This is a perfect time for a Mucha revival, I think. Advertising creative is exploring new depths of cultural irrelevance. Marketing seems to have become an unimaginative haven for data scientists and bureaucratic functionaries. And company efforts to align themselves with social progress and “meaningful branding” are now in full, cowardly retreat. And so, reviving both the art and thought of perhaps the greatest advertising illustrator of all time, Alphonse Mucha is not only welcome but necessary.

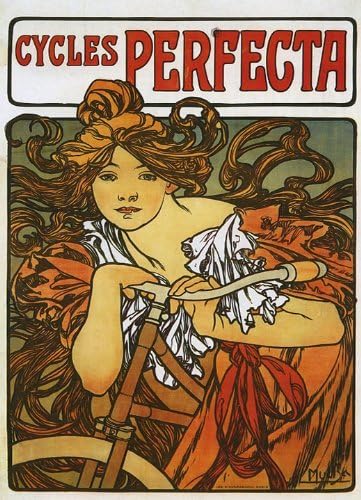

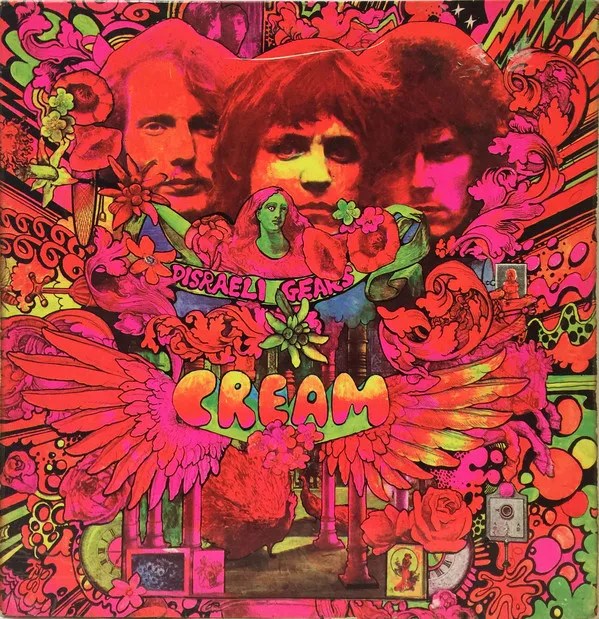

You probably recognize Mucha even if you don’t know him. Perhaps the leading figure in the Art Nouveau movement at the turn of the 20th Century, his languid, erotic femmes, their organic, flowing tresses, the cartoon planes of color and dense outlines, the symmetry – are immediately recognizable. His ads for Job cigarette paper live on, as do his Cycles Perfecta and Biscuits Champagna promotional posters. His influence on the cartoon arts are evident in Winsor McCay most obviously, but then 60 years later on psychedelic poster and album artists like Wes Wilson and Stanley Mouse.

But perhaps more to the point about the timeliness of a Mucha revival, this illustrator truly believed he was doing God’s work. His use of color, symbol, organicism and symmetry were genuine attempts to invest spiritual resonance in things – yes, even in consumer commodities. At the turn of the new century of industrialization, cold scientific mechanization and the market logic of consumer capitalism, he crafted a vision of satisfying, not stultifying abundance. His religious and mystical bent saw a spirituality coursing through all of nature, man-made objects, humanity and the cosmos. His ads for bicycles and biscuits may loom fresh and energizing more than a century later simply because of the relevance of his ambition. He believed in the depth of surfaces. He surrounded those mass commodities not with claims of “artisanal care” or “sustainability” values but with fecundity – flowers and vines, beautiful symmetries, spiritual allusions. You were not buying a commodity. You were buying into a vision of a spiritually charged cosmos of which that biscuit was a natural part. To appreciate Mucha is to understand just how parochial and culturally irrelevant advertising has become.

Mucha’s was a vision of things and spirit that cannot be expressed in words but best experienced through imagery. And that was his point. The magnificent oversized version of The Century Guild Museum of Art’s Le Pater: Alphonse Mucha’s Symbolist Masterpiece and the Language of Mysticism by Thomas Negovan gets us closer to appreciating Mucha’s genius, and why we could use some of it now.

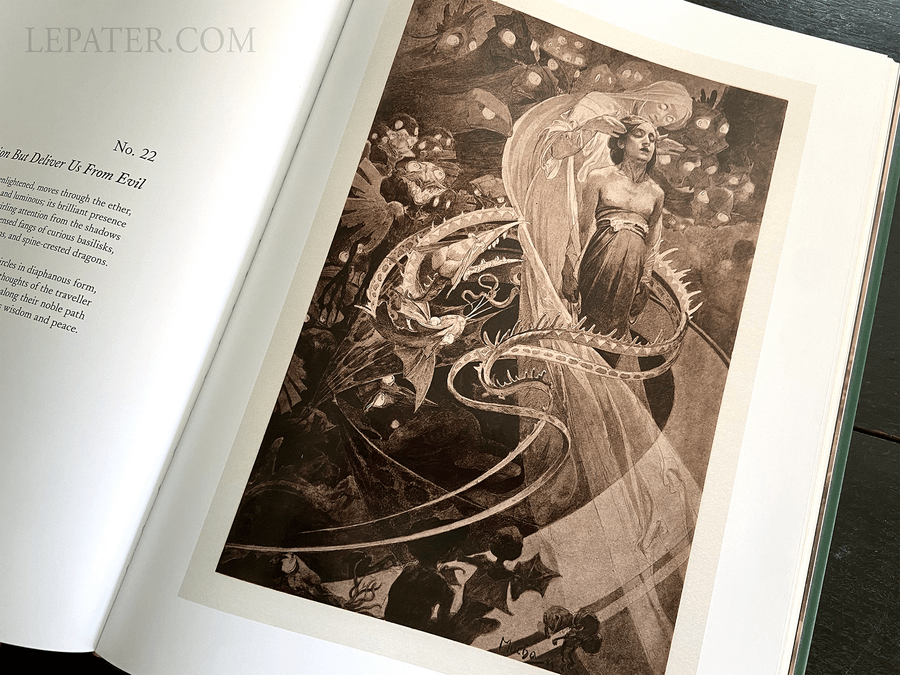

This deliciously printed volume reproduces and explains Mucha’s 1899 book Le Pater, an illumination of the Lord’s Prayer. In a series of symbol-rich visualizations of each line of the prayer, Mucha invokes classic religious imagery, the geometric symmetry of Masonic traditions, emblems of fertility and nature – all to give a richer sense to the most familiar of Biblical passages. The book was printed in a limited run of 510 copies, but the original art was widely praised in a series of showings, including one in Chicago in the first years of the century. Mucha himself traveled to the US and set up shop in New York City during the early 1900s.

Some of this work is truly breathtaking in demonstrating the depth of surfaces, the ability for image to transcend language and evoke deep feelings. His rendering of “Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil,” is especially powerful. Mucha envisions temptation as an atmosphere of menacing serpents encircling a youthful soul who is being guided through their treachery by a luminous angel covering her eyes against the evil. The visual contrast between evil and Godly symbols, the diaphanous, radiating innocence finding peace at the center of a jagged, ravenous fallen world of evil, is gut-wrenching. The countervailing senses of peril and salvation are palpable in Mucha’s mastery of light and dark, sharp detail and the ethereal, composition and of course symbolism.

So why is Mucha important now? Well, history matters, insofar as we make the past “usable” in the present. In some sense, this is why the counter-culture artists of the 1960s found inspiration in Mucha who was also trying to express and understand an era of discomfiting change. At the end of the 1800s, he leaned forward into the century of commodity capitalism and mechanization by going backward into religious symbolism (divine meaning in things) and organic forms. His use of symmetry came from ancient arts of geometry not the machine, even though it alluded to a new mechanical age. These images would make sense to the counter-culture and New Left politics of 60s youth. They, too, were looking to go forward by invoking pre-modern tropes – participatory democracy, back-to-the-land agrarianism, spirituality. Their psychedelic evolution of Art Nouveau was, like the original, a rejection of realism and technocracy.

But unlike our own age, the psychedelic poster makers and underground cartoonists of the 60s worked in a pop culture environment that was already in the process of reawakening. Film and TV were in a dark age, but design, literature, music and fine art were taking leadership roles in the culture. Think Milton Glaser and George Lois, Pynchon, Heller and Dr. Seuss, Andy Warhol, Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan, etc.

Clearly things are bleaker now, in that no green shoots are apparent in any area of culture that seem to be pointing the way forward. Worse, the post-mass media ecology is one of niche content and minor audience clusters where no visionary even has a platform for breaking through with a grand unifying vision. Advertising and marketing, the fields in which Mucha excelled, are so busy following the data and “the consumer” (which they often mistake for culture) their fields have attracted a generation of bureaucratic functionaries and trend chasers. Just look at the last five years of Super Bowl ads and this year’s Cannes Lions winners. It is all boilerplate now.

So what can Mucha do for us now? Not sure, really. I do know that we are at a cultural impasse where his kind of utopian vision, his synthesis of past and present into an imagined path forward seems impossible but necessary. And it is interesting that both the eras of Art Nouveau and 60s psychedelia artistic expression sought organic and mystical symbolism to set against the threat of technological, industrial dehumanization. Sounds familiar.

But I do suspect that history, or at least history-making, is about to be important again. Cultural murmurings are apparent. Much of literary fiction is preoccupied with the past as setting now. Colson Whitehead, George Saunders, Louise Erdrich come to mind. An emphasis on folk and domestic arts, texture, in the fine arts is at least a recollection of a pre-screen relationship to art. Even the weird and campy past of Bridgerton has that feel of looking for utopian paths in a reimagined past. Far and away the most promising and rewarding attempt at collapsing history in service of a coherent future is Afrofuturism – especially in lit (Octavia Butler) and music. These all strike me as early gestures towards a usuable past.

The great American literary and cultural thinker Van Wyck Brooks coined the term “usable past” a century ago to reframe history as more than getting facts about the past straight. He meant that in history we find inspiration for the present. Surely, we are always looking for cautionary tales. Consider all of the historical hand-wringing right now over the rise of European fascism in the 1930s. But we also look for how in the past we solved for cultural tensions and imagined a mew synthesis. Mucha’s mystical vision of a spiritually satisfying consumer culture may seem risible in retrospect…for all of the spiritual damage consumerism did to us and environmental harm it has done to the planet. But his Art Nouveau vision did help marry style to substance, make popular images, industrial design and even advertising truly meaningful. These leadership, creative, utopian qualities are so absent in our arts and commercial culture today that looking backwards at a giant like Mucha is at least a start in reimagining what such cultural creativity entails.

The Century Guild’s production is up to the job of faithfully reproducing the nuances of Mucha’s work. It is available in a deluxe 12×16-inch hardcover with peerless scans of Le Pater and a well-illustrated and light treatment of Mucha’s career and thought by authority Thomas Negovan. Curious minds will want to dig elsewhere for a deeper treatment of Mucha’s life, thought and art. But this is a good start. It is also available in a more affordable, updated softcover edition with 16 pages of additional material.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Shelf Scan 2024: Necessary Reprints – From Anita Loos to Betty Brown – Panels & Prose