One of the pleasures of Al Capp’s Li’l Abner across the decades was that the strip never took itself or any other pop culture phenomenon very seriously. In fact, Capp may have been at his best in his absurdist parodies of pop culture fads, rising celebrities, and politics. Satirical proxies for Margaret Mitchell, John Steinbeck, Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, Marlon Brando showed up in the strip at the height of their popularity. Larger issues like the Cold War, student unrest, Third World politics all found their way to Dogpatch, or Dogpatchers somehow found their way to them. Ironically, what started as a comedy about a backwards and alienated community of big-hearted naives, was really illustrating in its own light way how interdependent and mass mediated the world had become by the 1930s. In Capp’s hands, Dogpatch is anything but disconnected from the rest of the world. The wide world rushes through the hillbilly berg.

Americans quickly embraced the hick comedy of the Yokums and fellow Dogpatch dwellers as soon as it launched in 1934. but arguably, Capp and the strip really found its enduring voice and role as a satire of contemporary culture later in the 1930s. Li’l Abner’s most famous and sustained parody is Capp’s relentless mockery of Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy in the figure of Fearless Fosdick. But before Fosdick became almost as prominent as Abner himself, Capp was learning about the traction and trouble he could get from poking at pop culture.

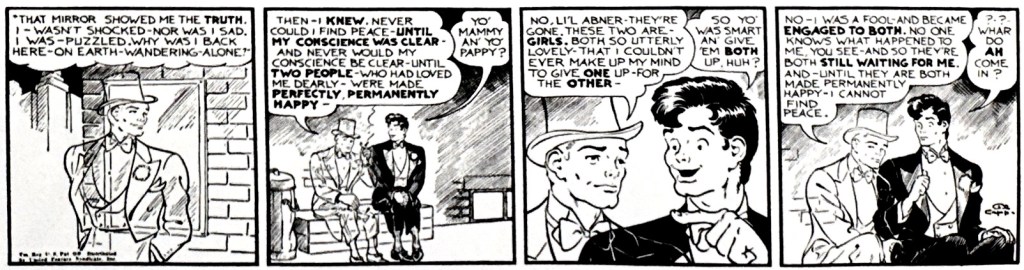

In his first attempts to bring pop culture tropes into Abner’s universe, Capp was not playing with genuine satire so much as alluding to familiar films, radio shows and novels. One of his first sustained parodies was a take on Thorne Smith’s Topper series, comic novels in which the ghosts of a roguish married couple of drunken socialites tries to liberate and loosen banking executive Topper. In Capp’s version a dapper spirit tries to find permanent peace by using Abner to make amends with two women the socialite had deceived. This sequence barely qualifies as cultural satire. It is more a bit of cultural referencing that would lead Capp over time into richer veins.

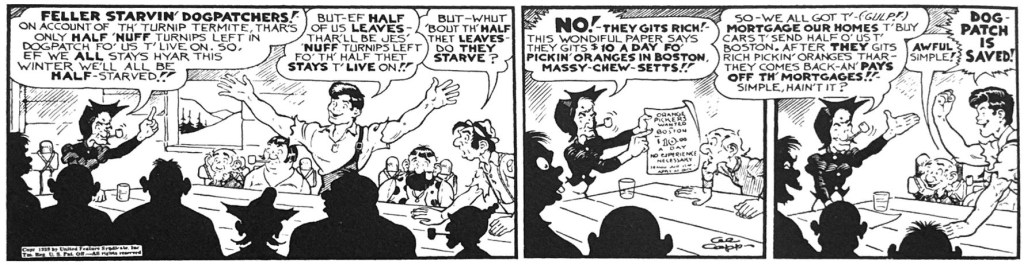

“The Grapes of Abner” episode in 1940 is also less a lampoon than a projection onto Dogpatch the basic situation of John Steinbeck’s enormously popular, Pulitzer Prize winning The Grapes of Wrath (1939) novel and subsequent film version. Just as the Joads and others fled the middle American Dust Bowl drought, Dogpatch’s turnip crop is hit by termites. While the Okies head west, lured by promises of fruit picking jobs, Dogpatch is conned into mortgaging their farms in order to pick a purported February crop of oranges in Boston. Like Steinbeck’s novel, this months-long trek north is a picaresque encounter with America, in-fighting by the hungry caravan, near-death experiences and the usual collection of Cappian cons and coincidences. In fact the Grapes of Abner conceit is a paper thin frame for business as usual in the strip. The sequence culminates in the Skraggs and Yokums feuding as a refighting of the Battle of Bunker Hill in Boston. Again, “The Grapes of Abner” is more allusive than satirical. But Capp is getting there.

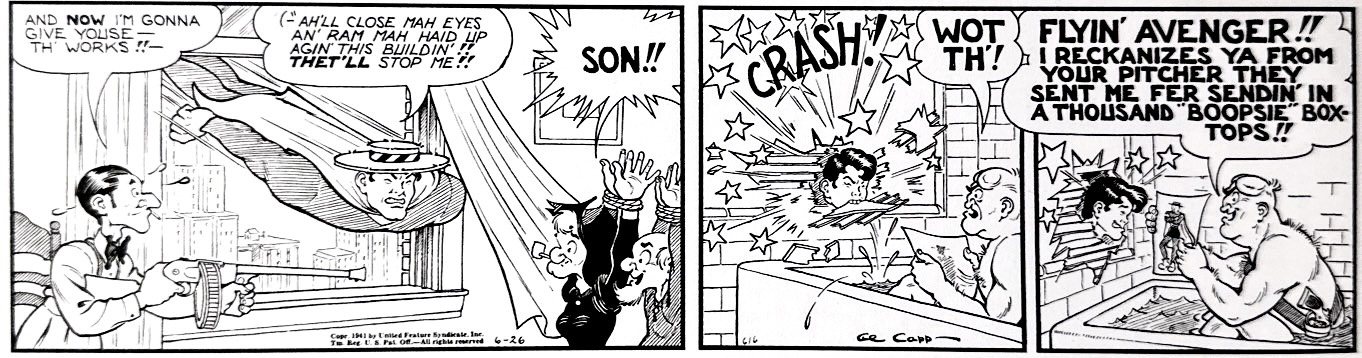

It is in his 1941 send-up of the still-new costumed superheroes that Capp hits a rhythm and depth for sustained satire. Only two years after the first appearance of Superman in print, the explosion of costumed, ridiculously super-powered heroes had already invaded comic books, radio and serial film. But Capp was among the first to poke at the overt silliness of these characters and detect the infantile fantasy driving the genre. Abner is recruited by panicked radio execs who are trying to conceal from a live audience that the voice of their he-man broadcast hero The Flying Avenger is played by a bespectacled pint-sized nebbish. When a swami in the adjoining radio studio casts a levitation spell on the Avenger, our stand-in becomes a genuine flying Abner “Ah cain’t steer mahself!”). In a compact satire that reaches across several weeks, Capp has his way with the goofy conventions and even dumber unanswered questions the genre poses. That the superhero fantasy is grounded in embarrassing fantasies of overcompensation and power is so obvious to Capp he tosses it away at first glance. Likewise, the fact that the whole point of the enterprise is driven by a sponsor aligning superpowers with eating “Boopsie Cereal” is just part of the background noise. He has more fun with the basic social challenges of someone free to fly around bedroom windows, (and so surveil) couples in bed or rooftop sunbathers. And of course there is the bone-headed vigilantism, which in this case recruits the hapless Abner into serving one side of a gang war. And then there is mastering the physics of flying.

In these early light parodies, Capp is finding his way as a social and pop culture critic, but he is also establishing satirical tropes that influenced subsequent generations of parodists, most obviously Harvey Kurtzman and his pop culture takes in MAD magazine a decade later. An unabashed absurdist, Capp used unbelievable situations, coincidences, screwball physics, big doses of irony and meta-fictional gestures as the centerpiece for comedy. As someone who rejected the faux realism of adventure and drama, he may have been best positioned to chortle at the ridiculousness of popular genres. Their laughably hyper-masculine fantasies. Their self-seriousness and bravado. Their total lack of humor or self-consciousness. Their grown men flying through the air in their onesies. What the hell are you people entertaining yourselves with, Capp seemed to be asking. How are you playing so easily into the hands of cynical businessmen who will say and do anything to sell you a bowl of cereal?

In his infamously ill-fated send-up of Margaret Mitchell and “Gone Wif the Wind” in late 1942 Capp starts developing more fully realized parody. Dreaming Abner into Mitchell’s novel as “Wreck Butler” to Daisy Mae’s “Scallop O’Hara,” Capp deftly uses his Dogpatch family as a repertory – “Ashcan Wilkes”, “Melancholy Hamilton,” etc. The sequence only lasted a few Sundays, but the story-within-a-story structure gave it greater weight and helped underscore Capp’s main satirical insight about the weird romantic attractions, repulsions and basically unlikeable heroine that drove America’s most popular novel of the time. If there is a central insight to Capp’s GWTW send-up it is from poking at the nonsensical relationships at the center of the saga, that Wreck and Scallop’s love/hate relationship is just too silly to be genuinely romantic. Poking through the pretensions of popular fictions with a dose of “truth” was how Kurtzman later described his satirical perspective in MAD. And Capp and Kurtzman seemed to share a distaste for the phoniness of mass culture, that popular fiction traded in ridiculously idealized visions of ourselves and unreal emotions.

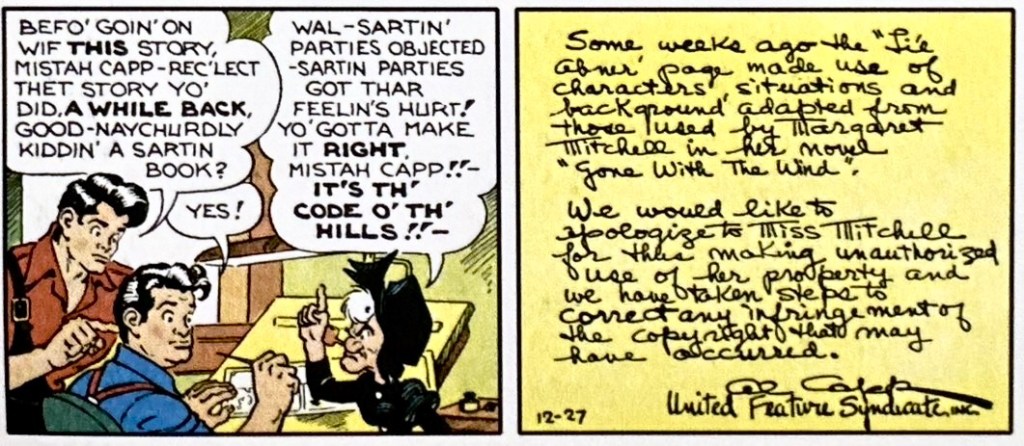

The one thing that “Gone Wif the Wind” demonstrated was that the Mitchell family had no sense of humor…none. The first Sunday installment of the story was met with the threat of a copyright infringement suit by Mitchell’s libel lawyer husband. He planned to ask for $1 in damages for every one of the 60 million+ newspapers in which Abner was published. Not only was the original satire arc shortened by the threat, but worse, the strip broke its fourth wall on Dec. 27, 1942 to issue a direct apology to Mitchel for unauthorized use of her intellectual property. It might be worth mentioning that John Steinbeck had a very different attitude towards Capp’s humor. Steinbeck, whose masterpiece Capp had burlesqued, wrote an effusive introduction to an Abner collection in the early 1950s. The Nobelist not only praised Capp as a great satirist but went further, calling the cartoonist one of our greatest living writers.

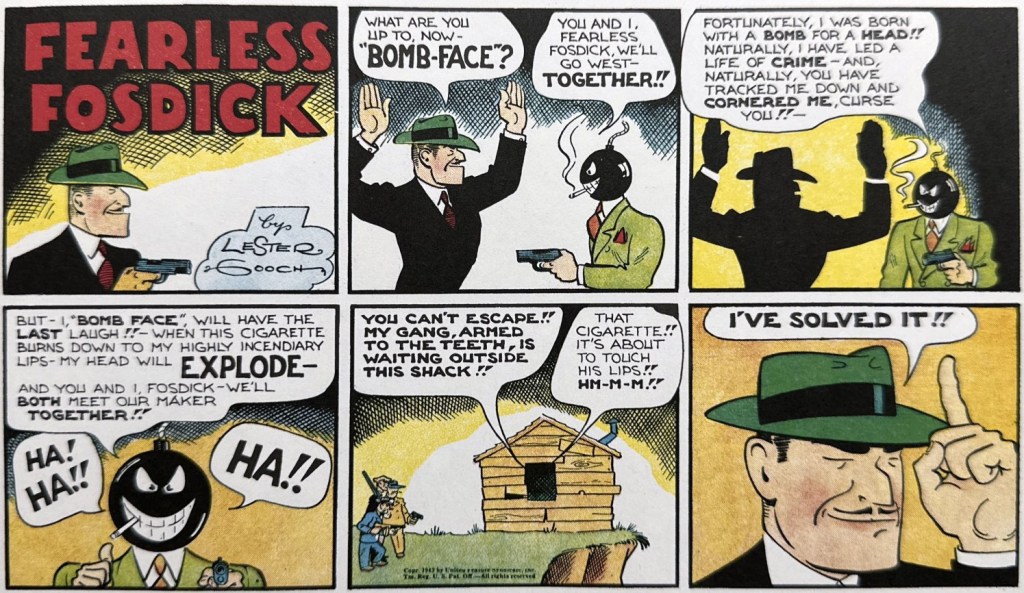

Wartime pop-culture proved fertile ground for some of Capp’s best sustained snideness. In August 1942 Fearless Fosdick made his first appearance. In this limited run, Capp poked at Chester Gould’s (aka “Lester Gooch”) famously improbable escapes for Dick Tracy. The bound Fosdick is dropped from a plane, leaving both readers and even Gooch clueless about how our hero will evade death this time. Capp may have been aware that this dig at Gould was not far from the truth. Gould admitted, at least later in life, that Dick Tracy was remarkably improvisational. He didn’t always know how he would get Dick out of some of the jams into which he drew him. For Al Capp, bad contrivance was part of the comedy in his strip. For Gould, it was part of Dick Tracy’s unintended weirdness.

Within the next year, Capp’s Fosdick spoof would widen and deepen, putting it on course to be one of the great pop culture satires of the last century. Sure, the strip-within-a-strip played off of Gould’s eccentricities: the ultra-violence, increasingly inhuman villains, and improbable escapes. But it was the unreflective seriousness of Fearless himself that seemed most interesting (infuriating?) to Capp. It was not just that the Dick Tracys or Supermen of pop culture suspended disbelief so radically, or even that their sense of masculine power was so, well, cartoonish. It was that they were so damned serious about it. Fosdick’s humorlessness, the total lack of self-awareness, let alone irony, is for Capp the original sin of our so-called heroic adventure fiction.

The weaknesses of the adventure genre were not a casual point for Capp. The cartoonist’s own creation story for the Li’l Abner strip makes direct reference to what he regarded as an unfortunate turn away from domestic and physical comedy strips in the early 1930s towards serialized adventure and continuities. Li’l Abner self-consciously tried to accommodate editors’ demands by marrying it with his preference for caricature, absurdism, comedy, family, character, and community. He was well positioned to goof on the the seams and silliness of the adventure genre. But in Fosdick he may be going even deeper. Capp goes at this character with a relentless ferocity that is mcuh sharper than his other satires. Fosdick is mayhem posing as order. His response to any infraction often ends in carnage. He is impervious to human appeals and often doesn’t even seem to hear anyone’s voice but his own. He is a thoroughly disconnected personality claiming to serve social good. According to most accounts, Chester Gould himself was not amused by Capp’s ongoing parody, and perhaps for good reason. There was something personal about Capp’s critique. Fosdick was not just comically hapless. He was a lampoon of a fascistic personality: authoritarian, humorless, dedicated to violence and a warped sense of order. Capp may have kept coming back to this particular satirical setup, and it may have resonated so well with readers, because he was poking at something deeper.

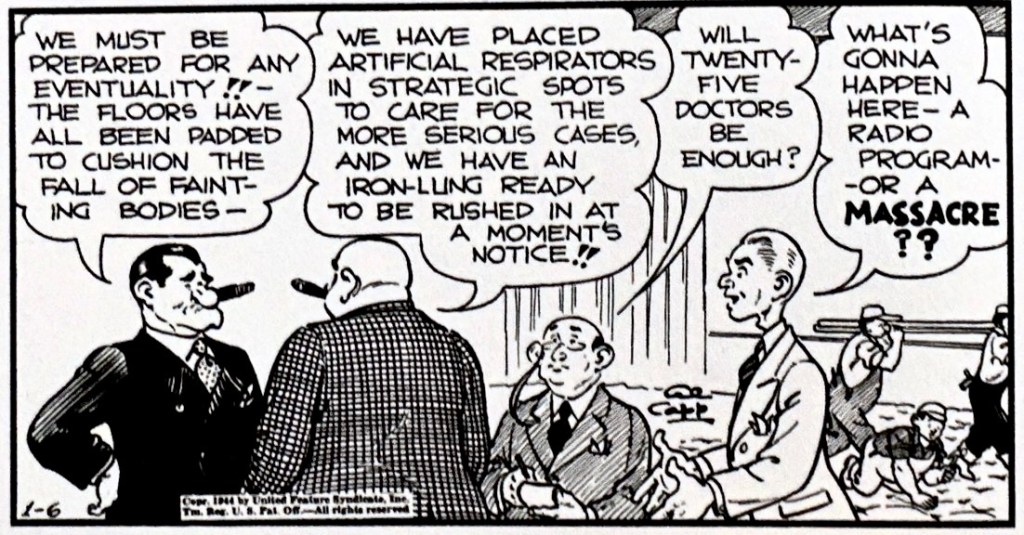

During the war years, Capp honed his satirical wit in taking on cultural trends, such as the rise of the teeny bopper and singing idols. His 1944 “Freddie McGurgle” episode is a nudge at the young Frank Sinatra’s meteoric rise. But more than that, he was lampooning a new kind of mass mediated fame and fandom. The screaming mobs of lovesick teen girls who later fueled the Elvis and Beatles phenomena in later decades began with Sinatra, who rose to record and radio fame as the Tommy Dorsey band’s lead crooner. Abner saves from suicide the despondent musical expert Concertino Constiato. He has scientifically determined precisely the kind of voice a “swoon crooner” needs to make teeny boppers faint, but he is hopelessly unattractive. Following the strip’s formula, a hapless Abner is recruited into someone else’s mad scheme, and he becomes Constiato’s puppet, a front man for the master’s swoon-inducing voice. Again following his “scientific” approach to marketing a modern crooner, Constiato names his discovery Freddie McGurgle and starves Abner to emaciation, yet another key to “swoon croon” success. Sinatra was famously skinny during the height of his 40s run. Freddie is an immediate radio hit, until of course the wheels fall off when Constiato fails to show up at a broadcast and the teen audience hears Abner’s real voice.

In the Freddie McGurgle cycle, Capp hits on a tenet of his cultural criticism, the vulnerability of mass audiences to the unprincipled manipulations of marketers and media kingpins. The real target of most Capp send-ups is the very mass media and marketing machines from which he himself profited. Capp enjoyed most lampooning national crazes real and imagined, whether it was Sinatra and Elvis’s crazed followings or his own fictional Schmoos and Kygmies. He seemed fascinated by the small, sometimes stupid ideas that could become national obsessions under the guidance of marketers and their media enablers. Li’l Abner was such a potent and popular satire because it was lampooning an historical confluence of forces that were still relatively fresh in American culture: mass media and consumer culture. Capp seemed to be fascinated by film, radio and television’s new ability to captivate so many American’s so quickly with a bad or silly idea.

And Capp is critical of both sides of this very modern phenomenon – the cynical, profit-driven kingpins who exploit these trends and the gullible audiences lapping them up. Both sides are fickle and insatiable. One of the hallmarks of a Li’l Abner satire of popular trends is how the media and audiences turn against idols as quickly as they deified them.

And to be sure, Capp is casting stones from within the glass house of mass media. Li’l Abner’s decades of popularity made Capp enormously wealthy, with spin-offs in film, comic books and stage musicals. And he was among the most prolific merchandisers of a comic strip creation. The Dogpatch characters were primary endorsers of Cream of Wheat cereal, and even the meta-fictional character Fearless Fosdick became the front man for a hair oil brand.

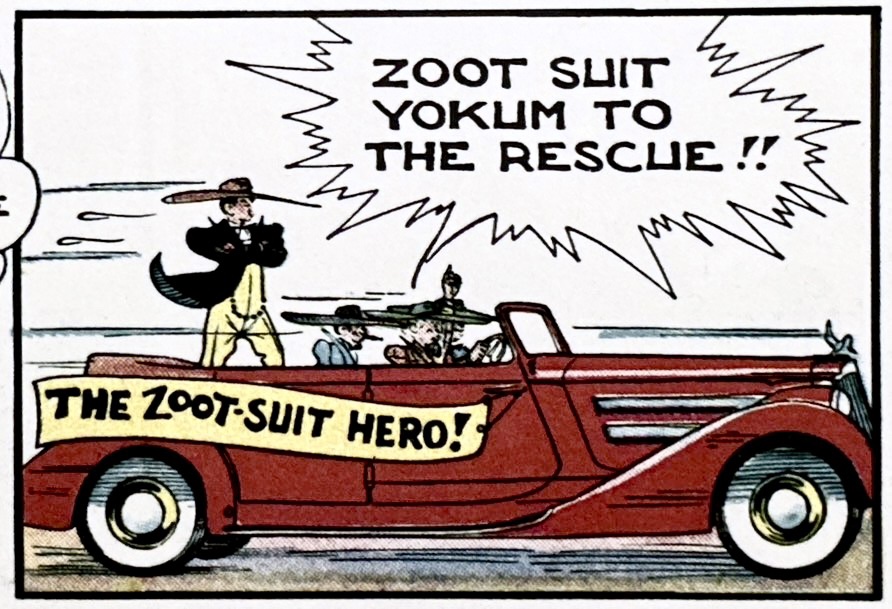

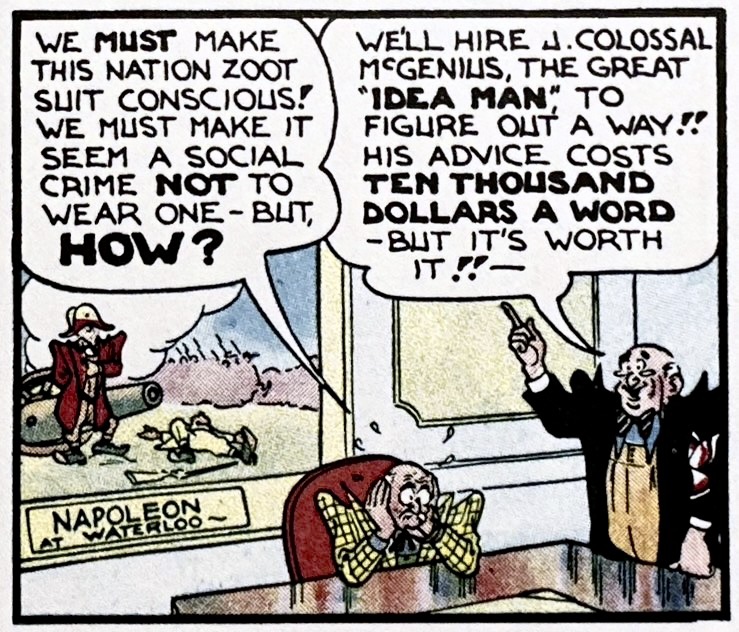

Capp’s richest satire of modern commercialism in the early 40s may have been his “Zoot-Suit Yokum” cycle in late 1944. The eccentrically shaped and boldly hued Zoot Suits were a fashion craze among urban Black and Latino men in the late 1930s and early 40s and soon were politicized by some segments of white American culture. The Zoot Suit style had massively padded shoulders, tight waisted and voluminous peg leg pants topped by a wildly wide brimmed hat. The trend became a point of pride in some communities, a way of rejecting drab urban workman dress. Aspects of the white mainstream, never at a loss for rationalizing racist contempt, pronounced the trend “unpatriotic” because it used considerable amounts of fabric during rationing-weary wartime. The controversy exploded in 1943 Los Angeles in the so-called “Zoot Suit Riots.” Groups of white servicemen decided to strip and assault Latino and Black Zoot Suit wearers.

In Al Capp’s hands, the Zoot Suit craze was emptied of its ethnic aspects and made into a simple battle for market share between Zoot makers and the conservative clothiers. “We must make this nation Zoot Suit conscious,” barks a Zoot magnate. But that is not enough. A higher order of mass manipulation is needed. “We must make it seem a social crime not to wear one.” Costly “idea man” J. Colossal McGenius” advises them to create a national do-gooding “Zoot Suit Hero” to compel mass idolatry and Zoot Suit adoption.

“Zoot-Suit Yokum” becomes the superhero of the moment, rushing off to solve fabricated crises. That is until rival traditional clothing kingpins enlist the same idea man to propose defusing the craze with a counterfeit Yokum who becomes an evil-doing villain against which the pliant public quickly turns. Capp’s critique of mass mania runs wide and deep in the “Zoot-Suit Yokum” episode. He sees manipulative and self-serving capitalist insiders playing with popular taste. At the center is the mercenary marketer who plays both sides so long as they pay his insane fee. And the headline-hungry and uncritical media machine fuels the fire. And the herd gets played easily by both elites. The sequence climaxes in Capp’s masterful Sunday strip above where he dissects all of the ways national manias warp every part of the culture: politics, mob violence, law, marital relations. As Capp would demonstrate in even longer satiric cycles with Schmoos and Kygmies, he was unafraid of comic excess, of totalizing his satire to depict America as a nation gone mad. Hs satire was most effective when it poked at democracy’s pesky and ironic tendency to adopt group-think, mob violence, constructing “others” as symbols rather than people.

Which is to say that Al Capp was giving us a comic critique of modern America from Dogpatch’s imagined pre-modern perspective. Li’l Abner’s hillbilly world was never mocked. It was the strip’s moral center. After all, the Yokums and their extended community of quirky characters were foils and counterpoints to a so-called “civilized” modern urban America of cons, mobs and an obsession with social and class rank. While comic, Dogpatch was a fully realized true community of wildly individual individuals, who were also sensitive to the individuality of others. If American readers of Li’l Abner thought it was a comedy of backward hillbilly manners, then the joke was on them. What Dogpatch’s imperfect humanity did was deny modern America its idealized self view, that it represented progress in thought, law, politics, humanity, freedom.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.