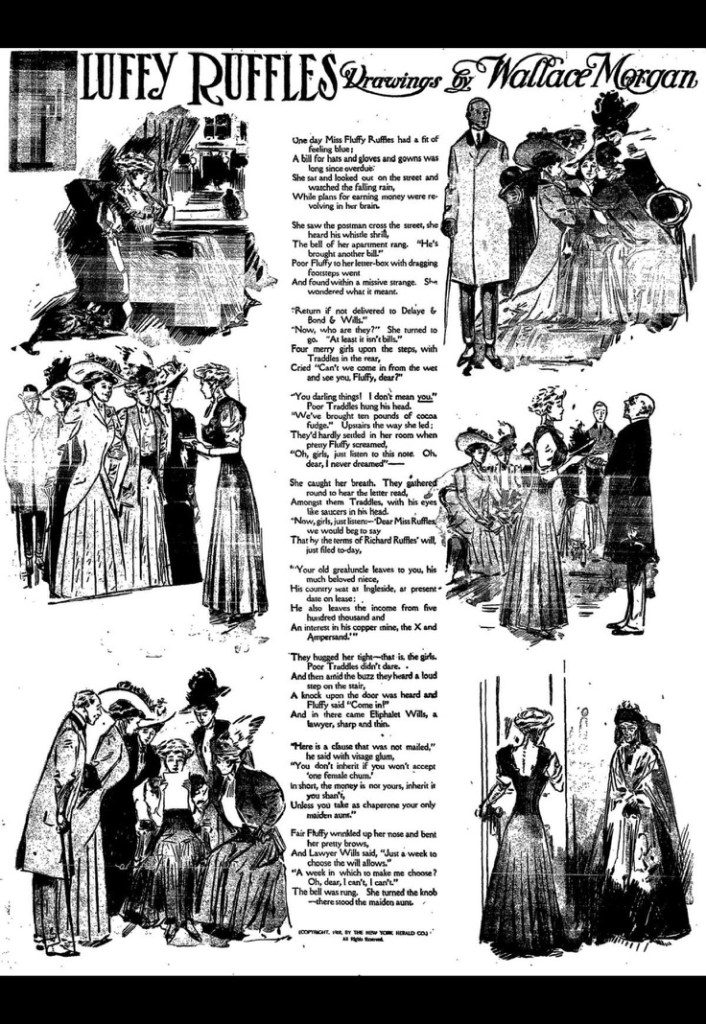

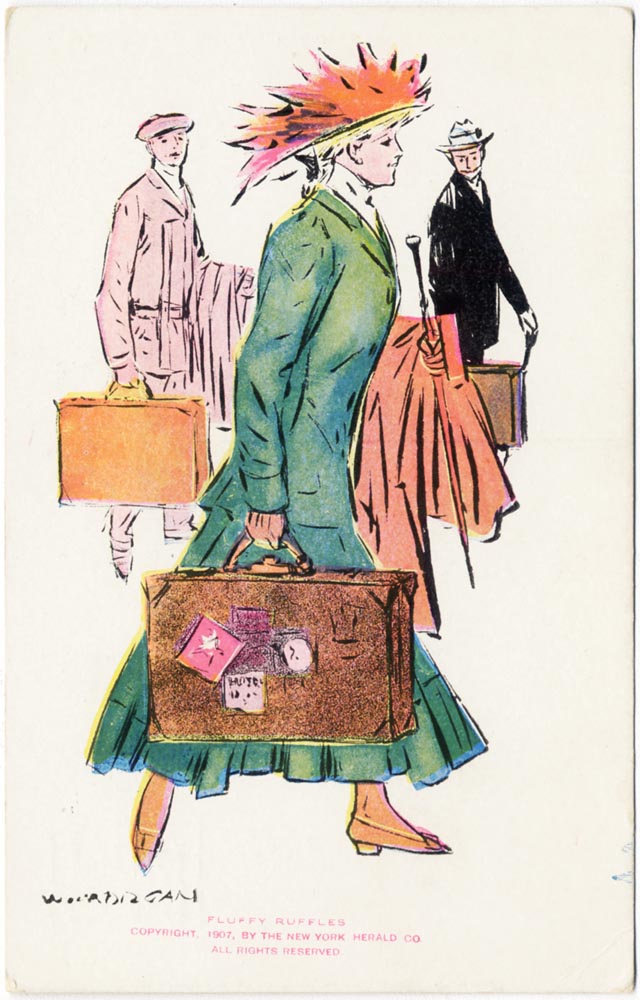

“Bah, for Mr. Charles Dana Gibson,” declared the Spokane Press in early 1908. Who needs the signature Gibson Girl anymore. “Miss Fluffy Ruffles is the newest type to which all the girls aspire.”1 The job-hunting, resourceful, and decidedly independent heroine became a national sensation shortly after her Feb. 3 premiere in the New York Herald. Fluffy was a pioneering woman in the workplace battling a reversal in fortune by making weekly tries as a journalist, florist, schoolteacher, dairy maid, waitress and more. The full page Sunday story was conceived and told in comic verse by a professional woman of note herself, the children’s and mystery writer Carolyn Wells. Herald illustrator Wallace Morgan dramatized the tale in vignettes that seemed to channel Charles Dana Gibson’s genteel magazine style. The series ran until early 1909 and quickly a multimedia juggernaut. The early episodes of her job-seeking stage were reprinted in book form before 1907 ended. Within six months of the launch The Herald started contests to find real-life Fluffy Ruffles that migrated to partner newspapers around the country. Paper dolls, chocolates, sheet music, branded hats and suits, even cigars, soon carried the Fluffy Ruffles brand. A 1908 Broadway musical production would travel the country until at least 1910, a year after the strip itself had ended.

The absence of the Fluffy Ruffles craze of 1907-1908 in standard comics histories is a major miss and hard to fathom. Wells and Morgan’s serial is one of the clearest examples of the complex ways that newspaper strips shaped an emerging ecosystem of mass media, modern taste-making, merchandising and even pop sociology from early in newspaper comics history. Just as social history alone, Fluffy Ruffles was among the first working girls portrayed in modern pop culture.2

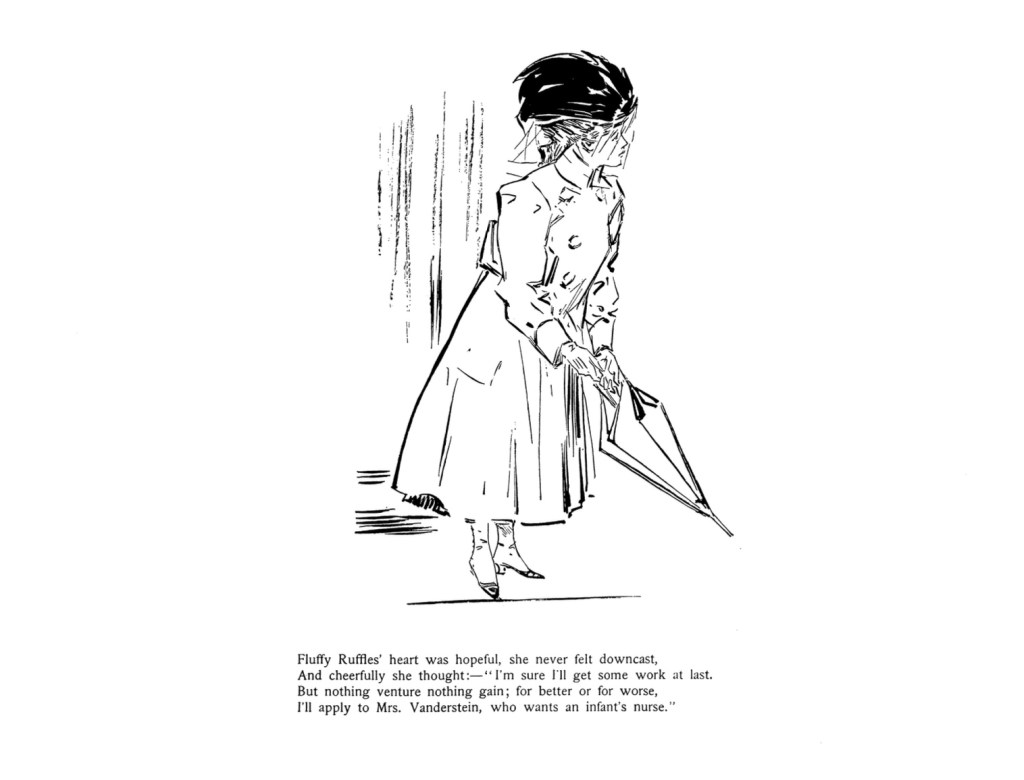

Wells signals Fluffy as a break from delicate feminine stereotypes at the start. The once-rich Miss Ruffles has a financial fall. “But did she have hysterics, or throw a fainting fit?/No, plucky Fluffy Ruffles was not that sort a bit.” No, indeed. Our Fluffy rejected the delicacy of Victorian womanhood by eschewing their keywords. She suffered neither the “hysteria” nor the fainting fits associated with precious late-Victorian middle class femininity, but instead had “pluck,” the resourcefulness and ambition of countless dime novel heroes.

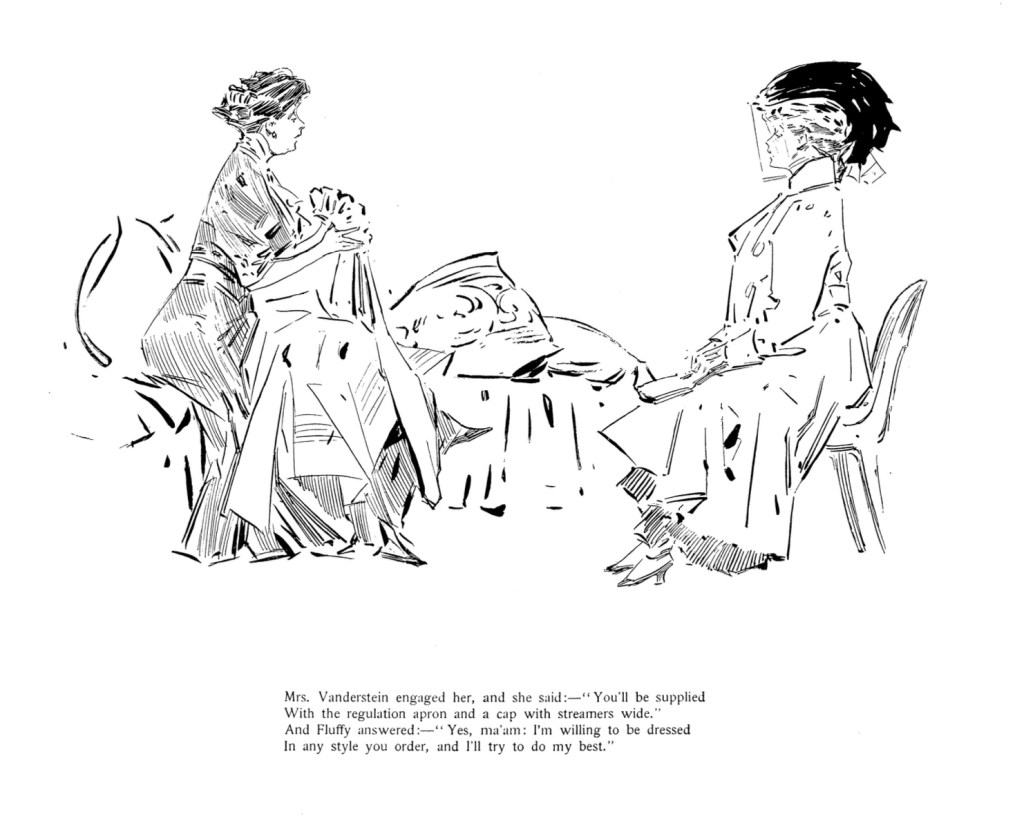

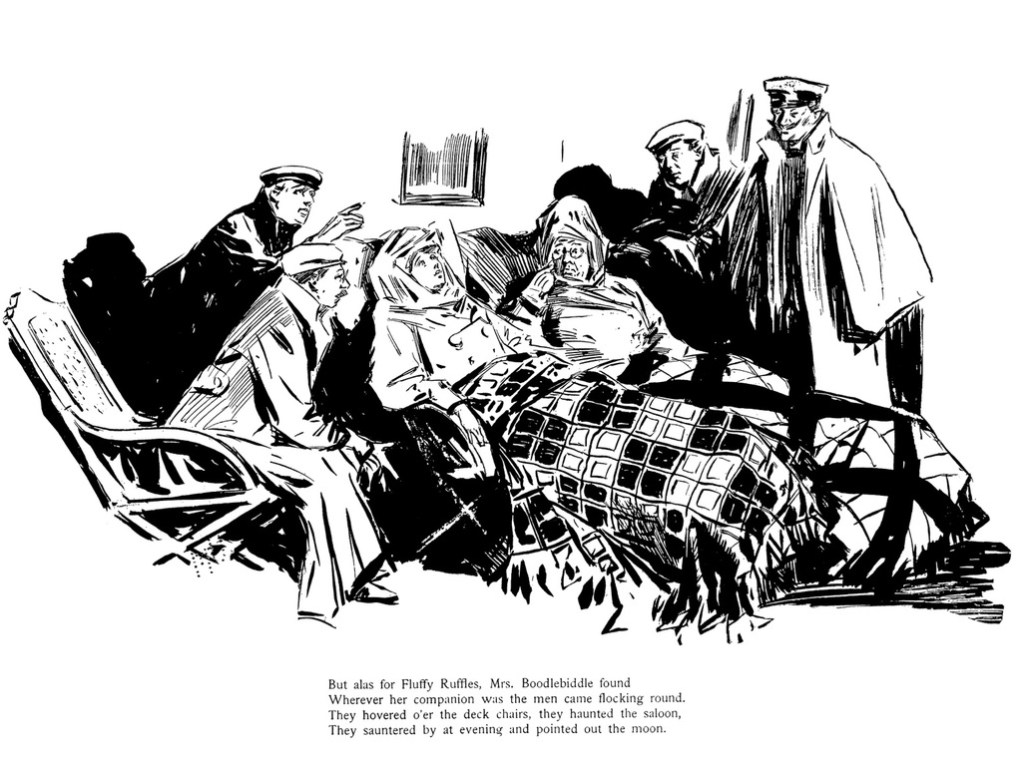

And yet, in the opening months of Fluffy’s adventure into the work world, her own feminine attractiveness is her biggest enemy. Whether trying to become a florist or traveling companion, dance instructor or waitress to a rich family, she runs into the same problem. Men swarm her with attention. Inevitably, employer frustration, feminine jealousy or Fluffy’s own discomfort ends the job. “To have a girl like that around would never, never do,” muses the florist. While a regretful wealthy employer “wept on Fluffy’s shoulder as they said their sad goodbys-/Yet she couldn’t have a waitress with such fetching violet eyes!” While Wells did not seem willing to engage in genuine social satire, it is clear that while Fluffy may be ready for the world, the world is not wquite ready for Fluffy.

The series evolved by the end of 1907, as a new inheritance saves Fluffy from the work world. For the rest of the run, she becomes a traveling dogooder who solves social problems and rescues the unfortunate. Fluffy sees a woman struck by a speeding car, pursues the rich owner and extracts payment for the fallen lady. A starving artist is faint from hunger so she buys his paintings and uses her fame to attract more business for him. She uses her wiles and ingenuity to rekindle an aging husband’s ardor for his wife. When Fluffy tries “settlement house” work to educate factory working girls, the class is wildly popular becasue the girls want to learn mainly about her clothing styles. And she takes ownership of her celebrity and famous charms, lending them to a local armory commander who is having trouble marshalling his tropps for drills.Her kind face is even powerful enough to soothe an escaped raging zoo tiger. In essence, Fluffy Ruffles settles into being a kind of genteel super-heroine, resolving incidents, reversing misfortune, inspiring good deeds. But the essence of Miss Ruffles is that she is relentlessly unruffled. Her beauty, poise, confidence and optimism stand fast against many circumstances of modern city life she encounters.

Fluffy Ruffles’ immediate appeal is unsurprising. The character idealized a tension in early 20th Century America over women’s changing social roles. The series imagined a woman departing old gender restraints without necessarily breaking them. Fluffy was entering a 1907 America where middle class women were moving out of the domestic sphere into public life in many ways: as Progressive-era social reformers, prohibitionists, suffragists, or even as secretaries and teachers in a new century of much bigger business and government. Fluffy registered these changes but in a different, perhaps lighter tone.3 She engaged emerging careers for women with ambition, competence and even resourcefulness. Always upbeat, never discouraged, Fluffy even embodied many of those “plucky” traits associated with an upwardly mobile American male type. Yet, her ambition never comprimised her femininity and attractiveness. In fact, she was thwarted in the end, not by sexism or unsuitability, but by her own damned beauty. This was a comforting rendering of an evolution in the American woman, encouraging without being threatening. Which is to say, Fluffy Ruffles was also pioneering for a new mass media one of its central cultural roles. to mythologize change, smooth its sharp edges, weave comfortable narratives around social transformation.

And let’s not forget the randy boys around Fluffy, who represented the other side of this gender upheaval. The newspaper comics had been skewering a new generation of horny clerks and rising young professionals for years. The first regular daily strip, The Importance of Mr. Peewee (1903, H.A. MacGill and others) cast the modern man-on-the-make as a toddler-sized braggart desperately trying to impress unaccompanied city gals. Jimmy Swinnerton’s tomcat cad, Mr. Jack, got thumped by his wife weekly for his relentless carousing. The Hall Room Boys (MacGill, 1906-1923) were penniless pals Percy and Ferdie who tried to fake their way into the graces of uptown women. Fluffy’s crowds of admirers clearly represented a more refined and restrained male desire. But make no mistake. The pheromones were flying in the comics pages in this first decade, as the medium registered a new sexual dynamic on the city streets, men and women finding one another in the anonymous urban village.

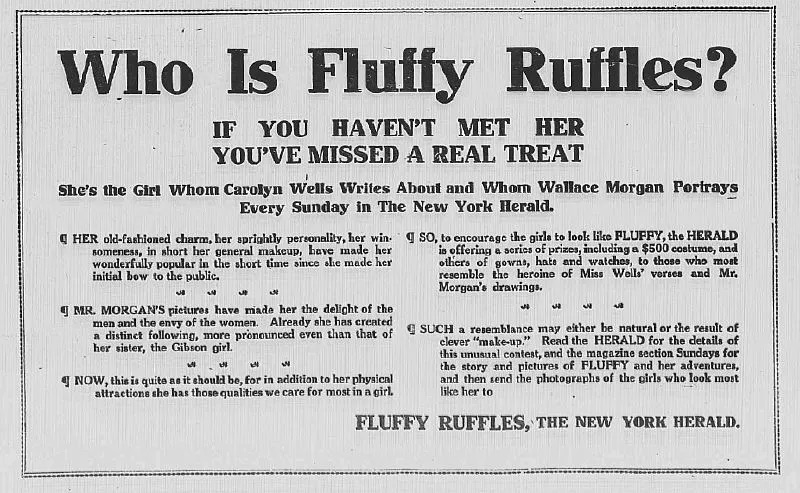

Both the reading public and the emerging media and marketing machines of 1907 soon rehearsing roles that they would play in these kinds of modern popular “crazes” throughout the coming century. When the New York Heralds asked “Who Is Fluffy Ruffles?” and started a contest to solicit photos of real life lookalikes, the answer seemed deliberately vague, as much about style as specific traits. Papers around the country followed suit. One of the most aggressive promoters. the Pittsburg Press, claimed its search for girls with “the Fluffy Ruffles idea” was so popular that men were submitting poetic odes to their new ideal. “Miss Fluffy is the most popular young person in the country today…she really has set the hearts of the men afire with her fluffiness.”4 And the Fluffy trend represented a notably self-conscious cultural shift away from the last feminine cartoon ideal from Charles Dana Gibson. The Pitzer Dept. Store Company declared in an ad for Fluffy-inspired goods “Miss Gibson Outdone By Miss Fluffy Ruffles.5 Echoing news stories and ads throughout 1907, the notice argued “She is more popular than ‘Miss Gibson Girl’ ever was.”

What exactly was this “Fluffy Ruffles idea” anyway? Carolyn Wells’ character was outlined loosely enough in verse to invite a range of interpretations and varying emphases in news reporting, merchandising and media criticism. The adjectives surrounding Fluffy in the press were as voluminous as her signature ruffles. Describing the Herald’s search for real world Fluffies, The Lexington Herald Ledger insisted, “It’s not a beauty contest. Its aim is simply to find the best example of the sweet, simple, wholesome, but essentially well-bred and ideally portrayed by the artist.”6 The NY Herald itself positions Fluffy as a “sister” to the Gibson girl and a new ideal of American womanhood that doesn’t discard the old: “Her old-fashioned charm, her sprightly personality, her winsomeness, in short her general makeup.” “Also, they argue, “there is the tilt of the head that suggests independence,” The Herald said in one of its promotions.

Oddly enough, Fluffy’s own co-creator and stylist, Wallace Morgan, may have been her least enthusiastic admirer. Recounting the genesis years later, he dismissed the character as a “blonde scatterbrain” and a “featherhead.”7 Some fans seemed to agree. A member of the Topeka chapter of her fan club, told the Lawrence Weekly, “Oh, we are just Fluffy Ruffles, just frivolous.”8 Broadway took Fluffy more seriously, however. In 1908, a musical built around the character described Fluffy as “buoyant and confident and always lands on her feet.” Indeed, the play, which starred Broadway regular Hattie Williams, even gave their Fluffy a political edge. The New York Times’ reviewer was surprised by an odd interruption to the usual musical fare in Act II – “an oration on women’s suffrage.”9 Wells and Morgan had offered a directional outline of a new generation of young women that different audiences and media extensions could fill with their own colors.

Following the example of cartoon merchandising successes like The Yellow Kid, Buster Brown and Foxy Grandpa, the Herald lent Fluffy’s character to everything from chocolates to cigars. But fashion is where the Fluffy Ruffles persona intersected with the biggest 20th Century juggernaut of all, the consumer economy and culture. Morgan had endowed the character with practical low-heeled shoes, a feathered hat and what he described as “a little frilly jacket” that served as a style guide for countless Fluffy Ruffles suits and accessories advertised aggressively in newspapers around the country. The Fluffy Ruffles craze arguably marked a turning point where an entire genre of comics were targeted to women and took a more self-conscious role shaping popular styles. And the series became increasingly reflexive, making Fluffy’s fame and style-setting influence a part of her fictional character. One Sunday episode dwells entirely on Fluffy’s Easter bonnet, which she ends up DIYing from an “untrimmed hat,” “‘A bow, a feather—something here’…The result was a creation (as the picture makes you see.)” Wells and Morgan knew they had a fashion icon on their hands. And perhaps for the first time, comic strip merchandising reached beyond simple toys and endorsements and into the personal everyday style of Americans, an opportunity to buy into character cosplay.

Which also points to something deeper at work here. Wells and Morgan were establishing important connections among fashion, “personality” and a rising culture of consumption. This popular series is starting to make the argument to an emerging cosumer culture that fashion mattered as a vehicle for self-expression. Material goods were emblems that made concrete the vagaries of whatever that “Fluffy Ruffles idea” was supposed to be. And this linkage between inner qualities and expression through acquisition was only beginning to take shape in 1907 as a core principle of a consumption economy and culture. In the comics pages, that genre of fashionable, lightly feminist heroines essentially starts with Fluffy and continues in Nell Brinkley’s masterful continuations of the verse+vignettes format during WWI and after (some of which Carolyn Wells wrote). And into the 30s and 40s, Gladys Parker and Jackie Ormes explicitly straddled the worlds of cartooning and fashion design. But across these decades and artists, their work contained the same implicit argument – that clothing was a legitimate, nuanced expression of self.

Like the many fictional stars and real life celebrities that followed in the new century, Fluffy was loosely enough drawn to allow multiple audiences to project onto her what they would. Her basic outlines were directional, however: an evolutionary break from the past, a new woman of worldly confidence and competence, optimistic and resourceful, embodied as much by her personality and style as specific traits. And she was part of a turn of the century moment in which the culture sought new social types that seemed better suited to a mass manufacturing economy, an urban/suburban environment, novel patterns of bureaucratic and industrial work. If the adjectives floating around Fluffy Ruffles felt indistinct it was because they had to be. She was resourceful and adaptable in an environment of change that demanded those skills and a certain fluidity of identity. This was a different world of city connections that were based less in familiarity than in signals like dress, dialect and manners. The comics were uniquely positioned to address all of those cultural anxieties because their skill set was lampooning types, skewering manners, decoding appearances, trading in dialect, let alone dwelling on a single persona day after day, week after week

In his famous essay on “‘Personality’ and Twentieth Century Culture,” Warren Susman argued that the 20th century experienced a radical shift in conceptions of self from “character” to “personality.”10 The 19th Century had been grounded in the moral notion of “character,” usually associated with the values of work, duty, citizenship, democracy, manners, integrity, manhood. Sometime in the first decades of the 20th Century increased calls for a “new man” to cope with relentless modern change surrounded the term “personality.” In a new world of cities, anonymity, appearances, standing out from the crowd was a preeminent value of the emerging culture of “personality.” Around it we find different terms like fascinating, individuality, self-development, magnetic, creative, dominant, forceful. Concepts like self-realization begin replacing self-sacrifice. “The social role demanded of all in the new culture of personality was that of a performer,” writes Susman.11 Subsequently, Jackson Lears further developed this idea of a new modal self for modern American, arguing that a modern psychological vision of self that reinforced emerging needs of consumerism. “As economists conceived an upward spiral of production and consumption powering endless economic growth, psychologists imagined a fluid, vital self pursuing a path of endless personal growth,” he argues.12 (Literary History of America, p. 453).

To understand why the comics medium in the first two decades of the 20th Century enjoyed such enormous popularity and proliferation across other media, it is critical to appreciate how much it provided a language for dramatizing social change in ways that also diffuses some of its most frightening realities..

- “Fluffy Ruffles Girl Is the Real Thing This Season,” The Spokane Press, Feb. 6, 1908 p. 3. ↩︎

- In the last few years, a few Women’s Studies scholars have surfaced Fluffy as an early depiction of middle class women entering the workforce. And some fashion history notes that her style became a sensation in 1907-1908. The general histories and anthologies of comic strips, however, overlook Fluffy Ruffles entirely. ↩︎

- Outside of the middle and upper classes, there were of course, millions of “working women” in 1907, mainly among emigrees and the manual labor class. ↩︎

- “Men Write Poetry About Fluffy Ruffles,” Pittsburgh Press, Oct. 19, 1907, p. 4. ↩︎

- Bristol Herald Courier, Sept. 19, 1907, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Fluffy Ruffles,” Lexington Herald Leader, Aug. 11, 1907, p. 9. ↩︎

- Douglas Gilbert, “Fluffy Ruffles Up-To-Date: Morgan Traces the Evolution of the Famous Girl of His Pen,” The Cincinnati Post, June 7, 1933, p. 11. ↩︎

- “It Is Now Miss Fluffy Ruffles,” Lawrence (Kansas) Weekly World,” Oct. 3, 1907, p.1. ↩︎

- New York Times, Sept. 8, 1908 ↩︎

- Sussman, Warren I. Culture as History: The Transformation of American Society in the Twentieth Century. New York: Pantheon, 1984. ↩︎

- Ibid,p. 280. ↩︎

- Lears, Jackson in Sollors, Warner and Greil Marcus, eds. A New Literary History of America. Cambridge: Belknap, 2012, p. 453 ↩︎

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Wonderful article!

And this explains one of my favorite 78s the Fluffy Ruffle Two-Step that belonged to my grandparents: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Ucwd3BMoHM