The comic strip may not have originated in the US, but in the 20th Century it quickly became an uniquely American art form. This modest blog will track my personal 50 year passion for these panels and prose and how they accompanied Americans through the rapid-fire changes of the last century.

Who is this guy, and why is he spending his sixth decade on our planet doting on comic strips?

I come by the obsession honestly. My father was a commercial artist and ad agency creative director who did his freelance work at home. For the first seven years of my life, an artist’s drafting table was in my sister and my bedroom. The fluorescent desk lamp was our nightlight as Dad drew and did paste-ups long into the night. His cartooning skills were legion. He caricatured his car dealer clients into comic super-heroes in the back pages of northern New Jersey newspapers of the 1960s. I recounted this memory to the great “Real Life” cartoonist Stan Mack years ago and he captured it in one of his strips at MediaPost. And of course I read the funnies. Peanuts especially I memorized and recited. But I also floated in and out of B.C., Pogo, Steve Canyon, Mary Worth, The Phantom, among others.

But six books I encountered between the ages of 11 and 13 channeled my appreciation into devotion.

The Great Comic Book Heroes, Compiled, Introduced and Annotated by Jules Feiffer (Dial Press, 1965).

This may have been the earliest effort to reprint the seminal comic book heroes of the 1940s, from Superman to Plastic Man, Wonder Woman to The Spirit. Feiffer, who was a part of that history, taught me a lot. This was not hagiography. Feiffer knew that most of the art was bad and that the psychology beneath the comic book superhero represented a strange turn in the culture. “The advent of the super-hero was a bizarre comeuppance for the American Dream,” he wrote. “Horatio Alger could no longer make it on his own. He needed ‘Shazam.’ Here was fantasy with a cynically realistic base: once the odds were appraised honestly it was apparent you had to be super to get on this world.” Jeezuuus, I realized. You could think and write this way, even about the primal and poorly wrought areas of pop culture. And you didn’t have to make excuses for poor artistry in order to take pop culture seriously or appreciate its aesthetic qualities. Feiffer introduced me to the idea that one could write thoughtfully, critically and make cultural connections about pop culture.

The Ridiculously Expensive MAD (World, 1969)

This book taught me that in many respects the past was better than the present. Of course, at 11 I was a MAD magazine devotee. But this greatest hits volume introduced me to Harvey Kurtzman’s send-ups of super heroes and sent me back to reprints of his tenure. I realized that MAD was once a truly great and insightful magazine, that much of pop culture was based in childish premises, and that mass media often got worse over time rather than better.

The Celebrated Cases of Dick Tracy (Chelsea House/Bonanza, 1970)

I got this treasury of 30s-40s comic strip Tracy reprints for Christmas 1970, at age 12. I devoured it through New Years. Gould’s visual voice grabbed me then and continues to be my origin point in understanding the medium. I had been reading comic strips throughout my childhood, of course, but this book showed me that in many ways a previous era of strips had been richer, more explicit and gut-wrenching, more imaginative. The book reprinted key villains and adventures from the origin story through 1949. Watching Gould find his stride taught me how important visual style and cadence were to the aesthetic power of the medium. And Gould’s idiosyncratic graphics underscored the incredible individualism of this medium, how much the comics page embodied an enormous range – a democratic diversity – of worlds that were defined so efficiently in 3 to 4 panels a day.

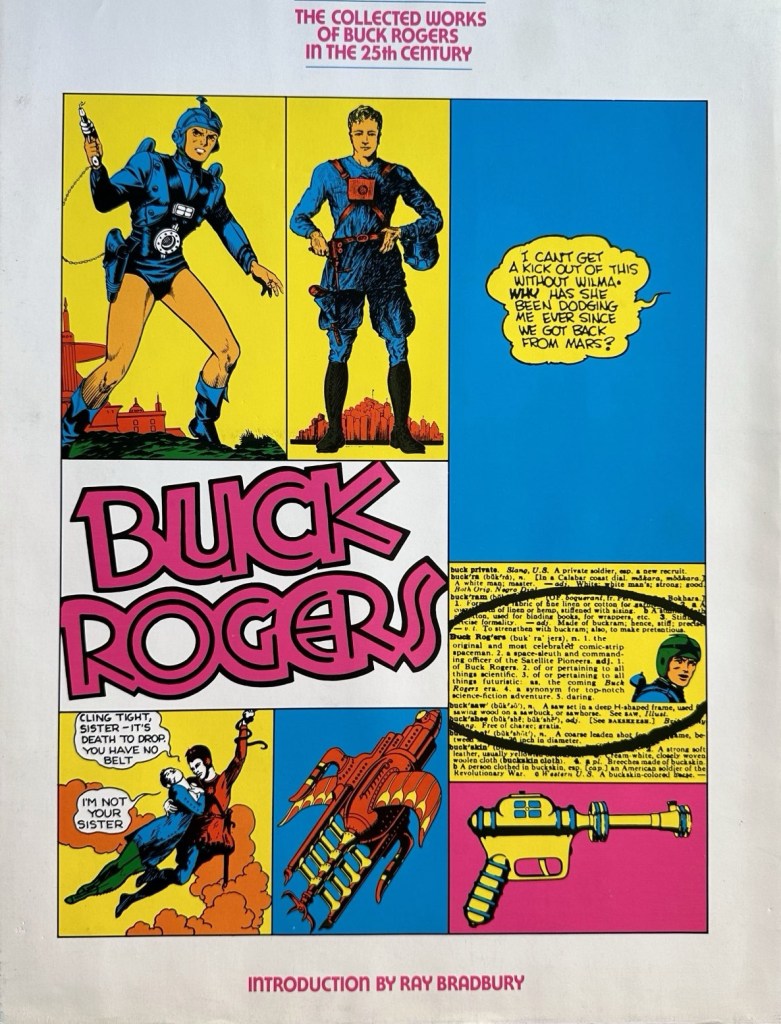

The Collected Works of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (Chelsea House, 1969)

This may have been the first oversized, weighty comic strip reprint ever done. Certainly, it was the earliest immersive trove of golden age goodness I can recall. It was too expensive for my 12-year-old self so I had to rely on repeated borrowing from the local library. I discovered the joys of retro-badness in Phillip Nowland’s stupid scripts and Dick Calkins wooden art, because they were salvaged by crazed imagination and a fetish for technology. I didn’t realize at the time that other, better artists were making the color Sundays more engaging. But this is the book that made me fall in love with reprints and the special charms of early sci-fi weirdness.

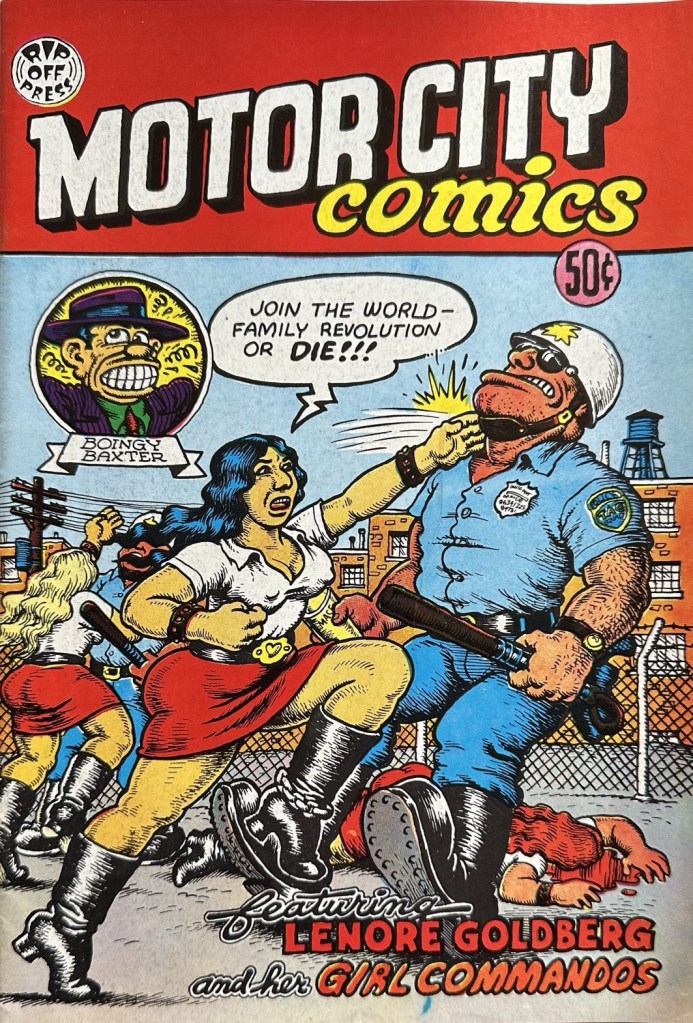

Motor City Comics (R. Crumb Productions, 1969)

I don’t. recall precisely when my hip Uncle in Greenwich Village gave my unhip Aunt in Wayne N.J. this underground classic that blew my mind. It found its way into my 11-year old hands, where Robert Crumb’s “Girl Commando” Lenore Goldberg introduced me to the concept of the blow job and the counter-culture. Motor City Comics also showed me early in my critical career how text+image could deliver unique emotional impact, make you think and feel differently, and color way outside the lines of newspaper and newsstand comics.

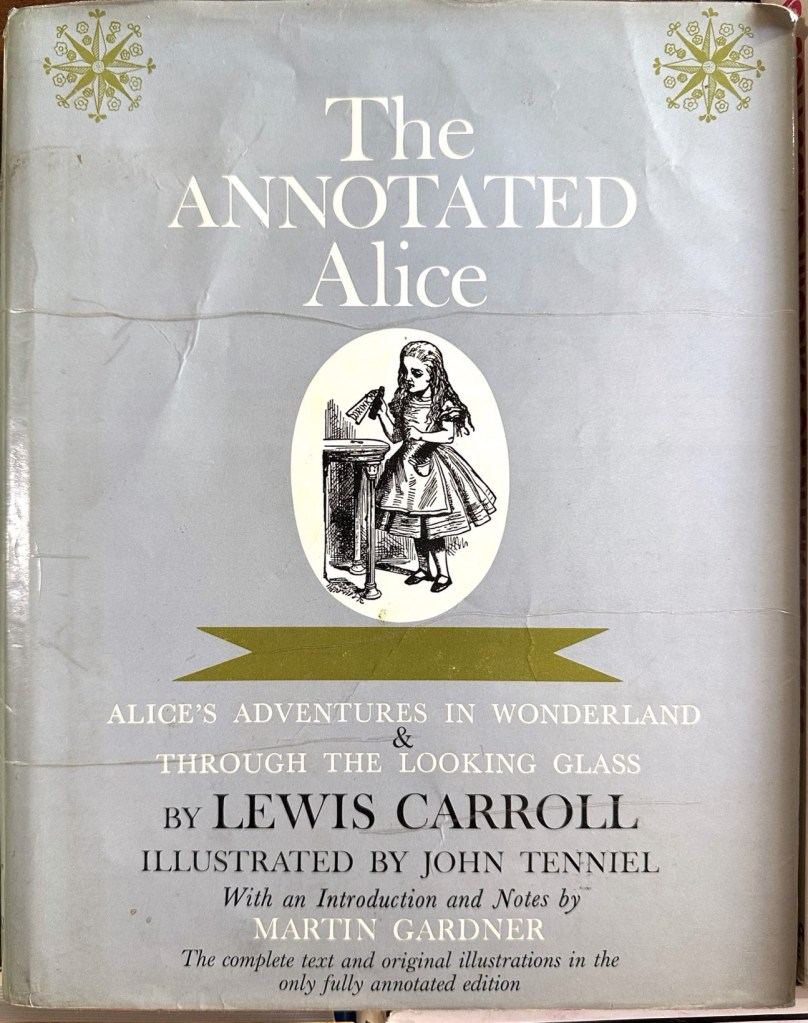

The Annotated Alice, by John Gardner (Bramhall House, 1960)

John Tenniel’s original illustrations for the Alice books grabbed me like no others in my childhood. They communicated the creepiness and real nightmarishness of Lewis Carroll’s world. Images can inform and even transform the reading experience. Carroll’s prose traded in the comedy of nonsense, and Tenniel hinted that the reality was more unsettling and darker than the words. And then when I discovered Gardner’s exegesis of the Wonderland and Underground books it underscored what I was learning from Feiffer (see above). These simple, childlike works could bear thoughtful scrutiny.

50 Years Later

Thus began a lifelong passion for pop culture history. I finished my doctorate in American Civilization at Brown in 1990, taught media criticism at University of Virginia (1988-95) and then left academia to become a media critic of the emerging Internet. This blog will try to combine all of those passions.

I am drawing from my accumulated collection of comic strip and pre-code comic book reprints. In recent years my wife and I were fortunate to find our 200-year-old stone dream house in Southeast Pennsylvania, where we dedicated one large room to creating the Panels and Prose Library. This site is designed for critical commentary and analysis of comic strip history.

PanelsandProse is a free and non-commercial blog. All editorial matter on this site is Copyright ©2020-2026 by Steven Smith. All Rights Reserved. All images of comic art are copyright by their respective copyright holders except those in public domain. If you hold the copyright to any image shown on this site and would like a copyright displayed, or believe the display is not fair use please contact me. Classic comic strip images are used here as part of educational and critical commentary within the “fair use” terms of US Code: Title 17, Sec. 107.

Dear Mr. Popeye,

I recently discovered your blog with your review of Trina Robbins newest book. I thought it would interest you that the American Weekly collection I had photographed was Bill Blackbeard’s own San Francisco Academy of Comic Art. I lived in SF at the time and Bill let me remove and photograph all the Edmund Dulac covers from 1924-1951. After his passing I learned that his entire collection was donated to the Billy Ireland CAM in Ohio. I am trying to contact them now to find out if further research into the American Weekly’s is still possible. I find their website obtuse, but computer research is not my forte. My eBook is listed on all the usual sites, but the larger JPG version is for sale on Etsy. If you are interested, please contact me for a free review copy.

Sincerely,

Albert S.

Pingback: Books That Made Me: A Panels & Prose Journey – Panels & Prose

Pingback: The Impaling of The Brow – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Calling Dick Tracy…Again: Shaking Up the Reprint Game – Panels & Prose