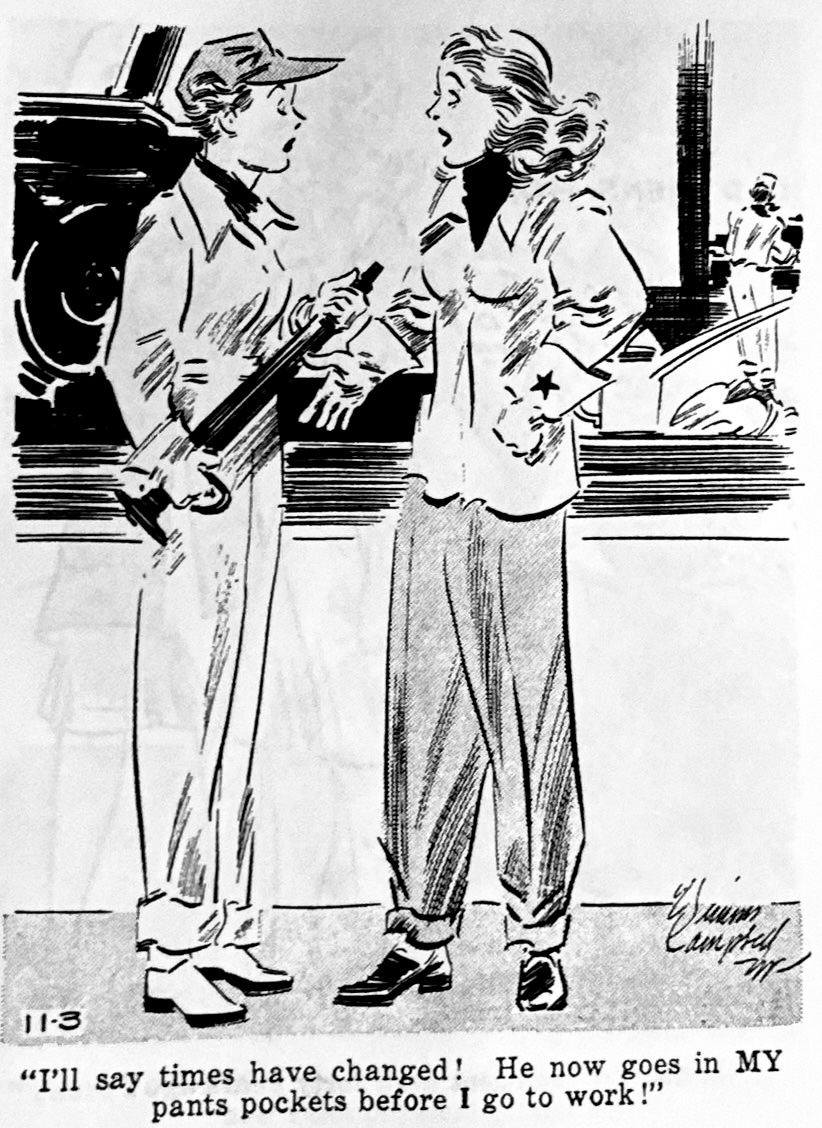

The role of WWII in the history of women, equality and feminism in America is widely known and usually mythologized in Rosie the Riveter tales. With many men abroad, women filled roles in industry and management that typically had been denied them. According to the thumbnail version, newly empowered women suffered a kind of cultural whiplash with the post-war return of men to the States. Industry, government and pop culture generally actively discouraged women from enjoying their newfound role outside of the home in range of unseemly ways.

The historical reality behind the Rosie the Riveter mythology is of course more complex than that capsule description suggests. E. Simms Campbell (1906-1971) captures some of that nuance and ambiguity in his Cuties series of one-panel cartoons that King syndicated to more than 140 newspapers, also collected into two “Cuties in Arms” volumes during the early 1940s. A prolific cartoonist for Esquire, most leading magazines of the 30s-60s, and tons of commercial art, it was unknown to readers that Campbell was among the pioneering Black cartoonists. In fact, aside from George Herriman, he was the only Black cartoonist to secure a distribution deal with a major syndicator. Early in his career, Campbell learned that focusing his pen and ink on curvaceous ladies (AKA “good girl” art) was his meal ticket.

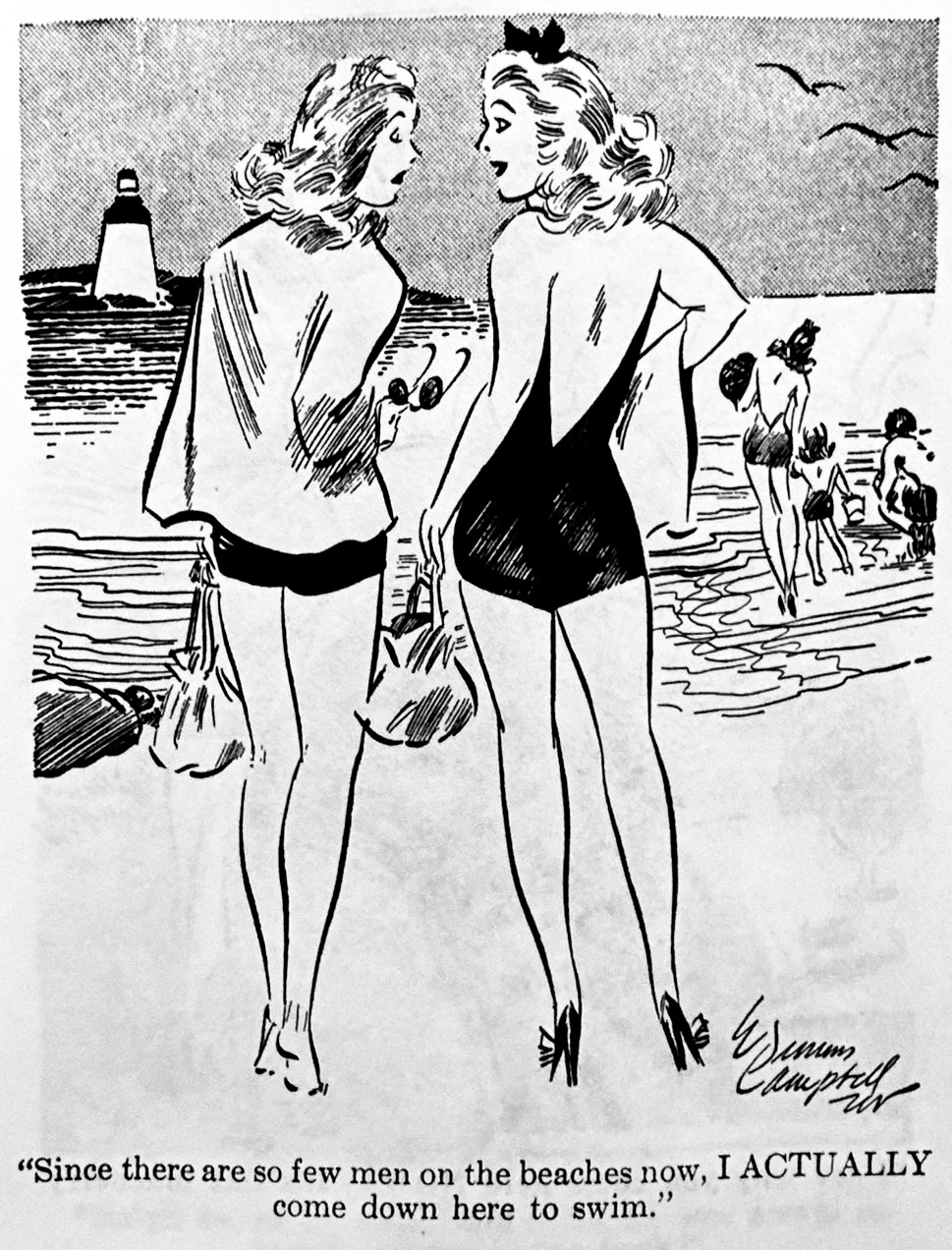

Setting aside Campbell’s status as a genuine pioneer as a Black cartoon artist, the comics themselves offer a subtle caricature of American women during wartime. Some of the images, like the one above, focus on the most obvious jokes about reversed gender roles and female bosses. The lack of men at home is a common trop, as is dealing with predatory male “wolves,” usually when entertaining troops at the local cantina. But Campbell also empowers his cuties in other ways, expressing their sexuality more explicitly, the often-mean competition among home front women over a shrinking pool of men, managing virtual harems of suitors and pen pals.

Campbell was an infamous workaholic, churning out massive amounts of commissioned commercial illustrations for advertisers, books and magazines over decades in addition to the daily Cuties for King. He was interviewed on several occasions, and would reflect on his work habits and artistic attitudes. He preferred the cartoon gag to other art forms, he claimed, because they activated the viewer in ways serious art did not.

“I prefer cartooning. You see, I like jokes, and it’s hard to put a joke into an oil painting. Have you ever noticed how quiet people are in art galleries? Well, I don’t think that’s what pictures should do to you. They should make you want to laugh, talk, shout, anything but hang your head.”

E. Simms Campbell

In the history of art and cartooning in particular, male artists have purported to depict women’s lives, experiences, thoughts and attitudes, often with disastrous results. Most of the flappers, wives, servants and office women depicted in 20s comic strips were crafted by male artists working from a small palette of gender stereotypes. And to be sire, Campbell flexes more than a few of those tropes in Cuties. But there is a broadness of sympathies and topics to these wartime depictions, along with an engaging illustrative style. Campbell draws a wonderful “good girl”, replete with all of the sexual protectiveness and desire, manipulativeness and materialism that typified the genre. Yet he never condescends. There is nothing ditzy, shallow or painfully innocent about these “Cuties.” He gives the wartime woman an adult bearing, a sense of self and of men, that suggests a richer kind of empowerment in the world than just toiling at an armaments factory. “Listen, Dearie,” the older matron tells the shapely ingenue, “If I were you, I’d get married before I was old enough to have the sense not to!” The woman at the bedside phone snarks at her absent man, “Well, since your’re working all night, dear, isn’t it difficult working with that ORCHESTRA in your office?” Campbell’s Cuties are obviously more than cute.

Others have written much more about E. Simms Campbell’s life and wide range of work than I need repeat here. I would recommend his entry in the American Art Archives for a broader sample of his work. A rich and illustrated biographical piece was published last year at The Saturday Evening Post. And you can find a deeper look at one of Campbell’s most significant and wonderful pieces, his cartoon Night-Club Map of Harlem at Slate. The map was just that, an oversized foldout insert for Manhattan Magazine Campbell drew in 1932. It reflects his personal devotion to the jazz scene during the Harlem Renaissance. Finally, I got acquainted with Campbell from the reprint of his wartime Cuties by Coachwhip Press.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.