Dick Moores’ Jim Hardy (1936-42) crime adventure strip was more of an interesting curiosity than it was a success. Moores had done backgrounds and lettering for Chester Gould on Dick Tracy, and he achieved enduring fame later when he took over Gasoline Alley in 1959, a run that lasted until his passing in 1986. But Jim Hardy is an interesting freshman effort because of its attempt to move crime comics beyond his mentor’s wildly popular but narrow world view. In Jim Hardy, Moores was looking for a more rounded, richer crime fighter than Tracy.

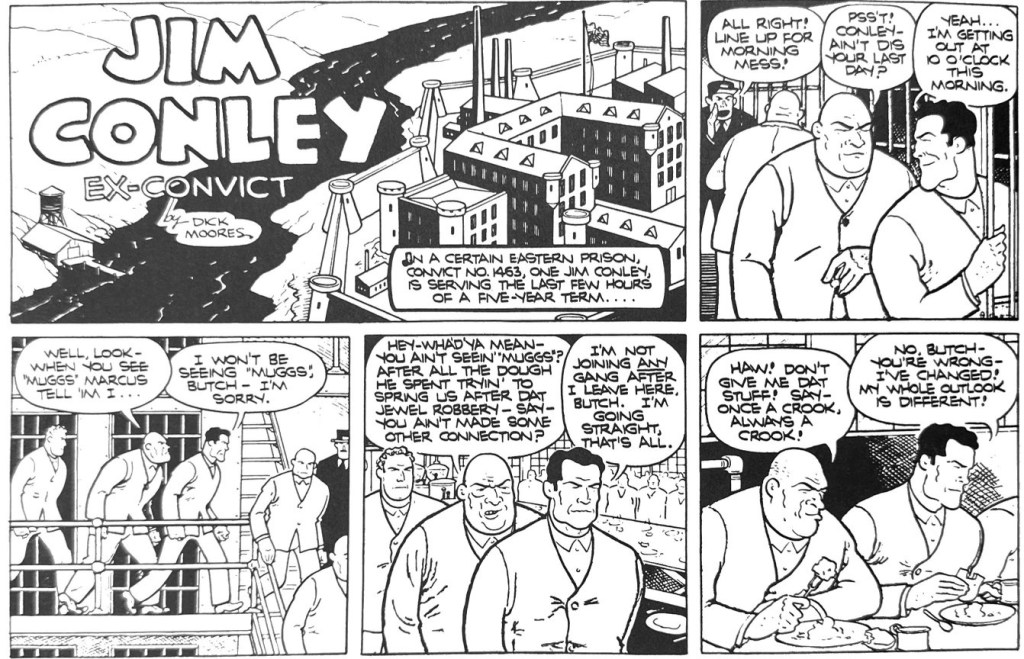

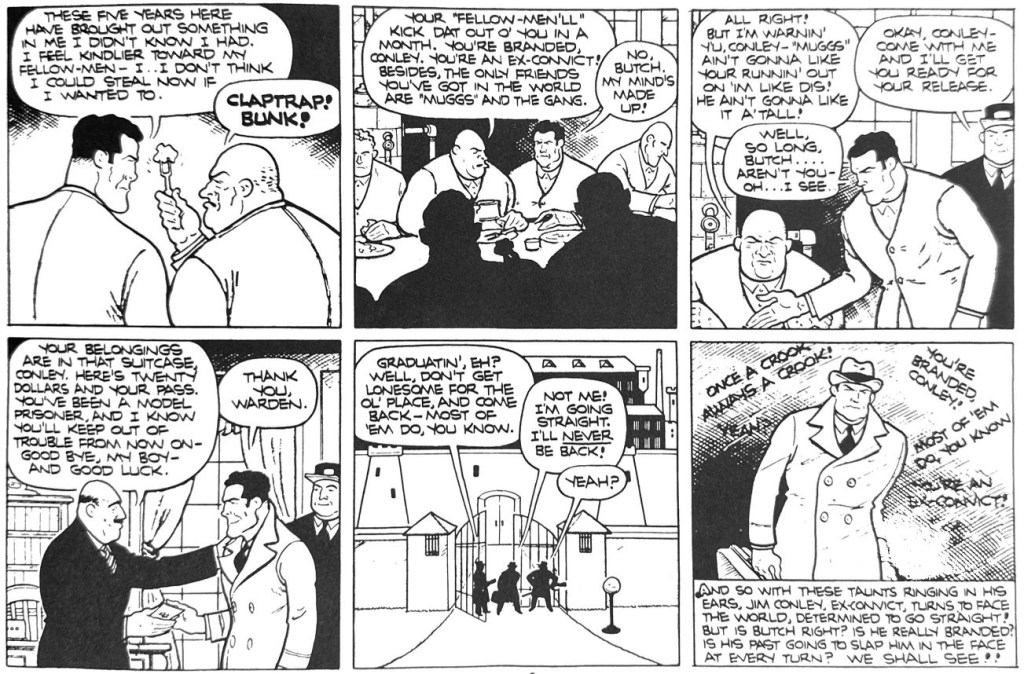

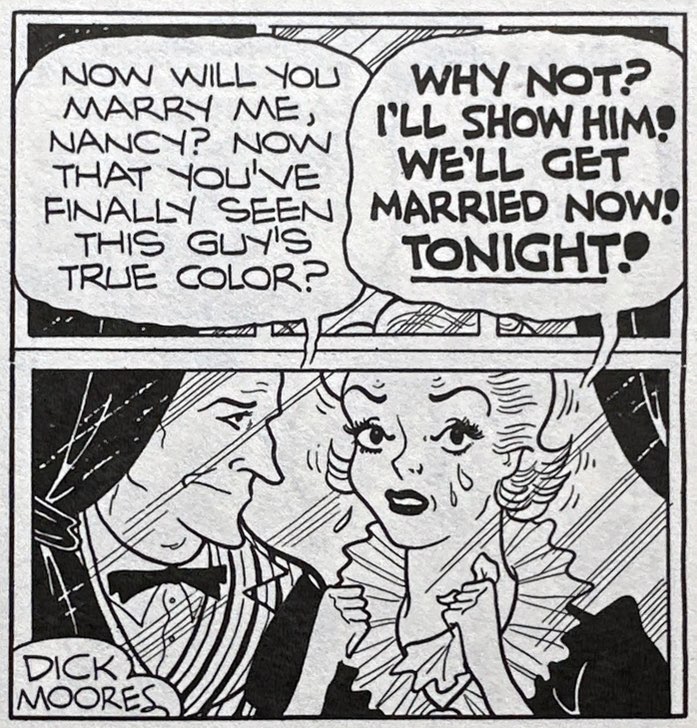

Moores had been struggling for years to move out of Gould’s shadow with a strip of his own. United Features finally took up one of his many proposals, a hard-boiled tale of ex-convict Jim Conley who was trying to break from his own gangster past. Newspapers rejected the idea of an heroic ex-con, so Moores and the syndicate retooled the strip as Jim Hardy: Man Against the World. In this reimagining, Jim is down on his luck when an old friend-turned gangster tries to lure him into a life of crime. In the process, Jim is mistaken by authorities as a gang member but ultimately proves his heroism by infiltrating and thwarting the criminal mastermind’s plans. By Moores’ own admission, the problem with Jim Hardy was that his author never decided who he wanted his hero to be. He journeys through various careers and settings, but usually lands as a reporter who worked in parallel and in tandem with the law to unwind a range of villains.

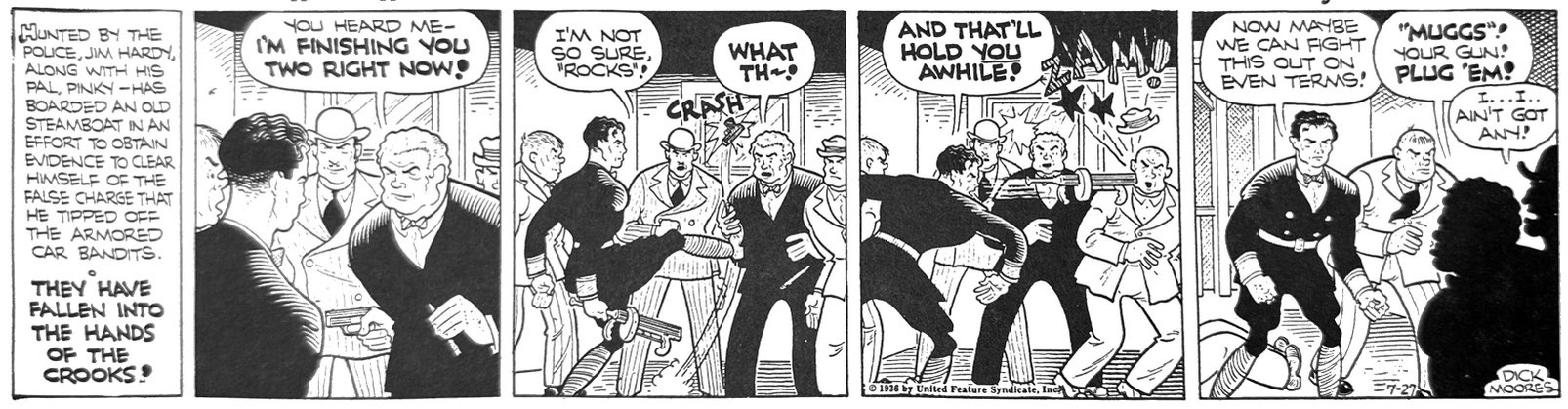

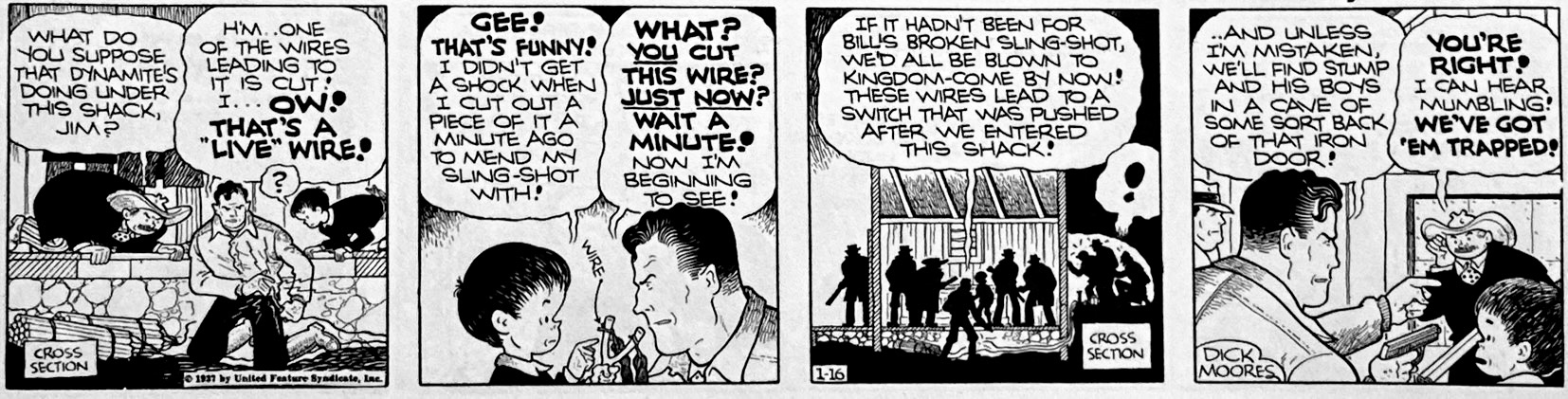

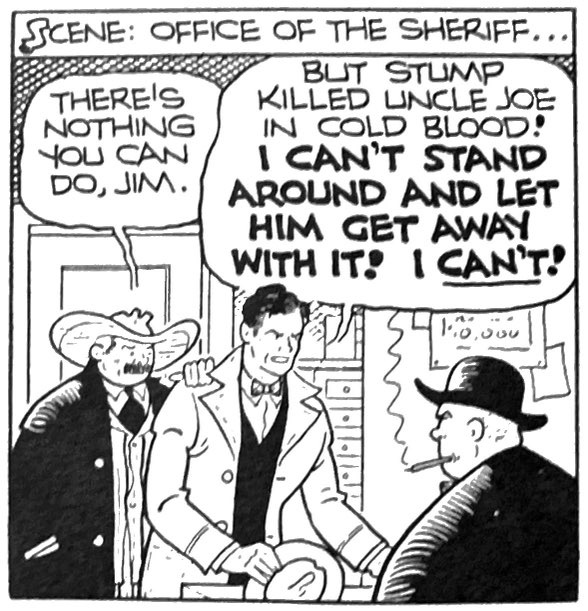

And yet the strip remains interesting precisely because we are watching a young comic artist wrestle with his own skills and narrative purpose. In style and story, Jim Hardy feels like a kinder, gentler Dick Tracy. After his initial gangersterland adventure, Jim is called west (literally…to “Westburg”) to save his Uncle Joe’s small town newspaper. Much like Tracy, who is activated by the shooting of Tess’s father in a holdup, Jim is energized to crime fighting when Uncle Joe is shot and killed by the con man Stump, who is trying to swindle Westburg citizens with a factory investment scam. In the ensuing chase through the Western hills, Jim gets his “Junior” as well, when he frees the orphan Bill from an abusive band of desperados. And there is a Tess, too: hometown sweetheart Nancy Snow.

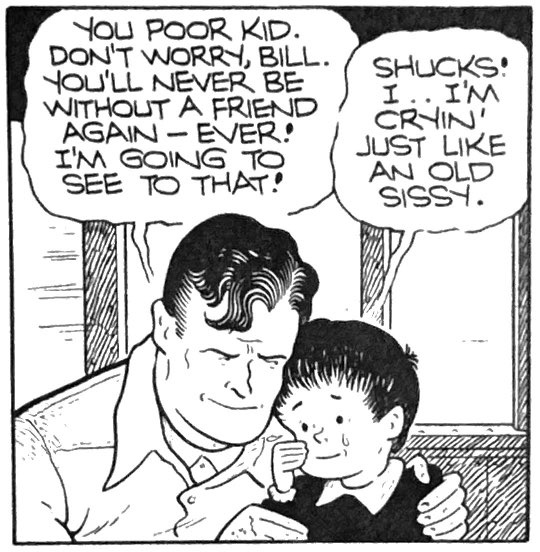

Unlike Chester Gould’s steadfast and stoic Dick, Moore endowed Jim and the strip with considerably more sentiment and even psychological dimension. This is a hero with a lot of heart. His devotion to the young Bill is closer to the surface. Hugging is allowed here. Likewise his courting of Nancy is genuinely romantic and itself becomes a lengthy storyline involving intrigue, rivalries, tearful moments (even from our hero) and more than a little kissing. Hardy was righteous, to be sure. But Moores was breaking free from the stoic, unforgiving moralism of Gould’s world view. The strip is as sentimental as it is action-packed. Jim is a two-fisted he-man in the crime fighter mold, but he also experiences self-doubt, genuine heartbreak, and moral uncertainty. In one of Moore’s best attempts to visualize his hero’s inner turmoil, the introspective Jim is followed by a ghost-like conscience that embodies his two minds. And while Moores later criticized the strip’s lack of focus, Jim’s nomadic, journeyman existence surely channeled the American ethos of the 1930s. Persistently dislocated, looking for his place and a path up from hard luck but righteous and strong, Jim embodied qualities FDR may hav had in mind in referring to the “Forgotten Man” his New Deal was designed to help.

Jim Hardy is most engaging visually, sitting somewhere between Gould’s surreal expressionism and Zack Mosley’s lighter cartoonish adventure style in Smilin’ Jack. He adopts what Ron Goulart has characterized as the “Chicago” style, “that bold, flat poster-like approach favored by Gould, Harold Gray, Sidney Smith.” His objects and settings were iconic. Guns, lamps, trees and mountains had a generic symbolic look. In repose and in action, his human figures had a marionette-like stiffness that owed much to Gould. Much like Dick, Jim’s figure is defined visually by a big swathe of black suit that dominates any frame against the outlined secondary characters. Moores even adopted Gould’s explicit object labels and cross-section explainer views to illustrate sequences in clinical detail. And he made liberal use of silhouettes to lend visual variety to a scene. But at the same time, Moores was starting to flex his own muscular style. He liked to crowd his panels with multiple characters in tight shots to dramatize emotional tension that looked more like Will Gould’s Red Barry and Mosley’s Smilin’ Jack. And overall, he had a lighter, rounded approach that was less stark and geometric than Chester Gould’s. His early villain, the swindler Stump, is a fine example of him playing with cartoon evil. The lanky and tall con man has a massive bulbous head, thinning slicked hair and a bizarre jutting nose that looks like a crone’s crooked finger.

Ultimately, Jim Hardy fails because Moores’ himself didn’t seem that interested in the crime adventure genre. He had no clear vision of what crime was. Chester Gould had a firm sense of metaphysical evil to animate his strip. Will Gould’s Red Barry had its own grasp on a complex, inevitable urban underworld. Even the more procedural Radio Patrol drew from its journalist authors’ familiarity with tales of criminal greed and corruption. Moores was so loosely attached to the crime genre that Jim Hardy eventually morphed into a strip about a cowboy named Windy and the racehorse Paddles, for whom the strip was retitled before its demise in 1942.

Moores was clearly searching in Jim Hardy, for a style of his own as well as a character and firm career path for Jim. His storylines were often improbable and sprawling, feeling even more improvisational than Gould’s. The story that begins with Stump’s big swindle of Westburg becomes a chase that brings him into the snowy tundra, a criminal enclave, a ghost town, back to Westburg and a lengthy romantic misadventure, a false marriage for Nancy and multiple near-death escapes. And throughout Moores tosses in a massive cast of sharp and feckless lawmen, robbers, conniving and sympathetic damsels. The ride is at once rambling but still engaging. It is as if we are involved in Moores’ and Jim’s own journey to discover what this strip really is about.

Jim Hardy is interesting because it tells us something about the uniqueness of the comic strip form. For all of its institutional constraints, this was among the most personal of modern mass media. The major electronic media that defined the twentieth century – newspapers, film, radio, television – were so collaborative critics often struggle to find in them some “auteur”, some way of aligning modern mass art with classic literature, art and music. But the comic strip is the product of a singular vision. Its world is established so fully by a distinct visual voice, its own cadence and tightly controlled point of view, illustration of character through unique line weight and even its own physics. It feels intimate, like a direct engagement with an individual imagination. At its best, the comic strip can involve us in ways closer to poetry or painting. By any critical measure, Dick Moores’ Jim Hardy was an unsuccessful, short-lived effort by a nascent talent. But its art, character arc and and humanity are anything but forgettable.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.