The great Clare Briggs (1875-1930) continues to impress me as perhaps the most under-appreciated figure in American comics history. He was by no means a distinctive stylist or draftsman of the sort that helps us better remember fellow greats like McCay, McManus, Herriman, Sterrett, King or Gould. But in the staggering range of cartoon series he conceived (When a Feller Needs a Friend, The Days of Real Sport, Mr. and Mrs., Real Folks at Home, Movie of a Man, Wonder What _____ Thinks About, among others) he demonstrated a range of human empathy, attention to emotional detail, and a social/class sensitivity that seems to me unmatched by any other American comic artist. Briggs was among the highest paid cartoonists of the 1920s, and widely known and beloved by audiences who were shocked at his premature death at aged 55 in 1930. His loss to the field was so deeply felt that his publisher issued a multi-volume memorial retrospective of his greatest work shortly after his death.

Continue readingTag Archives: Clare Briggs

“Papa Love Mama?”: The Quiet Desperation of Mr. and Mrs.

Clare Briggs’ contemplation of marital tension, Mr. and Mrs. (1919-1963) has always fascinated me both because of the harsh tenor of the strip itself and its source. When comics historians bother to remember Briggs (1874-1930) it is as quaint master of the nostalgic slice-of-life panels of small town childhood (The Days of Real Sport, When a Feller Needs a Friend, Aint’ It a Grand and Glorious Feeling). He is also credited with pioneering the format of the daily strip with recurring characters in A. Piker Clerk (1904) at Chicago’s American. But to contemporary newspaper readers in the 1910s and 1920s, he was among the best known, best-paid, and beloved of American cartoonists. His premature death in 1930 prompted both a single volume retrospective and a formidable seven-volume collection of his many strips.

Continue readingThe Working Class Heroes of Clare Briggs

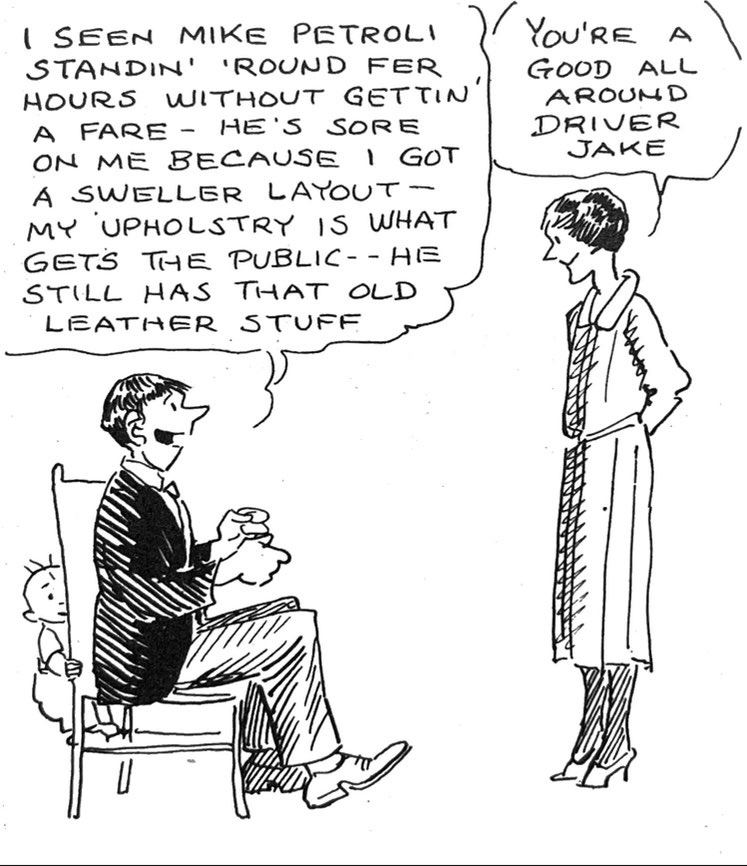

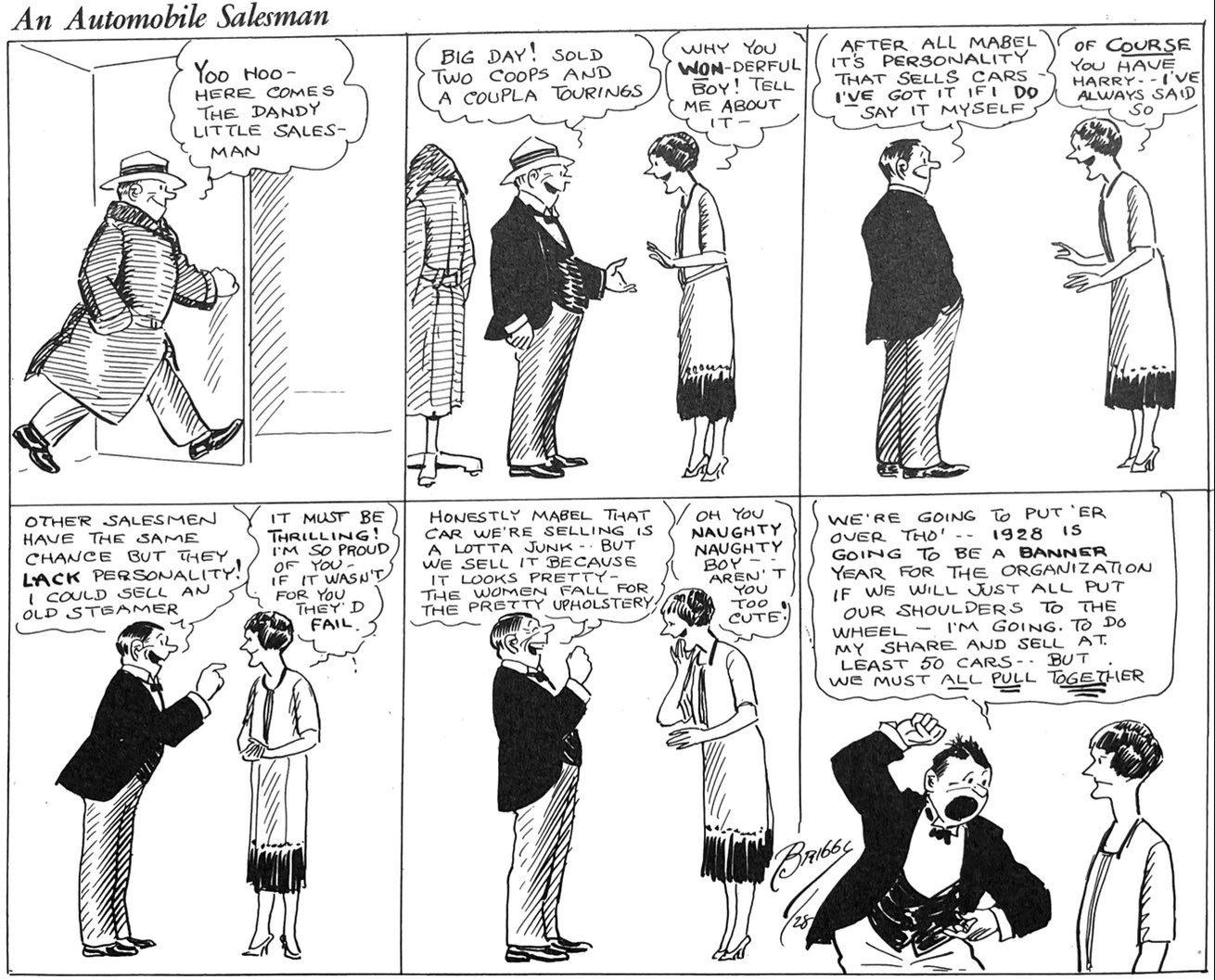

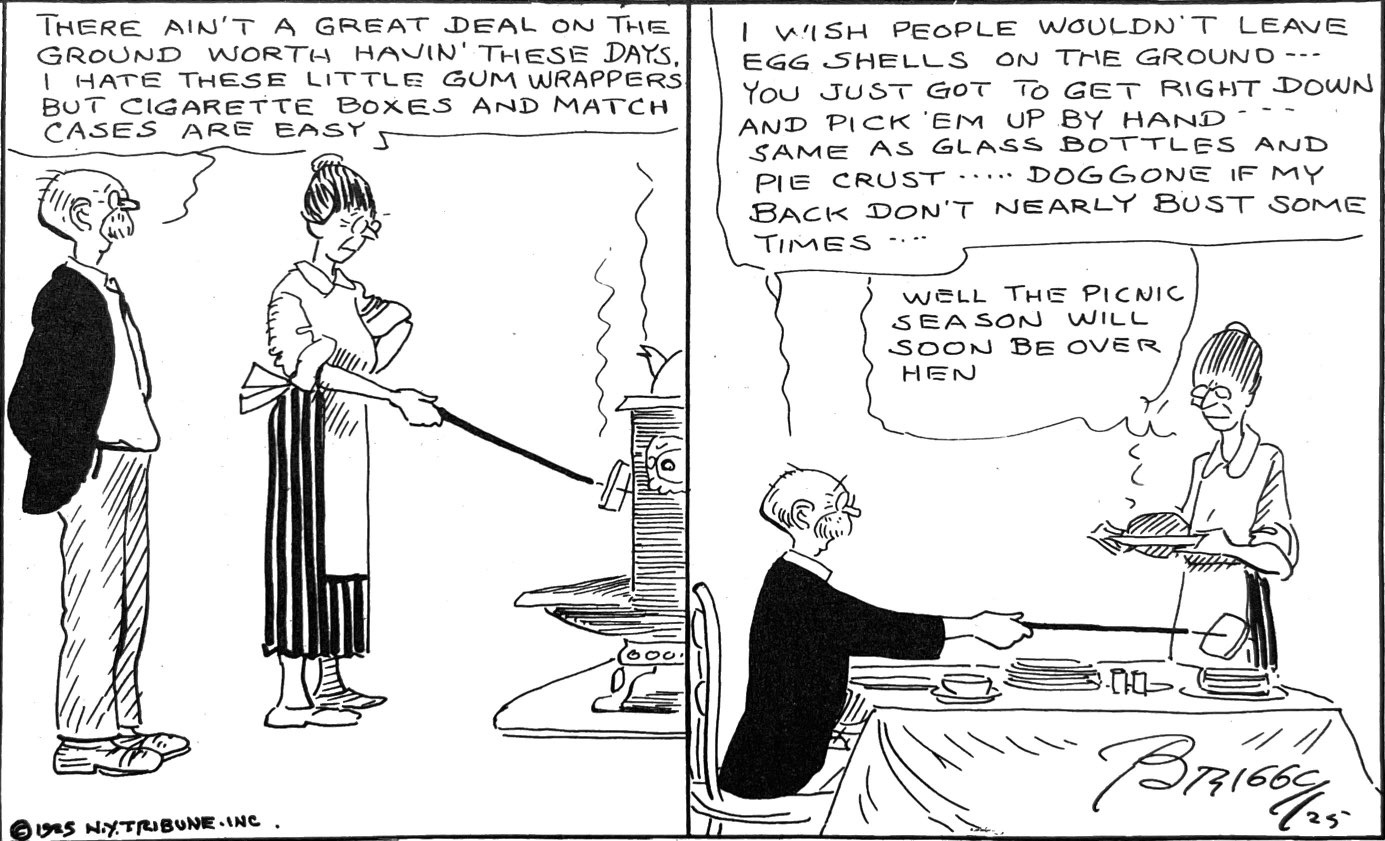

A shoe shine man enters his home after a long day’s work and boasts to his wife about his special talent for snapping his shine rag and using a better grade of polish. After work at a sign painter’s home, the practical artist extolls the superior quality of his brush and his unique mastery of curving letters. A park garbage cleaner muses on spearing newfangled gum wrappers and the challenges of cleaning up eggshells during picnic season. A soda jerk brags to his wife that his colleagues just can’t sling those mixed drinks as quickly as he. A street sweeper shows off to his wife the new brush with just the right heft and breadth for easier work, and then ponders his chances for promotion over “Jerry” who “is good at plain sweeping’ but he’s no good around telegraph poles.”

These scenarios of workingmen returning home at night and reflecting upon their craft was the conceit for Clare Briggs’ remarkable Real Folks at Home series of the 1920s. This was a deep dive into the nuances of pride, spousal support, small ambitions, respect for craft among the laboring classes for the most part. There were occasional forays into more vaunted professions like an orchestra conductor, opera singer, or baseball star. But largely Briggs was concerned with the hard-working manual laborers who may have been invisible to the white collar suburban classes to which many newspapers tried to expand their circulation after WWI. This was a regular celebration of the people who made towns and cities run, the dignity of work, and the native intelligence and thoughtfulness of “real folk.”

Continue reading