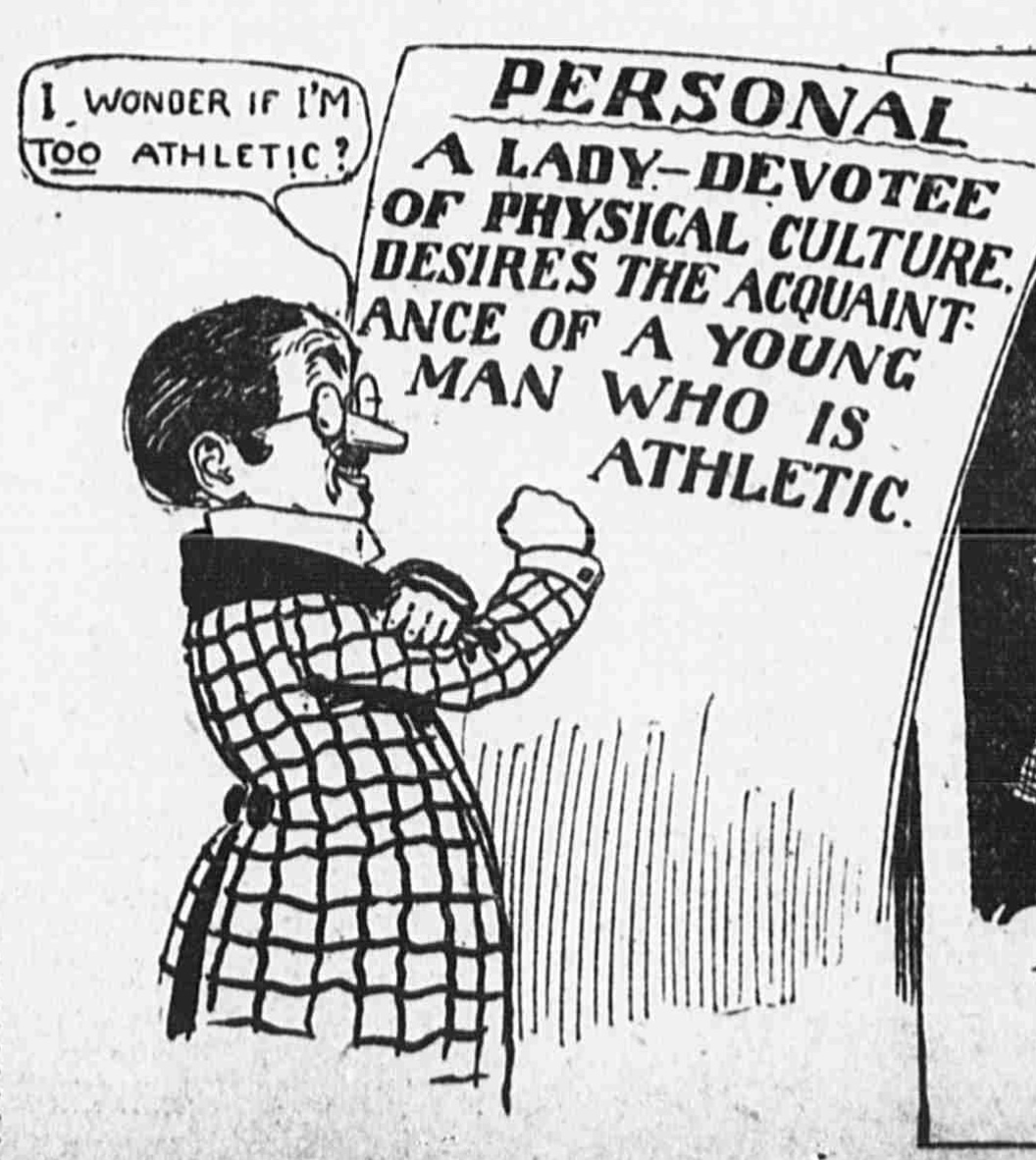

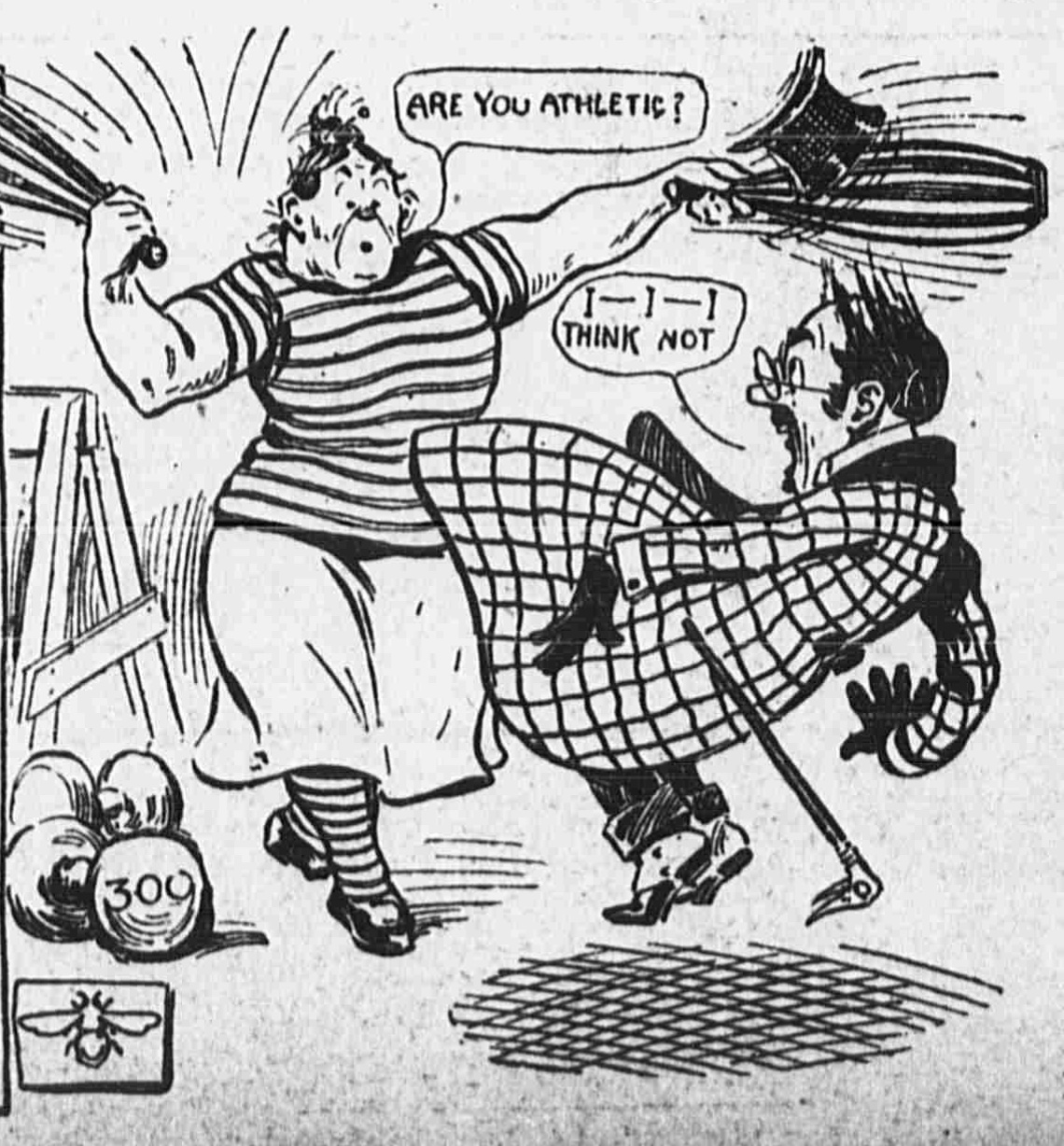

Apparently, getting a date was never easy, and the contemporary swipe-left, swipe-right mobile media is just the latest twist on an old genre – the “personals.” This short-run comics series of 1904, “Romance of the ‘Personal” Column,” in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World reminds us that Americans were already jaded about the deceptiveness of these early versions of the dating app over a century ago. The strip followed a familiar formula. Our misbegotten suitor finds that the reality of his blind date is frighteningly different from his impression of the ad. Thus, he flees in panic; from a widow’s horde of kids, a muscle-bound athlete, and, in a racist turn that was standard in the day, a “dark brunette” who turns out to be Black. “Romance of the ‘Personal” Column” only ran a handful of times, but it is the kind of early comic strip trifle that surfaces a number of important themes in the cultural history of the first newspaper strips.

Allan Holz’s American Newspaper Comics dates this strip running as a daily from Feb. 11 – March 8, 1904 in The New York World. The strip is unattributed by name but signed with a cartoon bee. I could only find a week of strips myself, so I can’t tell if “Bee” developed this idea in any more interesting ways. But even in this scant sample a few cultural features of the early dailies come through. Unlike the more colorful Sunday comics sections, cartoons in the dailies enjoyed greater latitude to address adult and male themes. The Monday-Saturday numbers focused more on political, business and sports news without the broader lifestyle, trend, kid content aimed at the whole family. In fact, the figure of the young middle class striver was a common type in the first decade of the newspaper comics. This was after all the age of an emerging managerial middle class, young men navigating a new world of cityscapes, evolving gender relations and new opportunities in corporate America. Finding a mate in a city of strangers was just one of the challenges.

In fact, “Romances” shared space in the World’s back pages with yet another send-up of the same urban sharpie – Mr. Peewee. Generally acknowledged as the first truly daily modern newspaper strip (Sept. 1903 – Sept. 1904), that series lampooned the up-and-coming braggart as a tiny dude with oversized ego and boasting designed to impress the ladies. H.A. MacGill. one of Mr. Peewee’s several artists, would further develop this character of the modern American man-on-the-make in the long running “Percy and Ferdy” series, which began life as “The Hall-Room Boys”in 1906. Here, two low-level, poorly paid clerks cosplay affluence and cultivation in order to win over women. Part of the great fun and cultural fubnction of the newspaper comics in their first decade was just kind of cartoon sociology. They were helping to map out the new social reality of this strange city environment by ordering the chaos around a cast of ethnic, social, class types. This was not new. Much of 19th Century American humor revolved around dialect, regional stereotypes and the national pass time of bullshitting. It poked at regional, ethnic and class differences through caricature and overgeneralization. But this kind of regional humor also assuaged anxieties around the coherence and identity of the American experiment as it expanded into strange new worlds to the West. Turn-of-the-century strips like Romances, Mr. Peewee and Percy and Ferdy satirized modern social types as they were also organizing the city experience around them.

Nor were perosnal ads new. According to some media historians, the form started in periodicals during the 17th Century, when rich men were known to announce their openness to marriage. By the latter half of the 19th Century, personals had become a major source of income for many newspapers. Some high profile scams were reported around phony perosnals ads and many newspapers had ended the practice by the time of this cartoon series.

This strip, like Mr. Peewee, is notable in its media self-consciousness. Both strips are mocking the sensationalist style of Pulitzer and the World’s main rival in the New York market, William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal American. Dubbed in all of these satires as “The Daily Fudge,” the Journal was infamous for its visually and conceptually inflated headlines as well as a robust personals section that occasionally reached onto the front page. Media reflexivity, self-references, “meta” narratives, breaking the fourth wall, et. al. are not inventions of our so-called post-modern moment. At the dawn of mass media, the media talked incessantly about itself, called attention to its own artifice. Newspapers and magazines were openly critical of one another and their rhetorical devices. Indeed, one of the earliest uses of the term “Fake News” was aimed at Joseph Pulitzer’s controversial but highly lucrative reporting.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.