Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy was created in the 1930s as a response to the romanticization of gangsters and declining respect for law enforcement. And throughout its run under the notoriously conservative artist made no secret of his disdain for many modern trends. In the 1950s when mania around “juvenile delinquency” dominated popular culture, Gould added to his famous rogues gallery a few of these teen terrorists. Most notable for its outright weirdness (even for Gould) are the 1956 episodes spanning Joe Period and Flattop, Jr., the son of one of Tracy’s most famous nemeses of the prior decade.

Continue readingCategory Archives: great moments

Napoleon: The Gentle Art of Everyday-ness

Clifford McBride’s portrait of the affable, accident-prone and corpulent Uncle Elby and his puckish oversized dog Napoleon is one of those great American comic strips that are about nothing. There is no adventure or much of an ongoing storyline to the Napoleon and Uncle Elby strip. Nor are there gags, verbal or physical, really. It is more a strip about everyday mishaps. Uncle Elby is proud of his new white suit, which an affectionate Napoleon meets at the the front door with muddy paws. Constructing a simple tent results in a tangled mess. Napoleon chases a fleeing rabbit, chicken, cat or whatnot (it’s a frequent theme), only to be chased by his prey in the end. Elby mows over one of his dog’s hidden bones, which conks him on the bean. Elby gets out of his car to open the garage door only to have it slam shut before he can drive through.

No, really, the action in the Napoleon strip is that banal and trifling…relentlessly…and apparently by design.

Continue readingPremiere Panels: Mandrake Materializes…Eventually

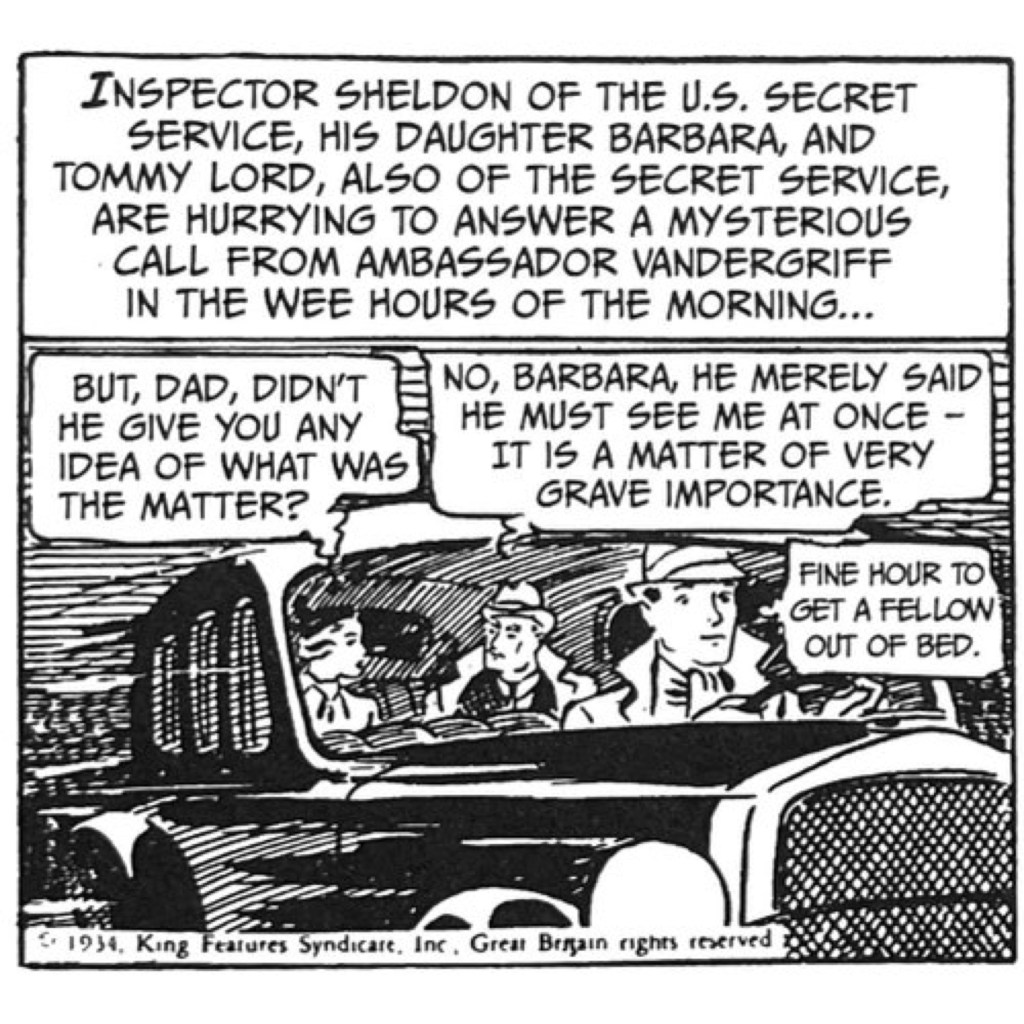

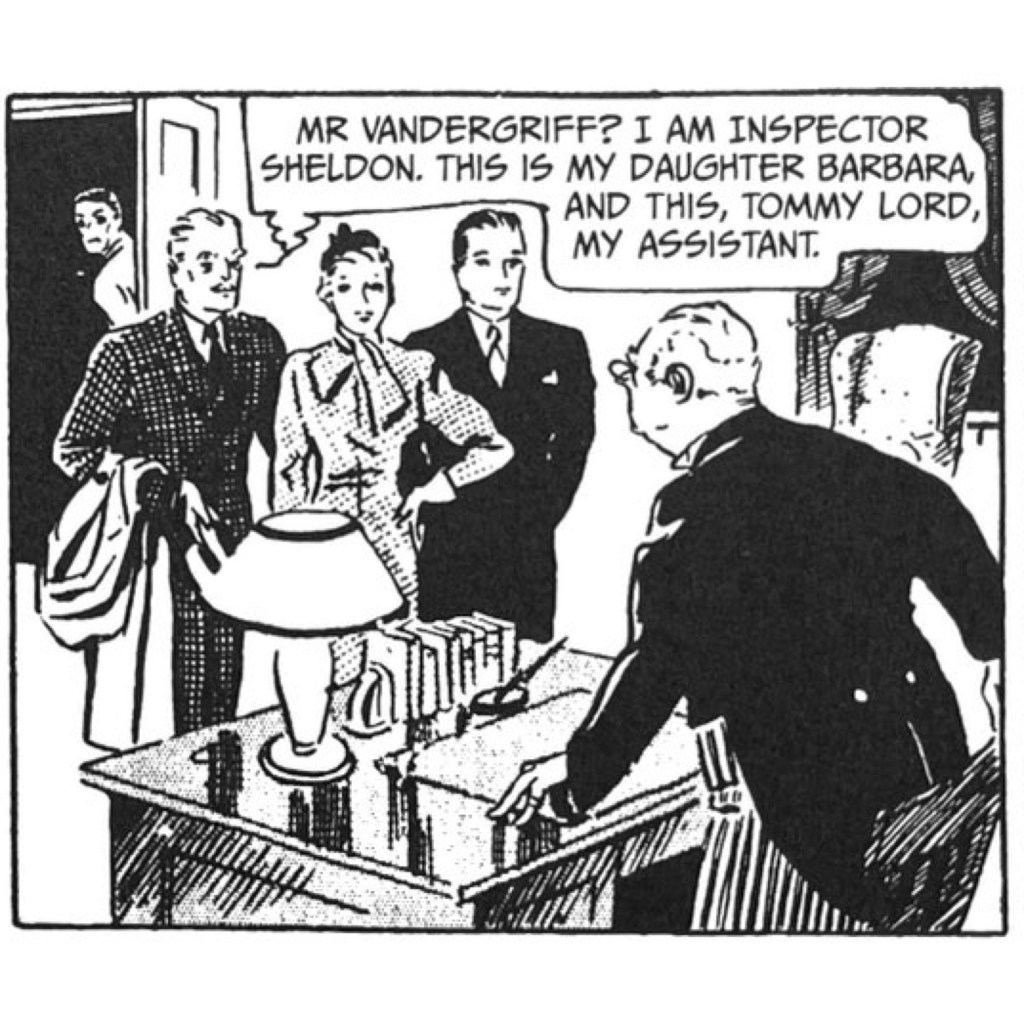

It took a full week of strips for the eponymous hero of Lee Falk’s Mandrake the Magician strip to make his grand entrance. June 11, 1934 was the first strip, which evokes some of the feel of a classic mystery wind-up. But on June 15, in what has to stand as one of the most unambiguously racist intros in pop culture history, Mandrake’s “servant” Lothar heralds the coming of his “master.” One doesn’t even know where to start here. Falk’s full bore colonialism is more fully and relentlessly explored in his later The Phantom series whose origin we covered here and whose fetishes we covered here.

For all of its weaknesses, Mandrake remains important both to comic strip and comic book history in that his is the first strip to move towards a super-powered hero. Mandrake’s “magic” is only nominally super-natural, in that it is based on the power of suggestion and influence over others’ minds. But it precedes the appearance of Superman by 5 years and aldo nods towards costumed heroism, which would be more fully introduced in Falk’s The Phantom.

Krazy Philosophy: Herriman At His Best

I have to admit that I have always admired and appreciated George Herriman more than I enjoyed reading him. The gush of praise for his work among American intellectuals in the 1920s was deserved and an important piece of pop culture history. My own favorite pioneer of pop culture criticism Gilbert Seldes famously declared Krazy Kat among the most satisfying works of American art in the 1920s. But I always have had trouble really getting into him. I have to dip in and out of Herriman, sip him briefly, in order to appreciate the full effect of his offbeat sensibility, linguistic play, hit-and-miss humor. The characters and their world, while wonderfully abstract and even surreal, also create a distance for me.

All that is to say that there are also times when the abstraction and subtle philosophizing in Krazy Kat really pops through and reminds me what a rich mind was at work behind the strip. This daily from 1922 is one example of the ways in which Ignatz and Krazy really do represent fundamentally different sensibilities that were quite relevant to the America Herriman was experiencing in the inter-war years. Ignatz, the worldly, materialist, the jaded modern defender of “realism” is not only opposed to Krazy’s more ethereal, romantic approach to the universe, he is moved to violence at the very sight of it. That to me is the most interesting dynamic in their relationship. It is not the difference between the two world views they represent. It is how they react to one another, Ignatz’s frustration and intolerance of the very existence of a Krazy-eyed view of the world, that activates the strip for me and speaks to its age. Most Krazy Kat dailies don’t end with a brick to Kracy’s head but instead Ignatz reaching for a brick as a primitive response to Krazy’s musings or poor pun or nonsensical quip. Herriman calls attention to our own response. Who are you? Ignatz or Krazy?

Like Krazy her/himself, I find that I am appreciating Herriman by taking it slow through his dailies and Sundays. Others that caught my eye are here and of course the discussion of Krazy’s gender here.

Death Becomes You: Tracy Villains Meet Their Fitting End

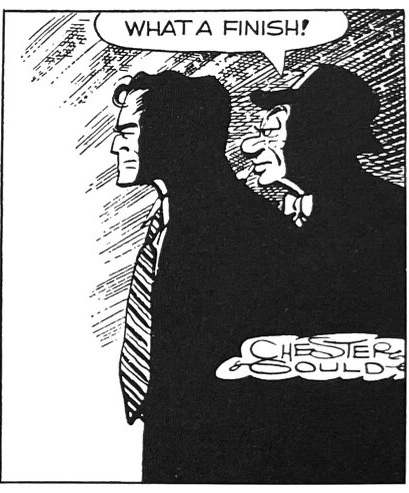

Retribution was Chester Gould and Dick Tracy’s model for justice from the beginning. The strip started in 1931 literally as a revenge narrative. Standing over the murdered body of his fiancé Tess Trueheart’s father, civilian Tracy swears vengeance on the killers. He quickly joins the police force, but the themes of retribution and conviction by poetic justice remained a hallmark of the strip across four and a half decade run. From the beginning Chester Gould unapologetically crossed the lines of good taste. By the late 1930s in criminals like The Mole, B.B. Eyes, Flattop, Pruneface and the like, Gould started using outward disfigurement as expressive of inner villainy. And the level of explicit violence and even torture in Dick Tracy was unlike anything else on the comics page, or elsewhere in pop culture for that matter.

The revenge motif was baked into the strip’s moral universe. Tracy villains didn’t just need to be sought, caught and jailed. They needed to be hounded and often tortured along the way. Many of Tracy’s prey ended up behind bars, but just as often they met poetically just ends. Gould turned the grisly, fitting deaths of villains into his own special kind of art. Here are some examples from the first two decades of the strip that highlight Gould’s dark talent for retributive justice and capital punishment Dick Tracy style. At these climactic moments we see most clearly the visual, moral and often bizarre world,

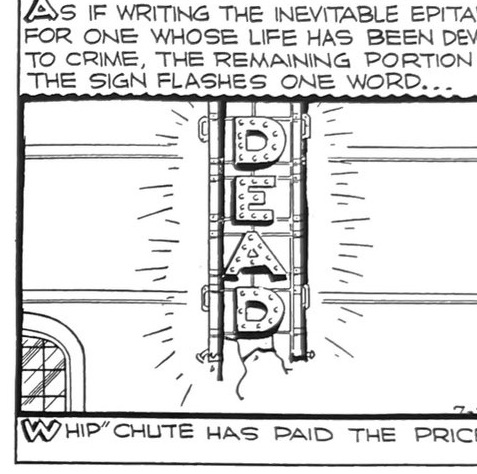

Final Curtain for Whip Chute – 1939

Subtlety was not in Chester Gould’s quiver. Here he triple underlines his irony.

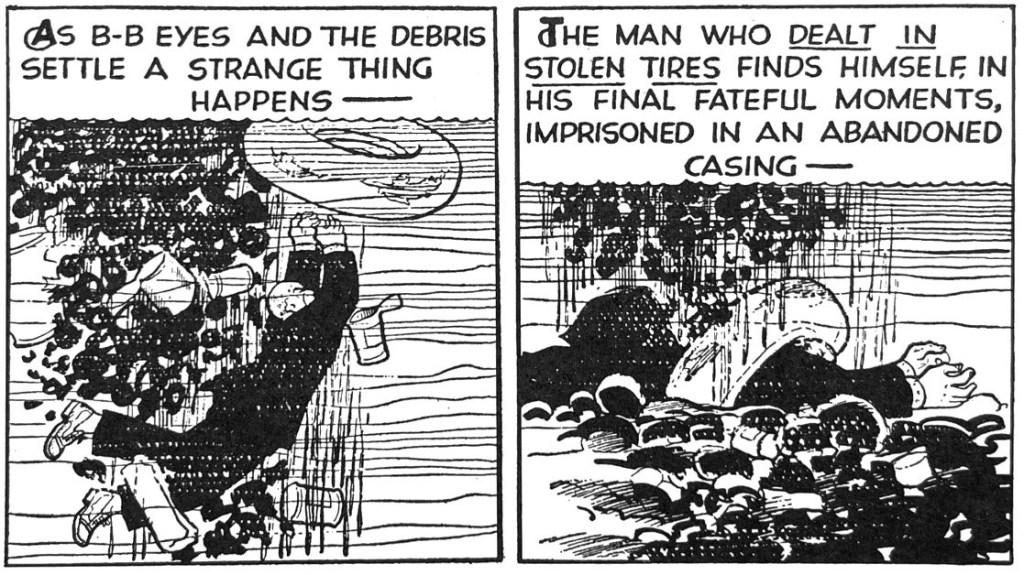

B-B Eyes Gets Dumped – 1942

More than anything, Gould loved to kill and humiliate Tracy villains in slo-mo. Here, B-B Eyes hides in a garbage barge in the final leg of a desperate flight from justice, only to get dumped, trapped and drowned. Gould had a special talent for using the panel. framing and zoom techniques to communicate feeling through his use of space. His signature tight shots on dead villains often conveyed the loneliness and claustrophobia of death itself.

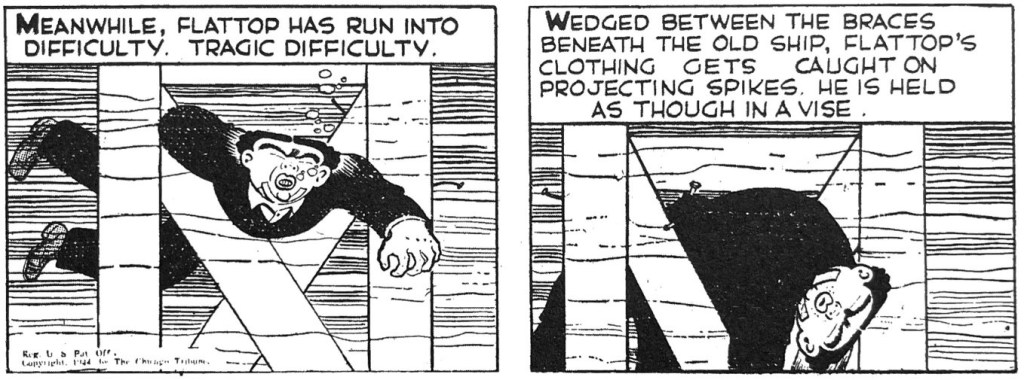

Flattop Gets Spiked – 1944

In 1944, Gould concocted two of his most venal villains. Flattop was simply psychopathic as a hit man, and he would be followed by The Brow, who was sadistic and a spy. Hiding beneath a ship being constructed, Flattop gets hung up on protruding spikes, leading to another close-up of deserving death.

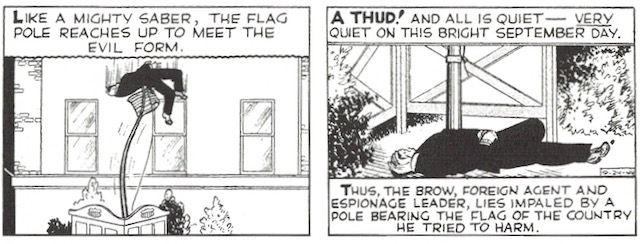

The Brow Is Killed By Patriotism – 1944

Far and away the most inventive and stomach-turning death in the first decades of Dick Tracy was the impaling of The Brow. I covered this in greater detail and with more context elsewhere. But here again is the wartime spy getting impaled on the flagpole commemorating the city’s war dead. The bending flagpole is a gruesomely brilliant touch to amplify that moment of maximal tension that will ultimately pierce the villain.

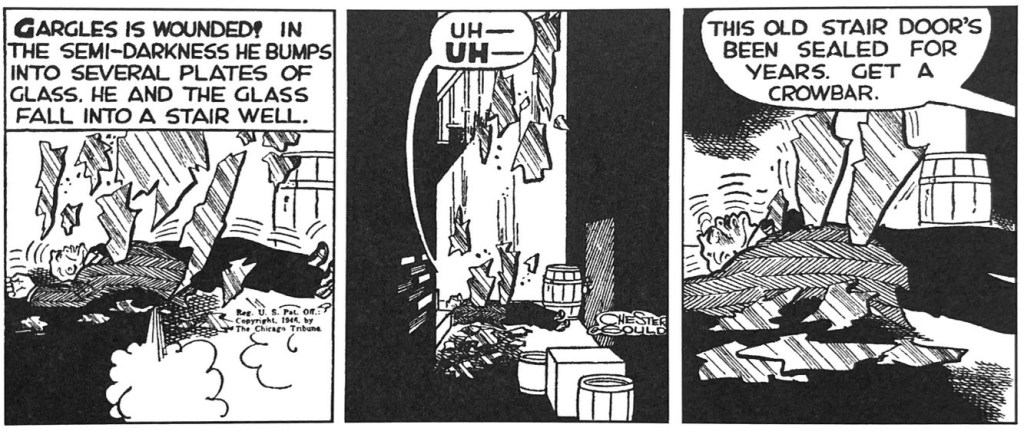

Gargles Eats Glass – 1946

Falling through a skylight, again in comic strip slo-mo, Gargles gets sliced across three panels. And Gould can’t resist giving us his final shudders. In fact Gargles hangs on until the next strip so his final words exonerate an innocent suspect just in time for Christmas. One of the hallmarks of Dick Tracy was the strip’s extremism, Gould’s penchant for balancing unmatched graphic violence and angry vindictiveness with maudlin sentimentality. This sequence leads up to a Christmas strip that celebrates the villain’s death and the joy of the season.

Mumbles’ Cry for ‘Elp’ – 1947

Making a speech impediment somehow expressive of a villain’s evil was a questionable move to begin with. But Gould doubles down on this conceit by having Mumbles frantically, futiley hail for “ELP”.

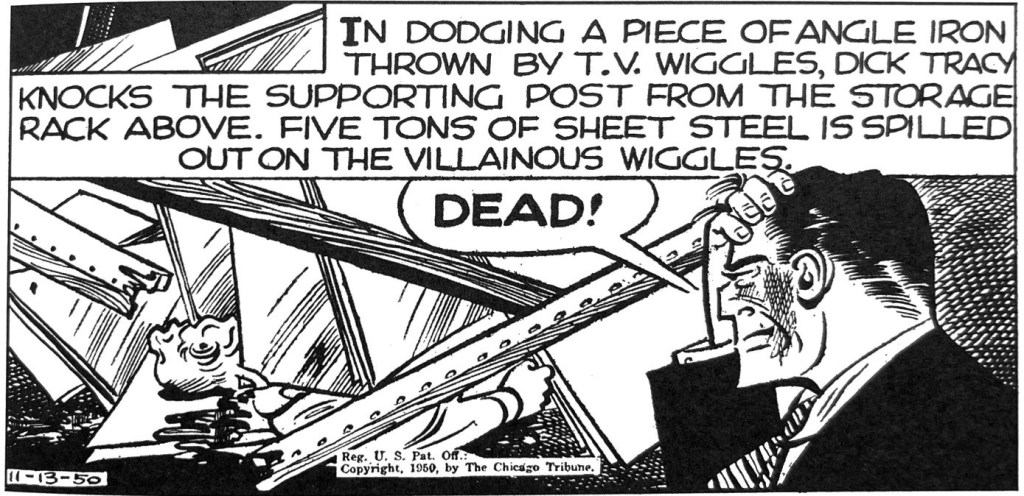

T.V. Wiggles Can’t Move – 1950

Gould loved to draw in that little bit of grisly business to convey violence. While he used a heavy, cartoonish line and unreal, expressionist style that set the strip far apart from the illustrative style of most adventure strips, Gould used other ways of communicating hard-boiled reality. He had a penchant for objects penetrating bodies. Bullets often passed through their targets in shootout sequences. And as the deaths of The Brow and Gargles showed, the impaled body has a special place in Gould’s sense of horror. The death of T.V. Wiggles comes from fallen metal sheets that form an ersatz coffin. But it is that little corner of metal piercing a flap of neck flesh that telegraphs the experience of death itself.

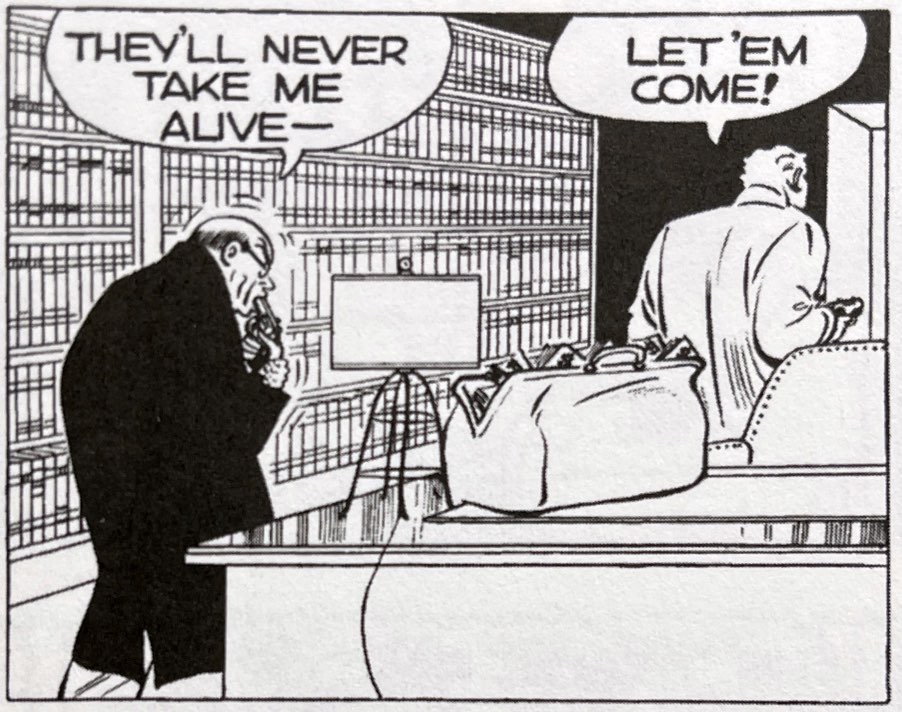

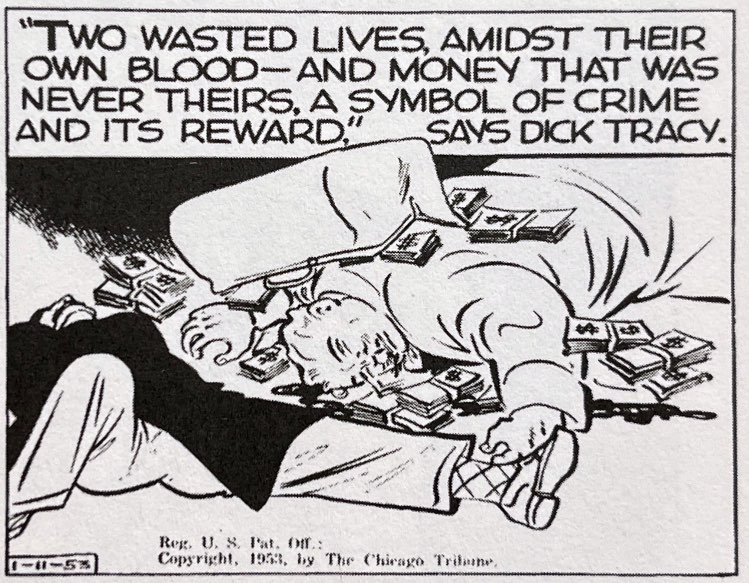

Mr. Crime and Judge Mix Blood and Money – 1953

Mr. Crime was among Tracy’s most ruthless, pitiless villains of the 50s, and in the context of the Gould moral universe I am surprised (and a bit disappointed) that he suffers a simple shootout with Tracy. In fact Gould reserves the grisliest image for Mr. Crime’s extorted dupe, Judge Ruling. When cornered, the corrupt Judge chooses suicide. But of course Gould can’t give us a gunshot sound effect heard through a closed door. We have to get an image of Judge Ruling eating the gun, complete with cheek lines to suggest how deep he has planted the barrel. But we’re not done with this duo. As is his wont, Gould closes in for a final tableaux of both villains swimming in their own blood and money.

Flattop Jr.’s Near Miss – 1956

Flattop Jr. was indeed the son of the original Flattop, but he was framed by Gould as a neglected youth who embodied the overhyped scourge of the 1950s – the juvenile delinquent. He appears to meet his end in a theater fire he himself set to cover his escape. Despite the massive explosion Gould depicts dramatically, and the presumption of having died in the inferno, Jr. turns up later where his genuine death takes place in the middle of another villain’s cycle. And so that final contemplative panel here turns out to be ironic.

Great Moments: A. Mutt Meets Jeff (1908)

One of the longest lasting marriages in comic strip history began on March 27, 1908 when Bud Fisher’s wildly popular A. Mutt comic strip anti-hero meets a character who soon became his companion until the strip finally sputtered to an end in 1983.

As told by Jeffrey Lindenblatt in the NBM reprint of early strips, A.Mutt had a whirlwind start in the five months from its brilliant inception to the introduction of Jeff. Bud Fisher was a self-taught artist who talked his way onto the the San Francisco Chronicle in 1906. He worked his way up from layouts in the art department to spot illustrations around news stories to regular caricatures in the sports section. Here is where Fisher sold editors on an idea for a daily strip that would top the sports section with betting neophyte A. (Augustus) Mutt’s uninformed picks to win one of that day’s horse races. The next day’s strip would include Mutt’s winnings, losings and mood after the real world results.

A.Mutt was an instant hit, but its Chronicle run lasted only 26 days. The strip attracted the attention of no less than notorious newspaper staff raider William Randolph Hearst, whose rival San Francisco Examiner battled the Chronicle for circulation. As he had done so many times in his “Yellow” newspaper war with Joseph Pulitzer in New York a decade before, Hearst drowned Fisher in cash and the promise of national syndication to lure him to the Examiner less than a month after A.Mutt launched. Eventually Fisher would leave Hearst too for a much more lucrative syndication deal that became a model for decades of lavishly paid cartoonists.

Fisher’s final A.Mutt for the Chronicle appeared on Dec. 10, 1907, but that last iteration had one very important (and lucrative) addition – “Copyright 1907 by H.C. Fisher.” In Lindenblatt’s telling, Fisher accompanied the artwork to the printing department that day and before the printing plate was struck added that copyright note that led to his being one of the wealthiest cartoonists of his and subsequent decades. Until his death in 1953, Fisher benefited from gushers of revenue from licensing, theatrical and syndication deals that saw Mutt and Jeff on just about anything willing to pay Fisher royalties. There were a number comic strip millionaires during the golden era of newspaper circ wars, but few were as showy and press savvy about that’s wealth than Fisher.

It is under Hearst’s banner that A.Mutt moved quickly away from racing track picks, added Jeff and because a buddy strip that also introduced extended continuities. Alas, the sad anachronistic later decades of Mutt and Jeff strips obscured its earlier, genuinely witty, edgy slapstick years.

But in its early years the strip was indeed gritty. In fact, Mutt meets Jeff in an asylum, one of many incarcerations for him. This time he meets up with multiple cases of delusional inmates, including a diminutive fellow who fancies himself boxer Jeff Jeffries.

While the strip soon evolved beyond its origin as a sports cartoon, it carried with it to mainstream comics pages the sharp-tongued banter, slang, and snide irreverence that typified much of sport page cartooning. Mutt and Jeff took on politics, lampooned public figures, poked at social pomposity, and even ventured down to Mexico in the 1910s to engage with Pancho Villa.

Mutt was also among the first of a staple for the comics pages – the hapless schemer. Always looking for a buck, failing at the serial jobs he tries, the early Mutt conspires with Jeff (who is usually more flush) just to score a much-needed meal. Well evolved from the early simpletons of comics like F.O. Opper’s Happy Hooligan’ and Ed Carey’s Simon Simple, Mutt was like Harriman’s Baron Bean and Goldberg’s Boob, the American always on the make but falling short, working the angles unsuccessfully at the margins of America’s booming modern economy. The rising middle classes at whom 20th Century newspapers generally were aimed seemed to delight in the misfired ambitions of characters like Baron and Mutt, later Moon Mullins, Bobo Baxter and to some degree Andy Gump. It is a figure that extends into Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, Chester Riley and Ralph Kramden. Failed ambition is often leavened ironically with empty bravado and inflated self-confidence. It is light satire of America’s core tropes: social and economic ambition, masculinity, mobility, looking for the main chance.

The candor of Mutt and Jeff is in full display in 1918 when the duo scheme to dodge the draft.