own acquaintance with prosecutors, seedy characters and crime coverage, Gould imagined Barry as a former football star turned undercover cop who penetrated gangland.

In a melodramatic denouement straight out of a crime pulp itself, Gould recounts being called to Connolly’s office where he also met Hammett and rising star artist Alex Raymond. Connolly announced he was pairing Hammett with Raymond to work on what would become Secret Agent X-9 but letting Gould proceed with Red Barry as well.

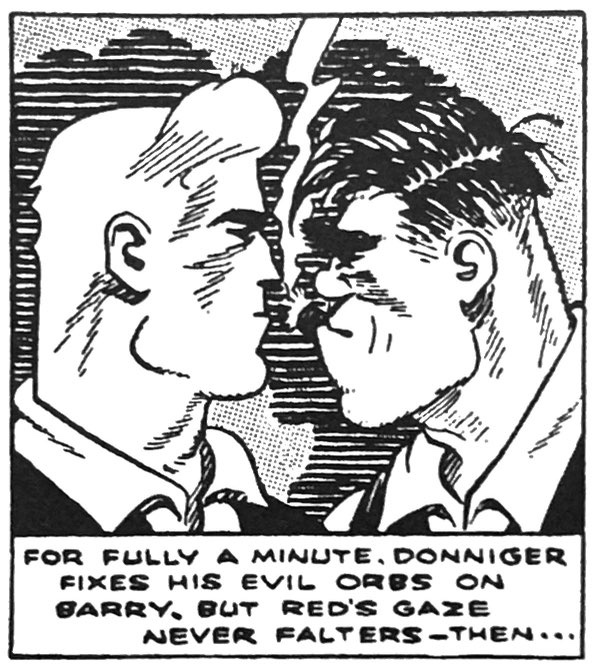

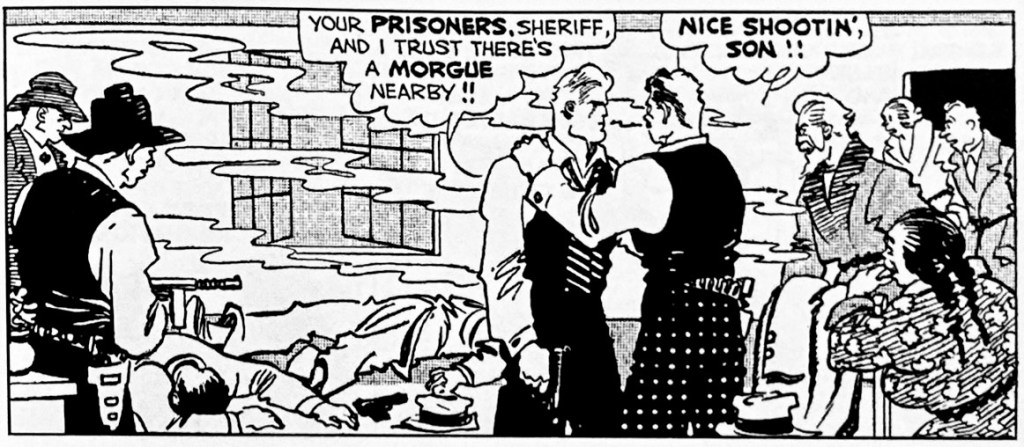

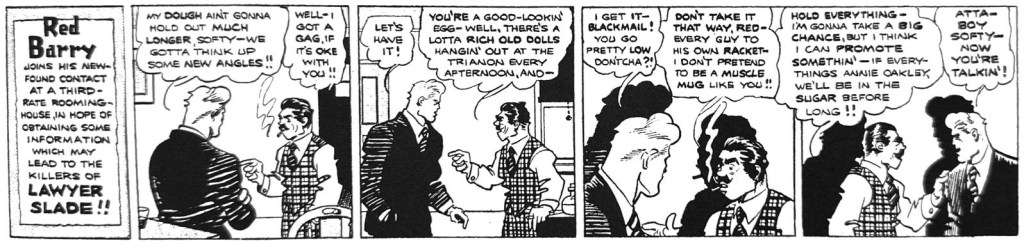

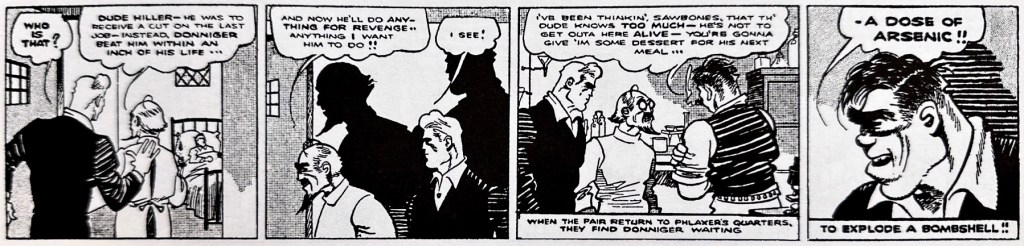

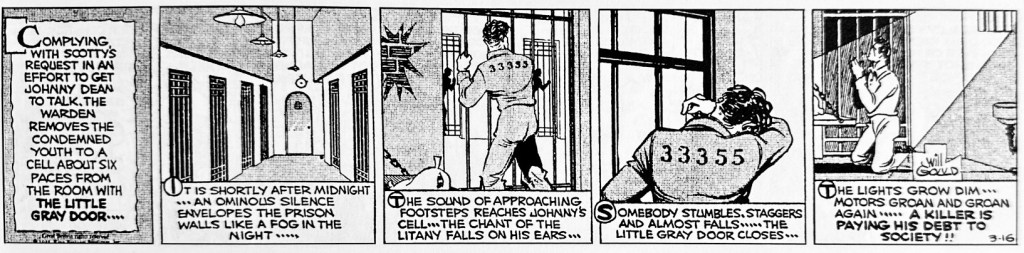

Gould’s stunning deco visual style feels like it was peeled off the side of Rockefeller Center. The thick, sharp-angled outlines give Red, his boss Scotty and most of the villains the look of chiseled stone or abstract woodcuts. The power of Gould’s visual voice is all about mass. Red’s masculine heroism is embodied in the handful of bold lines and curvy hairlines that craft a massive head and bovine neck. Red shares with Dick the steadfast hawk nose and square jaw, but Will Gould’s swathes of chiaroscuro shading and abstract minimalism lends Red a more mythical warrior look that seems to have popped off Mount Rushmore. Years before film noir, Will’s characters were casting enormous shadows that were often filled variably by odd outlines or thick parallel lines. They effected a range of tones, from menace to secrecy, intimacy to introspection. It both reached back to the German Expressionists of the 20s and anticipated the language of American Noir. Both Tracy and Barry were highly stylized and expressionist. But while Chester was fond of deep perspective and engaging foreground and background in entertaining ways, Will liked to fill his panel with his faces, amplifying their conflict or conspiracy with a palpable emotional tension and force that was not in Dick Tracy’s palette.

Red Barry’s plots and cast of characters were often crowded and twisted. Operating under deep cover, Red’s true identity and purpose were known mainly to Inspector Scott (Scotty) and an improbably vast, widening network of friends and helpers. He had his own Junior Tracy in the orphaned Ouchy Mugouchy, who would dominate the final year of the strip with his boy gang of crimefighters, The Terrible Three.

Red Barry separated itself from a growing field of 1930s crime comics, which included X-9, Radio Patrol (also from King), Dan Dunn, Jim Hardy and many lessers. Most of all, Gould truly crafted an immersive underworld feel to the strip. This strip was less about crime than it was about a culture of crime. The stories themselves deliberately echoed headline news, from gang wars and blackmail rings to innocent bystanders caught in criminal crossfire. One of his preening, self-important gangsters, Bull Donninger was a thinly veiled iteration of celebrity thug John Dillinger. Many of the plots involve multiple city gangs where their rivalries and internal power politics become part of the central mystery.

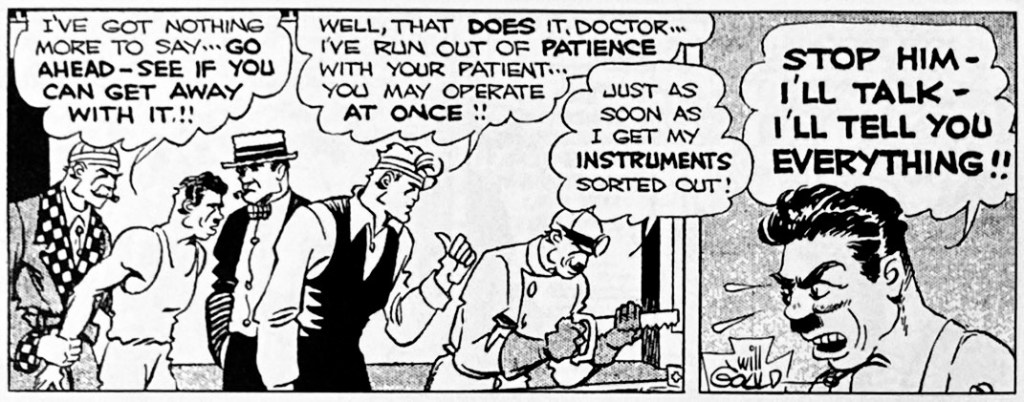

But the plots themselves were truly labyrinthine and often outlandish. Gould’s stories could go on for months and veer into unlikely side-plots, mini-schemes, weird set-ups and ego-driven rivalries among masterminds. A criminal doctor performs plastic surgery on himself and another to fool police by duplicating himself. Red and Scotty terrify a henchman into ratting on his friends by staging a mock operation without anesthetic. A gang kidnaps the state governor to ensure that the many they framed for a crime is duly executed. Informants and double-crossers seem to be everywhere. Deceptions, disguises, and an incredible body count pave our way to the villain’s final capture.

Oddly, for all of its improbabilities, Red Barry felt more genuinely underworldly than any other crime comic. While Red and Scotty represented fidelity to law and order, the taint of corruption, criminality, self-serving politics seemed to be everywhere. This strip felt more brutal and unflinching than any other strip in depicting an underworld that was hardly under wraps or under restraint. And by making his hero an undercover spy, Gould ensured that we spent as much time in gangland as we did in police precincts.

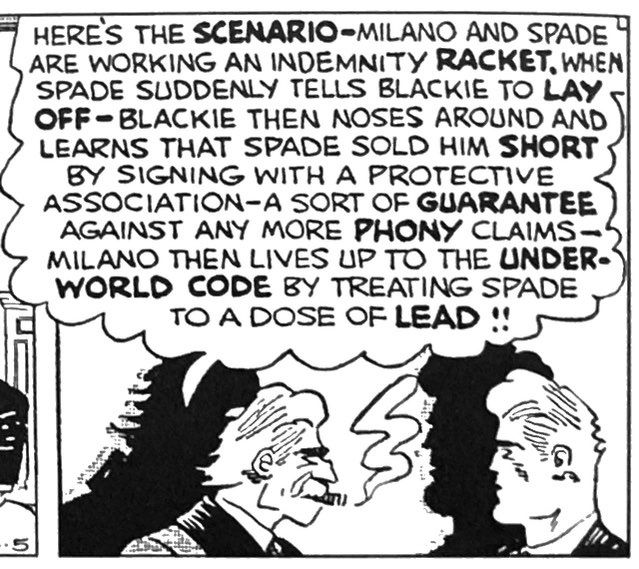

Comics historians like to cite Gould as one of the innovators in lettering, as he used bolded words to give his speech balloons a special emphasis and cadence. It was one of the ways that the comics medium could distinguish itself from text-bound media, by blending the visual and the verbal to unique aesthetic effect. As important to the tone of the strip was the language itself. Gould’s characters exchanged hard-boiled lingo with the velocity of machine gun fire. Hammett’s Continental Op and the patois of 30s gangster films couldn’t hold a candle to Gould’s dialogue, which was a lexicon of relentless figurative references and urban criminal metaphors. Some of the tough guy lingo is familiar – guns = “heaters” etc. But professional boxers (“pugs” don’t box but “push leather.” People don’t see one another so much as “lamp” them. Pickpockets are “Poke-lifters.” Priests are “sky pilots.” iAnd again, the dialogue of Red Barry imagined a true culture of crime with its own language that preferred talking in colorful codes.

It at times Red Barry approached burlesque, that was part of the strip’s unique charm and world view. Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy villains were genuine grotesques, irredeemable evil-doers who eventual demise was deserved and necessary. Will Gould’s underworld is highly performative, filled with showy, tough-talkers always trying to project their hardness to maintain power.

Which is to say that Gould brought to the Red Barry strip a psychological approach to character that was much closer to Milton Caniff in Terry and the Pirates or Tuthill’s The Bungle Family than it was to other crime comics. The egotism of the tough guy and its underlying insecurity is embedded in the banter and the action. Gangsters aren’t just beaten; they are humiliated or in some way emasculated. One of Gould’s early celebrity baddies, Donninger, is a headline-hungry, vainglorious poser, personality flaws that Red uses to his advantage. A more pulpish super-villain “The Montk” is a mastermind who is literally diagnosed by a handwriting expert as a “dangerous ego-maniac with a Rasputin complex.” Chester Gould’s grotesque villains usually stand outside humanity both physically and morally. Will Gould’s vision of criminality is usually a warped extension of humanness.

Gould’s psychological sensitivity led to genuine pathos. Following the template of American male heroism, Red’s masculine bravado has a purpose, staring down (sometimes literally) the ego-driven gangsters. But unlike the villain, his violence is principled and tempered by sentimentality that seems to balance, even justify his love of force. His paternal devotion and love for his virtual son Ouchy is worn on his sleeve. And Gould himself showed a fair emotional range. One of the most aesthetically and dramatic sequences in the strip’s short history brought us into the heart-rending torture of the prison death house. Racing against the doom clock of a wrongful execution, Gould spends weeks depicting the final hours of a prisoner’s impending death. Gould is at the height of his graphic power here. The taunts of fellow inmates, the looming, ever-present door to the electric chair, the pain of watching others march to their doom – are rendered in excruciating detail.

It is worth comparing Red Barry and its artist to its obvious progenitors, Dick Tracy and Chester Gould. The two artists couldn’t have been more unalike. Chester was a famously no-nonsense and pious workaholic. His vision of villainy, evil, criminality was cut and dried. His world was unambiguous, devoid of psychological nuance. While law and order institutions were sometimes pompous and a bit hapless, their righteousness was assumed. Dick himself could show an extra-legal, vigilante style on occasion, but this always served a clear higher good. His story lines could get outlandish (especially involving Tracy’s death-defying escapes) and laden with coincidence. But they were rarely complicated or even very mysterious. They rarely involved emotional depth, exotic twists, let alone introspection. Artistically, Chester was famously expressive and individualistic, however. His sense of design, composition, deep perspective were so engaging. His art was at once very literal and abstract.

Will Gould was temperamentally the opposite. As his assistant Walter Frehm recalled, only eleventh-hour deadlines could pull Gould off the golf course or out of the Hollywood Brown Derby nightclub to do 48-hour crunch sessions at the drawing board. As time went on the art looked as rushed as it was. Frehm followed Gould to the golf course and out clubbing, notebook in hand to record the story lines that were cooked up on the fly. But this anti-Gould artist also created a worldview that was just as different from Dick Tracy and most other crime comics as one could imagine. It had whimsy, depth, a genuine vision of 30s era underworlds and their connection to everyday America. He was even a bit churlish. As if to compare his own strip and his hero to the range of other mystery and crime fiction of the thirties, he lampooned the effete detective Philo Vance, S.S. Van Dine’s amateur detective of novels and film. The ever clueless Police Commissioner Trent keeps the “society sleuth Valentine Vane” busy pursuing parallel, usually fruitless, investigations of the crimes Red eventually solves with his two-fisted, hard-boiled undercover approach. Like Dashiell Hammett, Gould was self-consciously rejecting the polite, cozy mystery whodunnit mystery genre that Van Dine and others imported from British pop lit. More deliberately certainly than Chester Gould, Will Gould was asserting an american, hard-boiled approach to crime writing.

Alas, Red Barry remains more of a sidebar in media history, if only because Gould’s own poor discipline led to chronic blown deadlines and ill will between artist and syndicate. A contract dispute ended their relationship and Red Barry in 1938. Gould went on to scriptwriting for TV and radio.

Red Barry Has never been reprinted in its entirety. The Library of American Comics (IDW) is a beautiful edition covering the first year of dailies and Sundays, but LOAC elected not to continue the reprint. An earlier, poorer B&W rendition of 4 Sunday episodes from 1934-37 was done by Fantagraphics in 1989.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.