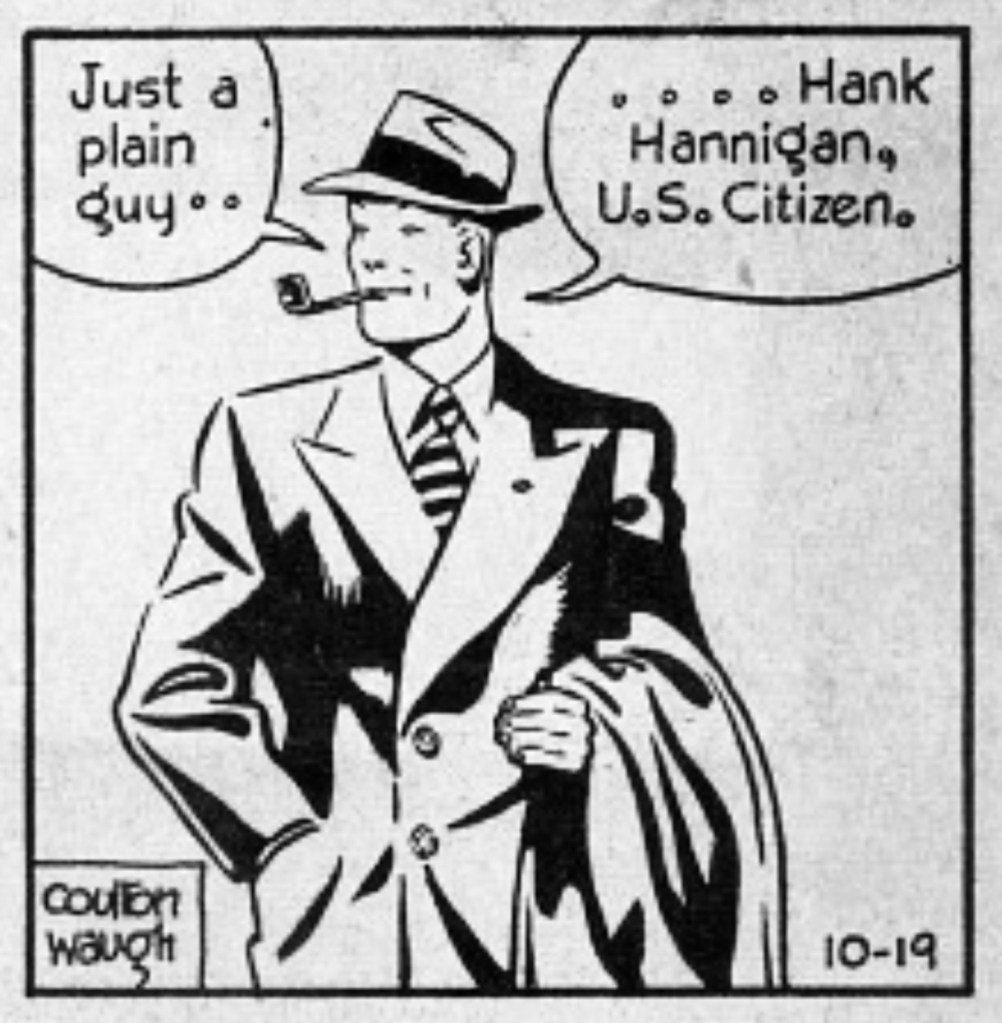

A WWII veteran amputee who doesn’t want to journey (or save) the world. Just a grease monkey who yearns to get back to the garage, marry his sweetheart, and figure out what he and his pals’ great sacrifice really meant. That was Hank Hannigan, the titular, unlikely hero of the short-lived 1945 comic strip Hank, which creator Coulton Waugh conceived as an answer to traditional adventures. “To get a new character I go into the subways and actually draw them,” he told Editor and Publisher before Hank’s April launch. “I want the people of America to stream into the strip.”

Waugh knew well the familiar notes of adventure strips. Since 1934, he had written and drawn Dickie Dare, after Milton Caniff left that strip to launch Terry and the Pirates. But Hank, was “a deliberate attempt to work in the field of social usefulness,” he said, and to incorporate an expressive design sense that he admired in the late George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. The editors at the strip’s host newspaper, New York’s populist/progressive PM, promised that “The new strip works out interpretive techniques that are as new and different in comic strips as some of those developed by Crockett Johnson in Barnaby,” which PM had launched two years before. For only eight months, Waugh succeeded in giving readers something that looked and sounded unmistakably different from the norm. Hank was packed with firsts. No comic had ever featured a character with a major physical disability. The strip included a regular Black character without whiff of minstrelsy. Its unvarnished view of combat veterans returning to civilian life also took an unabashed pluralist, progressive stand on what those soldiers fought to preserve. Despite its innovations, Hank is a forgotten strip that has been mentioned by historians more than actually seen or explored. And yet the time seems right to resuscitate a lost anti-fascist warrior.

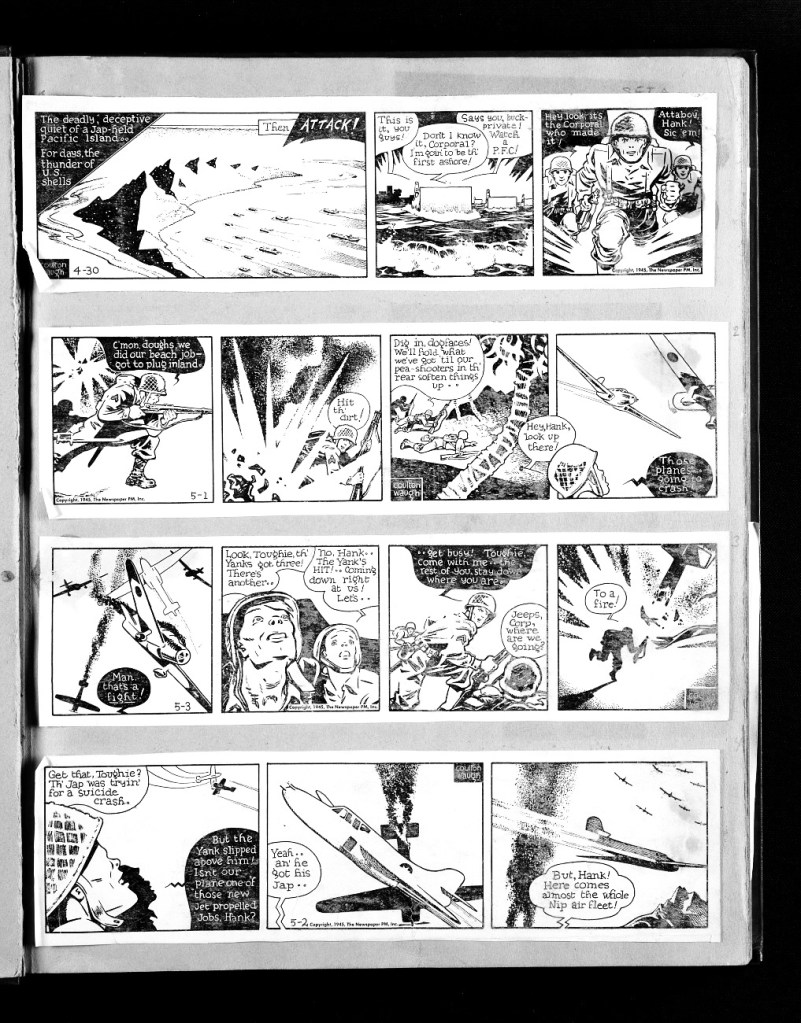

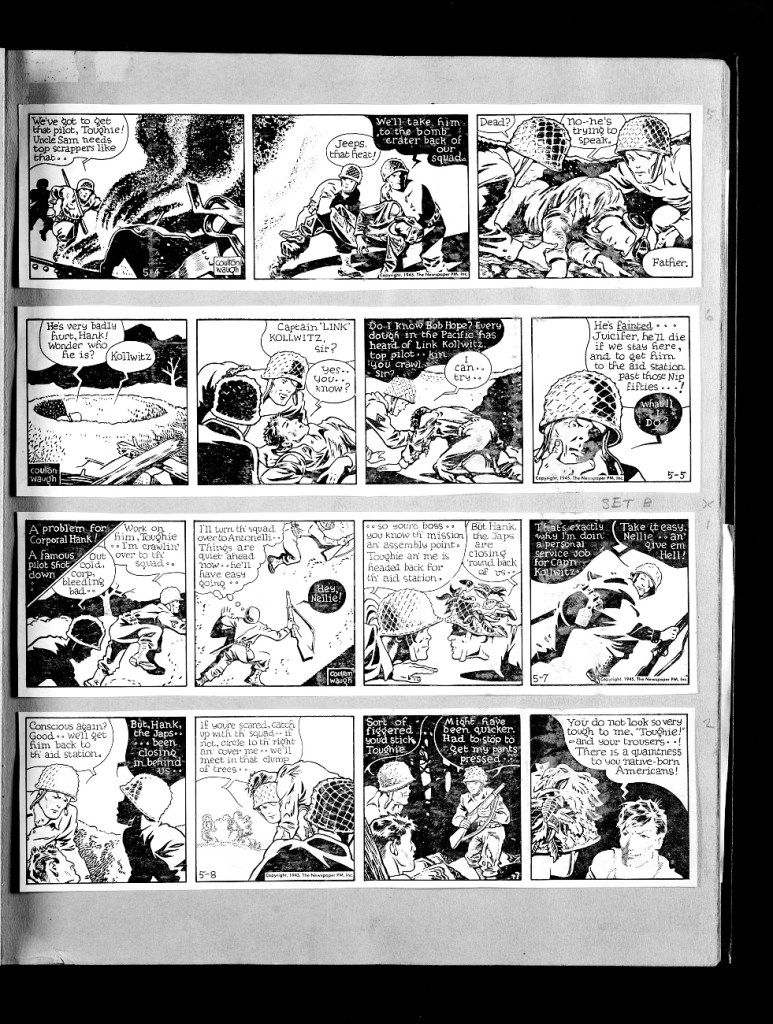

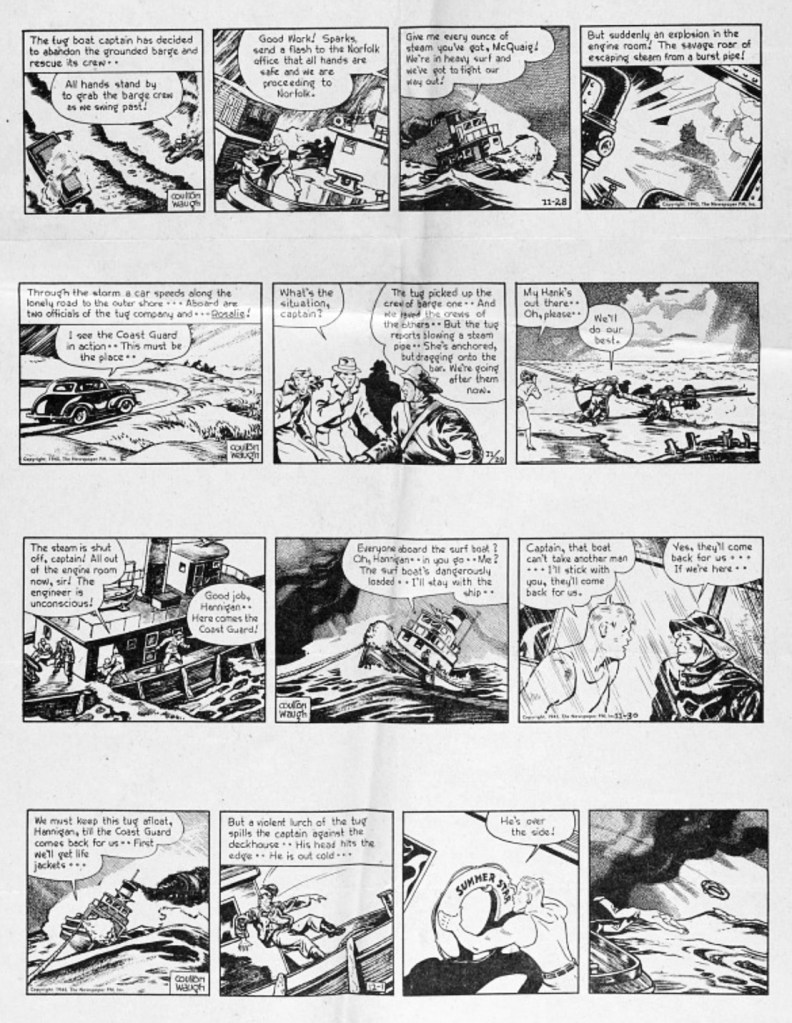

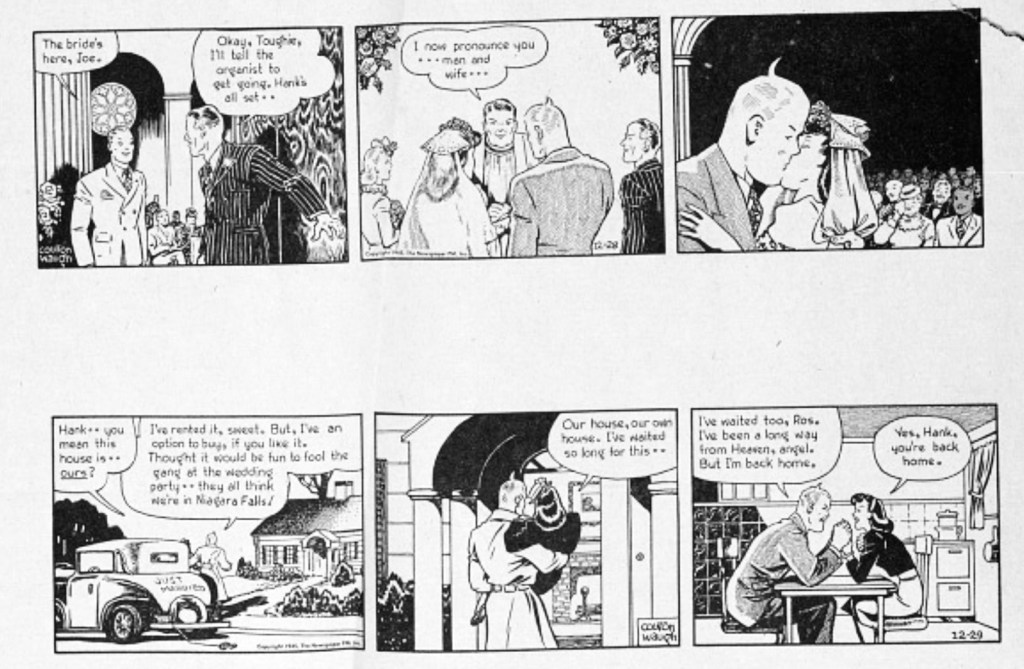

Hank has never been reprinted, and only stray panels and strips appear online. An unevenly scanned PDF of one of Waugh’s scrapbooks does include a patchwork of clippings and syndication proofs including most of the full run. Here are the first 8 days of the strip.

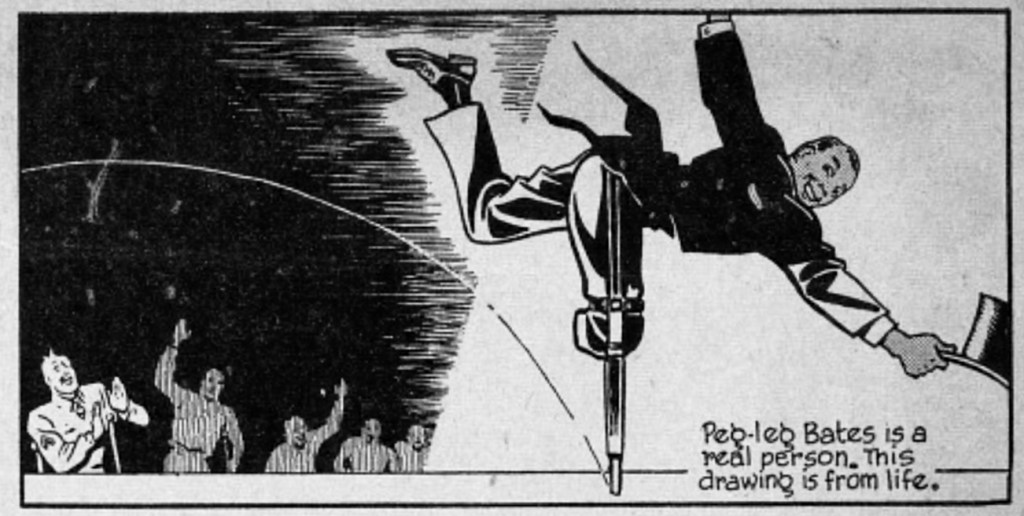

Starting in the Pacific theater late in the war, we meet Corporal Hank Hannigan in battle. In the course of things, he rescues a fallen flyer (the legendary Capt. “Link” Kollwitz), shows his native genius by outsmarting a Japanese sniper and gets blown up salvaging his squad. The strip pulls few punches. At the army hospital, Hank loses the lower half of his leg and Kollwitz dies. Depressed at the prospect of life with a prosthetic leg, Hank finds inspiration in a peg legged entertainer who turned his disability into a successful act.1

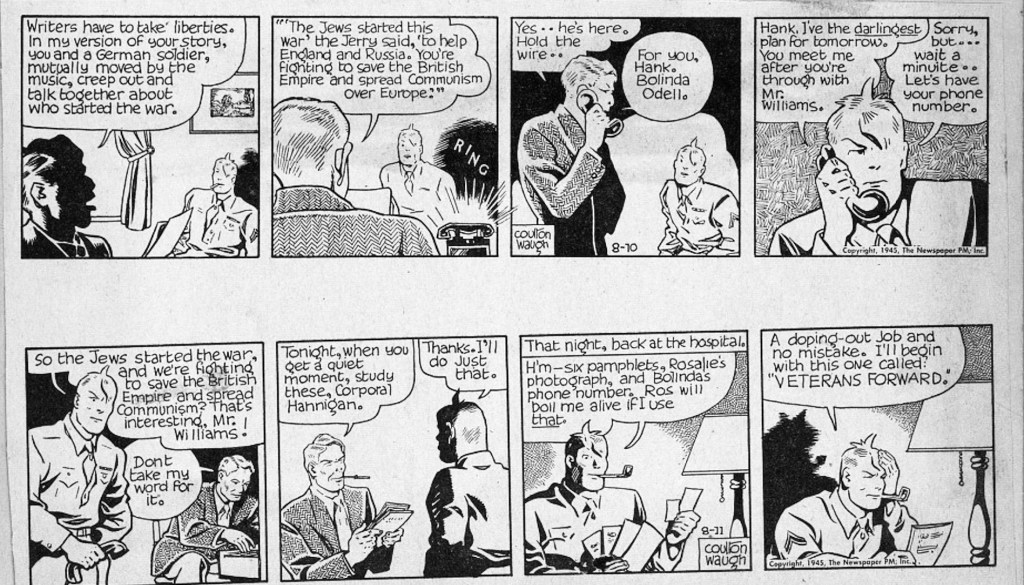

Hank was at its most didactic during the inaugural months when Waugh eagerly signaled the strip’s left/populist alignment with PM’s mission. At Hank’s launch, both war fronts approached Allied victory, and Waugh frames the effort as a war for pluralist democracy. Despite casual hatred for “Jap” and “Nip” foes, Hank’s heterogeneous squad is a roll-call of ethnic names and regional roots. Their rescuer is the “well-trained Negro” grunt Jerry Green, who becomes the first recurring Black character in a non-Black newspaper comic to avoid ethnic stereotyping. Even the late Capt. Killowitz was a German emigree who embraced Allied ideals. In sum, Waugh frames American democracy and identity are grounded in shared ideas and ideals, not ethnic or blood origins. And Hank himself emerges as a natural democrat. Even while claiming to be a grease monkey who lets “others do the thinking” Hank jerry-rigs a grenade throwing slingshot to neutralize a sniper. “That wuzn’t thinkin’. That was just my reg’ler stuff like fixin’ cars back home,” a knack for “doping things out,” he tells Kollwitz.

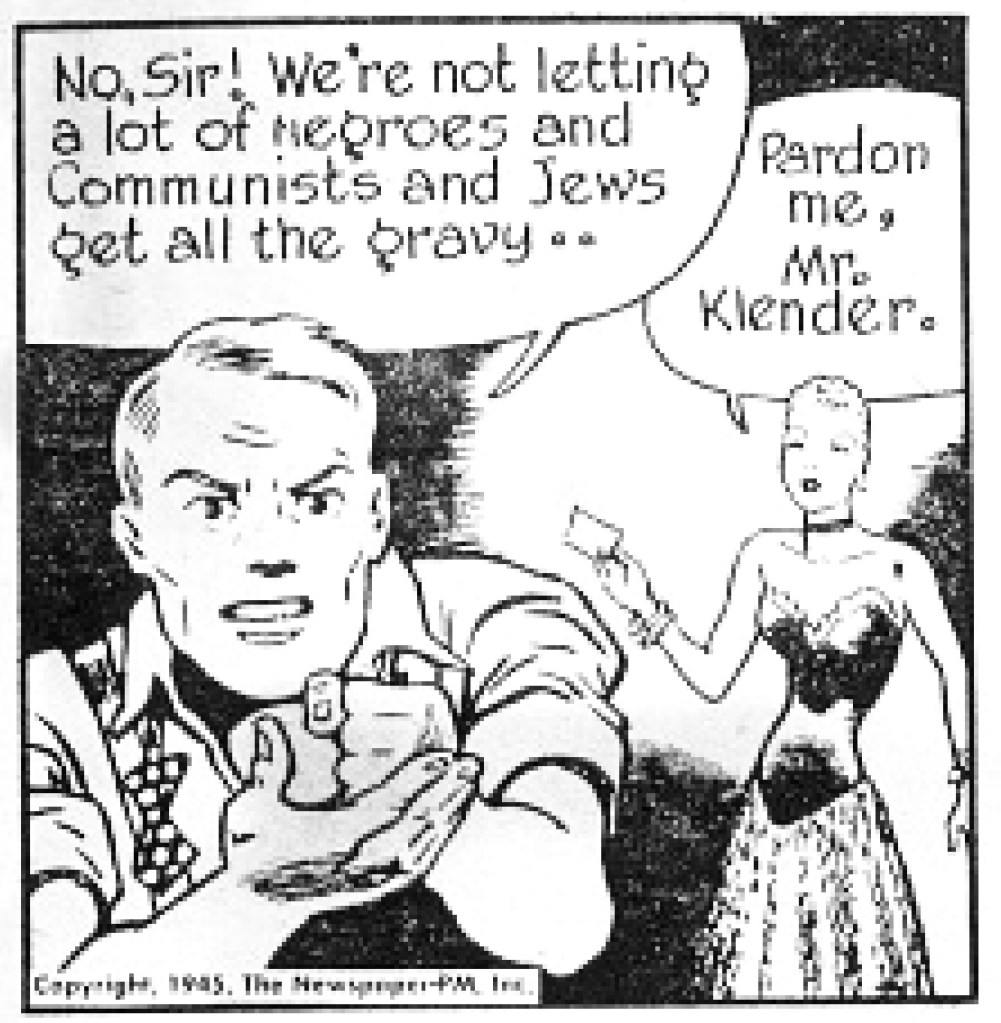

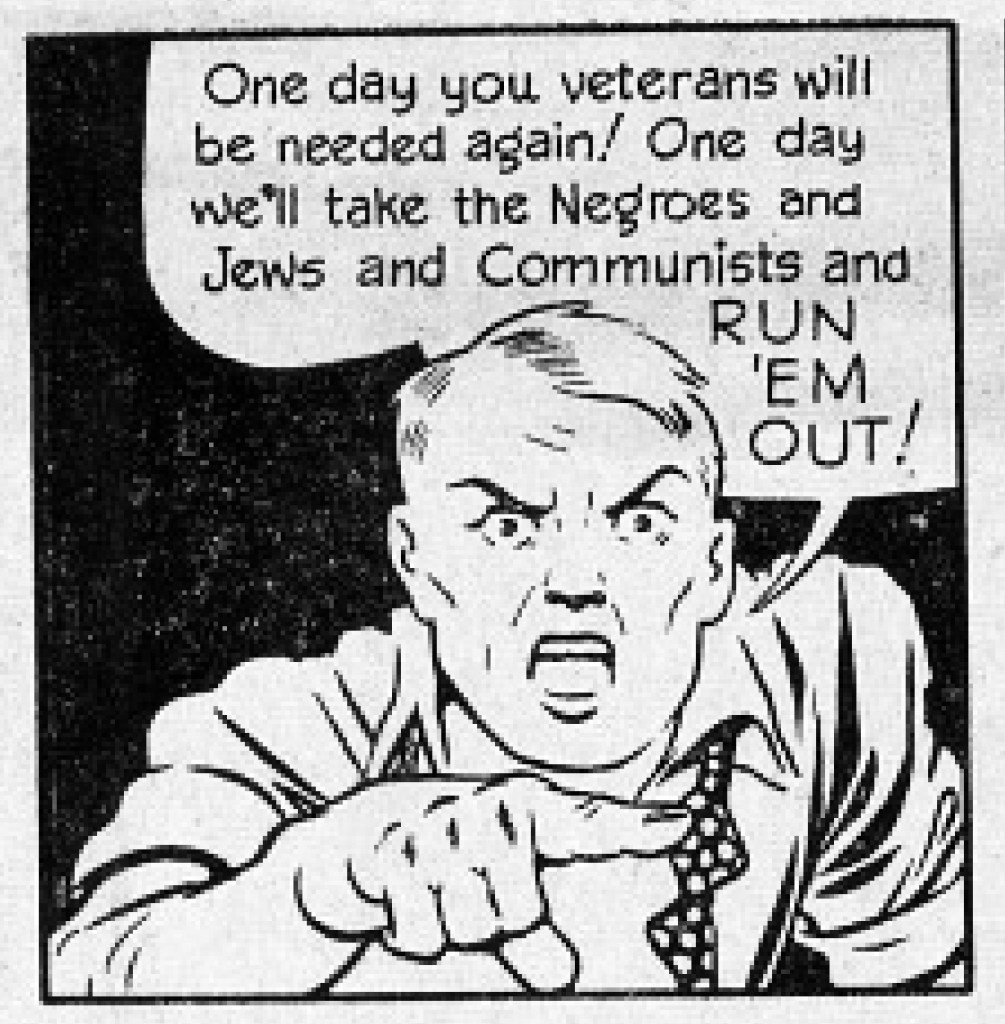

Hank will need that native ability to “dope things out” soon enough. The departed Killwitz left behind a diary with thoughts about how “everyone should dope things out, that fascism could even happen at home,” Hank recalls. Soon enough, a “Veterans Forward” league of nationalists tries to co-opt Hank into being their spokesman. Ultimately, Hank and a journalist pal infiltrate and expose the conspiracy as well as its racist nativism. “One day, we’ll take the Negroes and Jews and Communists and RUN ‘EM OUT!” one rally speaker barks out from a panel. Waugh was fictionalizing a storyline that PM’s own journalists reported at the time about secret connections between European fascism and American political and industrial factions.

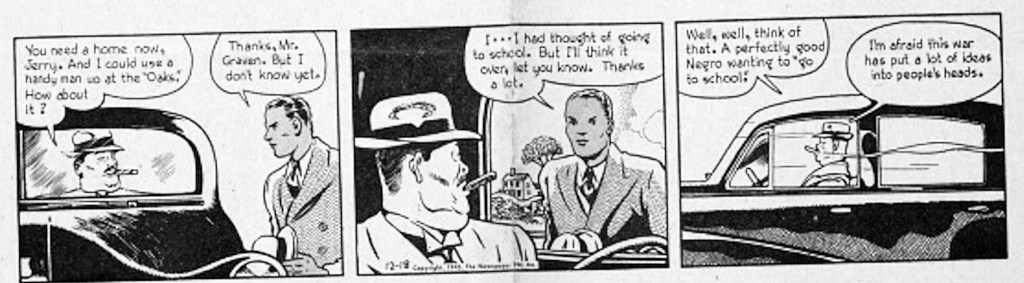

The strip took on racism a bit more obliquely. The heroic savior of Hank’s squad, Jerry Green, returns with college ambitions. A rich landowner offers him a job as handman for his estate. When Jerry politely declines, the cigar-chomping white man grumbles, “Well, well, think of that. A perfectly good Negro wanting to ‘go to school.’ I’m afraid this war has put a lot of ideas into people’s heads.”

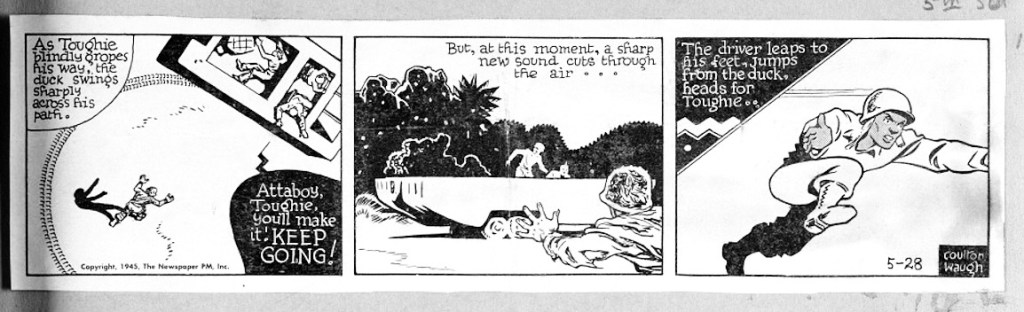

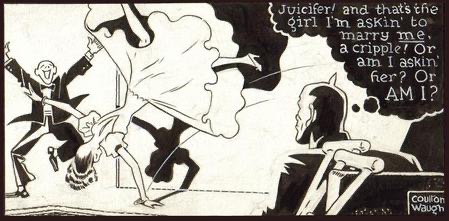

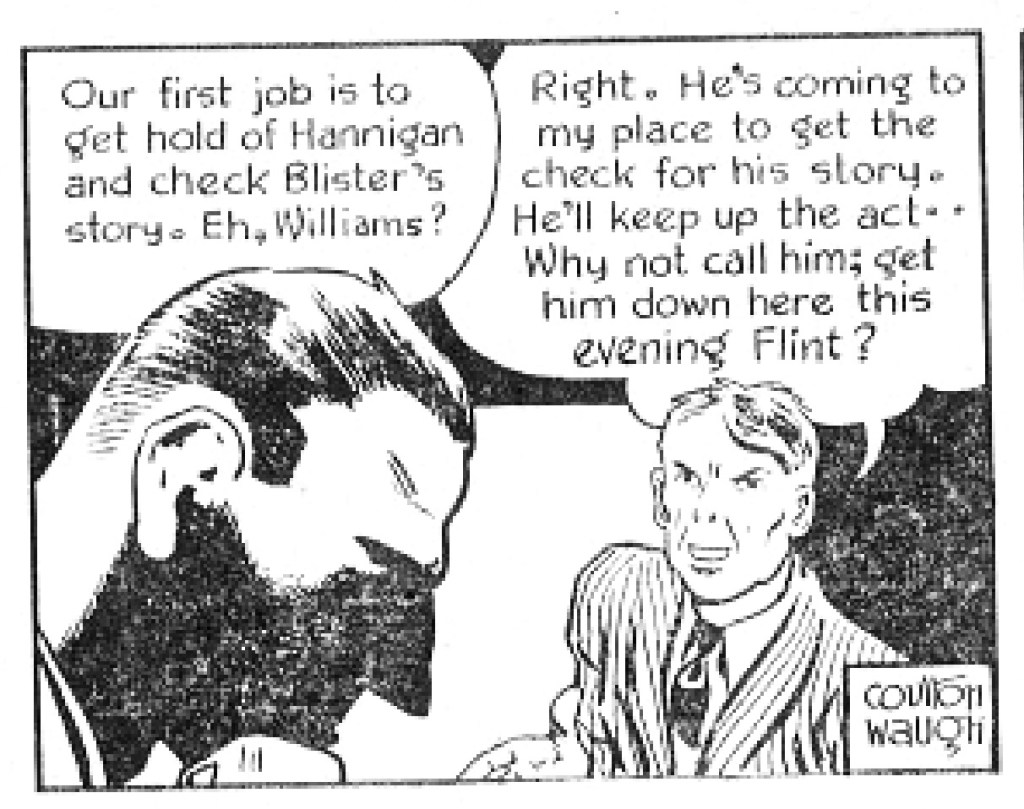

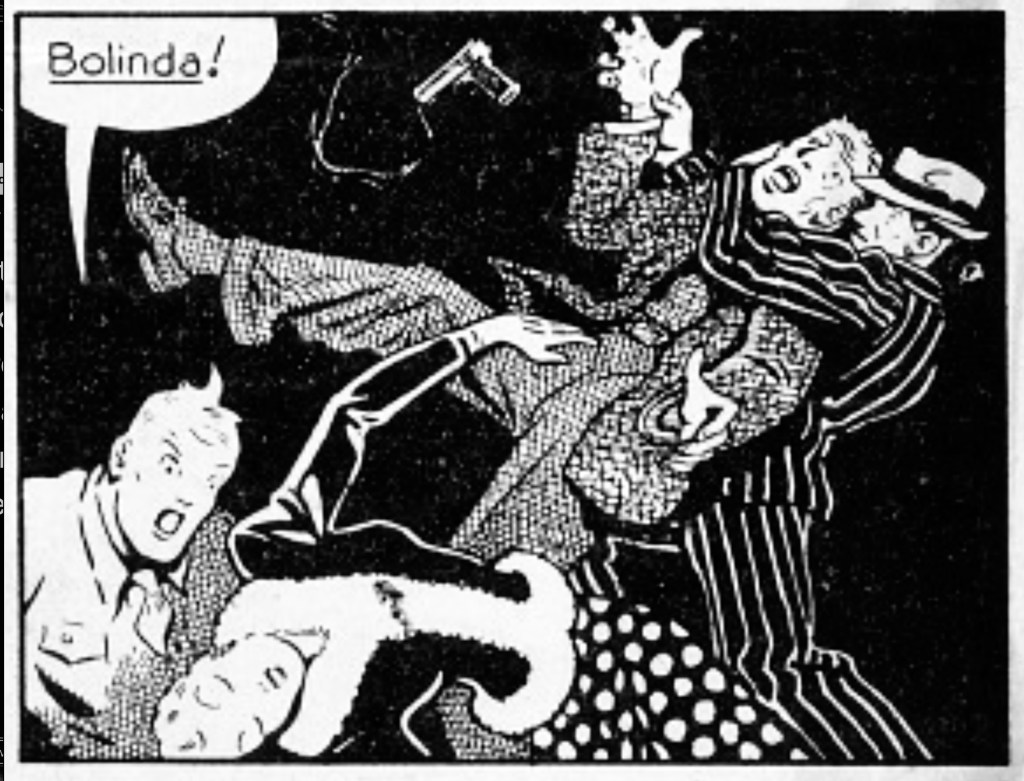

While Waugh lathers on the populist didacticism pretty thick in Hank’s first months, he leavens it with genuine intrigue and action. Woven into the anti-fascist conspiracy is a wonderfully drawn femme fatale who falls for Hank and a flurry of romantic missteps with girlfriend Rosalie. More impressive was the artist’s graphic experimentation. Waugh had a clean thick-lined style and use of deep shadows that seemed to channel the WPA poster art of the 1930s. He used light dabs of shadow to define face and clothing. His cityscapes were minimalist but precisely outlined, again, more by shadows than detail. Individual panels often carried a poster-like punch. His characters might speak directly to the reader with fist-pounding certainty and Soviet poster-art vibes. And Waugh loved playing with patterns – stripes, mottling, polka dots – with some eye-popping spotting around his panels. He even played with typography and speech balloons. His sculpted lower-case lettering often went white against a black balloon. Overall, he achieved an adventure strip style that stood apart from Roy Crane’s cartoony approach in Buz Sawyer, Alex Raymond’s Rip Kirby photo-realism and blotchy chiaroscuro of Caniff’s Steve Canyon.

About halfway through Hank’s short run, both Waugh’s ideological flexes and design flourishes settle down along with the storyline. A series of familiar miscommunications, missing communications and misinterpretations send Hank and Rosalie on a twisty journey towards the marriage that ends the strip at the end of December 1945. Believing mistakenly that Rosalie has fallen for a rich rival, Hank takes to sea as a tug boat mate. The ship gets swamped; Hank jumps overboard to save his unconscious Captain; then he himself gets saved from the storm, leading to a romantic reunion and Hank and Rosalie’s hometown marriage in Trueburg, N.J. (Yes, Trueburg). The sequence allows Waugh to exercise an uncharacteristic but beautiful naturalism in rendering the storm. Waugh’s father was a noted marine artist.

Waugh closed the strip at the end of 1945 with Hanks’s marriage and settling into a new home. For a strip that began so self-consciously contrary to comic convention, the ending was remarkably prescient of the domestication about to overwhelm adventure comics after the war. Waugh withdrew Hank, reportedly because of eyestrain, and he seems to have intended to wrap his story neatly in a bow. But for all of its novelty, the Hank strip did not have a clear path forward. Waugh was not a strong storyteller. None of his characters are engaging or well differentiated. The dialogue is hackneyed, the politics two-dimensional. The art, however, could be quite striking.

Hank was an interesting experiment both in design and messaging that recalls a moment of “Popular Front” coalition that may be relevant today. Its politics, and even its aesthetics, extended a partnership among the radical left and liberalism against the common enemy of fascism in the late 1930s. While often intellectual in leadership and tone, the Popular Front tried to appeal to working class Americans in its support of Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. Stylistically, it is often embodied by the art of WPA posters and regionalist painting that celebrated labor, the wisdom of the common man, ethnic diversity and abstract appeals to a collective democratic identity.

The PM newspaper, founded by TIME editor Robert Ingersoll in 1940, worked in that spirit until closing in 1948. It rejected the advertising model to remain independent of corporate interests, although its beneficiaries included Marshall Fields III and others. PM took a strong anti-fascist line, opposed Jim Crow measures like Poll Taxes, and was often accused by the right of being a “Communist front.” PM called itself a “picture magazine” and featured hundreds of editorial cartoons by Dr. Seuss as well as photography by Weegee and Margaret Bourke White. Ernest Hemingway, Dashiell Hammet and Dorothy Parker were among many contributors. And, of course, it was also the original home of Crockett Johnson’s Barnaby. Coulton Waugh’s Hank fit right in. The strip embodied an enduring left/liberal idealism about finding in the American common man a native democratic impulse that can be married to more highbrow social justice ideologies. At the same time, Waugh and others in this Popular Front were looking for artistic styles that infused those ideals in everyday popular culture.

- As the panel suggests, the amputee entertainer was based on a Broadway headliner, Peg Leg Bates. The son of a sharecropper, Bates lost his leg in his adolescence from a cotton gin accident. He turned the handicap into feature act. Waugh’s panels depict the reported climax of Bates’ routine – a flying leap that lands and then spins upon his reinforced peg leg. ↩︎

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Peg-Leg Bates Gets a Cameo in Hank – Panels & Prose