American popular culture took a number of odd turns in response to the trauma of the Great Depression in the 1930s. A fascination with pre-modern civilization, lost ancient worlds, aboriginal tribalism was one of the most pronounced that fueled comic strip fantasy. From Tarzan and Jungle Jim, to The Phantom, Prince Valiant and even Terry and the Pirates, Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy and Flash Gordon, the connection is obvious. At a time when most contemporary institutions were failing, Americans were understandably fixated on pre-modern, anti-modern, prehistoric and fable-like alternative worlds. One of the oddest subsets to this pop anti-modernism was the motif of fantasy monarchy, especially as a setting for comedy and satire.

It is too easy to mislabel these forays into feudal fascination as simple Depression-era “escapism.” But as the great culture historian Warren Sussman recommended long ago, calling popular art “escapist” misses the point and begs a much better question: what does the culture choose to “escape to?” For instance, the hyper-masculine male adventure hero of the 1930s was not an arbitrary phenomenon. It was an imaginative attempt to solve for some of the underlying cultural anxieties about masculinity in modern times generally but in the 1930s specifically. The showy, muscular antics of pulp and comic adventurers like Doc Savage, Flash Gordon, Phantom, The Spider or Tarzan answered the perceived softness of modern civilization. It was important to the cultural mission of the adventure genre often to pit our two-fisted, resourceful, agile, and sexually irresistible hero against pre-modern forces of nature and social violence as well as show his mastery of them. Maintaining a role for male power, prowess, attractiveness in an age of modern comfort, indulgence and consumption had been an American trope at least since the late 19th Century. But in the 1930s this anxiety was made concrete and urgent by widespread joblessness. The ineffectiveness of men and the special resilience of women was a theme we can see played out in some of the bestsellers of the decade, from Pearl S. Buck’s The Good Earth to Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind to John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. The popular arts had at least one response to that anxiety – the hyper-masculine adventure hero whose fantastic competence and mastery would evolve by decade’s end into pure juvenilized fantasy, the superhero.

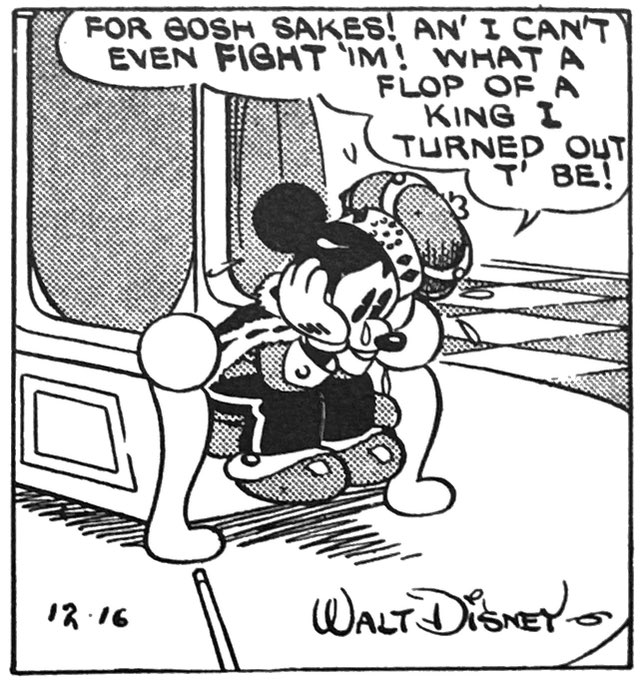

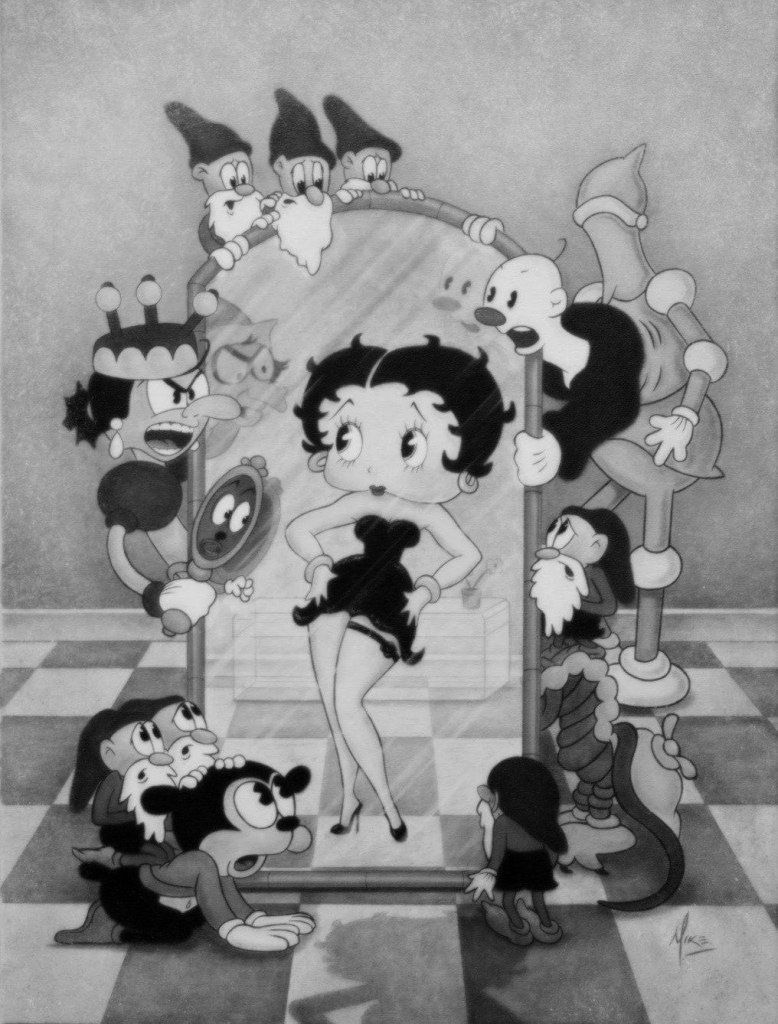

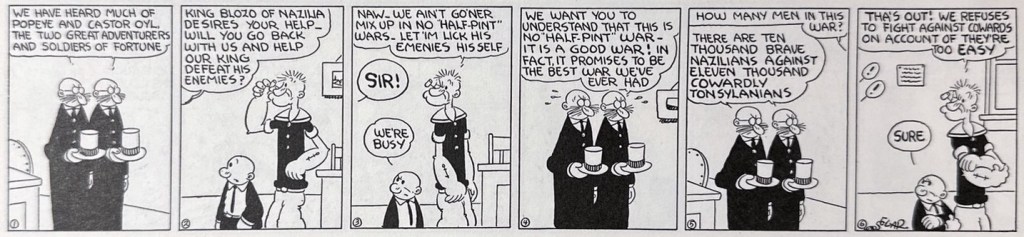

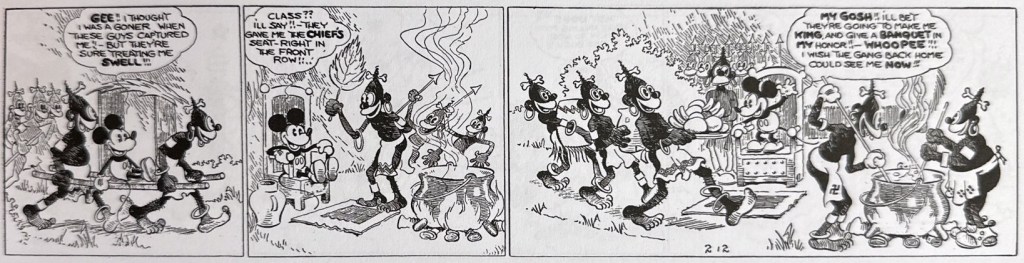

Meanwhile, the monarchical frolic in comedy is barely noticed let alone discussed among popular culture historians. But consider how many comedies of the Depression used vaguely eastern European or primitive tribal fiefdoms at some time or another. The very first Mickey Mouse adventure Lost on the Desert Island finds him at the wrong end of a cannibal tribe feast. Alley Oop is set in the prehistoric Kingdom of Groo in which Alley is at persistent odds with his hapless and insecure king. The Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup is set in a Freedonia which harkens back to the pre-WWI era of countless Eastern European and Slavic states forever at war. Otto Soglov’s The Little King was a sensation for The New Yorker that even helped set the minimalist cartoon stylings of the still-young magazine. There were high profile film versions of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves and The Brave Little Tailor, The Prince and the Pauper and a light-hearted Robin Hood. And even the Fleischer’s feature cartoon of Gulliver’s Travels focused on senseless warring between two kingdoms. The Fleischers also used the motif with Betty Boop, in their versions of Cinderella and Snow White. E.C. Segar sent Popeye and his Thimble Theatre to feudal realms at least twice, in an early 30s story to help King Blozo of Nazilia (“NAZI-lia?”) and the heroic sailor’s own failed turn as a benevolent “dictipator” of “Spinachovia.” And one of Floyd Gottfredson’s most political and best Mickey Mouse storylines involved Mickey becoming an American reformist in the mythical Old World monarchy of Medioka.

In most cases, these screwball kingdoms were occasions for featherlight political satire. Leaders usually were broadly caricatured as ineffectual, foolish, petty, protective of a power they neither earned or deserved. Almost off-handedly, these cartoons channeled American frustrations with political power but in a way that was safely removed from the hard and cold political realities of 30s America where the stakes were high and vitriol often extreme. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal was redefining the role of government in everyday lives and welfare. And while he was popular enough to be elected four times, FDR was not without heated critics. Demagogues from the right (Father Charles Coughlin) and the left (Huey Long) veered dangerously close to fascistic alternatives. A general disrespect for institutional authority can be seen in the romanticization of the gangster in film (Scarface, Public Enemy) and an embrace of extra-legal solutions even among hard-boiled police heroes like Dick Tracy and Red Barry.

And whether on a journey to a fairy tale past or an adventure to an international present, cartoon monarchies were always fundamentally silly. They were inherently political fantasies about obviously undemocratic societies, but they were at the same time politically un-serious. They offered safe spaces to exercise vague, unfocused hostilities towards the rich, the powerful, social oligarchy, aristocratic hangers-on, sheepish “masses,” etc. The impulses and resentments were real, to be sure, and you can see them repeated in all areas of 1930s culture. But in these cartoon fiefdoms the politics are defanged by broad stereotyping and slapstick antics. And yet, some of the best cartoonists of the 1930s, namely E.C. Segar and Floyd Gottfredson, steered this screwball monarchy sub-genre into genuine social satire but in vastly different directions. Popeye’s attempt at leading a utopian Spinachova fails miserably under the weight of his own political incompetence and the mindlessness of the mob he tries to rule. It is a true lampoon of both power and the people. As we will see in the next post, Gottfredson’s Medioka scenario was an American exceptionalist fantasy. Mickey brings both democracy and a good dose of Midwestern common sense to a corrupt and bankrupt monarchy. Like all successful genres, the screwball monarchy was a container that could be filled in many ways and with different political perspectives.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Popeye The Disgustipated Dictipator – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Flashing Flash: Or, A Paper Doll That I Can Call My Own – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Mickey Mouse Diplomacy: Disney’s Ambassador of American Exceptionalism – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Mandrake in Dimension Bonkers – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Jungle Jim Is A Ramblin’ Man…And Quite the Charmer – Panels & Prose

Pingback: When Superman Was Woke? – Panels & Prose

Pingback: They Had Faces Then: Close-Ups, 50s Photo-Realism and the Psychological Turn – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Amazon Dreams: Defending The Matriarchy in Depression Era Comics – Panels & Prose