In the two months since my last roundup of 2023 books, publishers have unleashed a torrent of books aimed at holiday gift giving. So let’s catch up with capsule takes on the more notable releases in this last quarter.

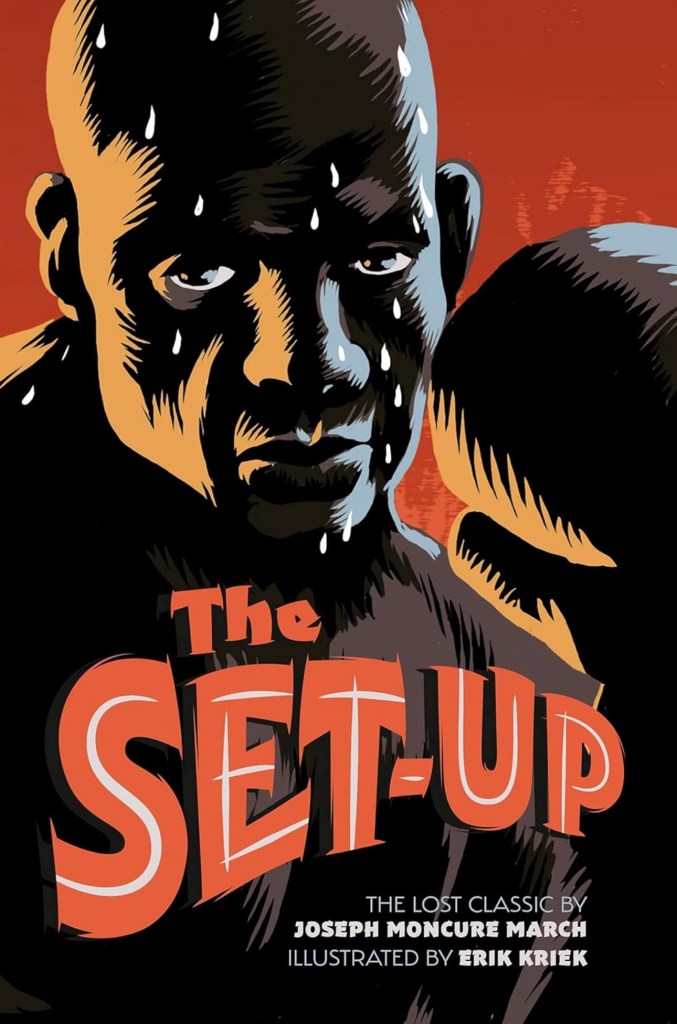

The Set-Up by Joseph Moncure March, with illustrations by Erik Kriek (Korero). Probably my favorite holiday book surprise is this heavily illustrated reprint of Joseph March’s 1928 long poem about the corrupt and pathetic boxing world. Comics oldsters will recall that Art Spielgelman did a similar version of March’s The Wild Party poem over 20 years ago. The Set-Up focuses on aging black boxer Pansy who gets mixed up unwittingly with a gangster/gambler who expects him to take a fall. The poem follows him on the day of the fateful bout, and paints a luscious, dark portrait of the sport and its desperate characters. March uses a hard-boiled, staccato, propulsive language that reminds me of the contemporary crime novelist James Ellroy. Kriek’s art style is not as compelling as March’s poetry, but he chooses his visual punches well and anchors the story firmly in graphic detail. This world March depicts is dark, vicious, racist and raw. It is enormously effective.

Popeye Volume 3: The Sea Hag & Alice the Goon, E.C. Segar (Fantagraphics) This third volume in Fantagraphics’ paperback and portable reprinting of the Popeye Sundays encompasses Segar at storytelling peak – the Plunder Island episode that includes his nemeses Sea Hag and her goon, Alice the Goon. If you dont have this story in one of the many preceding Popeye reprints, then don’t miss this affordable and manageable version. The scale and color reproduction are just right. It is pretty much cut from the larger, more unwieldy and now expensive oversized daily/Sunday reprint issued years ago. No intro material or topper strips this time. But Segar’s remarkable sense of staging, language, absurdity, timing, suspense, are all at their height here.

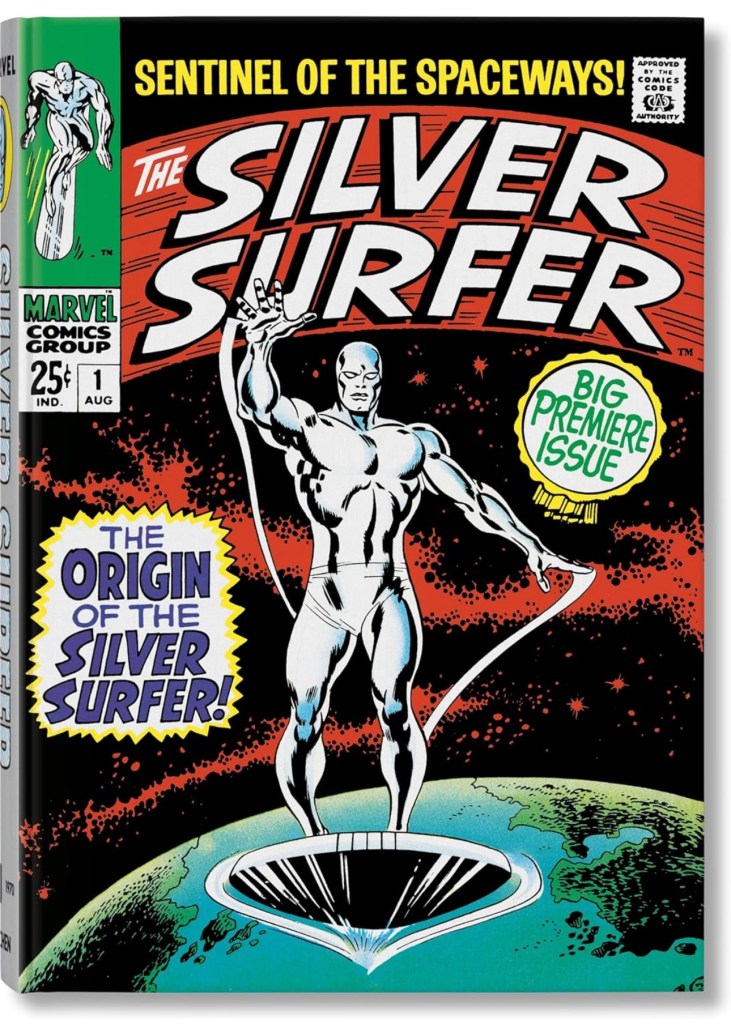

Marvel Comics Library. Silver Surfer. Vol. 1 1968-1969 (Taschen) Taschen books are all about excess, and this XXL sized reprint of the first 18 Silver Surfer issues (700+ pages) at 12.5 x 18.5 inches is all you would expect from such stats. It is a literal immersion in the whacked out world Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and John Buscema crafted in 1968. The stories are reproduced from original comic book pages in order to retain the original reading experience, but at several times the scale. Argue among yourselves whether this is worth $200. But Silver Surfer was Marvel at its peak of melodrama, faux-philosophic seriousness, and visual dynamism. In other words, this was Marvel at its Marvel-est. For myself, I find comic art at this scale brings me closer to the creator’s choices, if not the aesthetic nuance and detail of original art.

Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies 1935-1939: Starring Donald Duck and the Big Bad Wolf (Fantagraphics) . This second volume is especially fascinating because it reflects so many changes within the Disney Studio itself. We get the comic strip riffs of the most successful Disney short of all, The Three Little Pigs. There is an extended test of Donald Duck as a lead strip character that would eventually become a standalone series. During this span, the studio became focused on its landmark feature-length Snow White, which took over the Symphonies strip for a while. And so this reprint volume gives us a unique range of story and style.

The Library of American Comics recently completed the staggering feat of reprinting Chester Gould’s entire run of crafting Dick Tracy, from the early 1930s to the late 1970s. The original first six volumes of The Complete Dick Tracy had been done in a smaller format from the others, so Clover Press and LOAC are reissuing them in a uniform larger format. It is all the same content, but we get nominally smaller dailies packed three to a page rather than two, and considerably larger Sundays. Except for a small selection in Volume 1, the Sundays remain in B&W. This project is really for Gould nuts and Tracy reprint collectors. It nudges us to revisit the strip in the 1930s, which witnessed one of the comics greats develop a visual and narrative style, a concept of villainy and violence that were truly singular in American culture.

Spy Vs Spy Omnibus, Antonio Prohias (DC). Few satires have been as long-lived and consistent as Prohias’ Spy Vs. Spy pantomimes. The Cuban emigre was deeply invested in the deadly Cold War conflict, and his iconic black and white agents reduced it to slapstick tit for tat antics. The plots and mechanisms the two lay for each other suffer relentless backfires, turnarounds and double-crosses. Spy Vs. Spy is satisfying on so many levels. The art is clean and simple. The plotting is so intricate and timed perfectly panel to panel. The punchline satisfying. So consistent. So pure and true to a single vision. This oversized and pricey edition reprints all 241 strips from MAD magazine as well as artist images, sketches, spin-offs and back story. A lot of the material here is simply enlarged and reprinted from the “Casebook” edition published over a decade ago, so that much cheaper version is likely enough for many. This version adds about 60 pages of additional supporting material along with crisp glossier paper and larger reprints.

The Atlas Comics Library No. 1: Adventures Into Terror, Michael J. Vassallo, ed (Fantagraphics). Before commenting on Fantagraphics’ new Atlas comics reprint project I should confess to being an EC chauvinist. My expanding shelves of pre-code comics reprints continue to make the case that Mssrs. Feldstein and Gaines and their stable of artists were miles ahead of everyone else in the field. This first volume in the new Atlas Comics Library offers the first issues of me-too pre-code horror title Adventures in Terror in full. At its best, this net catches fair-not-great work by Gene Colan, Russ Heath, Mike Sekowski, even a minor Basil Wolverton. Fantagraphics charitably likens this segment of the Timely/Atlas/Marvel continuum to B-movie production and mid-tier pulp. This is a kindly frame. The writing is uniformly bad and even the better artists appear rushed and at their least imaginative. Some pre-code publishers had special strength in genres or even effected a consistent, if zany, voice. Some were notably grotesque. But in this case, Atlas publisher Martin Goodman was simply flooding the zone with a lot of copy cat crap that is not improved by aficionado affection or excellent restoration. Select splash pages and perspectives in certain panels can grab your eye, to be sure. Otherwise, this second and third-tier pre-code stuff requires careful curation to retain my interest. The Maneely volume below is more like it. Even better, Fantagraphics’ 2010 Four-Color Fear remains the best compilation of genuinely fine non-EC horror I have seen.

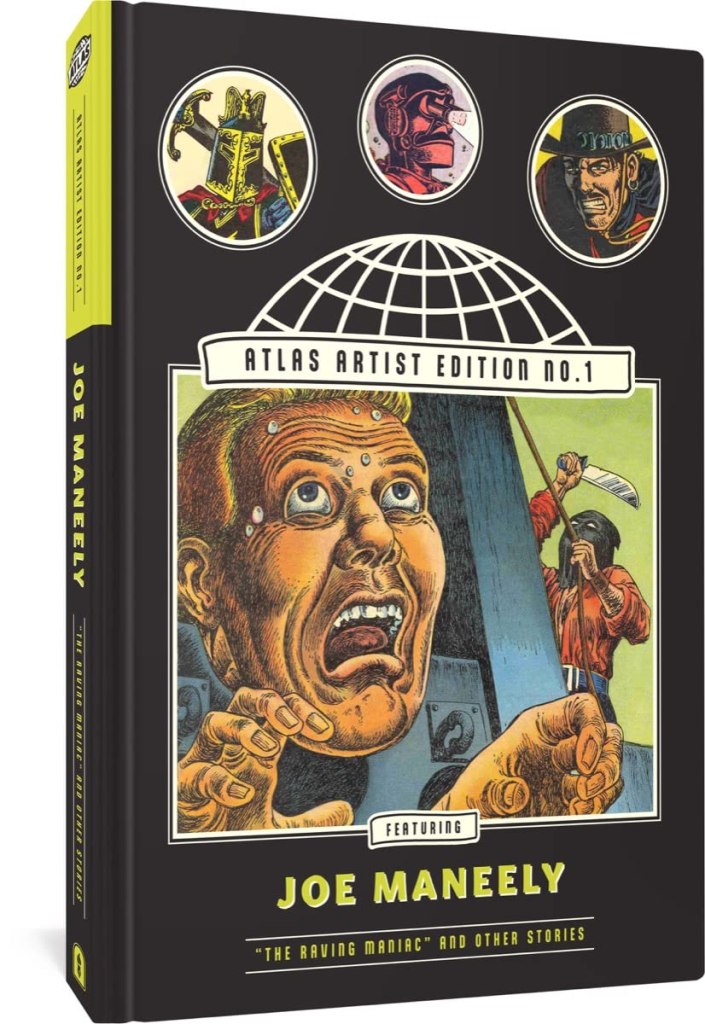

The Atlas Artist Edition No. 1: Joe Maneely, Michael J. Vassallo, ed (Fantagraphics). While I may find the full issue Atlas reprint project of limited interest (see above), this oversized zoom into the Atlas work of Joe Maneely is a better use of the early Marvel archive. Before his premature, tragic death in at age 32 in 1958, Maneely was the shooting star of Atlas’s freelance stable. Editor Michael Vassallo calls him the publisher’s Jack Kirby of the 1950s. Maneely worked across western, horror, satire, sci-fi, war genres and more, often inaugurating new titles and setting tone and style for the series. More than 250 pages of nicely restored comics stories in a 10.1 x 13.8 inch format sample across his short career. Maneely was a cut above the non-EC artists, although I find him more deft and competent than masterful. The joy of this book is watching an artist’s fast maturation from a stiff and prosaic style into real expressiveness in rendering both faces and figures, a creepy use of shading and skin textures, more thoughtful page layouts and panel progressions.

The Bitter End and Other Stories, Reed Crandall (Fantagraphics). Now this is more like it. Fantagraphics continues its EC Comics Library reprint series with this focus on Reed Crandall’s work for the suspense and horror titles. Even when Crandall’s figure and face draughtsmanship was still developing, he brought to every panel a mature feel for background, setting, point of view and staging. Every panel serves a dramatic purpose and seems thought through. Crandall’s is the kind of talent that EC attracted and sought, and it is what gave the publisher a level of quality that rivals hit only sporadically. Like all of the volumes in this series The Bitter End highlights the art with sharp black and white rendering. This works especially well for Crandall. He had a strong sense of setting, investing his backgrounds and environments with obsessive detail, intricate line work, layers of shadow that can disappear into garish coloring. This title devotes a final section to reprinting ten stories drawn by the less talented George Roussos. While not a compelling visual storyteller, Roussas did have a distinctive use of shadowing and light sourcing…and a lot of ink. This series excels at helping us watch artists evolve across time and genres. They put a different lens on the oft-reprinted EC titles.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.