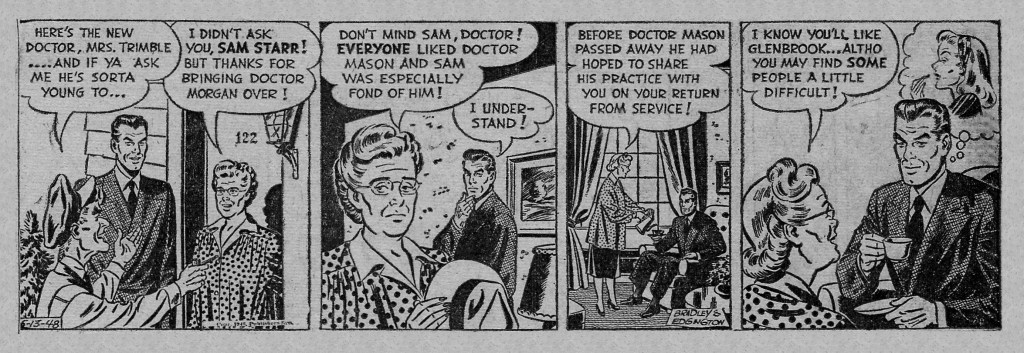

Remember when doctors were iconic pillars of respectability and authority in pop culture? Before alternative medicine? Before CDC missteps? Before drug company bribery? Before all expertise became “elitist conspiracy?” Remember Dr. Kildare? Ben Casey? Marcus Welby? And how about the most enduring of them all, Rex Morgan, M.D.? Launched on March 10, 1948, the doctor-driven soap opera was the brainchild of a psychiatrist, Nicholas P. Dallis, who wrote under the moniker Dal Curtis. His intent was to create a doctor hero who ministered not only to broken bodies but to overall mental and moral health. Young Dr. Morgan, apparently not long out of medical school, moves to the small town of Glenbrook to take over the practice of the burg’s departed, beloved practitioner. The strip was very much part of the psychological turn in American pop culture after WWII. Morgan represented that new generation of more enlightened experts of all things both scientific and emotional.

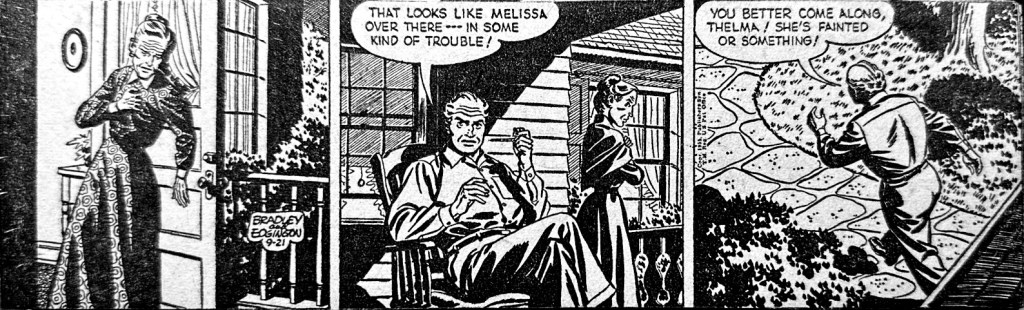

But at the same time, Rex Morgan M.S. rightfully remains a monument of 1950s iconography. For many years under the hands of main artist Marvin Bradley and backgrounder John Edgington, the strip had the bland realist style of contemporary advertising illustration. Characters showed minimal expressiveness; environments were just as pristine and inexpressive; houses, cars, furniture were just as generic; and any cartoonishness was saved for the offbeat minor players and comic relief.

And Rex himself was not the dreamy empath so much as the moral enforcer, a tough-lover who pressed his small town of class and gender-bound stereotypes to face facts and get it together. In fact the opening episode in 1948 finds newcomer Dr. Morgan scolding one of Glenbrook’s wealthy leaders for spoiling his teen daughter, who recklessly drives into a young boy. “Your daughter’s behavior merely reflects your failure as a parent” Rex tells J.J. Van Coyne within minutes of first meeting him.

Like most soaps and situation comedy in the post-war era, the moral center of the universe, normality itself, was in the suburban American middle class. The wealthy were often portrayed as victims of their own privilege, and the laborers as comic relief or emotionally bombastic “characters.” Both upper and lower classes always seemed to benefit from the better example and good advice of a solid middle class paternalistic touchstone like Rex.

As in most medical drama, Rex Morgan, M.D. appropriated an instructional role, if only to give it greater authority. In the opening episode a single day is spent illustrating a transfusion, for instance.

And while Rex Morgan M.D. may have had the look and emotional range of an illustrated high school health book, one of its strengths was educational. Dallis intended the strip to surface medical and public health issues, which over the years would include alcoholism, euthanasia, domestic violence and eventually AIDS.

But at its most unwittingly weird, Rex Morgan, M.D. finds ways to meld science and sex. Even as privileged hellion Toni Van Coyne lays back to offer a transfusion it is unclear from her upward glances whether Doc Rex is about to take her blood or just take her. The 50s gender politics of Rex Morgan are pronounced at every turn. Nurse June Gale is of course quietly in love with the doctor, and it proved to be on of the longest lived teases in comics history. Rex and June wouldn’t wed until 1995. But Rex appears to be surrounded by women who are enamored with him in one way or another. The supplicant woman craving Rex’s attention, touch, or validation is one of the strip’s dominant tropes. And throughout much of the 1950s, the strip found many ways to police the borders of acceptable feminine roles and behaviors. A 1955 sequence introduces a medical woman, Dr. Lea Layton, whose professionalism is expressed in a lack of humanity that Rex and the other women of Glenbrook somehow must correct. Predictably, Dr. Layton has daddy issues, an alcoholic father from whom she has estranged herself and in the process from her own emotions.

There are times when Glenbrook feels like an asexual harem for the good doctor and the strip feels is a kind of doctor porn. Our physician protagonist is the placid center of gravity in a cosmos of women who live in a stereotypical realm of unruly feeling and fetish to be dominated by Dr. Rex’s male authority. Sniping, competitiveness, jealousy, scheming among the many women who surround Rex drive the soapy emotional threads that drive the melodrama. seem to swirl. Rex himself, of course, is the superhero of post-WWII paternalism. Bland but dependably sensible, he is the scion of the male, scientific, bureaucratic complex. His cultural role is to assert the authority of medicine, expertise and male stoicism against the chaos not only of disease, but self-delusion and unchecked emotion.

Its run in the 1950s is interesting more as a cultural curio, an artifact of post-WWII return to normality than it is of narrative imagination or artistry. For that our time is much better spent with Alex Raymond’s Rip Kirby, Stan Drake’s The Heart of Juliet Jones, Leonard Starr’s On Stage or John Cullen Murphy’s Big Ben Bolt. Each took the social realist turn in American comics in much more interesting directions. But Rex Morgan was certainly popular, and its titular hero’s name became synonymous with the knowing, steady physician type. The strip brought social topicality to the comics pages. And culturally, the strip speaks to post-WWII culture’s investment in a set of core values: science, expert authority, middle-class morality, gender hierarchy, psychological normality. In 1950s comic strip America, the object of adventure was less about exploring new realms than about rationalizing a new vision of American status quo.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: They Had Faces Then: Close-Ups, 50s Photo-Realism and the Psychological Turn – Panels & Prose

Been slowly going through, and loving, your blog. I feel I have to defend Rex Morgan a bit. I’m a bit obsessed with the serialized “soap opera” comic strips, and Rex Morgan is interesting among them. One of the most popular in the genre (well, at least at its peak, I have no idea how many print newspapers it runs in now,) it also doesn’t get much love or respect by fans of the old serialized strips. Well, the soap opera strips rarely do in general (unlike adventure strips) but at least a handful of them get some love due to their arts–Stan Drake’s work in Heart of Juliet Jones, or Alex Kotzky’s art for Apartment 3-G’s first few decades (interestingly, another strip created by Rex’s Nick Dallis.) And Nick Dallis, apparently after meeting Mary Worth’s Allen Saunders, basically took the then-current Mary Worth format and turned her into a young(ish) doctor–as he would with the titular character of his subsequent Judge Parker and, umm, the Professor in Apartment 3-G (OK, only kinda…)

Still, having made my way through decades of Rex Morgan over the years, I think it’s a better strip than it’s generally given credit for. The art is solid and occasionally great, and there’s genuine skill in how Dallis used the strip to get medical information out there, while never diverging from the soap opera melodrama.

Hey, thanks for the note and for reading. I know I was being hard on the old Doc here but I am with you on how compelling some fo the soap strips were, especially On Stage and Juliiet Jones. Apt. 3-G was quite good. I would like to see a reprint of those. Judge Parker is another of the great-white-father soaps I want to dig into as well. Thanks for reading and commenting.

BTW, how have you accessed the full run of Rex Morgan? I am always interested in finding good sources of strip runs.

Thanks for your reply! Honestly, because this post was so old, I didn’t expect a reply, or I would have gone over what I wrote more carefully :P

I admit, one thing that does interest me about the soap opera strips is I’m interested in serialized storytelling in general, and specifically the serials that targeted a stereotypically more female audience—from the 1860s British phenomenon of sensation serials, to American daytime radio and TV soaps. It’s interesting, in an interview with Mary Worth’s Allen Saunders I found from the 1970s, he says that the slow death of soap strips has a lot to do with the rise in popularity of TV soaps (which in the 1970s for the first time started picking up a young, especially college age, audience) and complained that the syndicate had too many restrictions on storylines they could do—one example he used was apparently being told not to feature a Black woman as the lead in a new storyline. I wonder about that—while daytime soaps are notoriously slow, still, it’s very different to escape into a 30 minute (and soon, 60 minute) TV program each weekday than to read a three panel (and soon, two panel) comic strip for 15 seconds a day. However, I do see a similarity now in that the few remaining daytime soaps on US TV are really a shell of what they were at their peak—not just with lower budgets, but also with writing that is less willing to push boundaries (historically soaps were known to tackle subjects, like abortion and gay issues, before primetime American TV would) and a far more rushed production model (due to budget, soap operas now never even have a full dress rehearsal before they shoot.) Which reminds me in many ways of the current state of the few remaining soap opera comic strips (my grandma was shocked to find out recently that Mary Worth is still running, though it hasn’t been in the paper she reads since the mid 90s.)

But I admit, a perhaps sick part of me finds their decline fascinating… Leonard Starr was smart to move to Annie from Mary Perkins and leave it at (pretty much) at its late 70s peak. Juliet Jones and Apartment 3-G were not so lucky—but I find Juliet Jones’ final decade, from 89-99 when Drake left, but Elliot Caplin remained as writer, with Frank Bolle taking over the art, kinda fascinating. It really lost any sense of identity—the final storyline in fact ends with a cliffhanger with Eve and Juliet in a plane that has just been high-jacked, not the type of story you would once associate with the strip. Bolle was also the artist for the final 15 years of Winnie Winkle which ended in 1996 (and actually had his friend Leonard Starr ghost writing for most of that chunk,) and most infamously was the final artist for Apartment 3-G, whose final years were so surreal, so awful, in both art and writing, that it was obvious no one at the syndicate seemed to even be reading it anymore… (Bolle of course once was a good artist, but by the time he, for some reason , started drawing everyone wearing turtlenecks, there’s a steady, and sharp decline in his work on these story strips from month to month…) The decline in Apartment 3-G ;s art seemed especially depressing just because, I gather from a 1989 interview with Kotzky, Nick Dallid actually sought him out for Apartment 3-G in 1961 because he knew his newest, third strip should distinguish itself with art that did compete with Juliet Jones (and I assume Mary Perkins and other photo-realistic strips of the 1950s.) Rading the first couple of years of 3-G, Dallis actually seems a bit out of his element without having the legal or medicine frameworks of his earlier strips—in a short time span he seems to basically repeat the same basic scenarios for each of the three women over and over before finally branching out (Kotzky said after a few years he was often involved in the overall plotting. Looking at the current state of Judge Parker, Rex Morgan, and Mary Worth, which just sort of now exist, but interestingly are taking different approaches to their stories (Judge Parker currently seems keen to tell big, espionage filled storylines that never have any resolution, while Rex Morgan goes out of its way to never have anything melodramatic or soapy, and Mary Worth just does… whatever it’s doing. I would chalk this up to the fact that there just isn’t the market for doing high quality newspaper continuity strips anymore—except we’ve had recent exceptions like the new run of Flash Gordon which I think is as good as that strip ever has been.

I managed to read most of the Rex Morgan run (along with a few others) in a few different ways, and over many years. I had a friend with a newspapers dot com account who was clipping and saving all the scans (a lot more work than I was willing to do), and a few sites like Comics Kingdom hosted a lot of the vintage years (especially for Judge Parker) along with everything since 1996 or so. Some other strips are more elusive partly because by the 1980s they didn’t run in too many papers—like the last two decades of Juliet Jones… I would happily buy more collections, but I understand why these strips aren’t really collected (Classic Comics Press did a great job with Mary Perkins of course, but after four volumes stopped their Juliet Jones editions—which originally had the ambitious goal of collecting all of Drake’s run—due to lack of sales.)

There is one really good resource that you might not be aware of, by blogger MarK Carlson-Ghost. He has detailed write ups about most of these strips (oddly missing Juliet Jones and Mary Perkins) covering basic storylines for each year, character appearances, and some historical details and criticism. https://www.markcarlson-ghost.com/index.php/category/comicstriphistory/