Jimmy Hatlo’s They’ll Do It Every Time (1929-2008) was as long-lived and beloved as it was throughly benign. To be fair, this single-panel museum of petty grievance had banality baked into its title and premise. The actual identity of the “they” is kept usefully loose enough to encompass an “other” of our choosing, but most likely all of humanity but us. And their “doing it every time” is by definition rote and predictable. But of course it is the aching familiarity of Hatlo’s observations that gave the strip purchase. Widely praised for poking at the small hypocrisies, human foibles, bombast of everyday existence, the strip had a special populist appeal. Hatlo was inspired by readers who submitted ideas and got daily credit with a “tip of the Hatlo hat” and even their name and street address for millions to see. Indeed, that was a vastly different era when it came to personally identifiable information. And yet, not so ancient. We can see in They’ll Do It Every Time predecessors of both user-generated content (UGC) and observational humor.

But Hatlo’s work raises something even more important about the nature of the cultural work that the American comic strip took up in the last century. From its earliest days, the comic strip was uniquely positioned to scrutinize the small, the everyday, even the petty aspects of American manners and morals that other media had neither the patience or tools to handle. In a handful of daily panels, the original short-attention span theater, comics had to make a lot out of a little. Precursors to Hatlo’s critique of petty hypocrisies and frustrating foibles are almost too numerous to mention. Early newspaper strip artists often created characters around familiar quirks: Superstitious Sam, Mr. Jack (philanderer), Peter Putoff (procrastination), Sammy Sneeze, The Almost Family (lateness), Mrs. Rummage (bargain hunting). Gus Mager’s cast of Monks included “Forgetto” and “Henpecko”. Even more prescient were Maurice Ketten’s The Hurry Up New Yorker, a send up of busyness, or The Outbursts of Everett True, which literally bashes the minor irritants among us. Hatlo worked in that same spirit, calling out the office blowhards and prevaricators, skinflints and hectoring spouses, misdemeanors of hypocrisy, the tiny ironies of existence.

While They’ll Do It Every Time clearly flowed from a comic strip legacy of grievance comedy, it began in 1929 at the San Francisco Call-Bulletin as a happy accident. Hatlo was working on the sports section when he was asked to provide a last minute replacement for an absent strip. It quickly resonated with readers, who soon sent in ideas of their own. The popularity of the strip cannot be overstated. Not only was it widely syndicated, but clipping and sharing its spot-on observations, pinning them on office bulletin boards and refrigerators, was a commonplace. In fact, at one point in 1945, a 32-card series of Hatlo strips were distributed in Mutoscope vending machines. “Guys and Dolls” scribe Damon Runyon introduced one of the first of many paperback reprints of the comics by declaring “Hatlo is today one of the greatest cartoonists the newspaper business has ever produced.”

There was an evolution to Hatlo’s targets across the decades. The strip really took off under a better syndication deal in the mid-1930s, and across the 30s and wartime years Hatlo aimed more for the minor and unavoidable ironies of life, the domestic sphere and hypocrisy in a minor key. An electrician gets dirtied servicing a coal plant before his next call to, ironically, a white linen shop. Holiday resort maps are chided for making everything on site seem deceptively close. The birds you feed during their lean winter months come back to devour your grass seed in the spring. Small town speed limit signs intimidate newcomers but are ignored by townspeople. The adventurer who enlists in the army to see the world gets stationed next door, while a homesick family man is stationed thousands of miles away. A wife showily snips elaborate recipes but routinely. cooks pork and beans for dinner. A proud father crows over siring a baseball team of sons but leaves it to his wife to play with them. And there is a parade of social irritants: pranksters, braggarts, name droppers, skinflints.

Artful Banality

His was not a talent for identifying the minor insight but for using his cartoon arts to amplify them into something that felt to readers substantial and meaningful. The appeal of TDIET was not rich satire or new insights. It was about ratifying those everyday grievances with the that democratic world of “others” and offering the reader a small moment of minor authority and gentle superiority to crowd of which he or she is a part. At its core was Hatlo’s cartooning talent. His character names were among the most entertaining and truly satiric part of the strip experience. While TDIET was not a serial strip, it had recurring characters and names. The most notable were the long suffering corporate cog Tremblechin who along with her puckish daughter Iodine, who successfully spun off into her own Sunday strip and comic book series. But there was also big boss Bigdome, the office drones Cheddar, Belfry and Vermin. Hatlo had a strong cartoonist’s sense for being pointedly silly. Character names like Dimbulb, Linseed, Dr. Phootnote were meaningful tags that deepen the strip’s minor insight. Ragmop, Follicle, Chloramina, Hewline were all cartoonish extensions of Hatlo’s art style, another way of comically reducing his hapless humans. He was adept at doublespeak, mocking technical jargon and the authorities that spout them: professional diagnoses of “rhinitis creepus” and mechanics’ explanations of broken “torsional damper tappets.”

And visually, Hatlo was deft with the big-nose style. Not unlike Dr. Seuss, he drew a rubbery reality of loose, thick ink lines and elastic edges. He was caricaturing grievance, and the visual voice of the strip embodied this.

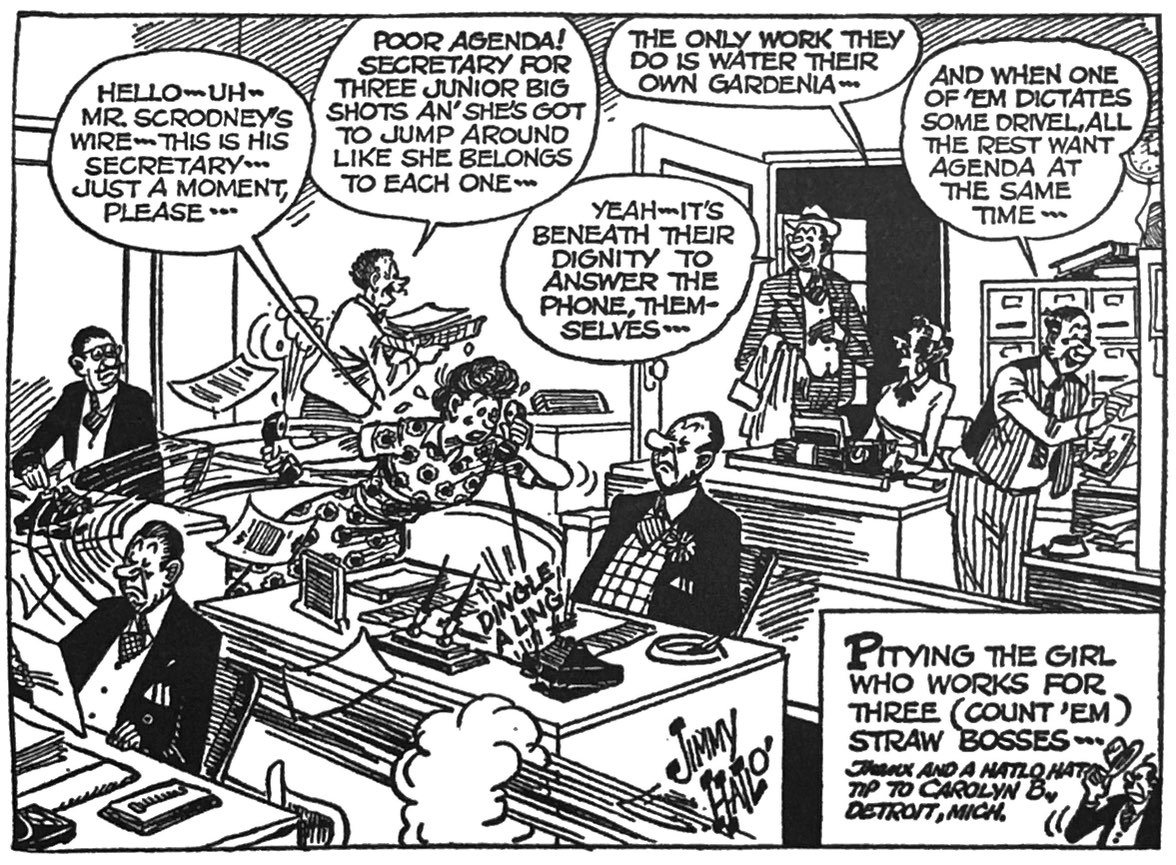

There is more edge in the art than in the gag itself. No one is especially attractive in Hatlo’s America. He uses cartooning to level all of us as wimpy, servile, fearful of institutional authority. They are all depicted as weak chinned, unassertive, subservients who whisper and snipe clever asides outside of earshot. Tremblechin is in name and image just the purest expression of almost all office workers in his world. Perhaps unwittingly, Hatlo is dissecting the Grumbling American, a modern middle class that is cowed by its domestic and professional institutions and can only assert a shadow of independence through ineffectual grousing, of which TDIET is an outlet.

The buttoned down world of Hatlo’s America is clearest in the quiet hell of the post-WWII workplace. As the strip moved into the 1950s, it took managerial, corporate hegemony as its primary subject.

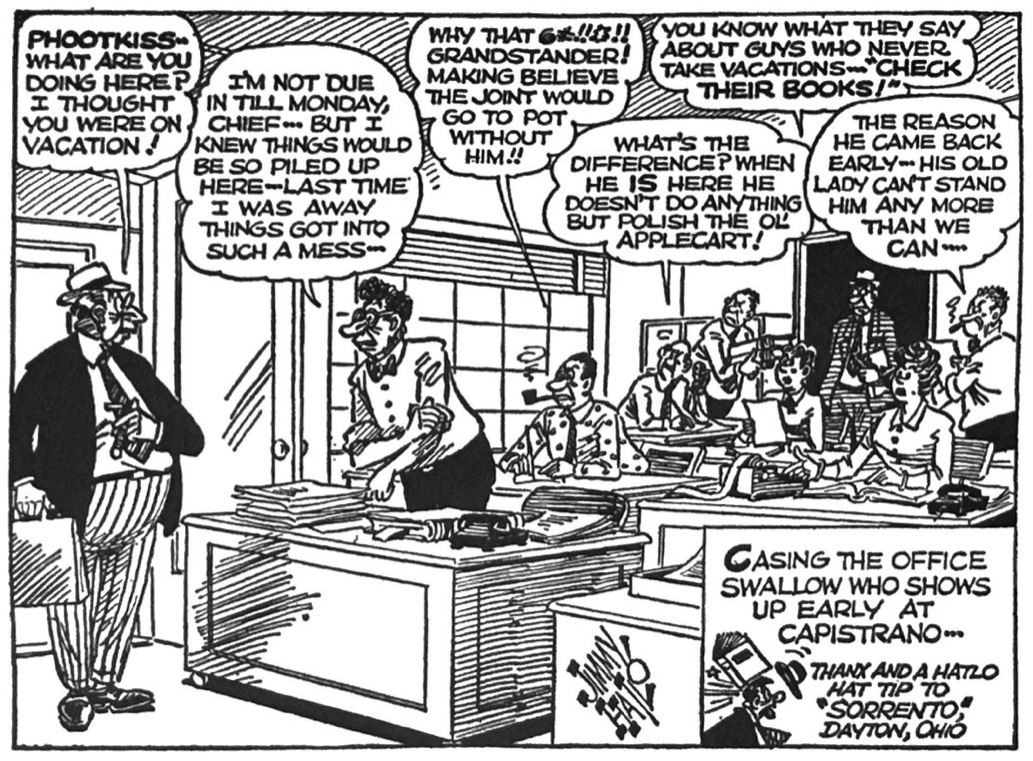

Hatlo effectively frames the middle class workplace dynamic as an isomorphic tableau. The skewed perspective usually focuses our first glance into the traditionally strong left third of the frame to quickly define the infraction and then capture layers of fellow workers viewing and commenting on the central sin. The vivisection of “apple-shiner” Phootkiss (above) is a great example of Hatlo’s cartooning skills for building a familiar office irritant into a cathartic tableau for readers. The situation is as simple as it is familiar: the office suck-up stealing credit for someone else’s insight in order to impress the boss. But in the character’s gait, that big black mass of Phootkiss snapping up someone else’s work, “ZOOM”ing into Bigdome’s office with a desperate, cloying earnestness communicates volumes about the sensibility of this schnook. The speed with which he sees his chance to make an impression, is made to feel like a reflex here. The open-mouthed, pie-eyed look on his face express a kind of risible servility and obliviousness to how his colleagues see through him. The real energy of a Hatlo office tableau is not in the central insight so much as the color commentary of his Greek chorus of co-workers. They provide the larger set of details about how characters like Phootkiss work: making others seem dumb, minimizing their own errors, effecting executive style. And this is where Hatlo activates his audience identification. He is speaking to a middle class of grumblers and commiserators, anonymous office drones finding solace or identity or a semblance of dignity in grievance,

The strip’s increasing focus in the post-WWII years on the white-collar office tracks the larger shifts in economy and culture. The massive expansion of corporate, small business and government bureaucracies after the war was a signature of 50s life. Hatlo’s was among the only cartoonists to take this new environment and its politics as a central subject…and depict it as a kind of purgatory. The sins are a blend of systemic abuses of power (unreasonable bosses, clueless executives, nepotism, office tyrants, pay inequities) and personality quirks (shirkers, suck-ups, relentless borrows and knuckle-crackers). The conformist genius at the heart of TDIET was that Hatlo conflated the systemic and the personal; the baked-in inequities and managerial dulness of the corporate workplace are no different from grating personality types. Both are presented as inevitable, natural, incontrovertible. Cultural historians often overuse Antonio Gramsci’s theory of “hegemony” to describe something like this. The ruling class interests in a society are imposed not by explicit politics or coercion but by making the status quo appear natural. Hegemony even allows for dissent and dissatisfaction with the status quo, so long as it is channeled into forms that never really challenge the status quo. In other words, the resentful grumblings of Hatlo’s office drones are a way of engaging and diffusing genuine class, social and power relations. Compare TDIET’s take on bosses and workers with similar themes in Syd Hoff’s radical “Ruling Clawss” cartoons in the Communist Daily Worker. Hoff frames his wealthy figures as genuinely infuriating: at best insensitive to labor and at worst downright malicious. In contrast, Hatlo’s Bigdome is self-absorbed and often feckless, but it is less a function of social class than personality. The hard edges of capitalism are made as elastic and soft as Hatlo’s ink line…ultimately as benign as the strip itself.

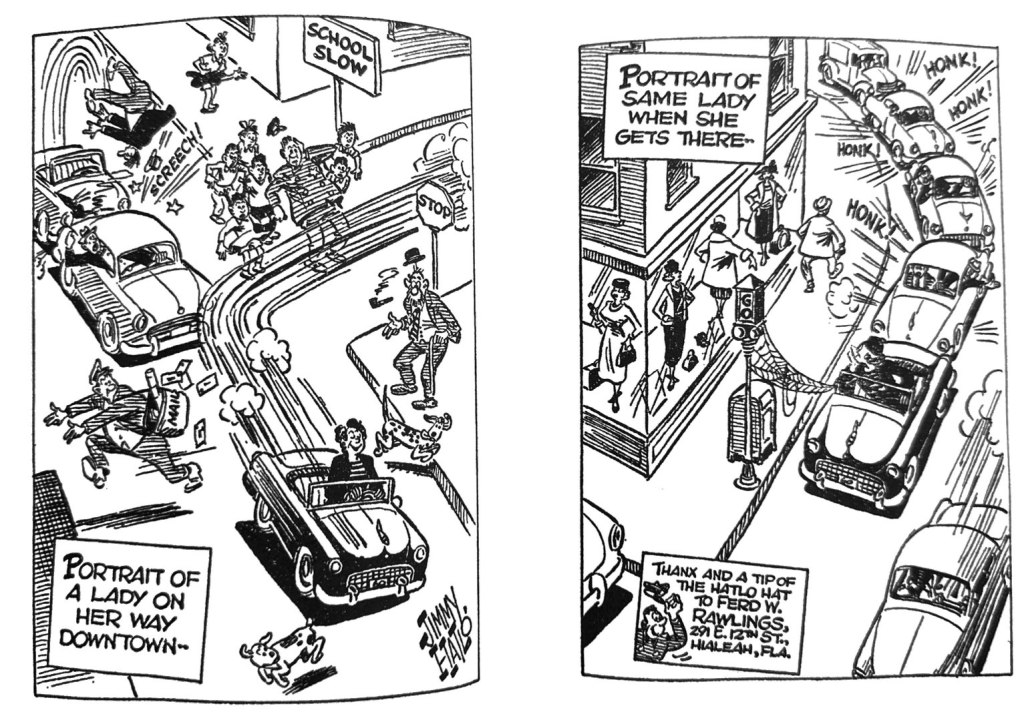

Intolerance was key to TDIET. The reigning spirit of the strip was judgment. A narrow understanding of gender, social propriety, manners, etc were always in place. Hatlo’s America was the inverse of screwball comedy, which was all about antic disruption, social and physical subversions. Here the resentments are voiced as asides and whispers, the absence of conflict and confrontation. Surface politeness is preserved and grievance is subverted into ineffectual grumbling.

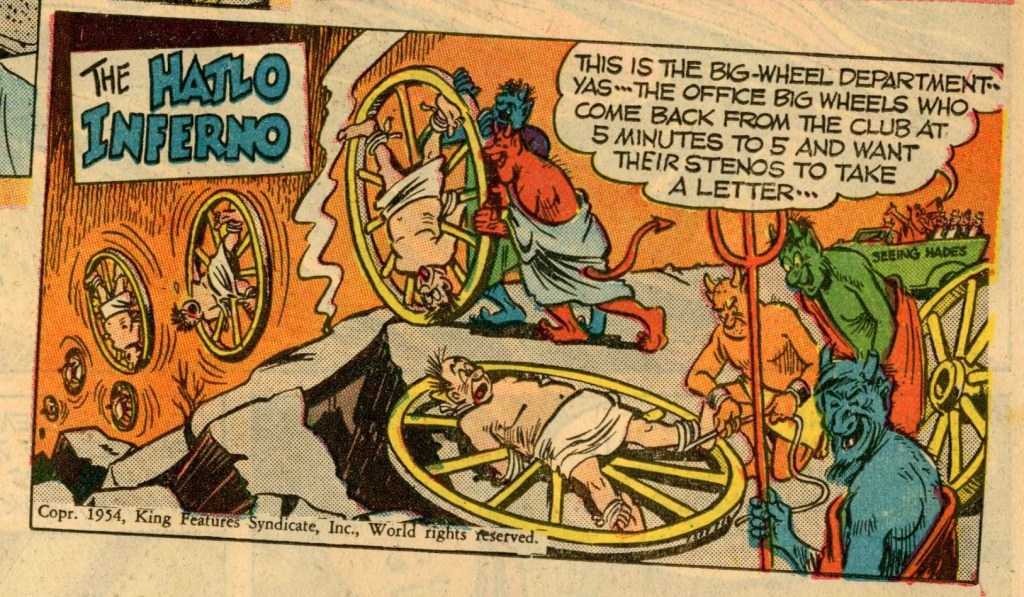

Which is not to say that the grievances aren’t real or deeply felt. If there is any doubt that there is real anger and resentment behind Hatlo’s and his readers observations, Hatlo tips his hand in a few ways. During the mid 1950s he invented his Hatlo’s Inferno where we witnessed Dante-esque eternal punishments for the minor sins “They” “Do Every Time.” In this same period he starts incorporating into many strips a frustrated figure musing an “Urge to Kill” in response to the daily infraction Hatlo is illustrating. Within the safe space of Hatlo’s cartoon cavalcade of light-hearted complaint, an id lurks with real resentment.

“They’ll Do It Every Time” is more about the viewer than it is about the purported objects of the jibes. There was rarely anything especially insightful or deep about Hatlo’s benign satire. It was observational humor at its simplest, depending on easy recognition of the blowhard, the office know-it-all, the lazy husband, heckling wife, little ironies and hypocrisies of everyday life. What was really important and appealing here was the posture of the grumbling, mildly aggrieved middle class viewer. Hatlo and others in the benign satire genre craft for the viewer a knowing, bemused, lightly frustrated and mildly superior position both in and against the rest of the world.

To understand Hatlo is to understand the gentleness of comic strip satire. Hatlo raised genuine grievance, even issues of class tension and divides but did so in a way that both registers and diffuses the conflict. He conflated individual hypocrisies of human nature with systemic inequities and unfair exercise of power. These are all problems of personal malfeasance or just ironies of life and so natural and immutable. The strip bounced around different areas of American culture, from marriage to workplace to sidewalk. But it was all contained by the individualizing frame of “They’ll Do It Every Time”. It was a reassuring salve and reinforcement for the modern grumbling American. The frustrations of modern life – the social, economic, political, class, labor, gender tensions – are real, but ultimately inevitable. As another benign cartoon satire of the post-WWII era would also suggest, “Grin and Bear It.”

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.