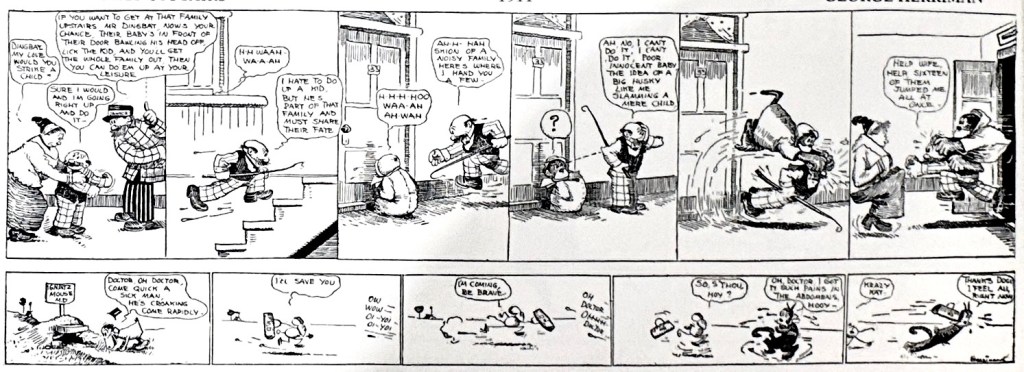

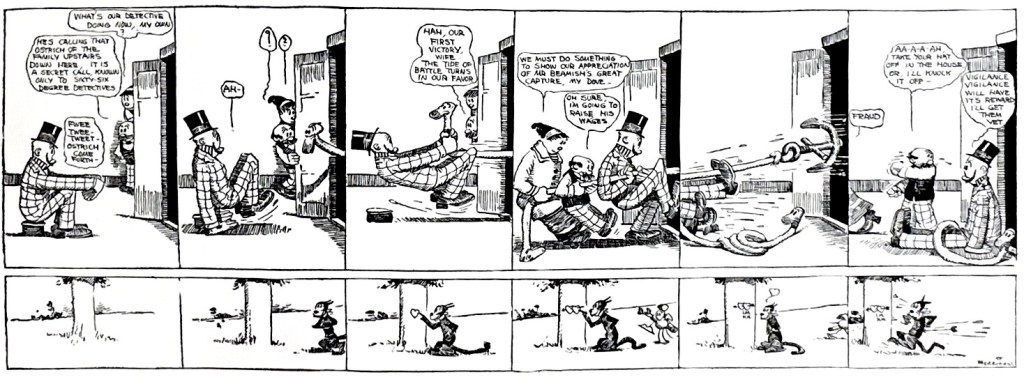

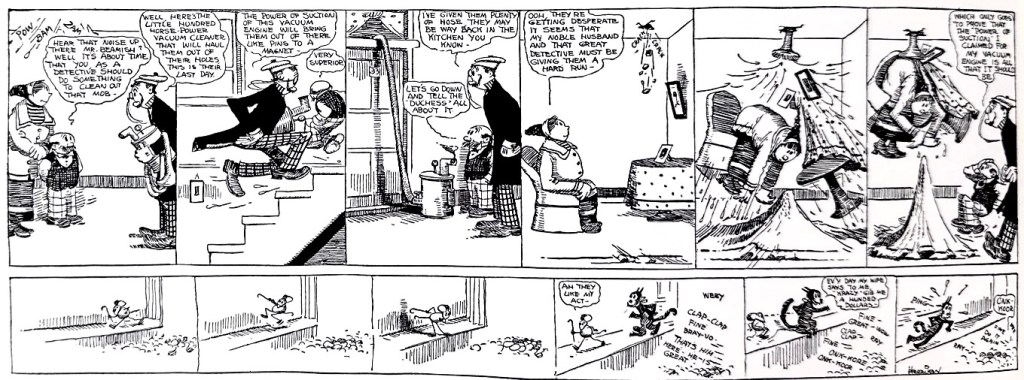

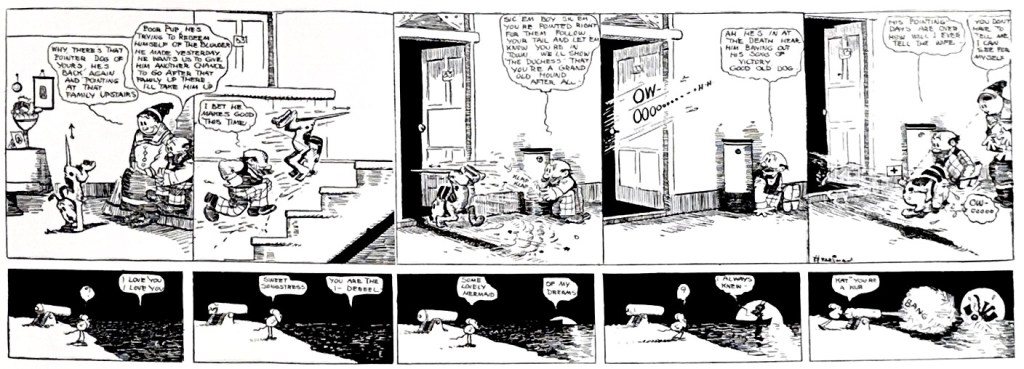

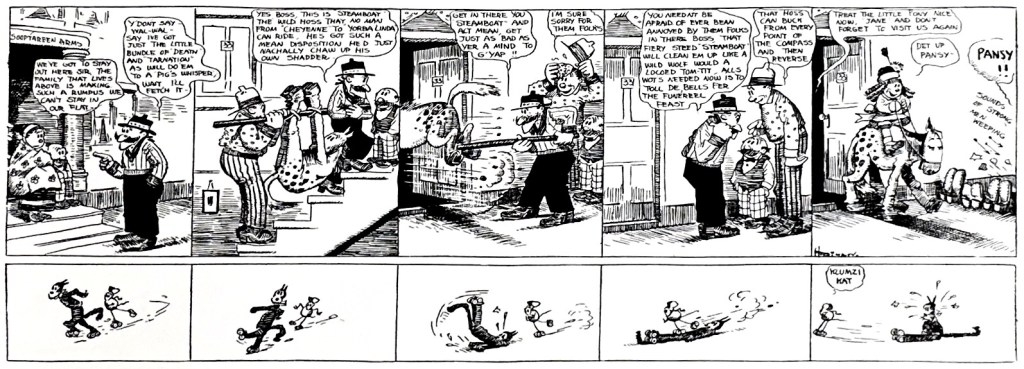

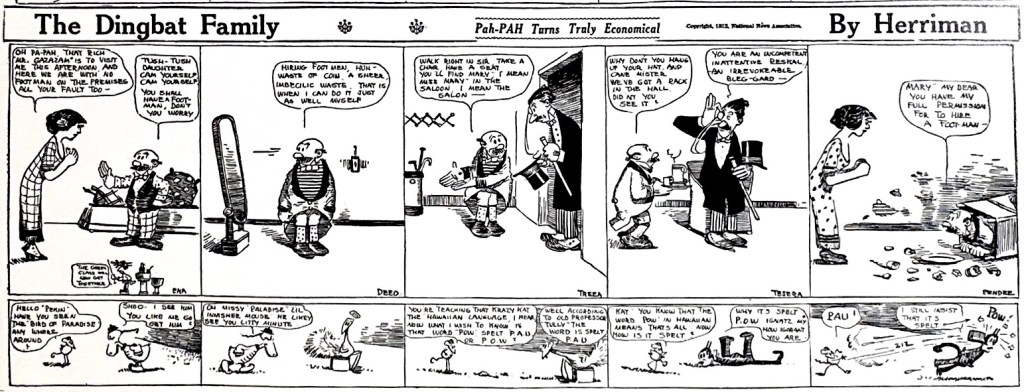

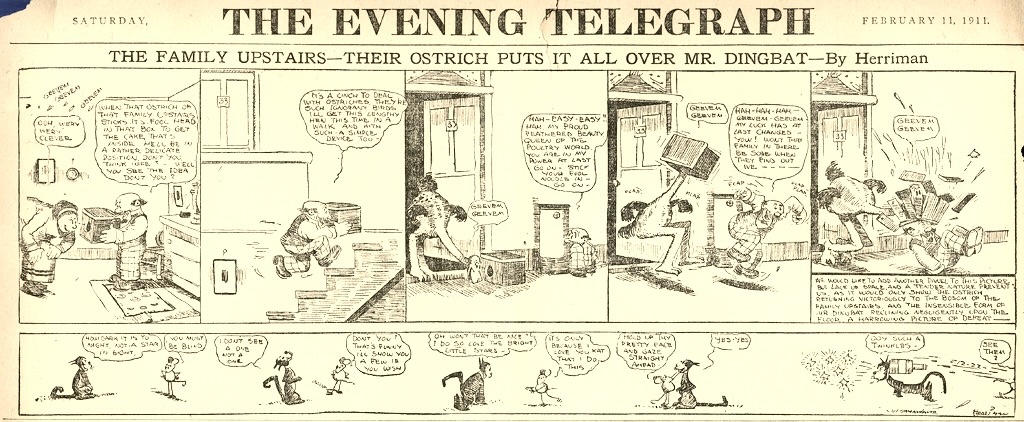

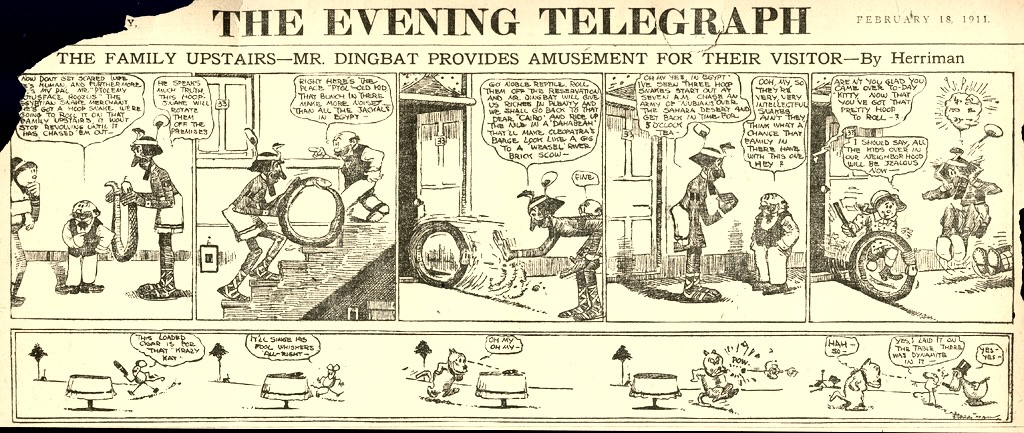

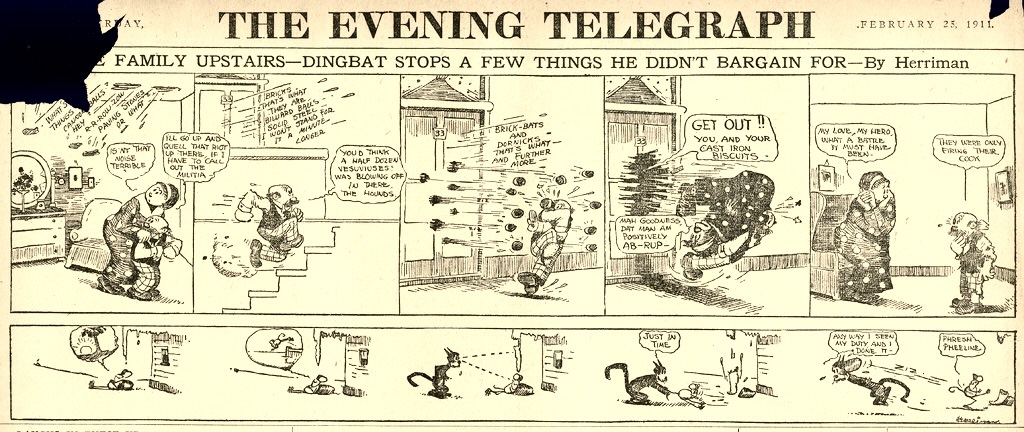

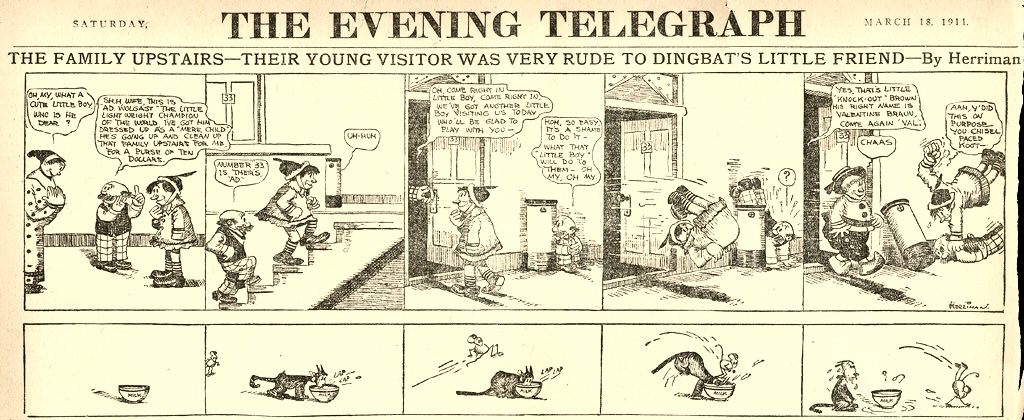

The shrunken American male was always at the center of the modern family sitcom, and at the head of that long line of hapless hubbies is George Herriman’s pint-sized E. Pluribus Dingbat. The Dingbat Family premiered in June 1910, but was soon retitled The Family Upstairs when by the next month E. Pluribus had found his persistent nemesis, the noisy upstairs neighbors. When the strip is studied at all, it as the birthplace of Herriman’s more famous Krazy and Ignatz. Kat and mouse started as a secondary pantomime comedy at the bottom of the Dingbats, first seen on the same day the Dingbats discovered the irksome “family upstairs,” July 16, 1910 (see above). According to Herriman biogrpaher Michael Tisserand, the artist quickly fell in love with the Krazy and Ignatz dynamic, was able to spin the duo off into their own strip and make history. Herriman himself was unsure of the appeal of the Dingbats, even though his bosses at Hearst seemed to compel him to continue the series for six years. His heart belonged to Krazy. Still, in E Plurubus Dingbat Herriman was laying down some of the early tropes of the family sitcom. The diminished and dimuntive father figure had comic precedents, namely Jeff of Mutt and Jeff, Gus Mager’d Henpecko, and to a lesser extent the lesser half of George McManus’ The Newlyweds. But it is in The Dingbats that we start seeing the sitcom dad adopt his fuller cultural role. Haplessly raging against a modernizing world, bemoaning his own diminished authority, battling stylish children, neighbors, politicians, plumbers and garbagemen, half-baking schemes that always fail, much of sitcom fatherhood take shape in Pa Dingbat.

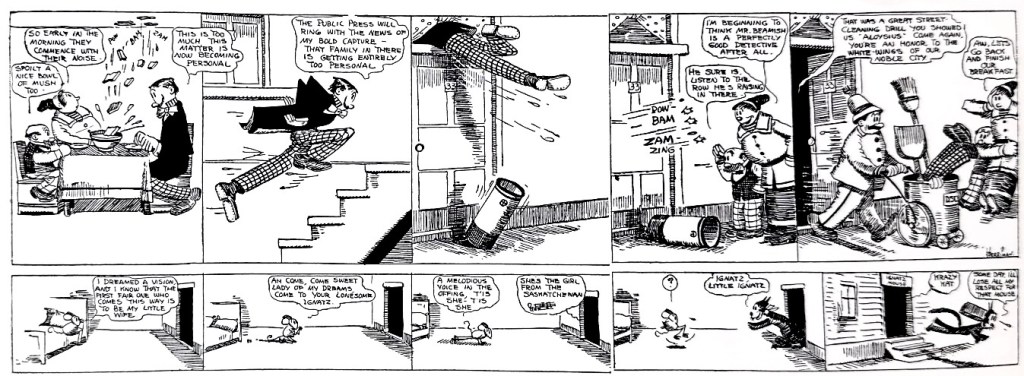

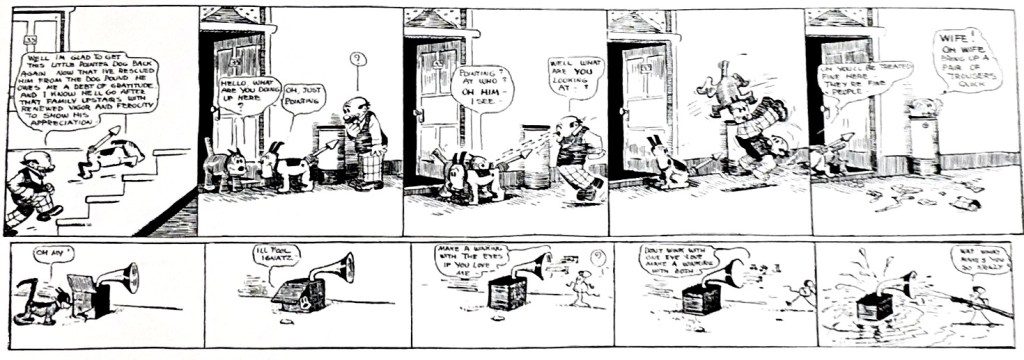

Like countless comic dads after him, Mr. Dingbat is fully half the size of his wife and family and almost everyone else in the world. His frustrated attempts to assert his will on the world is made to seem comically fruitless by his actual stature. It is a device that Cliff Sterrett refined in Paw and his brilliant Polly and Her Pals in 1912. I have already gone on at length about the basic components of the family sitcom as they matured in Polly, The Nebbs and Bungles. But it is worth spending some time on the rarely reprinted Dingbats to consider how as early as 1910 we are seeing the satirical takes on the nuclear family start taking shape even as that modern American urban and suburban social structure is taking hold.

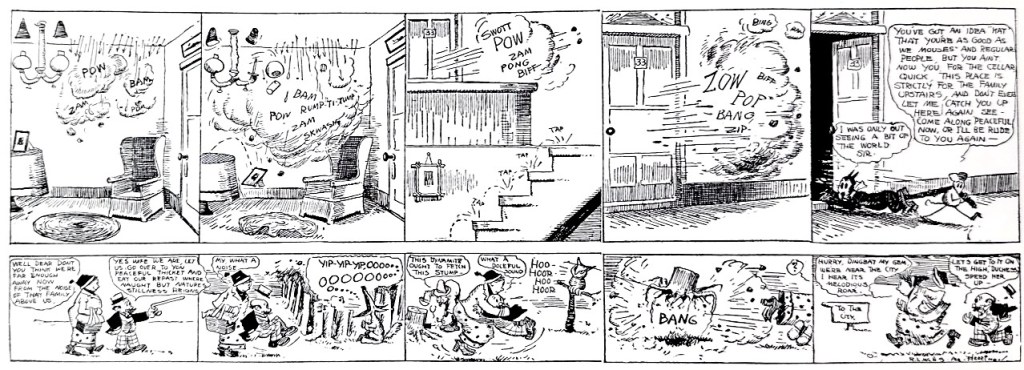

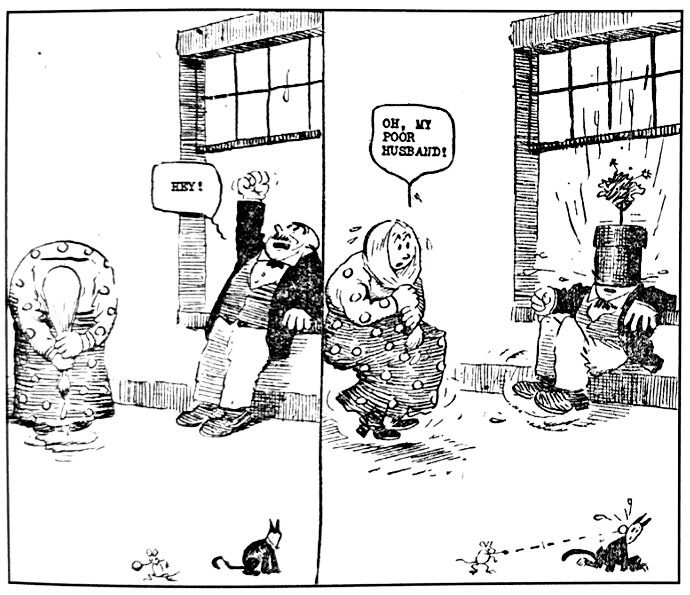

E. Pluribus is singularly obsessed with defeating his loud but invisible neighbors. Male bravado, certainty of his own cleverness (despite relentless failure), extravagant schemes, the patronizing support of his clearly more sensible wife, are all satirical threads that defined the genre for the next century. The same dynamic courses through Chester Riley, Ralph Kramden, Homer Simpson.

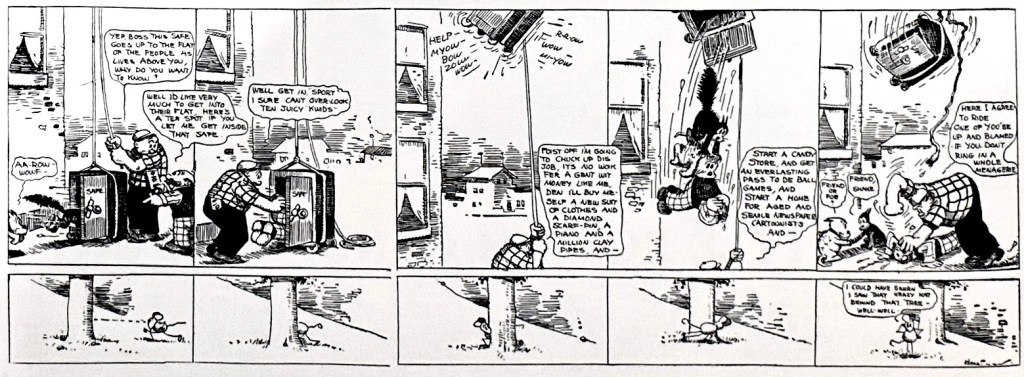

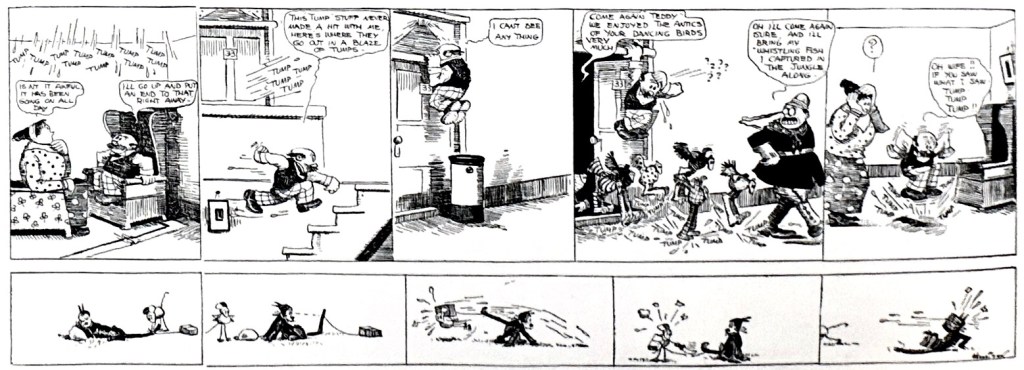

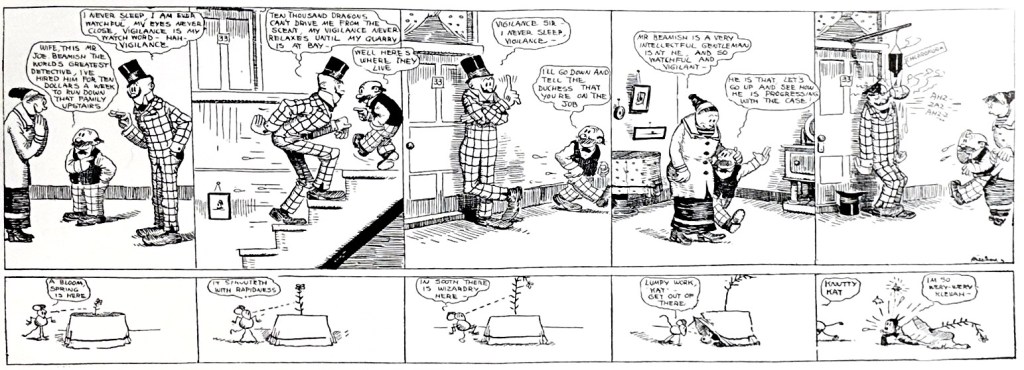

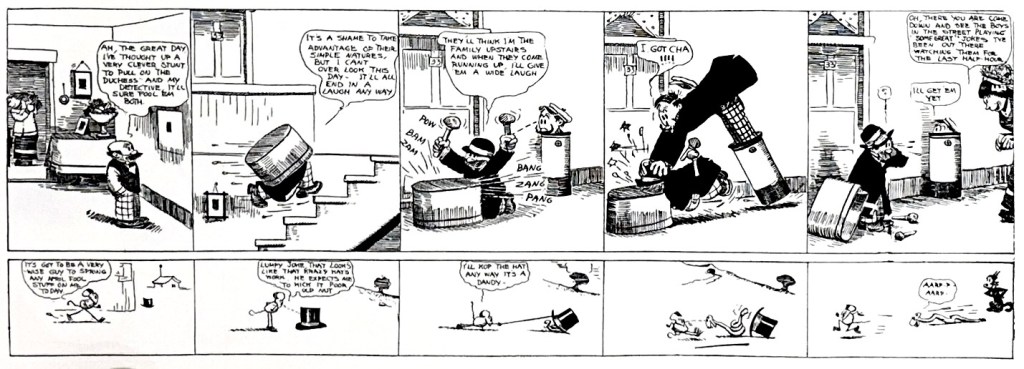

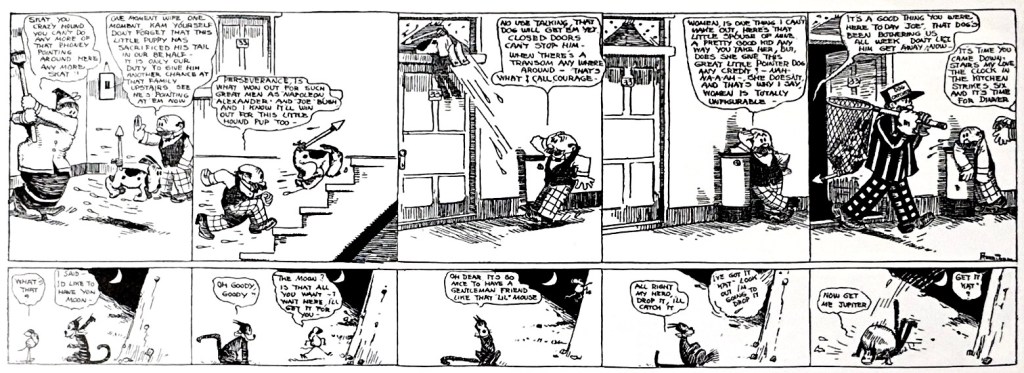

Herriman’s native absurdism brought his Dingbats into realms unexplored by most subsequent sitcoms, however. E. Pluribus goes to wildly unlikely lengths to bring down his neighbors. He recruits the world’s most famous detective, who in turn recruits troops from the Russian Czar. He hides himself in a safe, tries to use magnetic devices, a pointing pup, a wild horse. He employs a mystic to deploy “hoop snakes.” And the mysterious family upstairs are themselves superheroic antagonists. We never see the family itself but witness a parade of associates, from Teddy Roosevelt to friends, garbagemen, talented monkeys, all of whom easily defeat E. Pluribus’s schemes. There is an absurdist universe, an epic battle of worlds Herriman contains in two floors of a city walk-up. In many ways, The Dingbats was the inverse of Herriman’s eventual masterpiece Krazy Kat. Coconino Country and the ever-changing vistas of Herriman’s beloved southwest was an infinite setting for contemplative, even metaphysical themes. The Dingbats contains worlds of action and characters in two flats and a staircase.

On occasion, Herriman enjoyed inverting Krazy and Ignatz’s bottom tier with the Dingbats above.

While he didn’t dwell on the domestic comedy tropes that Sterret, McManus and Sydney Smith would make central tot he sitcom, Herriman foreshadowed some of them. Like decades of sitcom children, the younger Dingbats aspire beyond their station, which prompt familiar gags around social class, schemes to deceive. In the strip below Pa poses as a footman to help his daughter impress a snooty suitor.

The domestic situation comedy genre would soon blossom with Sterrett’s Polly and Her Pals (b. 1912), McManus’ Bringing Up Father (b. 1913), and particularly the massively popular The Gumps (b. 1917) by Sydney Smith. The sitcom has become so baked into modern mass media genres that it is easy to miss that it is a discrete genre that germinated in an importantAmerican moment. In part, the genre served the economic aims of the newspaper industry. As newspapers and then comic strip syndicates served a nationwide audience outside of major metros, publishers actively targeted content that mirrored a more suburban/rural and middle class audience. According to a 1928 newspaper industry report, the number of subscriptions grew from about 31 million in 1880 to 232 million in 1923. The newspaper was the first mass medium of the 20th century that rapidly penetrated everyday life. And after 1912, when Hearst first collected multiple strips onto a single daily page, the comics became the first powerful everyday art form in the American home. Not surprisingly, the comics then took both everyday manners, morals and foibles of that American home as its central concern.

And it is that everyday, often trivial commonness of the domestic strip that obscures its subtle cultural role. Consider that the domestic sitcom is a persistent, gentle satire that subverts many of the self aggrandizing tropes of other mass media. Competence, virility, physical power, masculine prowess and resourcefulness form the core of mass entertainment, the heroic fictions with which modern America has celebrated its idealized self. In radio, film and TV, the sitcom often turned in a similar self-aggrandizing direction. Andy Hardy, Father Knows Best, Leave It to Beaver, The Cosby Show, et. al. restore the sitcom father to wise authority and disarm any satiric possibilities by redirecting comedy from the foppish father to the socialization comedy around children. The saccharine sitcom of post-WWII TV was always aimed at ratifying normality. But in the American comic strip through much of that same century, dads remained delightfully emasculated, ridiculously overconfident. easily controlled by savvier wives, and incompetent. More often than not, the strip was a relentless satire of the modern master narrative. What role does such. an enduring counterpoint to America’s self-view have on our culture? I’m not sure. But the tradition is there and worth taking seriously as a part of the modern cultural fabric.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: The Democratic Genius of Clare Briggs – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Charles Dana Gibson Educates Mr. Pipp – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Flesh, Fantasy, Fetish: 1930s and the Return of the Repressed – Panels & Prose