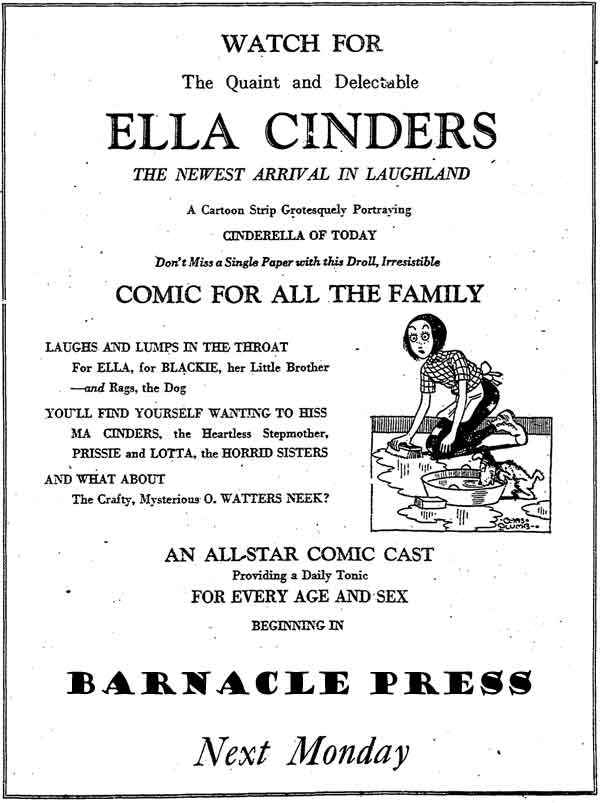

Ella Cinders (1925-61) was a female comic strip character with genuine character. And this is no small thing in an era of flappers, housewives and career girl stereotypes. While overlooked and under-appreciated, there have always been women both drawing comics and depicted in them. In the 20s and 30s alone we can point to Winnie Winkle, Tillie the Toiler, Dixie Dugan, Polly and Her Pals, Blondie, Connie, Fritzi Ritz, etc. But aside from the most visible heroine of the 20s and 30s strip, Little Orphan Annie, few of these female figures rose above bland cut-outs for the generic idea of the “New Woman.’ Even in the late 1940s, in the crop of more adventurous “Dauntless Dames,” that Trina Robbins and Peter Maresca featured in their wonderful new book, most heroines asserted their presence into the outside world more than they did assert an identifiable personality. Male helpers or wise-cracking boy sidekicks tended to provide the action and sharp banter. Aside from Annie, Dale Messick’s Brenda Starr (1940) is the first leading woman in comic strips to assert ambition and a full range of emotion.

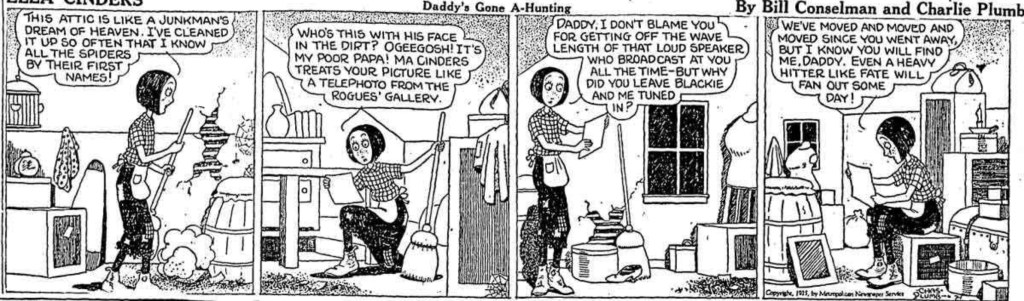

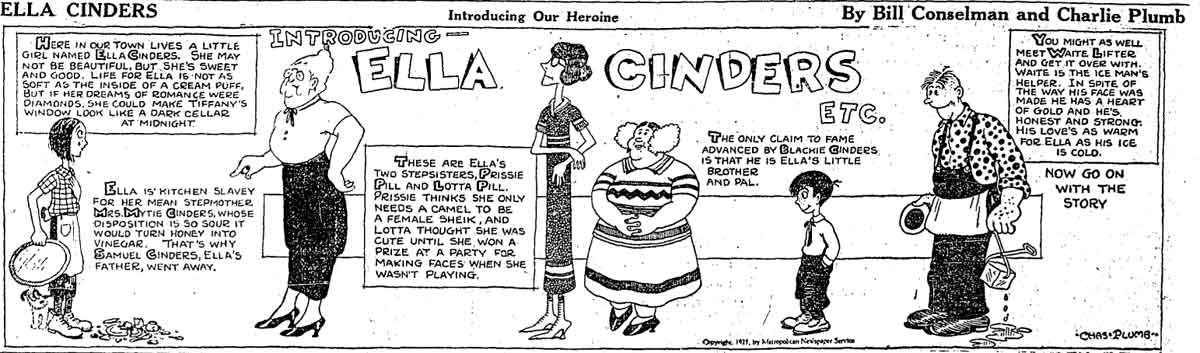

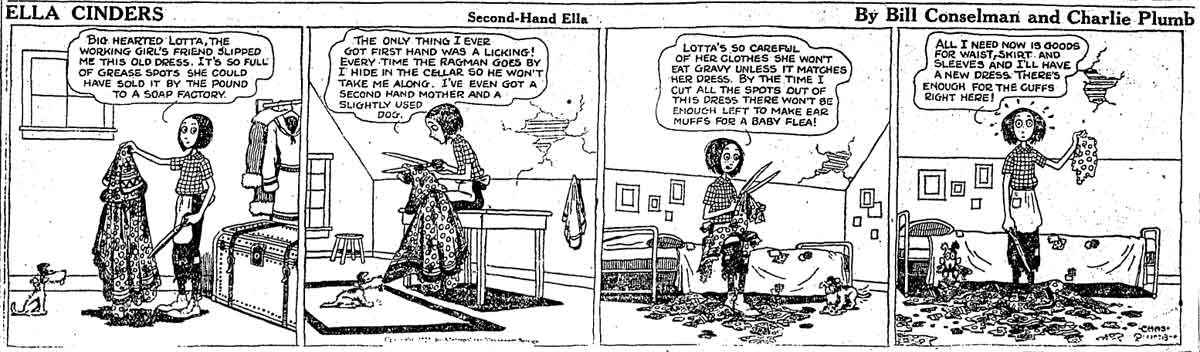

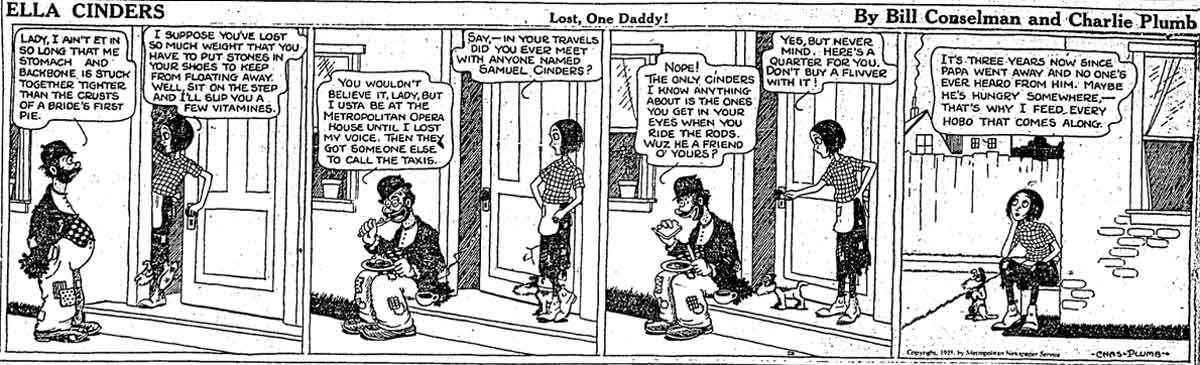

Well, except perhaps for Ella Cinders. Ella was different. Conceived as a modern Cinderella by Los Angeles Times writer Bill Conselman and staff artist Charles Plumb, Ella showed depth from the beginning. Enslaved by her tyrant stepmother Mrs. Myrtle Cinders and stepsisters, the lank Prissie and stout Lotta Pill, Ella was loving towards her kid brother Blackie, heartbroken by her absent father Samuel, self-deprecating and insecure in her servile role, but also wildly ambitious for a life of stardom. And we see all of this from her in the first two weeks of the strip’s premiere on June 1, 1925. In a way that is rare in the comic’s medium, Conselman’s Ella engages us almost immediately with empathy for her plight and vision. Her lengthy, internal monologues are often insightful about herself and other characters, and so share more with Gray’s Orphan Annie than the office gags of Winnie or Tillie. “The only thing I ever got first hand was a licking!” she muses as she mends a ratty hand-m-down dress from Lotta. “I’ve even got a second hand mother and slightly used dog.”

Unlike many female characters in 20s comics, Ella was not designed as a beauty…and she knew it. Her signature look came from a shingle bob haircut, a wall of black hair below the ears that combined with huge pie eyes to make for a good comic strip visual, an immediately identifiable lead character in the frame. Plumb was a serviceable cartoonist who got more polished and sensitive to the language of daily strips over the years. But Ella benefited most from Conselman’s prose, dominated by colorful metaphor and simile. “You’re as dumb as a jaywalker in Venice,” she jokes with the mailman. “My face is my fortune, which makes me just four dollars poorer than a bankrupt.” And, again, in a way that sets the strip apart from others, Conselman gives Ella this verbal creativity to enmesh us with her character as world-weary, knowing, insightful, often hard-boiled.

Ella soon runs away from her step family and encounters a gritty world of cheats, cranks and the occasional soft heats, only to fall back into her stepmother’ clutches. Ultimately, winning a beauty contest brings her to Hollywood and a path to stardom that soon crashes and sends our hard-luck heroine on years of mis-adventures, forever missing fame and fortune, and somehow always with an eye towards finding that runaway father.

There is an unusual pathos and richness to Ella Cinders. It was fairly popular in its day, spinning off into doll licensing, a prominent silent film only a year after the strip’s launch, as well as numerous big little books and comic books. Conselman’s imagination and lyrical style was clearly a driving force. He was an accomplished scripter of over 50 films as well as a writer of songs and plays. Plumb’s art also had its expressive qualities. He used Ella’s spindly body and physical postures to establish attitude and feeling, and his considerable background detail helped make mood and place a part of the strip’s aesthetic.

It strikes me that the nigh-forgotten Ella Cinders is woefully under-valued both in comic strip and pop culture history. I am hard-pressed to think of a female hero in film or literature that is quite like her, until we get to the assertive and fast talking ladies of 30s film – Stanwyk, Hepburn, Colbert, Lombard, etc. Gray’s singular Orphan Annie notwithstanding. As well, there is a hard-boiled/soft-hearted view of the American social margins here that feels more genuine than Gray’s, where the ferule artistry often felt crowded by the relentless platitudes. There is a resilience, world-weariness, even a hum of resentment and anger at the world that clearly found a sympathetic readership and made the strip a gem worth re-reading.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I found it interesting that you completely missed the connection of this cartoon and Colleen Moore’s movie “Ella Cinders”. It is quite obvious that this character is based on Moore. Anyway, great blog, and I am enjoying your entries!

Dan

Thanks for the note, Dan. But I am not sure I get the point? The film was a 1926 adaptation of the strip that launched the year before. Moore was famous before she was cast, but I don’t think her look or persona was unique. The shingled hairdo was one of the bobbed hairstyles coveted at the time. Moore was a solid choice to portray Ella, but I don’t see anything in Counselman or Plumb’s stories that suggests they based the character on Moore. But let me know if you have other sources. Thanks again.

Pingback: Flesh, Fantasy, Fetish: 1930s and the Return of the Repressed – Panels & Prose