Frank King’s Gasoline Alley may be the “Great American Novel” of the 20th Century we didn’t know we had. This remarkable multi-generational saga of the Wallets evolved in several panels a day across decades, exploring the domestic and emotional lives of small town Americans during a century of intense change. And in its heyday during the post-WWI era, this strip was singular in its affectionate embrace of suburban family life at a time when post-war disenchantment overwhelmed the intellectual class, when glamour, sex and emotion dominated the film arts and magazines and glitz dominated Hollywood. When more famous social commentators like H.L. Mencken, Walter Lippman and Sinclair Lewis lampooned, decried and doubted the small town American intellect – the so-called “revolt from the village” – King celebrated what Mencken called the “booboisie.” Comics historians often characterize the post-1915 period of the medium as a kind of literal and figurative domestication. As newspaper syndication expanded into every burg, the mass media business of comics needed to shave the edges off of a once-raucous and urban-focused art form. Shifting the focus to family relations and suburbia, relying on more repartee than prankish violence, made the comic strip more acceptable to a mass audience.

Which is fine so far as structural explanations of modern popular culture go. Understanding that the content of any mass medium is constrained by the economic, ideological and cultural interests of its owners still begs the question of what individual artists did within those limits. And in the case of Frank King, who was at once a sentimentalist and an artistic innovator, the domesticated comic strip was a platform for exploring the emotional nuances of the common Americans that were being devalued elsewhere in the culture.

We have covered in previous posts the arrival of the orphan Skeezix into bachelor Walt Wallet’s life in 1921, the genius of Gasoline Alley’s gentle world, and his talent for dramatizing the tiniest moments of human connection. But the run-up to Walt’s engagement and marriage to divorcee Phyllis Blossom in 1926 is penultimate King. Here he marries his attention to emotional detail to his equally subtle penchant for visual innovation.

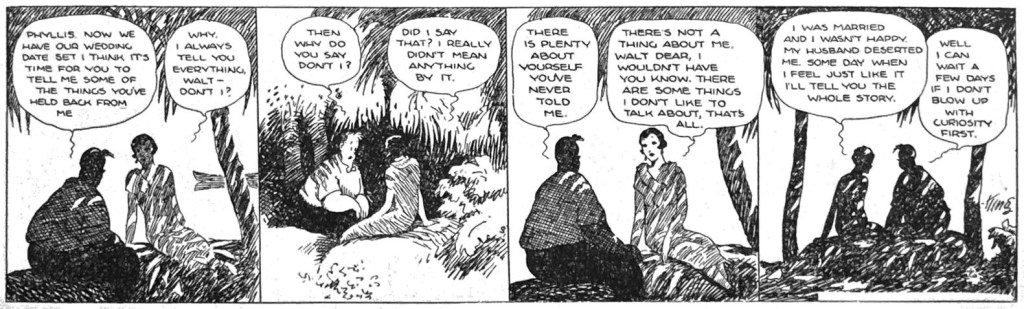

For many months, Walt agonizes over his feelings for “Mrs. Blossom,” her dalliances with other men, Walt’s jealousy, the eventual proposal, revelations about Phyllis’s previous marriage and then the wedding itself. is one of the slowest burns in 20th Century storytelling. The four-panel-a-day cadence of the newspaper comic strip is the only medium where such a tease would be possible…or tolerated. Until, that is, the arrival of the radio soap opea in 1930, which in many ways this Gasoline Alley episode foreshadowed. But King uses this slow, slow burn to explore complex and conflicted inner lives in both story and visual experimentation. He masterfully deploys a range of visual tactics to immerse us in the emotional nuances and contradictions of a budding romance.

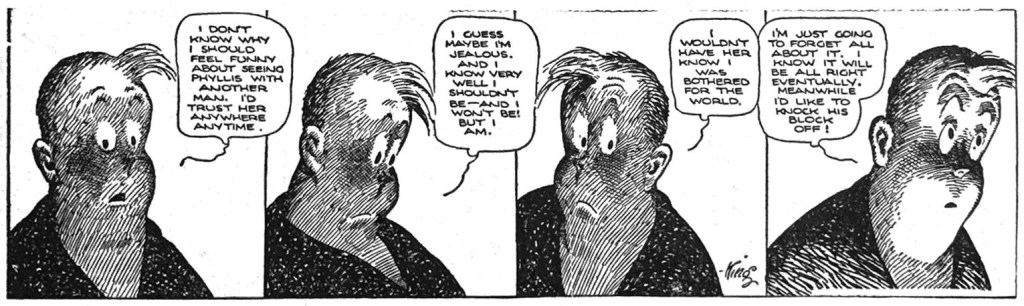

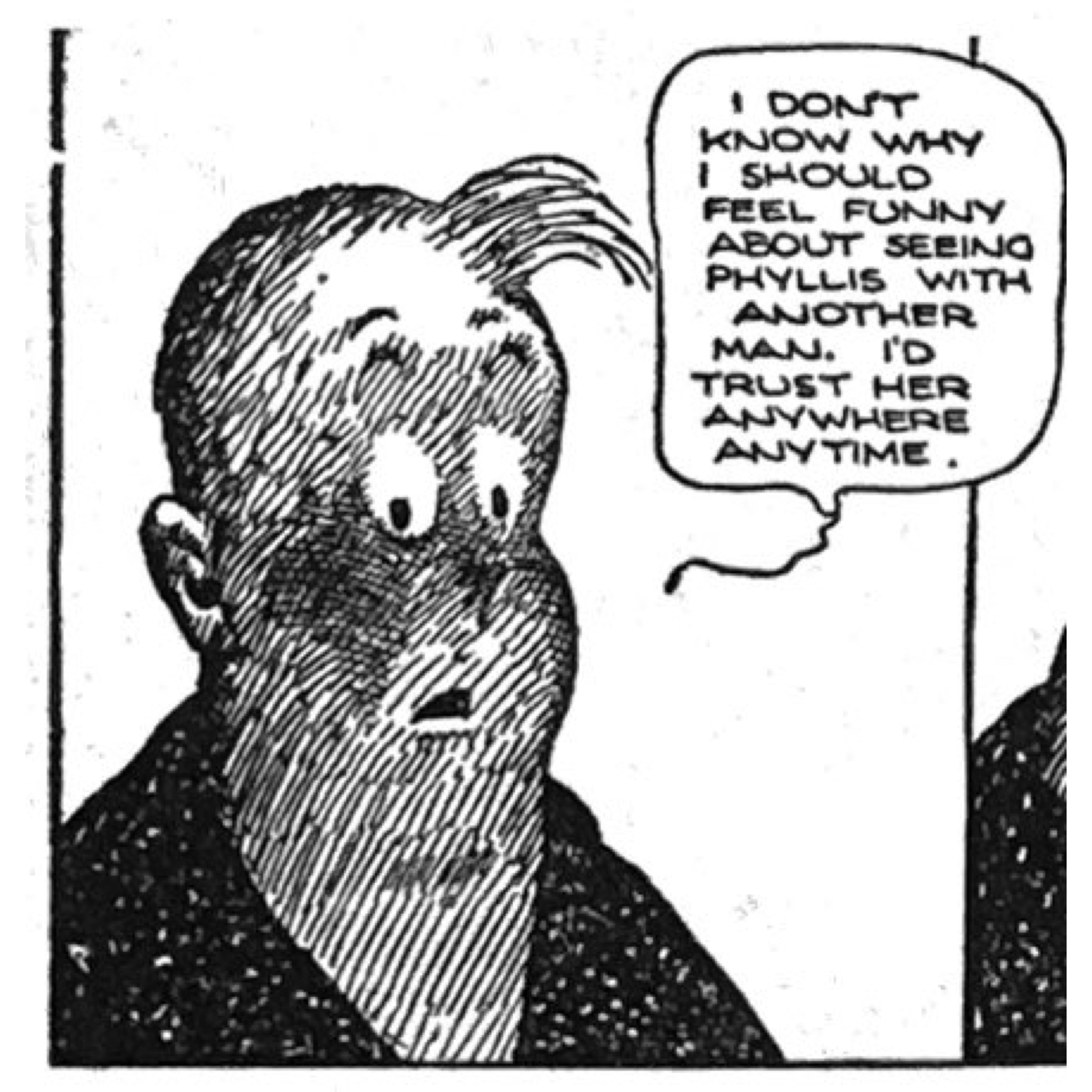

Take, for example, this remarkable strip of shadowy close-ups designed to express conflicted emotions. In sharp contrast to his usual open-air, plain-line style, King radically changes modes to go inward. The interior monologue was foundational to the modern comic strip, but here King uncharacteristically brings us in close, uses hatch lines to suggest Walt’s sadness, slight shifts in head positions to dramatize him arguing with himself. That final panel, which reverses the light source suggests a dramatic conclusion, but his words maintain the conflict. After all of that inner chatter, nothing really has changed. King is playing with framing, mood, light sources that may draw from contemporary silent film or painting, which he was always apt to do. Regardless, he marshalls these techniques to dramatize a complex, very modern, state. Walt is self-conscious of his irrational emotions and yet unable to contain them. To be self-aware of one’s lack of self-control is arguably the realization that we are psychological beings, one of the hallmarks of the “modern” world.

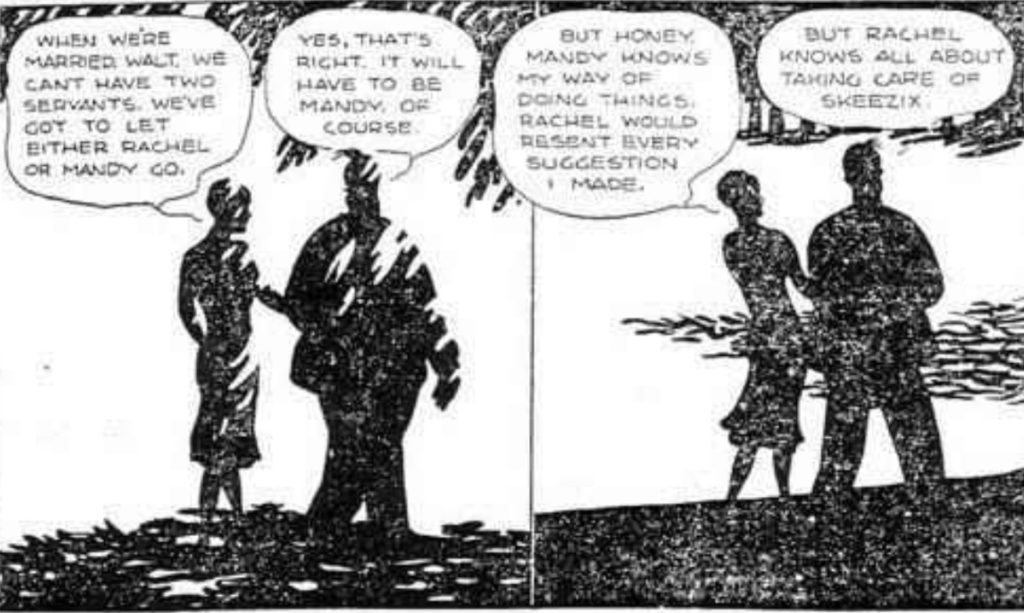

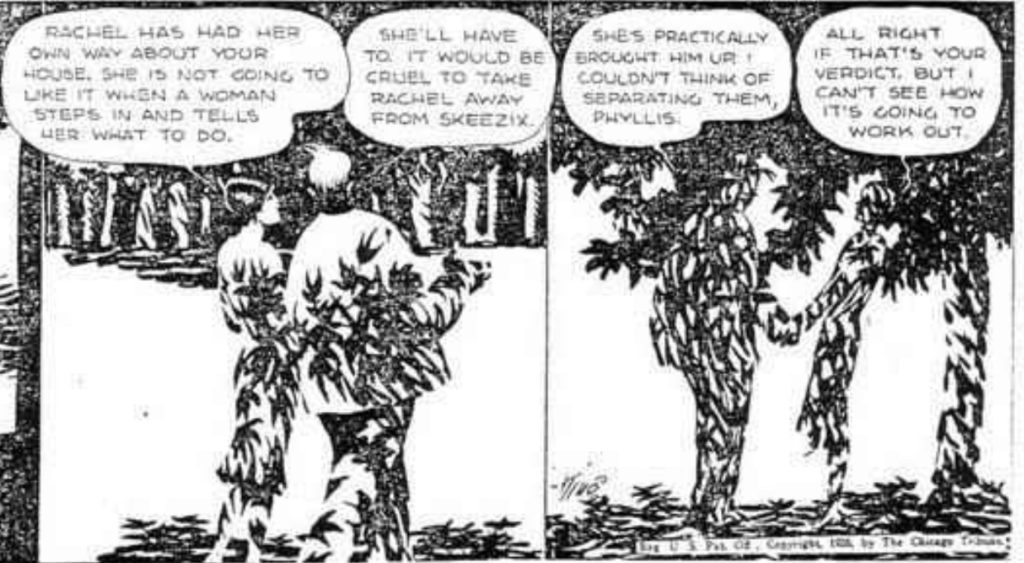

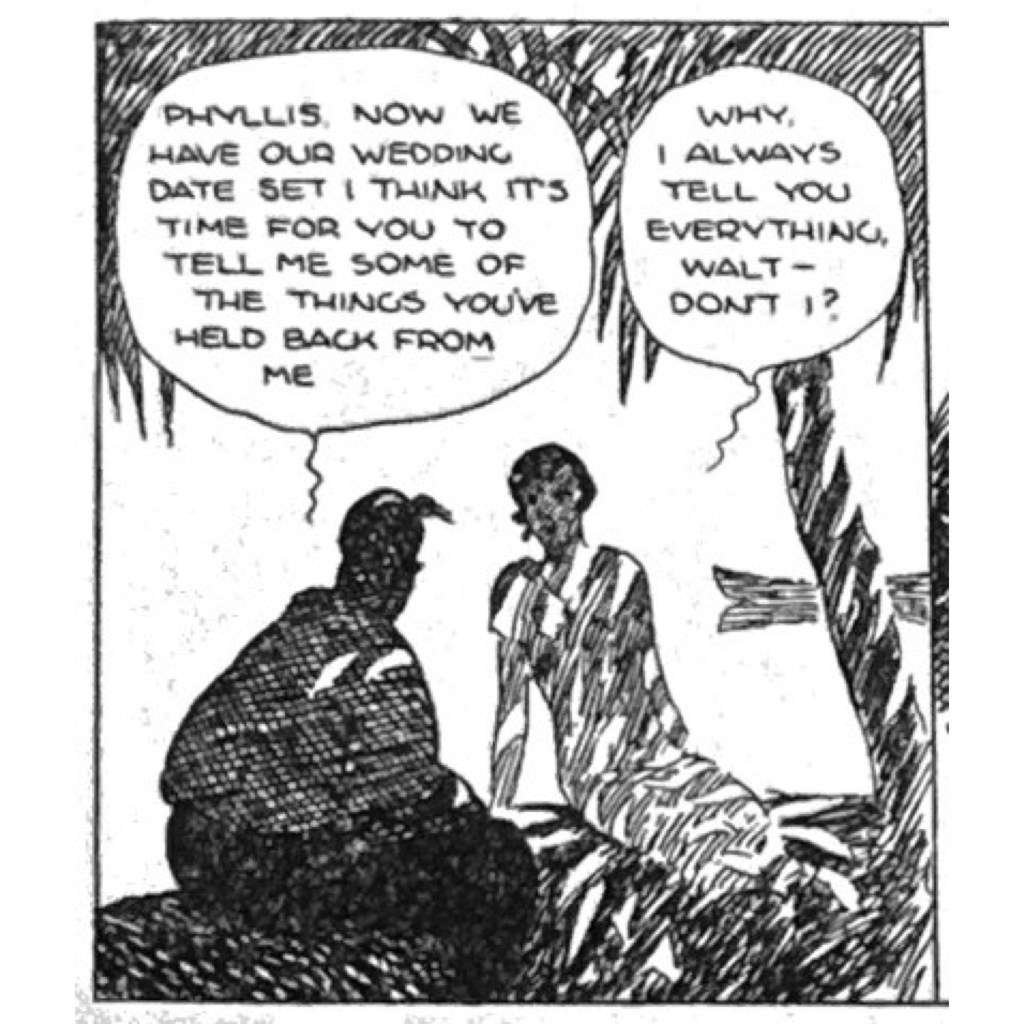

Clearly King was going through a period of visual play during these final months of Walt and Phyllis’s courtship, engagement and marriage. He seems especially interested in lighting effects both for conveying emotion as well a intimacy. The couple discuss matters large and small – from which housekeeper to the revelations around the divorcee’s previous marriage. But King repeatedly puts the couple into silhouette and under sun-drenched trees, casting a mottled sunlght onto the conversation. The effect intensifies from panel to panel, until Walt and Phyllis become an odd collection of blotches.

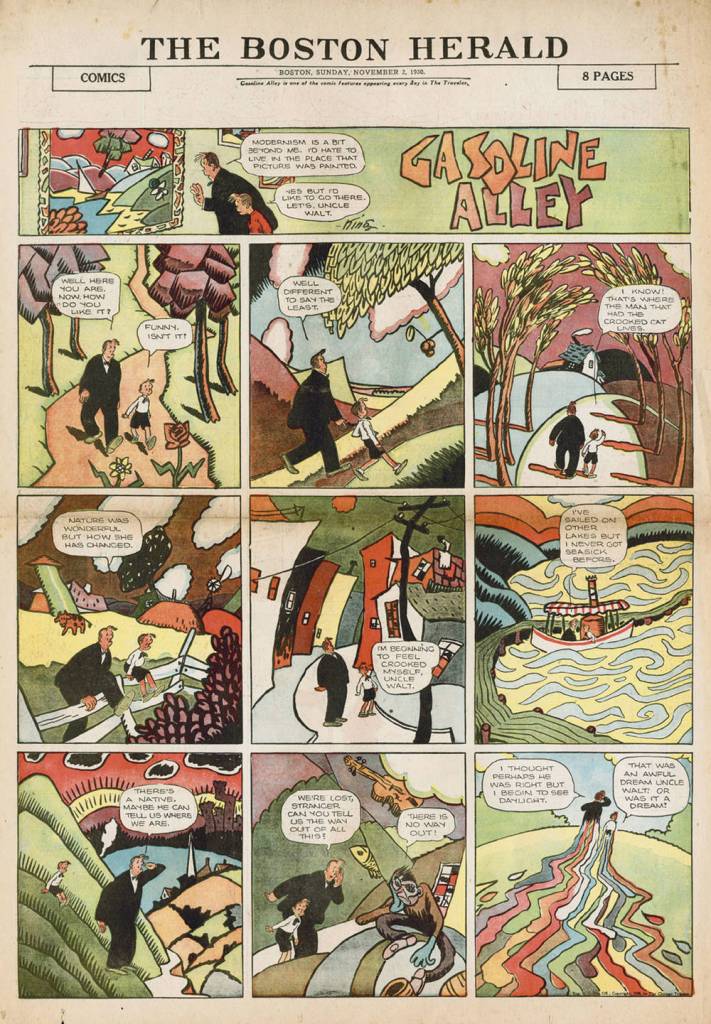

We could simply regard this period of Gasoline Alley as a talented cartoonist at play, using his strip to test out styles. As many cartoon historians are quick to note, Frank King was well aware of contemporary high art styles. He was among the newspaper illustrators who mocked the eccentricities of European Cubism that American audiences first encountered at the 1913 Armory Show, for instance. Jeet Heer argues that this introduction to the avant-garde influenced King’s comic styles and helped make him a “master of domestic Modernism.” This attempt to align early 20th Century comics with Modernist styles of art and literature has been gathered recently in Jonathan Najarian’s anthology, Comics as Modernism: History, Form and Culture. Najarian opens this book with King’s own famous Nov. 2, 1930 Sunday Gasoline Alley, in which Walt brings Skeezix to a Modernist art exhibit and the two walk through a warped landscape of Cubist and Fauvist abstractions. Heer, Najarian and others argue, with some justification, that avant-garde art was in some ways catching up to the comics, which for years already had been expressing visually the same modern sensations of speed, compressed time, fragmented perspectives, etc. At the beginning of that oft-cited Sunday strip, Walt expresses characteristic American doubts about the value of extreme abstraction. “Modernism is a bit beyond me,” he says before they dive into the disorienting dreamscape. In this same anthology, art historian Katherine Roeder only half believes Walt’s protest, since, after all, he proceeds to immerse us in a pge of faithful renditions of post-Impressionist art styles. “There is evidence of a push-pull operational aesthetic taking place within comics, an aesthetic that verbally articulates the reader’s apprehension about modern art while visually acclimating them to its formal language os abstraction (Najarian, p. 46).”

I am not so sure. I am inclined to take King and other cartoonists at their word, that Modernism was a bit beyond them. I would be the first to agree that early 20th Century American cartoonists and avant-garde painters were struggling to solve for similar problems around depicting the modern experience. Traditional sensations of time, scale, space, community, even a sense of self, were challenged by new physical environments and technology. Personally, I believe the explosive popularity of comics at the turn of the 20th Century came from the medium’s unique engagement with the inchoate sensations of the new world. But while I think cartoonists and Modern artists borrowed from one another at points, I also think that the fetish around aligning comics as a kind of Modernist art is misguided and misses a more fruitful line of inquiry.

Some of the most dogged critics of European post-Impressionism were the very American painters who overlapped with the cartooning world. I will tell this story at greater length in an upcoming post, but it is important to note this concrete connection between comics and painting at the time. The Ashcan and American realists of 1900-1915, namely John Sloan, George Luks, George Bellows, William Glackens, Everett Shinn, and especially their teacher and ringleader Robert Henri, often resented the European invasion and generally tried to establish a native American art that was grounded instead in representational (realistic) aesthetics. Not coincidentally, many of these artists themselves started as newspaper news illustrators and occasional cartoonists. Many of them even displayed at that infamous Armory Show that introduced America to the avant-garde. But they felt betrayed by the organizers when representational American canvases were literally pushed to the edges of the exhibit hall to give the European revolutionaries center stage. Worse, the Americans were excluded altogether from the traveling Armory Show that visited major American cities. My point is that reticence about Modernist artistic solutions was not a sign of simple philistinism. At least until 1950, there was a persistent American realist school of art that resisted the conceit that European high Modernism represented “progress” in art. Artists like Sloane, Glackens, Shinn and eventually Edward Hopper, Reginald Marsh and the great triad of 30s Regionalists, Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry, offered an alternative path that absorbed some of European Modernist stylings but in a representational approach to depicting an everyday “American Scene.”

Rather than wave about vague associations of comic aesthetics to high Modernism, I think an adventurous cartoonist like Frank King demonstrates how cartooning was much more closely aligned to 20th Century American Realist art. In exploring Walt and Phyllis’s complex romance, King incorporates some of the techniques of expressionist lighting and mottled, almost cubist fragmentation. But it is in the service of depiction. He is exploring ways the medium can express complex emotional states.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Of all the bloggers I subscribe to, you have the most depth of knowledge and insight to both the artist and the zeitgeist of the period. How could I convince you to review my books?

Albert

Edmund Dulac- His American Weekly Collection

Of all the bloggers I subscribe to, you have the most depth of knowledge and insight into the artist and the zeitgeist of the period. How could I convince you to review my books? Not comics per se, but published in newspapers and definitely art.

Albert

Edmund Dulac- His American Weekly Collection