Like its eponymous heroine, Dale Messick’s Brenda Starr strip had to conquer the systemic sexism of the newsroom to make her mark. It launched in 1940 in constricted, Sunday-only syndication under the skeptical stewardship of New York Daily News legend Captain Joseph Patterson, after he had rejected Messick’s multiple submission for female-led adventure strips. According to lore, Patterson was unabashed in dismissing women in cartooning, claiming to have tried and failed with them in the past, “and wanted no more of them.” Messick’s samples were salvaged from the discard pile by Patterson’s more open minded assistant Mollie Slott, who helped the artist rework her ideas to feature an ambitious and dauntless female reporter. The artist was acutely aware of the gender deck stacked against her. Born “Dalia” Messick, she deliberately adopted the androgynous “Dale” to help get her strips considered more seriously. Slott convinced thge reluctant Patterson to give this red-headed firebrand and Rita Hayworth lookalike a try. History was made.

Brenda Starr was not the first strip to feature a female lead, nor the first drawn by a woman. Messick had been preceded by the likes of Rose O’Neill (The Kewpies), Grace Drayton (Dolly Dimples), Nell Brinkley (Bright Eyes), Ethel Hays, Gladys Parker (Mopsy), Jackie Ormes (Torchy), among many others who have been woefully underrepresented in the standard comic strip histories and anthologies. And of course there has been a range of female comics leads drawn through the male gaze: Ella Cinders, Tillie the Toiler, Connie, et. al. Frank Godwin’s Connie is the clearest progenitor of Brenda Starr. This heroine of an adventure continuity strip, demonstrated her competence in a range of professions, from movie star to pilot. But in Brenda we had an assertive careerist and adventurer, and one who called attention to the sexist micro-aggressions designed to contain the “fairer sex.” In the inaugural strip from June 30, 1940, Brenda recoils from the “sissy stuff” notices she records at the newspaper and the patronizing asides from male colleagues. The red-haired “hurricane” is saddled with a seemingly impossible assignment that seems to set her up to fail.

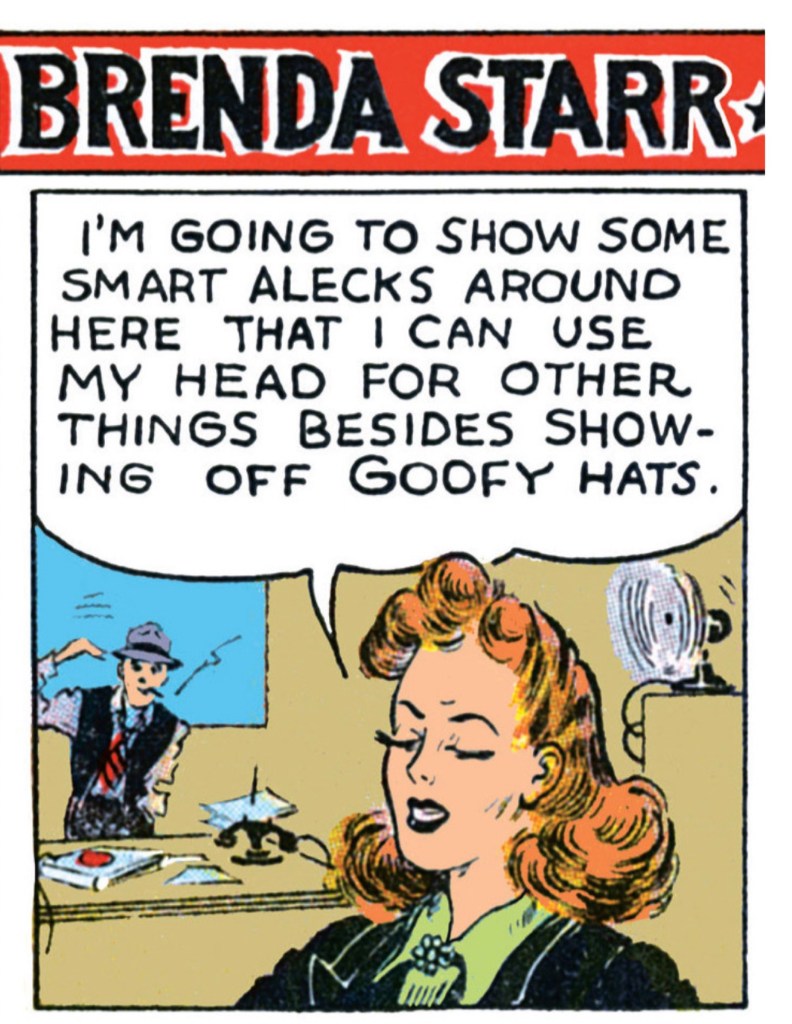

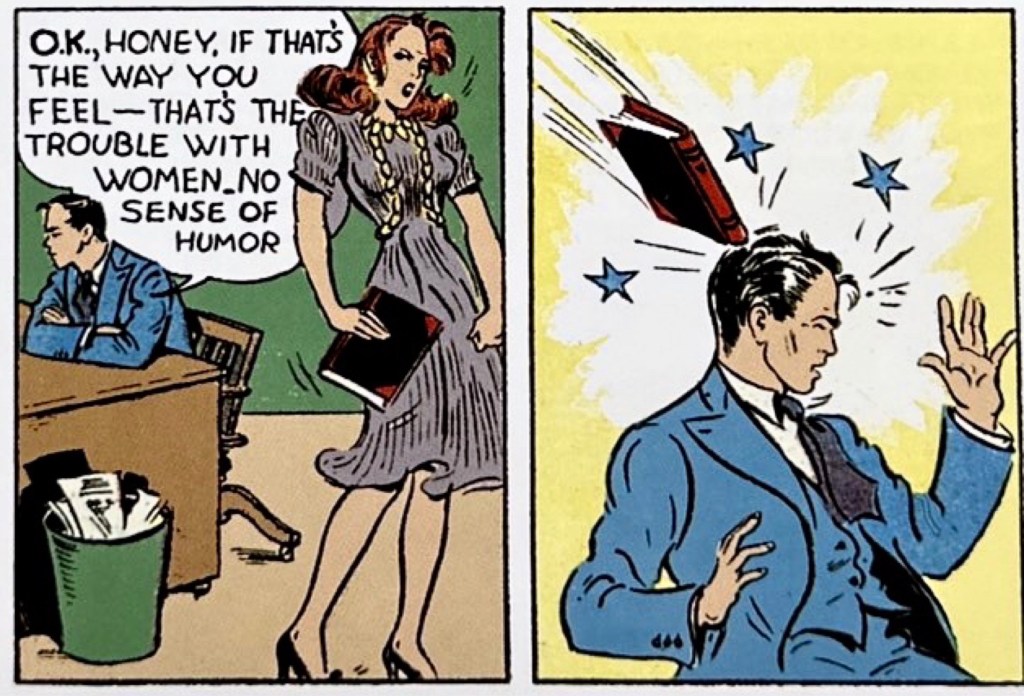

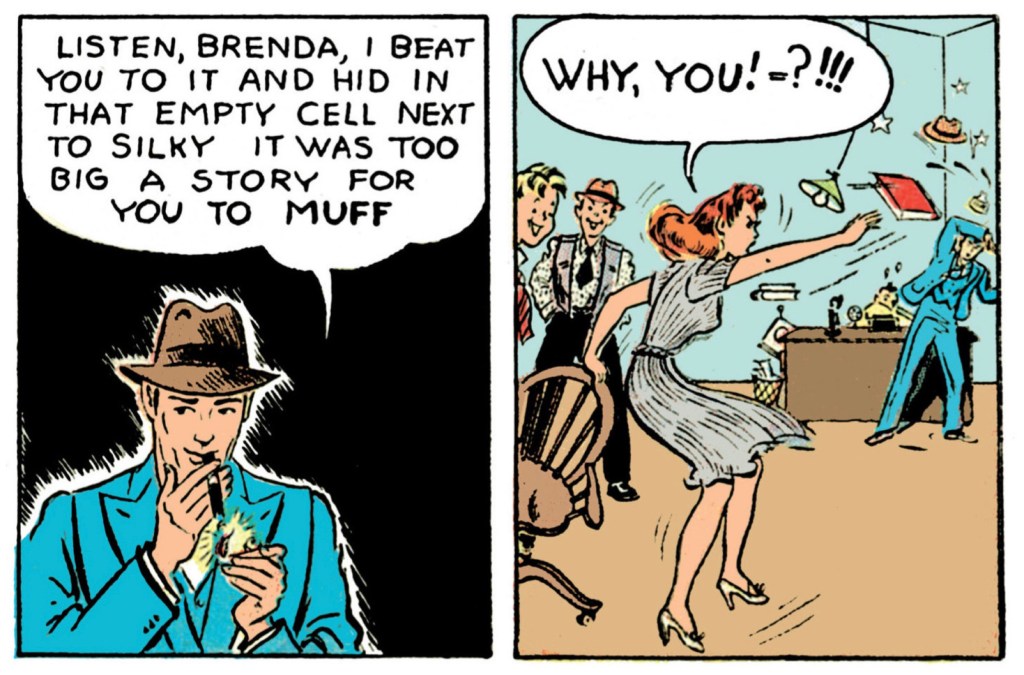

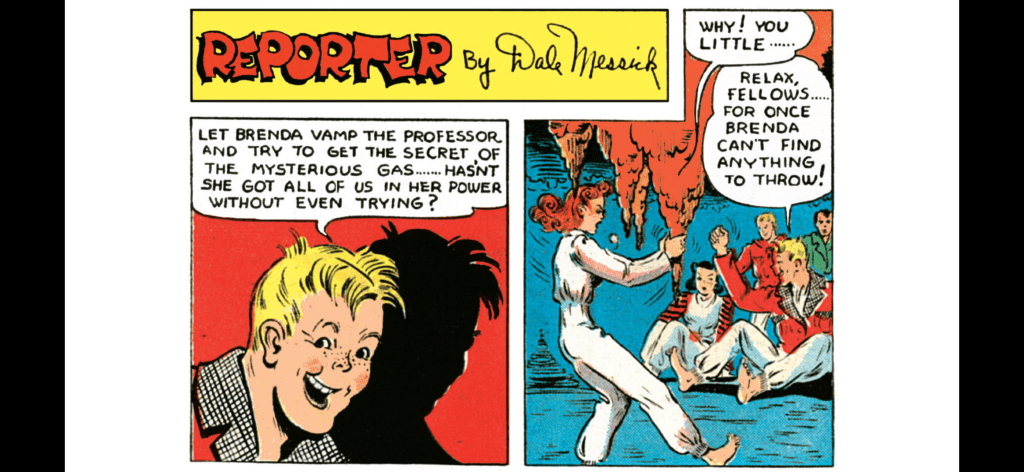

Women quickly embraced the strip, which not only had a strong heroine, but took a zany, imaginative path through a wide range of genres and offbeat characters, from murder mystery to romance, mad science to exotic international adventure. A daily strip was introduced in 1945, and Brenda Starr soon joined the pantheon of modern pop culture icons. Within the constraints of 1940s America, Brenda was closer to a feminist than one would have expected from the back pages of 1940s American newspapers. More than a hot head reporter determined to land a scoop, she literally took aim at the condescending men in her midst. In the first year of the strip, she was known for responding to sexist put-downs by tossing any found object at her co-workers’ noggins.

Depicting a career-focused heroine winning at a traditionally male job became enormously relevant soon enough. A year and a half after Brenda Starr started tossing books at patronizing colleagues, America was thrust into a dual-front war that diverted millions of the nation’s working men overseas. 1941-1945 was a critical “Rosie the Riveter: period in feminist history, as women took on industrial, managerial and executive jobs that would have been unimaginable earlier. For a brief, shining moment, if only for expediency, America seemed able to loosen the patriarchy. The early years of Brenda Starr spoke directly to the zeitgeist.

In fact, the Brenda Starr strip extended its liberated gender dynamics into an overall inclusiveness that was rare in most American strips. Fellow pop culture blogger Mark Carlson has studied the full range of Brenda Starr much more thoroughly than I. His comprehensive timeline and analysis of the full run of the strip calls attention to Messick’s inclusion and normalization of Black characters Siberia and Dusty Rose.

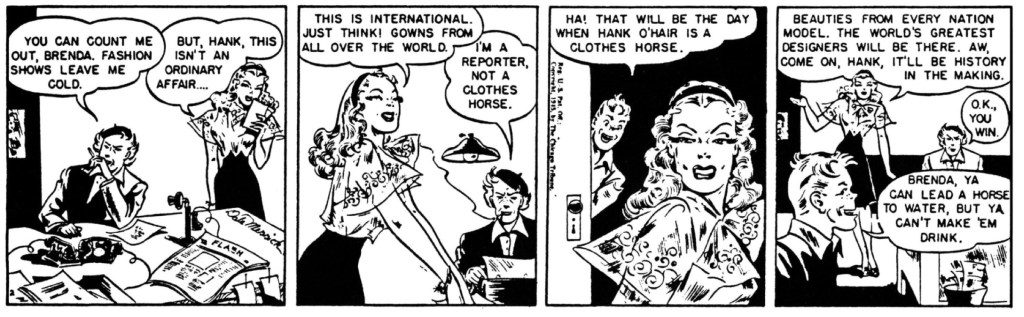

Which is not to say Messick and her strip transcended the very cultural stereotypes they seemed to be challenging on one level. Even in the first storyline in 1940, Brenda makes liberal use of her feminine tools, forcing a good cry to get a source’s sympathetic cooperation. While the men around her are often boyish or hapless, Brenda’s relationships with female colleagues like the rival Daphne can devolve quickly into mean girl sniping and even the occasional “catfight.” In fact, Brenda’s two genuine girlfriends are crafted out of sad tropes designed to highlight our heroine’s famous beauty and attractiveness. You could argue that her fellow reporter “Hank O’Hair” may be a refreshing early example of a thinly veiled lesbian comic strip character. But Messick throws every unfeminine butch trope she can get her hands on: masculine nickname, close cropped hair, side-slung cigarette in the lips, mannish suits and an allergic reaction to any “feminine” topic. Eventually Hank marries, of course, but apparently it came in response to readers’ trepidation. In a 1974 interview, Messick recounted that Hank was patterned after a reporter “I knew in New York, rather a masculine gal. But I got hundreds of letters saying people thought Hank was a lesbian and to keep her away from Brenda. I finally had to get her married and have a baby.” (cited in Caitlin, “Lovers, Enemies and Friends: The Complex And Coded Early History of Lesbian Comic Strip Characters,” Journal of Lesbian Studies, Vol. 22, No. 4).

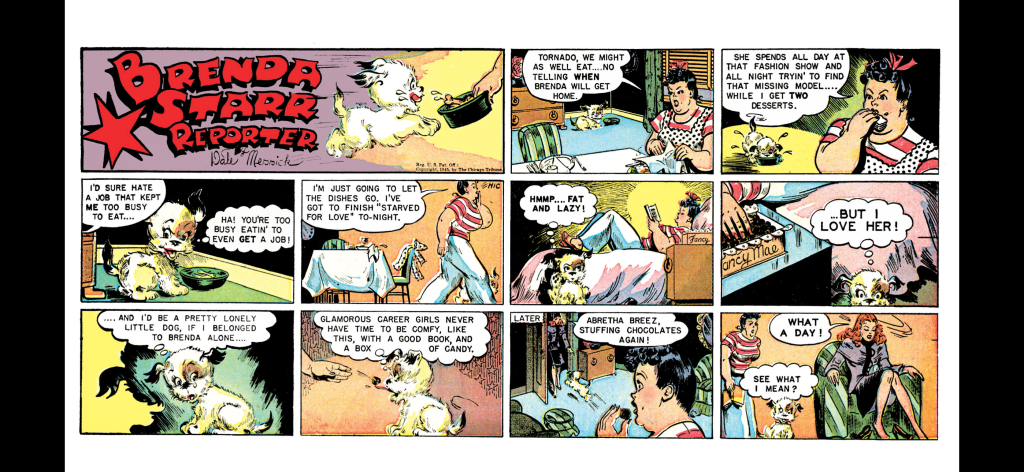

In fact, for a strip that famously broke a major gender barrier, Brenda Starr spends an inordinate amount of time policing the boundaries of traditional femininity. For instance, Messick uses good old fashioned fat-shaming to de-feminize Brenda’s other bestie, cousin Abretha Breeze. Abreatha is subjected to all forms of contempt for her weight, even from Brenda’s pup, tornado in the strip below.

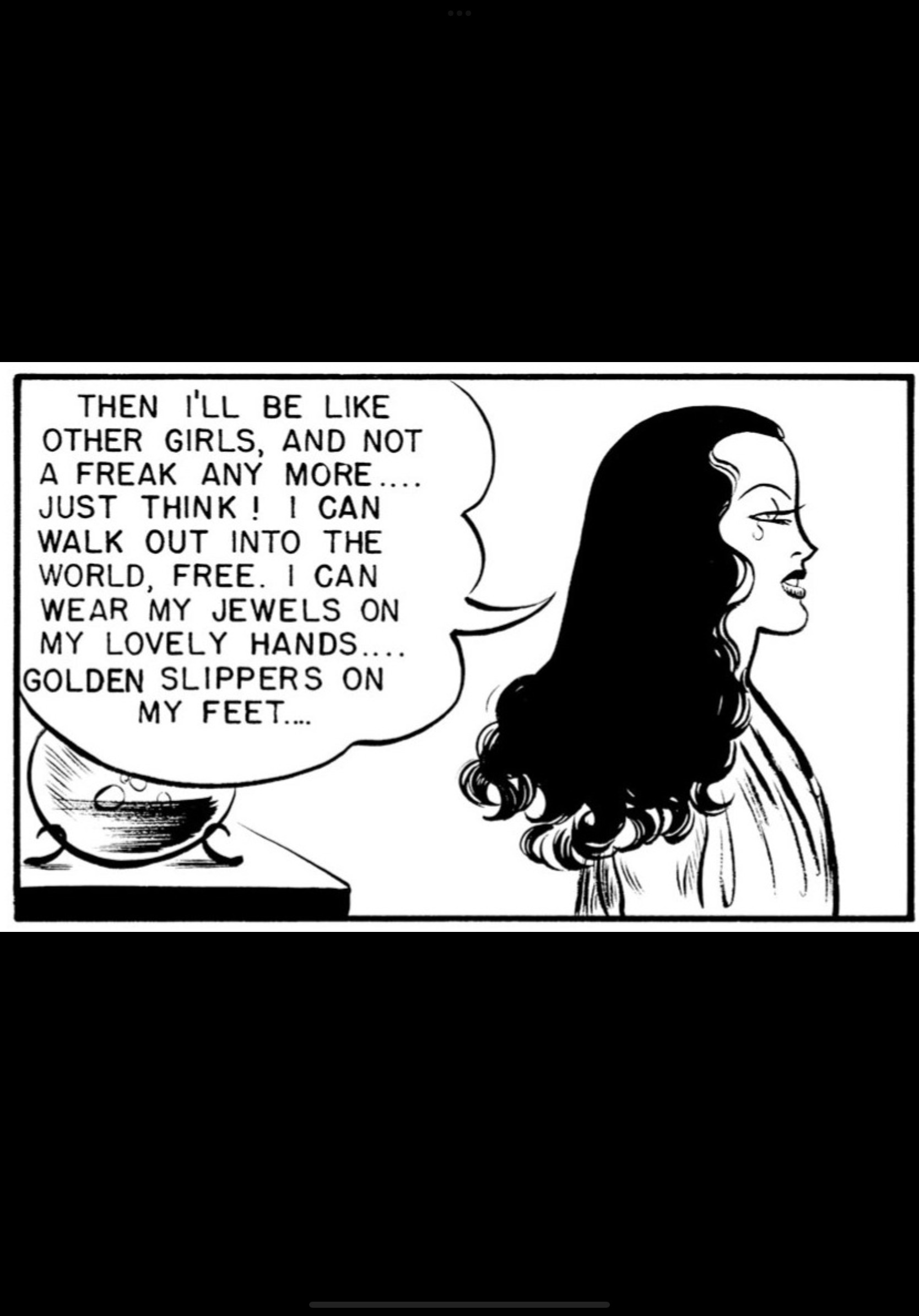

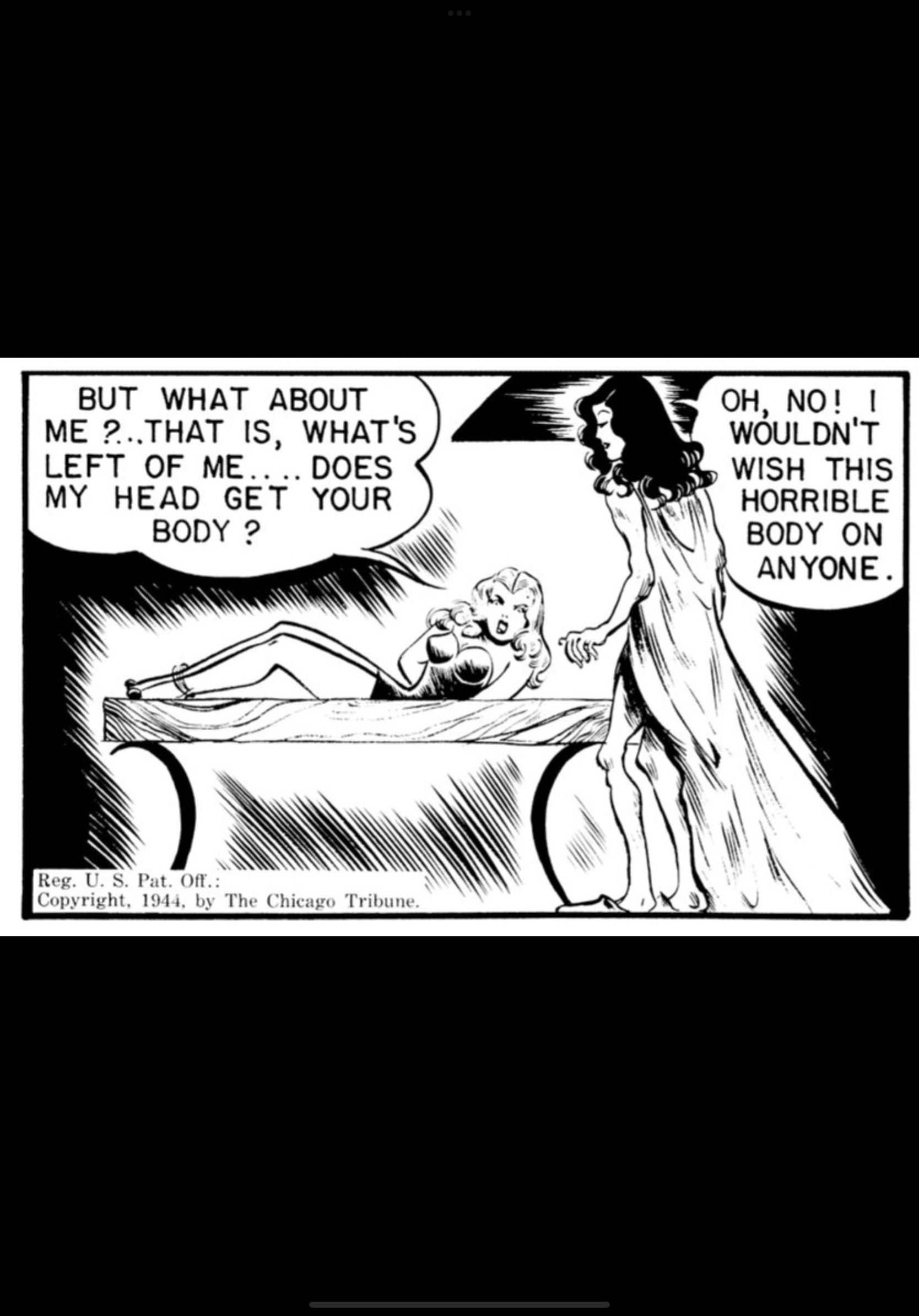

However pioneering Brenda’s careerism may have been, it would be a mistake to see Messick as a prescient feminist radical. Brenda’s heroism was still entrapped in cultural convention. A glamorized, idealized notion of feminine beauty still rules, and romancing the powerful (hopefully wealthy) ubermensch to match this vision is a primary goal for the strip. In fact, the first years of the strip seemed preoccupied with ideas around feminine beauty. In one of Messick’s early and strangest stories, two differently disfigured “Beastly” sisters fall under the sway of a mad doctor who intends to plunder Brenda’s body as parts to replace each sister’s withered pieces. The plot is wonderfully bonkers – a kind of camp that made Brenda Starr forever engaging. Lurking beneath the fun, however, are hints of Messick’s fixation with feminine repulsiveness and beauty. Brenda’s attractiveness is almost superhuman in the hold it has on others, a feminine version of the radical masculinity of pulp heroes. And Messick’s fixation with the beauty ideal, romantic fantasy and glamor often comes out in unforgiving views of everyone else.

While Messick’s fan mail skewed heavily female, she was well aware of her heroine’s crossover appeal. The strip was preoccupied with Brenda’s increasing glamour and attractiveness. but at times, Messick went full cheesecake. In this early 40s Sunday below, Brenda bizarrely narrates an explainer of the recently concluded plot line as we ratchet through a gallery of teases.

Messick’s visual voice and artistic talent were mixed, at best. Her figure and facial work could be painfully amateurish, especially in the dailies. And yet some of the Sundays especially (see above) showed a sophisticated line, silhouetting and perspective that had some of Chester Gould’s poster style and powerful use of blacks. But even into the strip’s later years, her style was wooden and panel progressions pedestrian. Messick would complain that she was never respected or embraced by male cartoonist fraternity. And surely that league included lesser talents than Messick’s.

All of which is to say that Brenda Starr’s cultural importance and inspirational role for women and girl readers especially far outstripped the quality of the strip itself. There was a madcap quality to the strip, its varied and preposterous settings, campy excesses, that kept it entertaining. It does share with the great strips like Gray’s Little Orphan Annie, Capp’s Li’l Abner, Gould’s Dick Tracy however, the feeling of being intimately connected to an author’s personality and sensibility. In the case of Messick and Brenda Starr, I am struck by the strip’s deep sense of ambivalence about the very themes it engages: feminism, ambition, beauty, diversity, fashion. On the one hand, Messick was remarkably inclusive in casting her strip. On the other hand, the strip’s celebration of glamour, narrow ideas of beauty, celebrity, wealth were by definition exclusionary. But perhaps that push and pull, that envy and resentment about the worlds of glamour and privilege that Brenda explores, occasionally occupies, is precisely the point. Messick is working out conflicts that ran deep in late 20th Century American culture.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Fantastic article! A great distillation of comics history as it relates to Dale Messick’s Brenda Starr, with objectivity and a great breadth of perspective.

My memories of Brenda Starr are from the twilight of the strip in 1982-1984 when I and my college friends read it religiously to lampoon it mercilessly. At one point a character named “Boy Brenda” showed up based on Boy George, but in the universe of Messick’s strip the inspiration for Boy Brenda was Brenda Starr herself! The strip became so tepid and lame that the Philadelphia Inquirer accidentally ran the same panel two days in a row and almost no one noticed and only a handful of readers were even bothered enough to complain. The missing panel wasn’t even reprinted in the comics section when it WAS reprinted. It appeared as part of columnist Clark Delon’s opinion/lifestyle piece on the opinion page in which had spent much of the previous year vociferously bashing the, by then, ho-hum legacy comics like Brenda Starr. The missing panel non-kerfuffle essentially proved his point about much of the comics section his own paper ran every day were a waste of ink, time, and resources. Then Calvin and Hobbes and the Far Side arrived almost simultaneously and changed things forever