One of the longest-lived and popular Western series of the last century, Red Ryder (1938-1965) is barely remembered today…mostly for good reason. Unlike richer, historically-informed efforts like Warren Tufts’ masterful Casey Ruggles and Lance, Red Ryder was closer to Western genre boilerplate, The titular hero is a red-headed journeyman cowpoke who finds and resolves trouble wherever he roams. His woefully typecast sidekick “Little Beaver” was an orphaned Native American boy who provided identification for kid readers, a sounding board for the solitary and stoic Red, and comic relief of a distinctly stereotyped sort. In truth the strip made little effort to delve into character let alone suspense or high adventure.

While Red Ryder’s creator, Stephen Slesinger, was no writer, he was a brilliant multimedia packager. Slesinger made a name for himself throughout the 1930s for buying and leveraging merchandising rights to Tarzan, Dick Tracy and Winnie the Pooh. With Red Ryder he created the first comic strip conceived as a simultaneously launched multi-platform property aimed at achieving synergy across strip, film and radio serials, Big Little Books, comic books and eventually TV and toys. In fact, if Red Ryder is remembered at all today it is as the name behind Ralphie’s Red Ryder BB Gun in the holiday mainstay A Christmas Story. Slesinger successfully licensed his hero’s name to the Daisy company in 1940. It proved to be one of the longest-running licensed products in merchandising history.

While Red Ryder had all the hallmarks of a neatly packaged modern media commodity, the strip had one standout feature and the strip’s lone piece of authenticity – artist Fred Harman (1902-1982). Raised in Colorado around horses and ranches, Harmon was familiar with the terrain and the toil of cowboy life. A self-taught artist, Harmon got early experience illustrating for the Kansas City Star, in a brief animation partnership with an up and coming Walt Disney, and drawing for Western magazines and catalogs. His own attempt at a Western strip, Bronc Peeler (1934-38) never caught on, but it demonstrated a mastery of landscape and horse action that was miles ahead of other comic artists. Slesinger recognized Harman’s exceptional skill, brought him to New York and worked with hims for a year on Red Ryder before its 1938 launch.

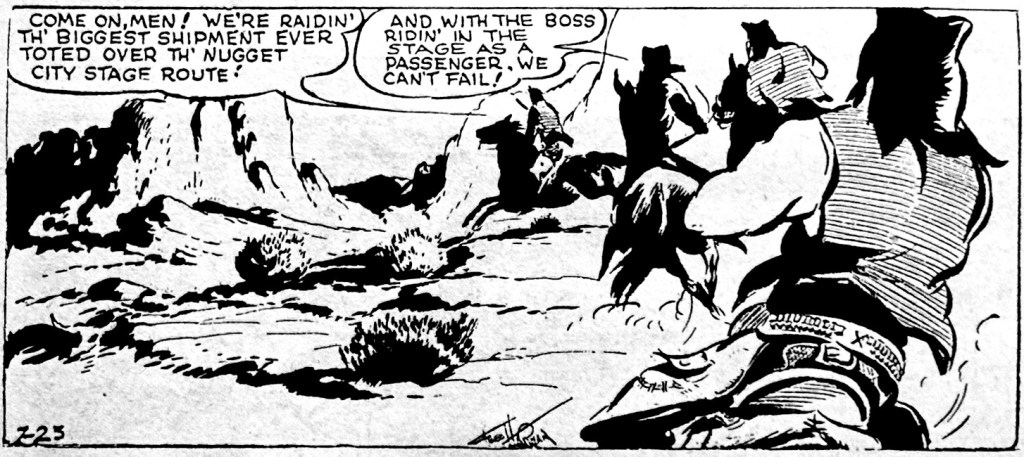

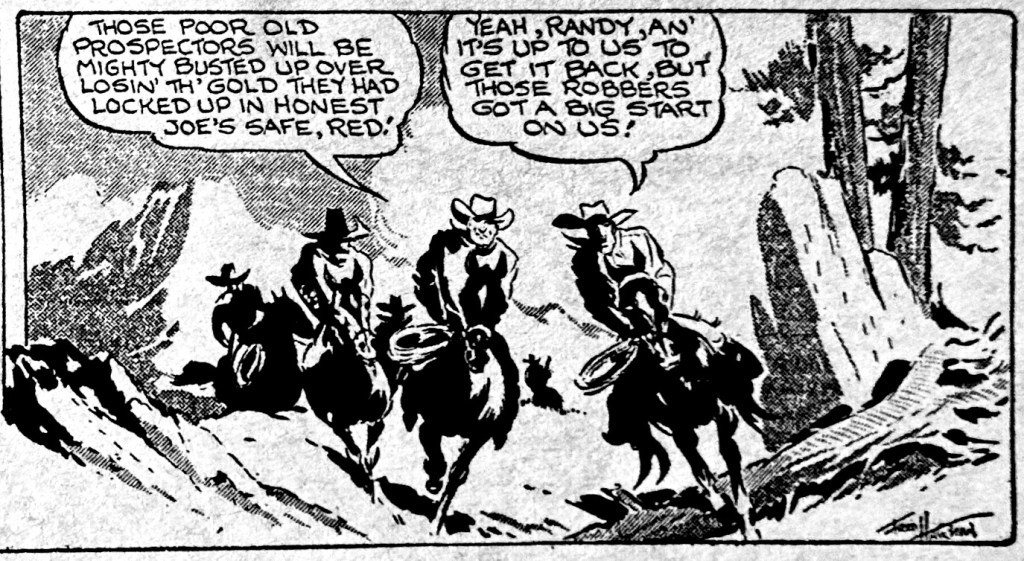

Harmon brought to the comics page a genuine sense of place. His backgrounds and landscape views gave Red Ryder a visual poetry and drama the scripting surely lacked. His double-wide panels use depth, foreground and background, to create a diorama. He gives us breathtaking vistas but is also sensitive to the challenge of the terrain itself. As only a seasoned man of the Plains might grasp, he shows the rough, unevenness of every inch of landscape his figures and their mounts need to navigate. In his hands, the West is a character, not a simple genre device.

Harman also had a strong lyrical understanding of panel progression and perspective. In the first strip below he brings us tighter into his main characters, progressing from panorama to wide to medium “shots” in a familiar way. but he packs such discrete visual drama into each panel, it feels as if each is telling its own story.

Just as aviation artists gave more realist attention to airplane rendering than they did to humans, Harman clearly loved drawing horses more than people. It is not just his dwelling on the powerful muscularity of horses but the ways in which he froze their posture and used sharp angles to amplify the action. You can almost hear the hoofbeats in some of these panels.

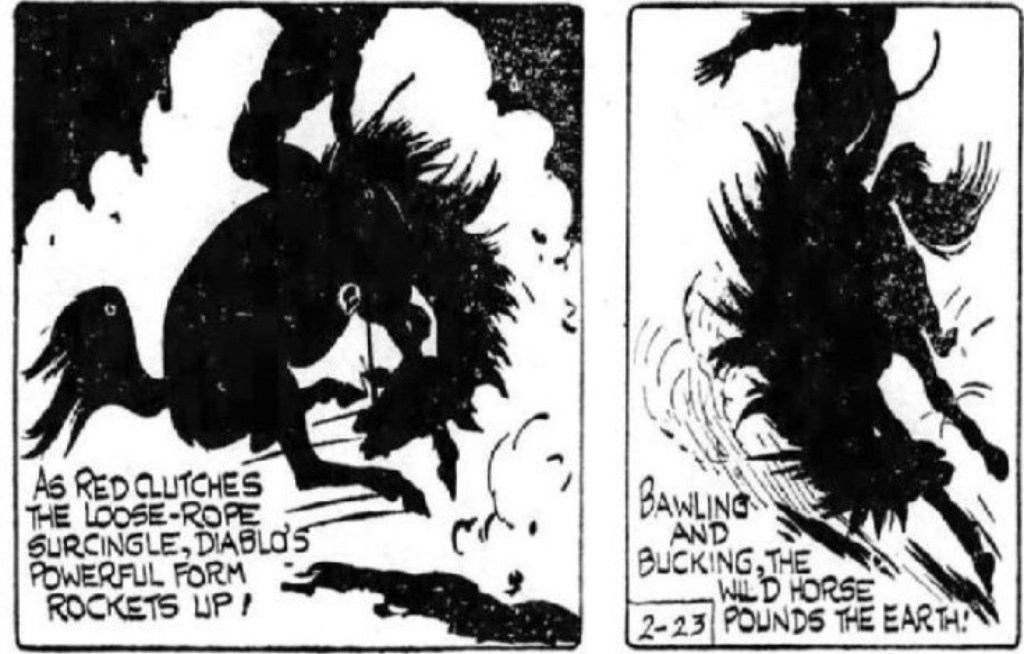

Most of the panels reproduced here come from the first few years of the strip in the late 1930s and early 1940s. By this time, Harman had honed his style well and settled into the cadence of panel progression. The sequence below depicts Red breaking the wild stallion Diablo with a wonderful kinetic quality that captures the danger and violence of trying to domesticate such a beast. And as is typical for this strip, the art is so much more communicative than the sorry scripting.

It is curious that Slesinger couldn’t have made this a more character-driven, engaging story. He had previously licensed the great Zane Grey’s Westerns for various property extensions, so he had a good example of the genre done well. But Red Ryder seemed to have a juvenile audience in mind from the start. The puckish Little Beaver character was the boyish point of audience identification and hero worship of Red the father/big brother figure. And the paper doll machismo of B-Westerns seemed pitched to adolescent visions of manhood.

But under Harman’s deft pen, Red Ryder makes the West itself the main character and the source of the strip’s depth. Parallel to the flat script is a daily visual statement about the hardness and beauty of the American landscape. In some ways it feels as if Harmon is telling his own story that is apart from the script. Awesome vistas, harsh terrain, man against an unforgiving backdrop, natural forces just barely under human control, a respect for nature’s moral indifference. These are the tensions and the tropes embedded in Harmon’s panels, apart from the immediate story.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Cartooning the ‘American Scene’: Comics as Modern Landscape – Panels & Prose