Between August 1936 and March 1937, Mandrake the Magician and his right-hand man Lothar teleported into one of author Lee Falk’s most wildly imagined worlds, Dimension X. It was a universe of altered physics and futuristic super-beings: robotic “Metal Men” made of “animated metal”; “plant people”; ignited, swooping firebirds; man-eating plants; pacifist “Plant People”; and ruthlessly cruel “Crystal Men” who use the skin of captured men to keep their bodies shiny and ready to refract light. Ew! And, of course, no dystopia is complete without hordes of enslaved humans who dream of liberation. It was bonkers, even for a strip that had weird implausibility baked in. And while Mandrake’s side-quest into Dimension X seems like the most fanciful escapism, it was very much of its time.

Imagining alternative civilizations, both bright and dark, was a powerful cultural response to the Great Depression of the 1930s. It could be seen everywhere. The utopian Tibetan “Shangri-La” was at he center of one of the most read and viewed novel and film hits of the decade, James Hilton’s Lost Horizon. American-bred fascism was imagined into Sinclair Lewis’s dystopian novel It Can’t Happen Here, which even became a force in the 1936 election cycle. Different flavors of agrarian folk utopianism drove books as varied as Pearl S. Buck’s blockbuster The Good Earth, and John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. Romanticized nostalgia for the Antebellum South of agrarian society informed both Margaret Mitchell’s massively popular Gone With the Wind and the explicit manifesto of Southern Agrarians, I’ll Take My Stand. Science fiction and fantasy literature were still a backwater of American pop culture, but Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon strips and films helped mainstream a genre whose main feature was alien architectures, technology and cultural arrangements. And as we have seen in everything from Mickey Mouse to Alley Oop, Betty Boop to Popeye, the explosion of screwball monarchies in 1930s cartooning offered safe spaces for lampooning a feckless and futile political culture. Institutions appeared to have failed, and so many Americans were receptive to radical resets. For some this took shape in the unprecedented real political radicalism of popular fascistic and communist movements in the 1930s. But for most Americans the radical reset took place in the collective imagination, projected by popular culture. And this is why we can never dismiss this sort of fiction as simple Depression-era “escapism.” The critical question isn’t what Americans escaped from, but what creators and consumers elected to escape to.

Mandrake and Lothar enter Dimension X via one Professor Theobold, who has discovered this new dimension and built a gateway to it through “molecular disintegration” and “atomic bombardment.” Apparently an insanely indulgent parent, Theobold caved to his daughter Fran’s insistence she explore Dimension X. And so Mandrake volunteers to hunt her down.

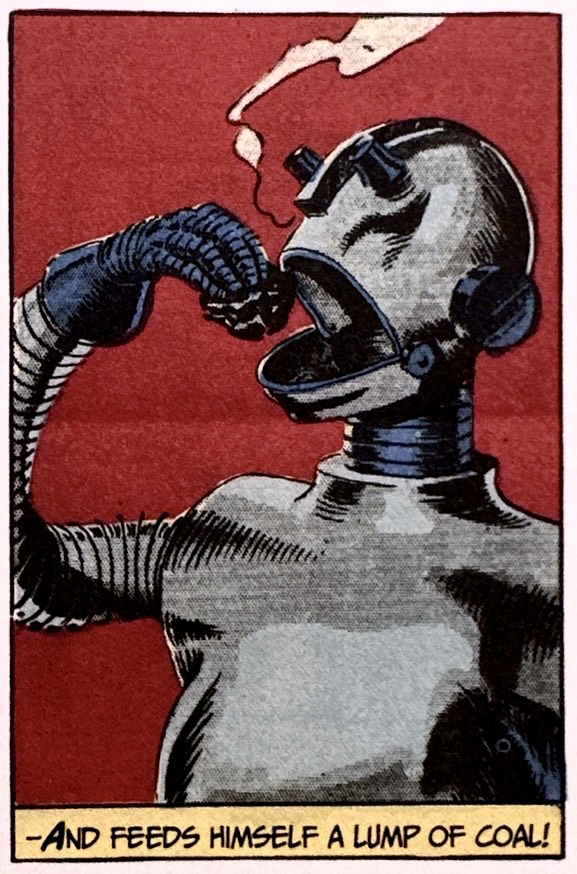

To Falk and artist Phil Davis’s credit, X is a richly imagined alternative dimension that uses the breadth of the Sunday page to sketch in some depth a flurry of sub-cultures and tech. Menacing robots were a dime a dozen in early sci-fi, but here they are an organic metal that can grow and mature over time, get nourishment from “coal, fine grease and oil.” The metal is cognizant, and so coils around slaves ankles can sense resistance and coerce submission. In many recognizable ways, Falk’s Meta Men foreshadow the basic tropes of our contemporary reticence around artificial intelligence: thinking machines as our masters. Under the alternative physics of Dimension X, the inorganic raw materials of the 1930s machine age take on a complexity and power beyond human control. Bu Falk’s fantasy reassures us that the most complex and inhuman systems have simple vulnerabilities. When you gorge yourself on coal, oil and grease, stay away from open flames.

Like the great pulp fantasists that preceded him like H. Rider Haggard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, H. G. Welles and even the creators of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon, Falk imagined alternative realms in racial and political terms. These worlds are comprised not only of different tribes but different species, with discrete values and technologies. While most of Dimension X’s factions are hostile and violent, Mandrake, Lothar and Fran get some respite from the local tree-huggers, the mud-eating and pacifistic Plant Men.

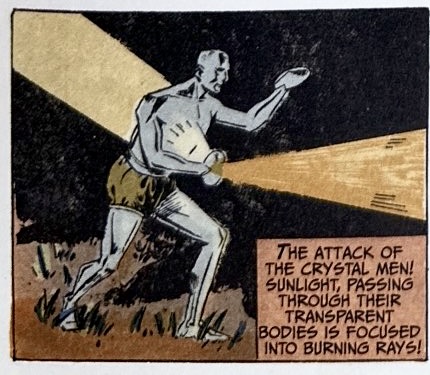

In fact in Falk’s new dimension, the emblems of high civilization, distance from nature, are aligned with inhumanity. The final and most brutal group in Dimension X are the Crystal Men, who operate like humanoid lasers, focusing the sunlight for their power and leveraging their crystalline composition for invisibility. Human skin, however, is essential to their maintenance, acting as polishing material. But again Falk arms Mandrake with a simple, organic fix, tossing rocks.

The inevitable human rebellion against the cold-hearted emblems of techno-oppression resolves this tale for Falk. It is worth mentioning that the usually stiff and uninspired Phil Davis is clearly reaching his peak using the Sunday canvas and palette. He visualizes key aspects of this alternative tech world with good illustrative draughtsmanship. The organic metallic houses seem to grow and breathe. The crystal bodies become frightening prisms of destructive light. He uses deep perspective to underscore the frighteningly clean and cool nature of metal and crystal armies.

And Davis is sensitive enough to understand that ultimately this is a war between cold scientific and industrial excess and organicism. The final battle against the Metal Men and Crystal Men with low-tech elemental stone and fire wraps the fable neatly with of box of populism, nostalgia and skepticism around the excesses of scientific progress. And in the ironic twist that can only happen in these 1930s alternative world fantasies, the restoration of popular power takes the shape of crowning an “Emperor” for X. Go figure. The nostalgic urge towards simpler political and social structures during the Depression were hard to kick.

The sheer volume of alternative world stories across all 30s media suggests that the connection between American popular arts and cultural need are profound and important. If only in the politically safe spaces of their entertainment, Americans apparently opened their imaginations to radically new ways of exploring some of the aspects of their real lives that were in tension: technology dwarfing human understand and control; the dignity of work in industrial capitalism; humane sustainable political and social structures. Echoes from all of these anxieties can be heard in imagined “escapist” fare like Mandrake’s Dimension X. In them we don’t see Americans fleeing from their experienced world so much as using the imagined world to play with them in safe but meaningful ways.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Shelf Scan 2024: Reviving Calvin, Nancy, Flash, Mandrake and Popeye…Again. – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Baby Mandrake’s Evil Twin? – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Mmmm…Coal!: Mandrake’s Metal Men Are Hungry – Panels & Prose

Has this storyline ever been reprinted anywhere?

Yes. I found it in the Titan reprint of the first years of Mandrake Sundays.

Thank you!