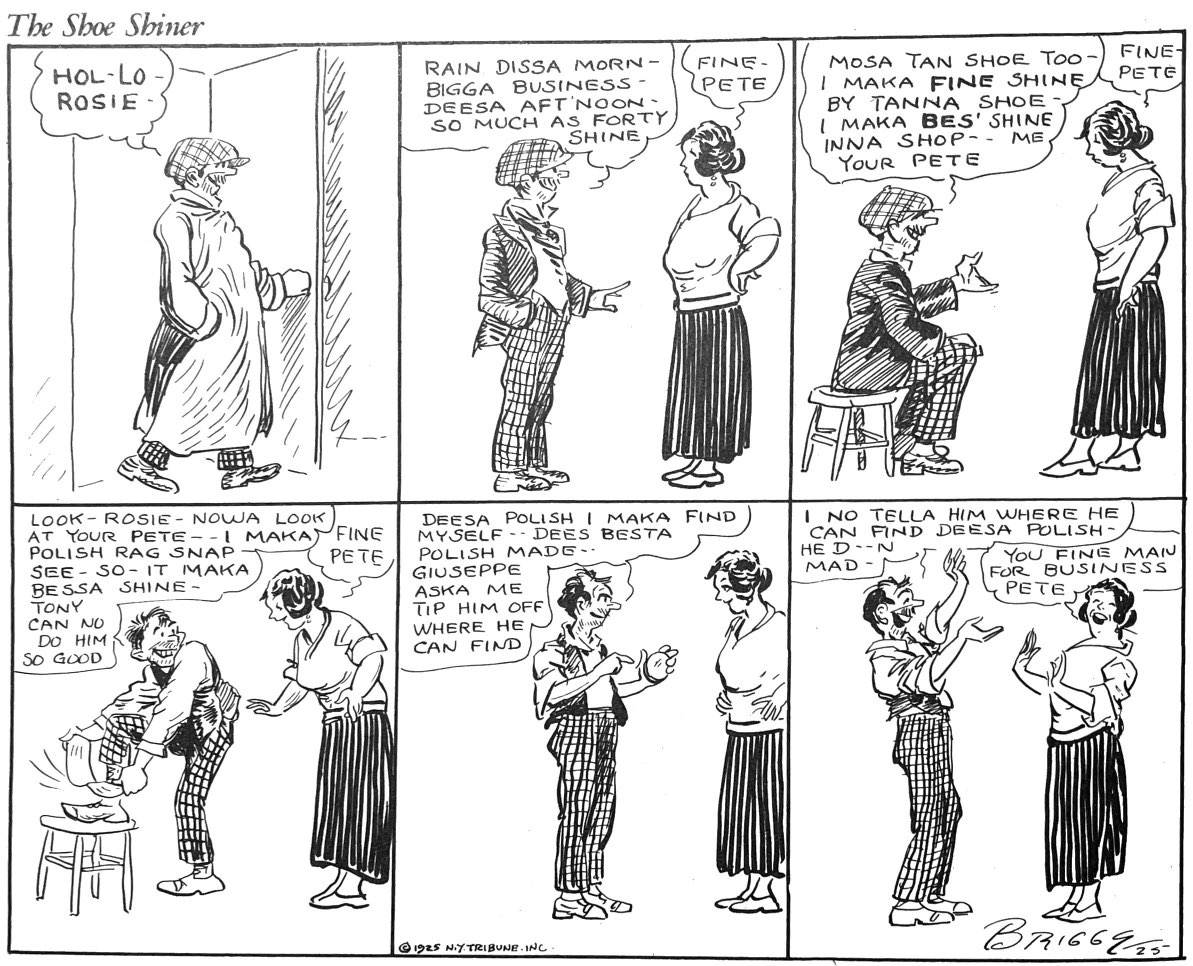

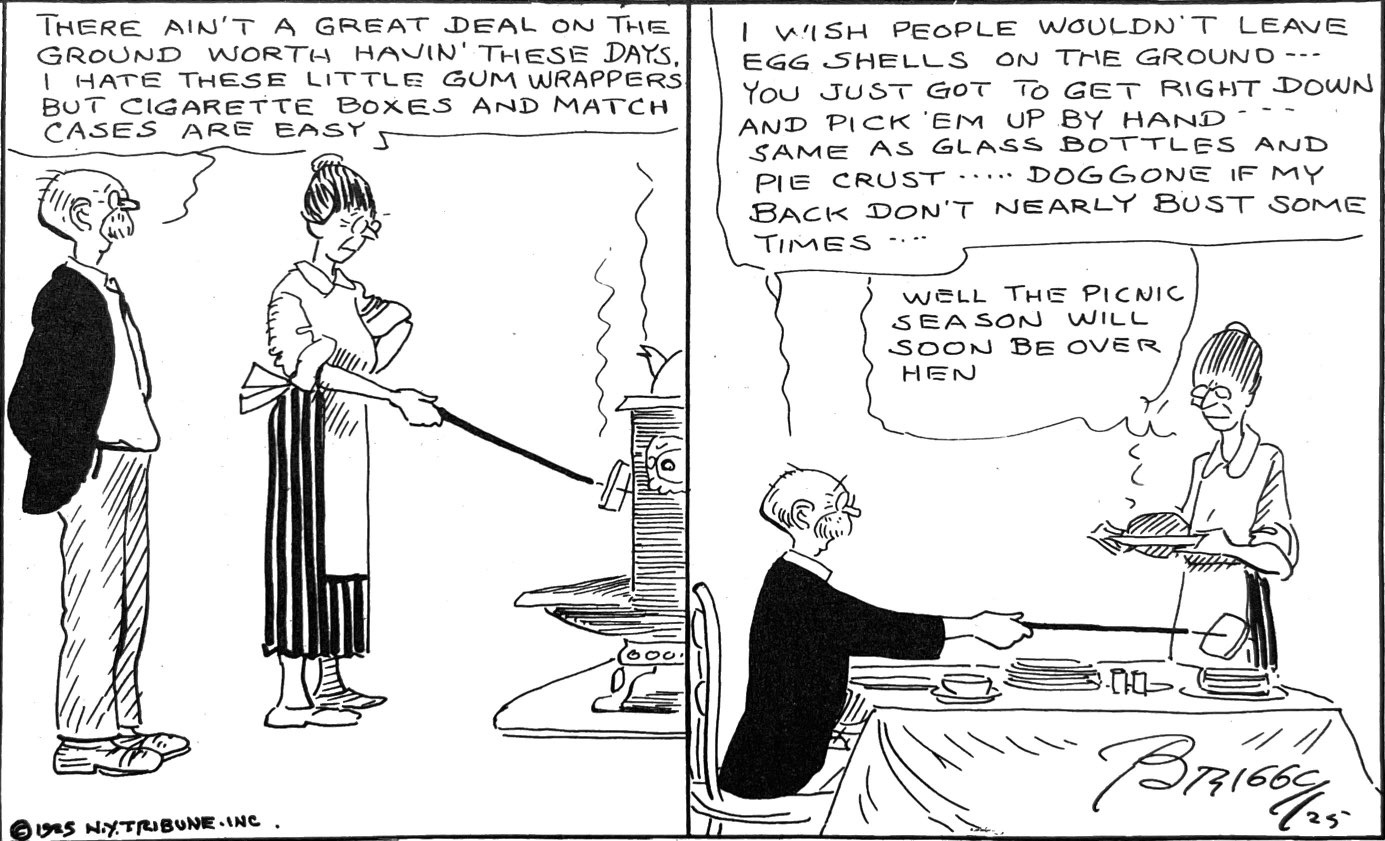

A shoe shine man enters his home after a long day’s work and boasts to his wife about his special talent for snapping his shine rag and using a better grade of polish. After work at a sign painter’s home, the practical artist extolls the superior quality of his brush and his unique mastery of curving letters. A park garbage cleaner muses on spearing newfangled gum wrappers and the challenges of cleaning up eggshells during picnic season. A soda jerk brags to his wife that his colleagues just can’t sling those mixed drinks as quickly as he. A street sweeper shows off to his wife the new brush with just the right heft and breadth for easier work, and then ponders his chances for promotion over “Jerry” who “is good at plain sweeping’ but he’s no good around telegraph poles.”

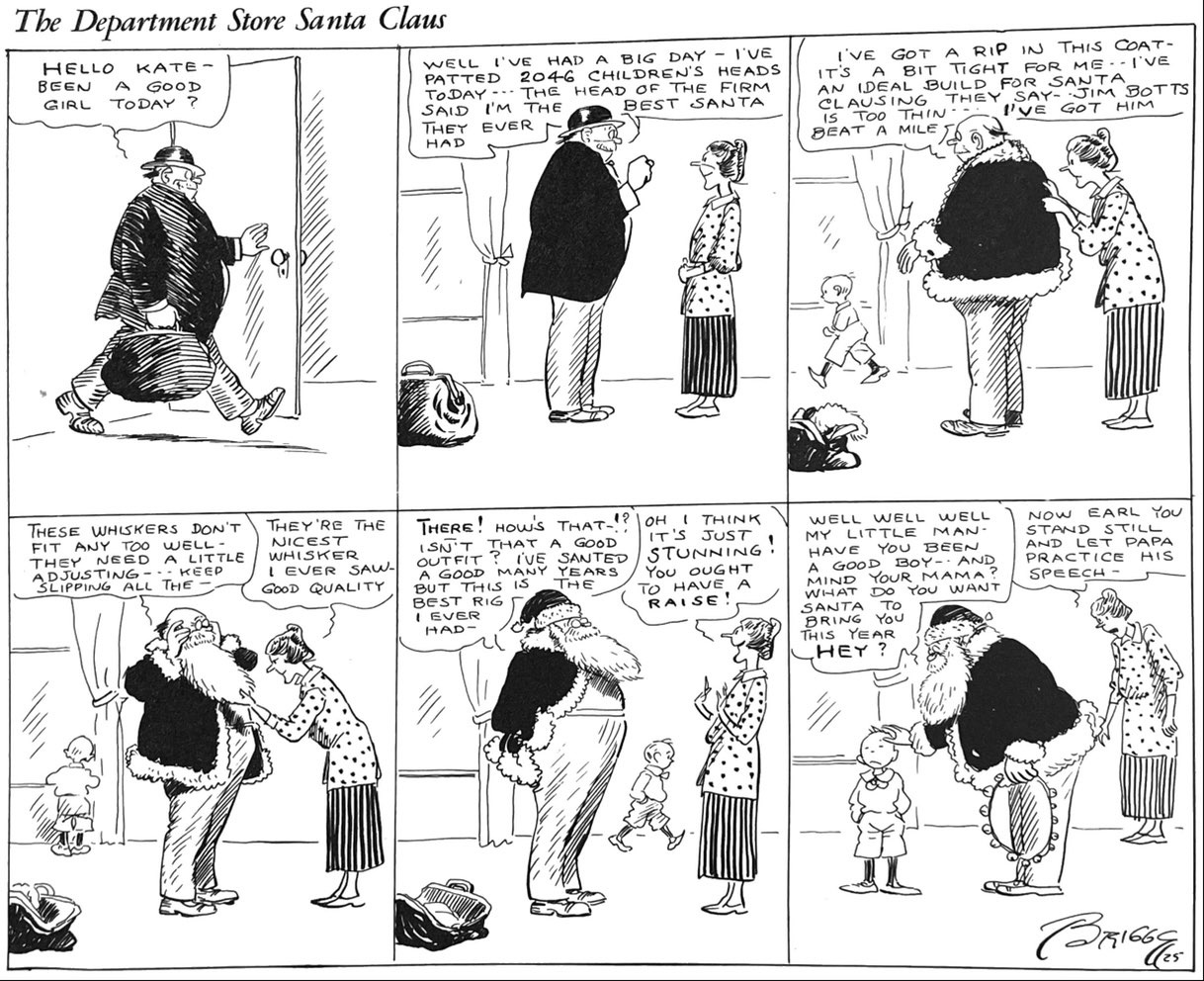

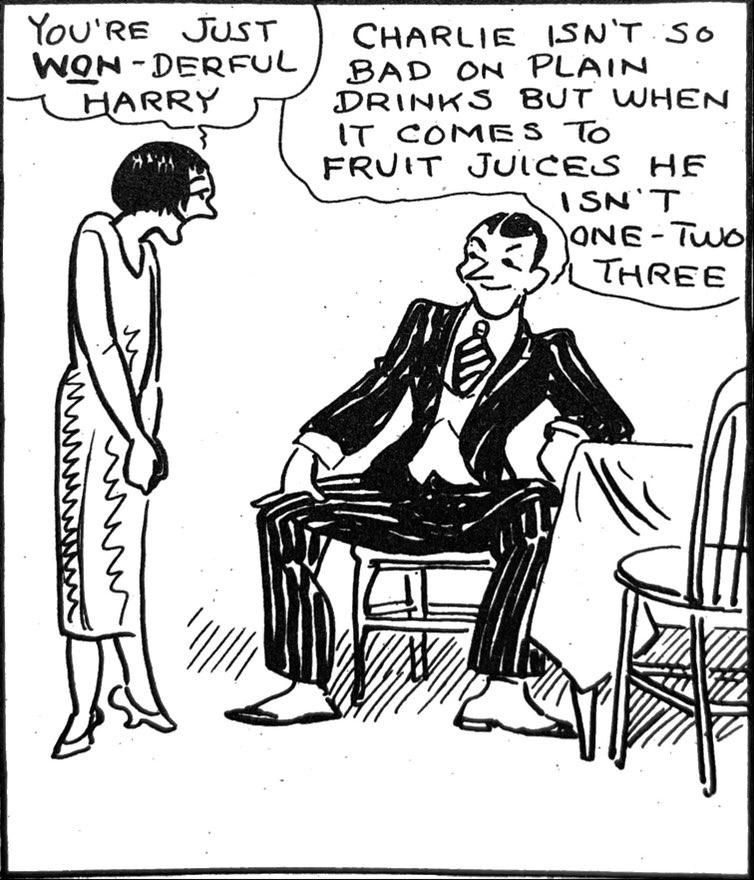

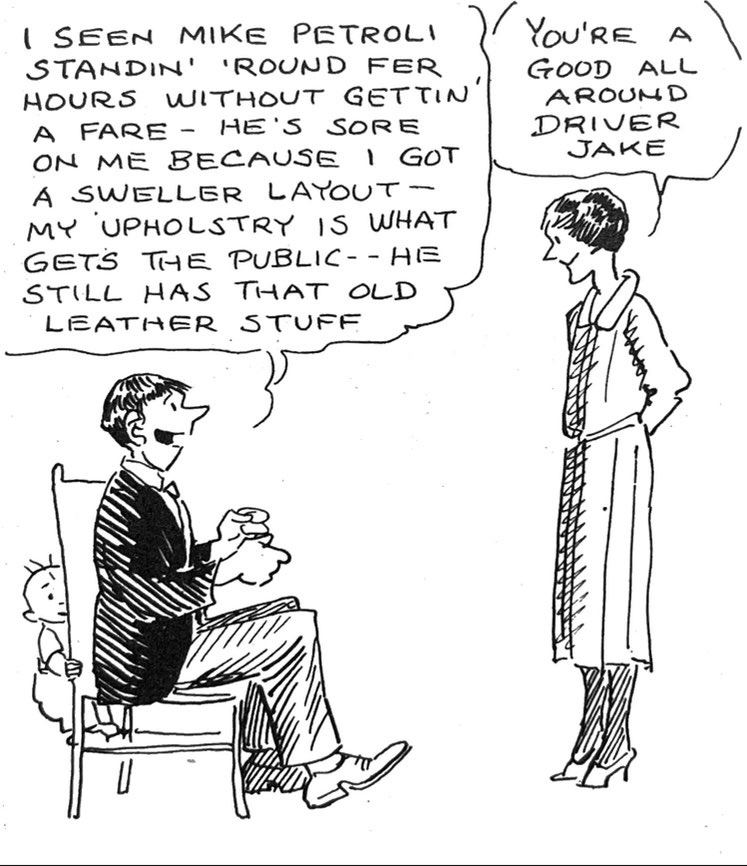

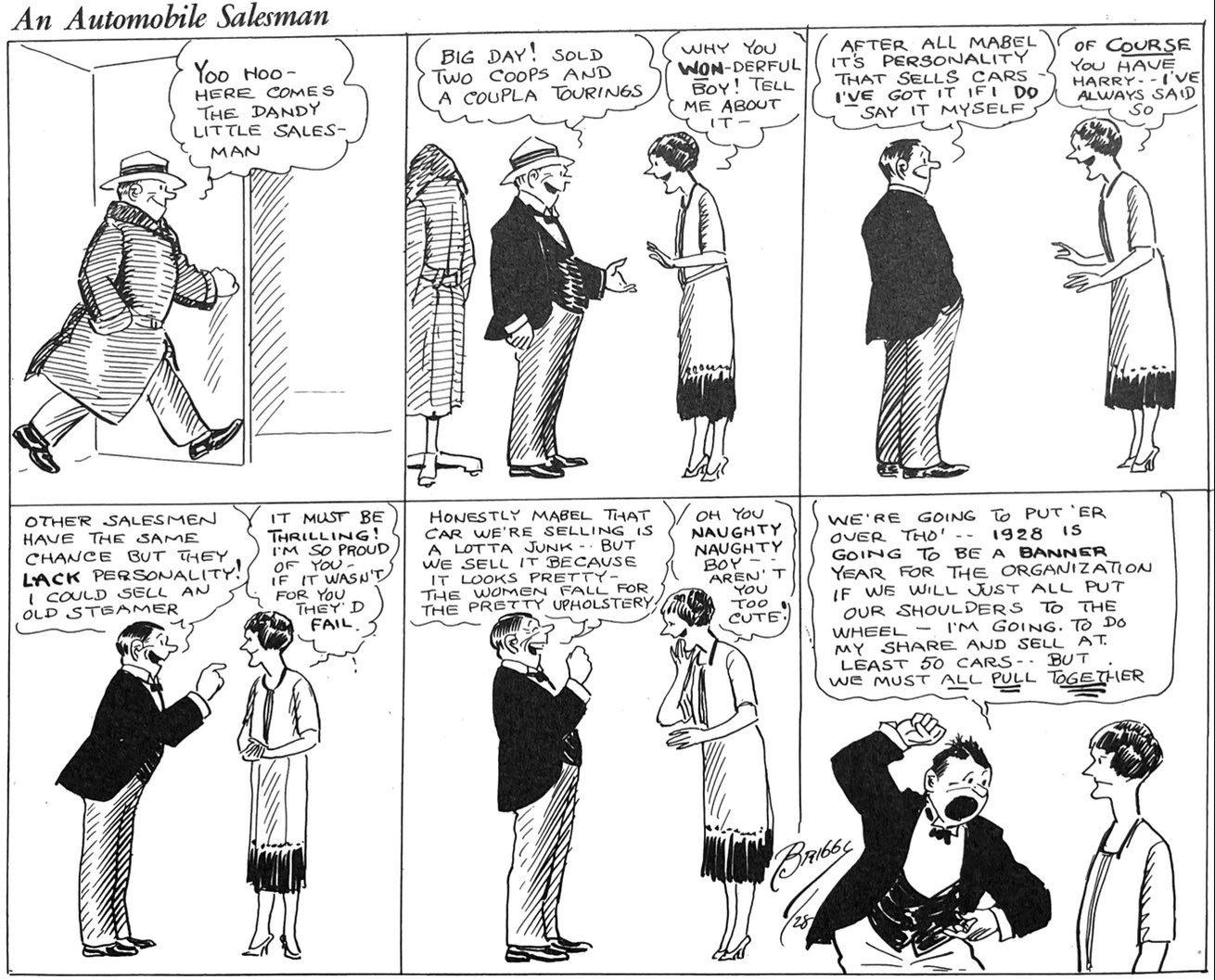

These scenarios of workingmen returning home at night and reflecting upon their craft was the conceit for Clare Briggs’ remarkable Real Folks at Home series of the 1920s. This was a deep dive into the nuances of pride, spousal support, small ambitions, respect for craft among the laboring classes for the most part. There were occasional forays into more vaunted professions like an orchestra conductor, opera singer, or baseball star. But largely Briggs was concerned with the hard-working manual laborers who may have been invisible to the white collar suburban classes to which many newspapers tried to expand their circulation after WWI. This was a regular celebration of the people who made towns and cities run, the dignity of work, and the native intelligence and thoughtfulness of “real folk.”

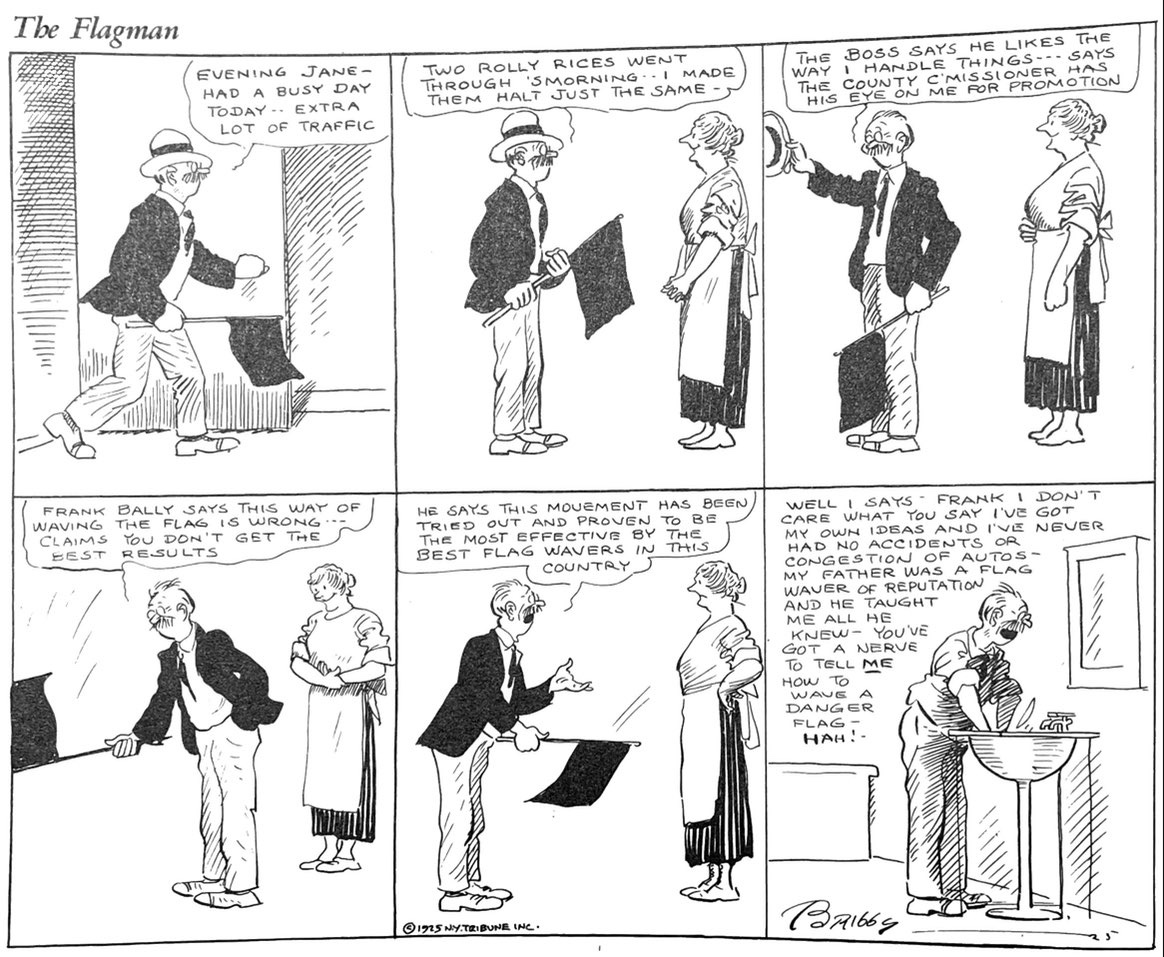

The Flagman embodies many of the themes Briggs explored in Real Folks at Home. Here a road crew flagman recounts the workday highlights to an admiring, attentive wife. Spousal support seems to be key to Briggs’ working class idyll, where wives celebrate their husbands’ skills, ratify their egos and lobby for them to apply for raises. This is quite different from the chronically bickering and distrustful Joe and Vi from Briggs’ own Mr. and Mrs. strip. But in Real Folks, the male menial laborer is king of his castle and hero of the workplace. Our flagman lectures his admiring wife on the latest controversy over flagging techniques and how he and his colleagues differ on which hand movement is more effective at controlling traffic. Across these strips Briggs transforms laborers into experts and craftsmen, masters of the brick hod, street sweeping, or road flagging. He invests manual labor with intelligence and discrimination. And, of course, there is male ego. In most of these strips, our blue collar hero compares himself to his less able fellows, the soda jerks who can’t handle mixed drinks quickly, the sweeps who don’t get around telegraph poles, the watchmen who make too few rounds. Real Folks at Home was a celebration of common man pride, ambition and dignity.

Clare Briggs (1874-1930) was among the best known, best-paid, and beloved of American cartoonists in the 1910s and 1920s. Historians often remember him as a master of the nostalgic slice-of-life panels of small town childhood (The Days of Real Sport, When a Feller Needs a Friend, Aint’ It a Grand and Glorious Feeling). He is also credited with pioneering the format of the daily strip with recurring characters in A. Piker Clerk (1904) at Chicago’s American. He was so popular among newspaper readers nationwide that upon his premature death in 1930, his publisher issued a seven-volume retrospective of his work, from which the images here have been scanned.

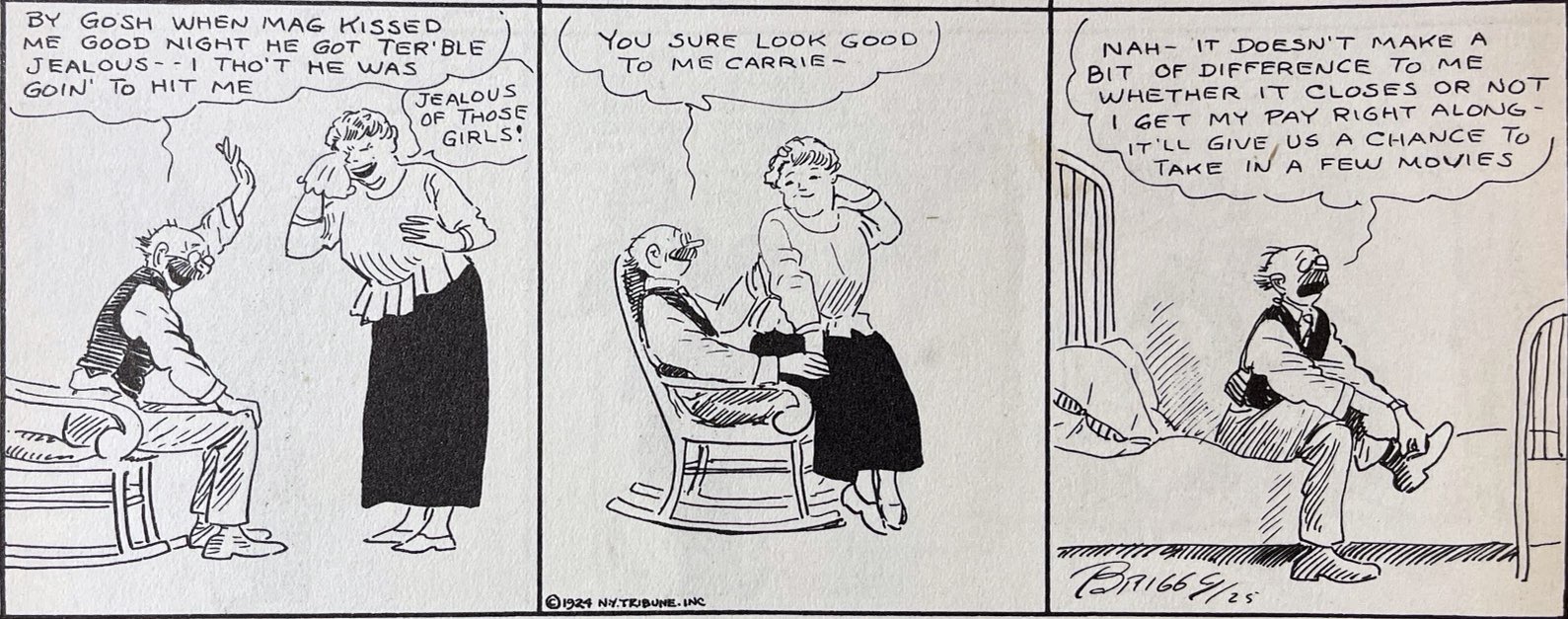

While his slice-of-life panels usually align him with fellow cartoonists like J.R. Williams and H.T. Webster, Briggs could bring a sharper and more satirical edge to his vision of modernizing America than some of his peers. His Mr. and Mrs. strip of the 1920s depicted the ongoing marital dysfunction of Joe and Vi, who often seemed genuinely to dislike and distrust one another.

Real Folks at Home ran counter to the 1920s trend towards situation comedy among the the rising suburban middle class. This series focused on the moment workingmen returned home. Sign painter, hod carrier, road flagger, night watchman, traffic cop, mailman, garage mechanic are among the professions Briggs explores. Sometimes, Briggs goofs around with the profession. the orchestra conductor conducts his wife’s singing responses. The tour guide and his wife bark conversation to one another through megaphones.

But the most interesting examples of Real Folks at Home are appreciations for the pride that everyday laborers take in their craft, the social insights and perspective their jobs give them, and how their wives feed their male egos regardless the profession.

There isn’t a whiff of condescension in Briggs’ appreciation of these workingmen (and a few working women). His key insight is in showing the native intelligence and self-respect of men who see the art and self-expression in what others regard as menial tasks. The flagman shows his wife the special twist of the wrist that makes for a more noticeable warning signal. The sign painter proudly invites his wife to come see his handiwork and skill with curved letters. The nightwatchman dotes over the quality and freshness of his lantern wicks. The garbageman bemoans the amount of food people waste. And spousal support is critical to Briggs’ idealization of working class heroism. There is also a social critique lurking beneath many of these strips, an alternative vision of modernizing, consumerist America from the perspective of the class that services the more affluent, often invisibly.

This is another great example of the unique aesthetic qualities of the comic strip form and the singular ways it contributed to the cultural conversation. Briggs focused readers’ attention on aspects of American life and areas of society that were as rich in meaning as they were overlooked. This is what art does; enlarges our perspective and our sympathies. In his pioneering work, The Comics (1947) Coulton Waugh understood the importance of Briggs, and it is a shame so few of his successors have. “It’s the idea that gets you,” he wrote of Briggs. “The hominess, the truth of it, the insight, the looking into so many tiny dramas, hopes, and frustrations, which no one else ever bothered with and which are utterly real.” The brevity and regularity of the newspaper comic strip were uniquely equipped to cast a social microscope on small moments writ large. Briggs turns that moment of the workman returning home each night into a contemplation of the dignity and creativity invested in all work, as well as its connection to identity, ego, marriage and more.

Pingback: “Papa Love Mama?”: The Quiet Desperation of Mr. and Mrs. – Panels & Prose

Pingback: The Democratic Genius of Clare Briggs – Panels & Prose