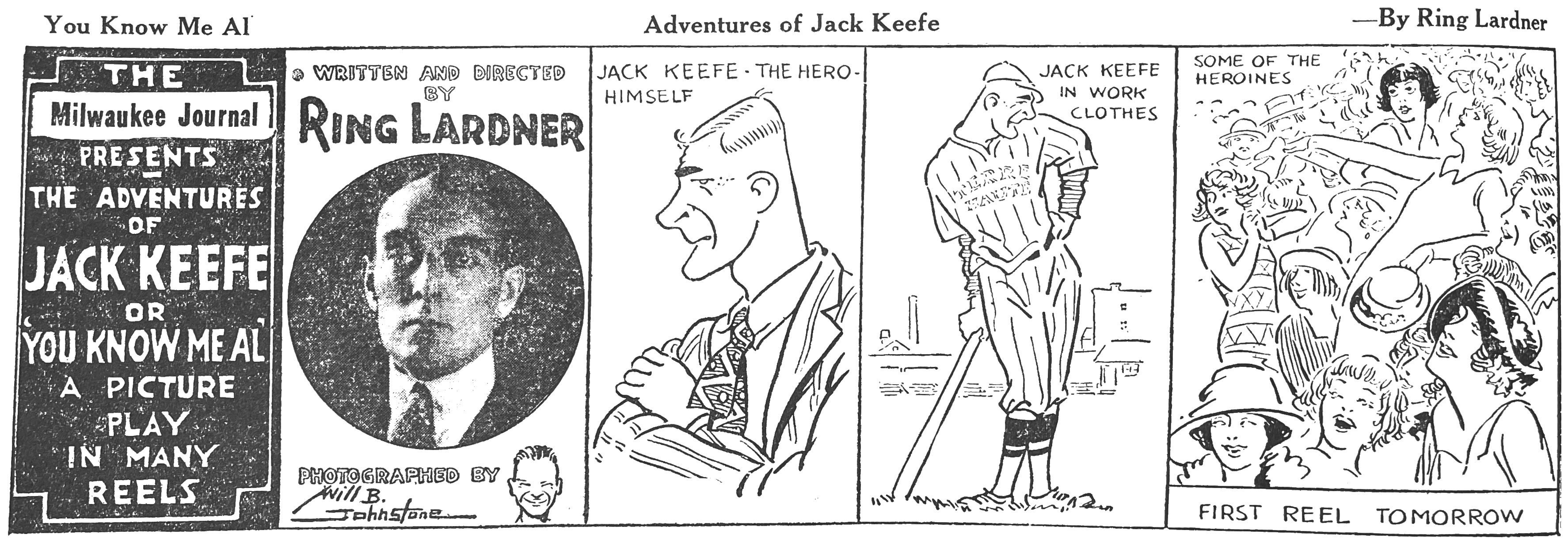

The 1969 moonwalk sparked both a wider interest and new respect for the science-fiction genre and tons of reflection on the ways speculative fiction anticipated contemporary tech. References to our realizing a “Buck Rogers” future flooded the media zone, and Chelsea House published in late ’69 one of the earliest oversized reprints of classic comics, The Collected Works of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, introduced by Ray Bradbury writing about “Buck Rogers in Apollo Year 1.”

I was age 11 at the time, and had my own fleeting dalliance with sci-fi that drew me to this Chelsea volume at the local library and helped start a much deeper, longer love affair with newspaper comic strips. But an unusual source of comics fandom came into my house at the same time – a trade advertisement for high quality paper stock from the Warren Paper company. Some background. My father was a commercial artist with his own small ad agency in Northern New Jersey. We received at the home office a ton of trade magazines and ads. The S.D. Warren Paper Company promotions were far and away the smartest, most alluring trade marketing I have seen, then or since. To demo the print effect of their premium paper stocks, they created these lush, deeply researched pieces of content marketing that dug into topics like magic or the history of the circus, etc. I recently came upon the one Warren promote that remains etched in my memory – the 1970 celebration of how the Buck Rogers strip imagined accurately the gadgetry and transformative technology of the future.

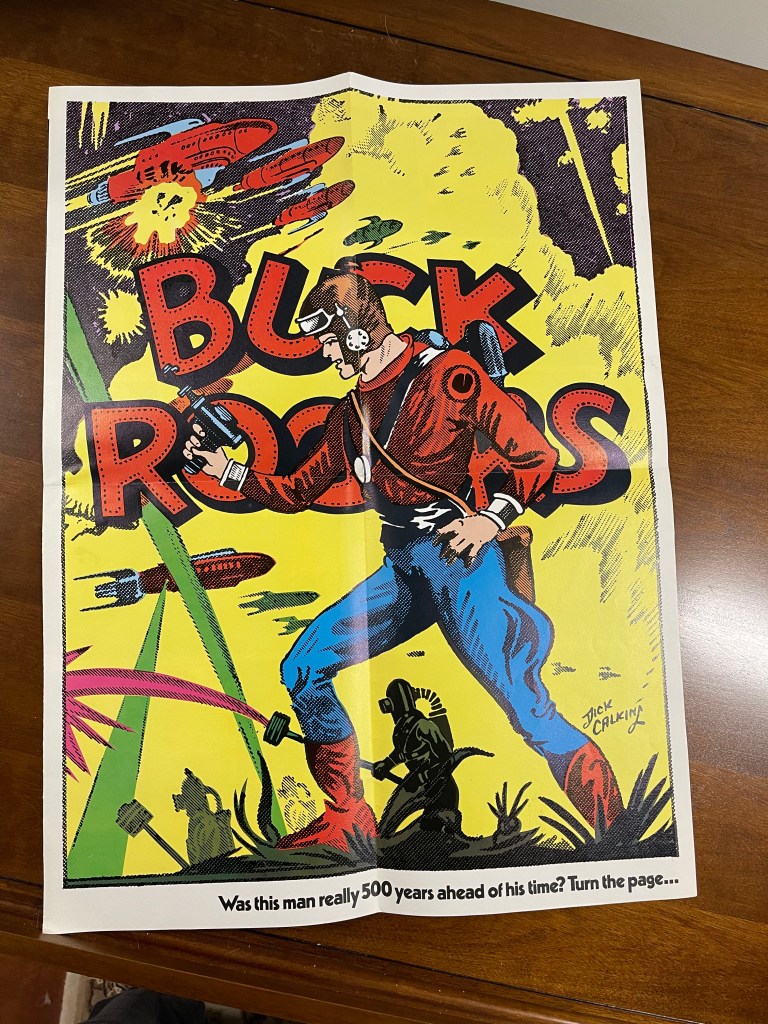

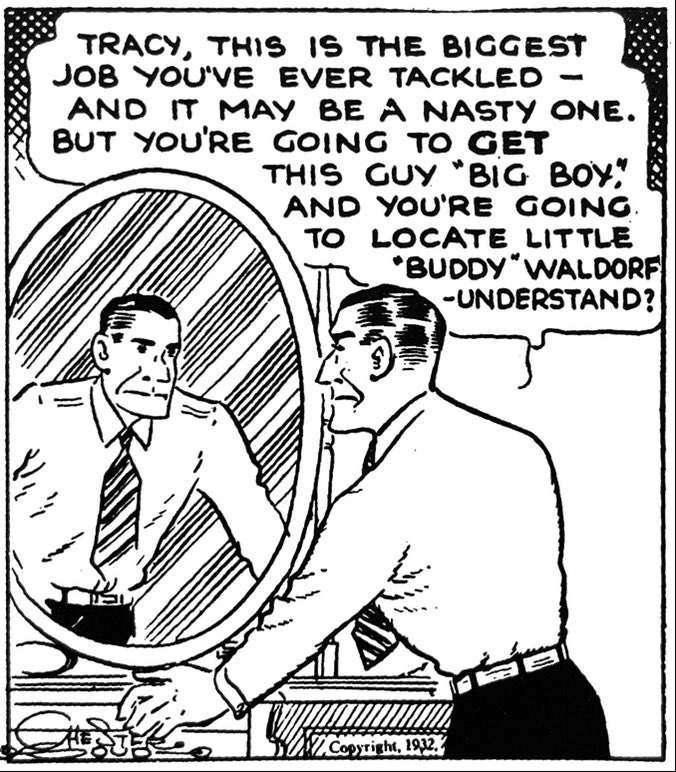

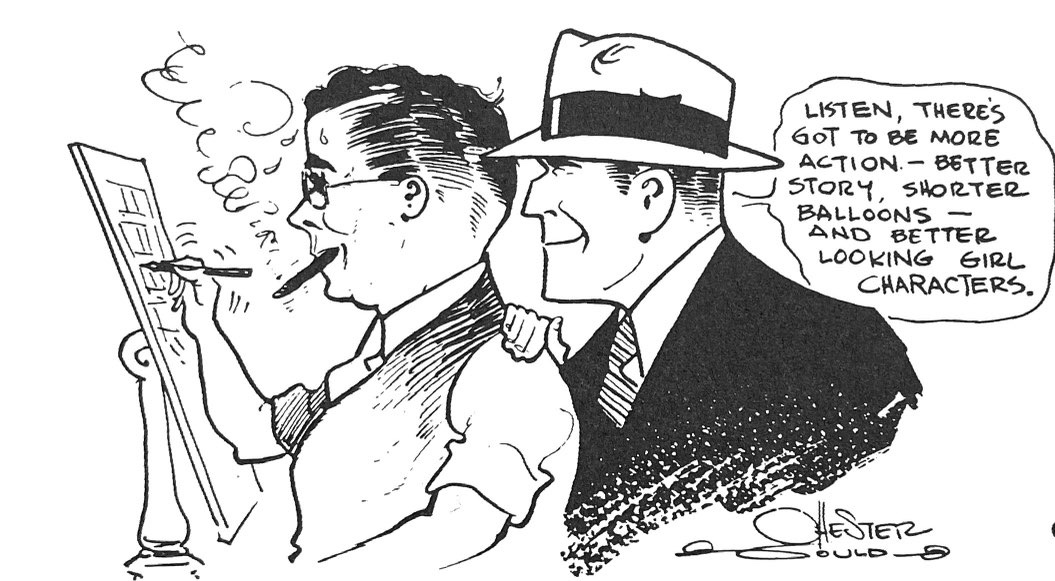

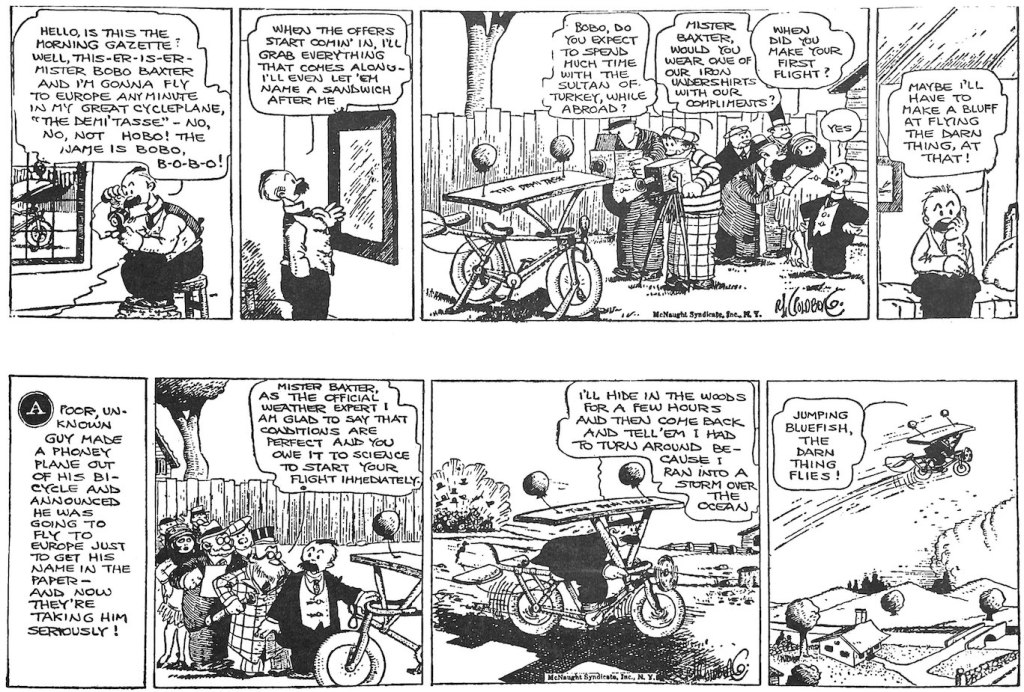

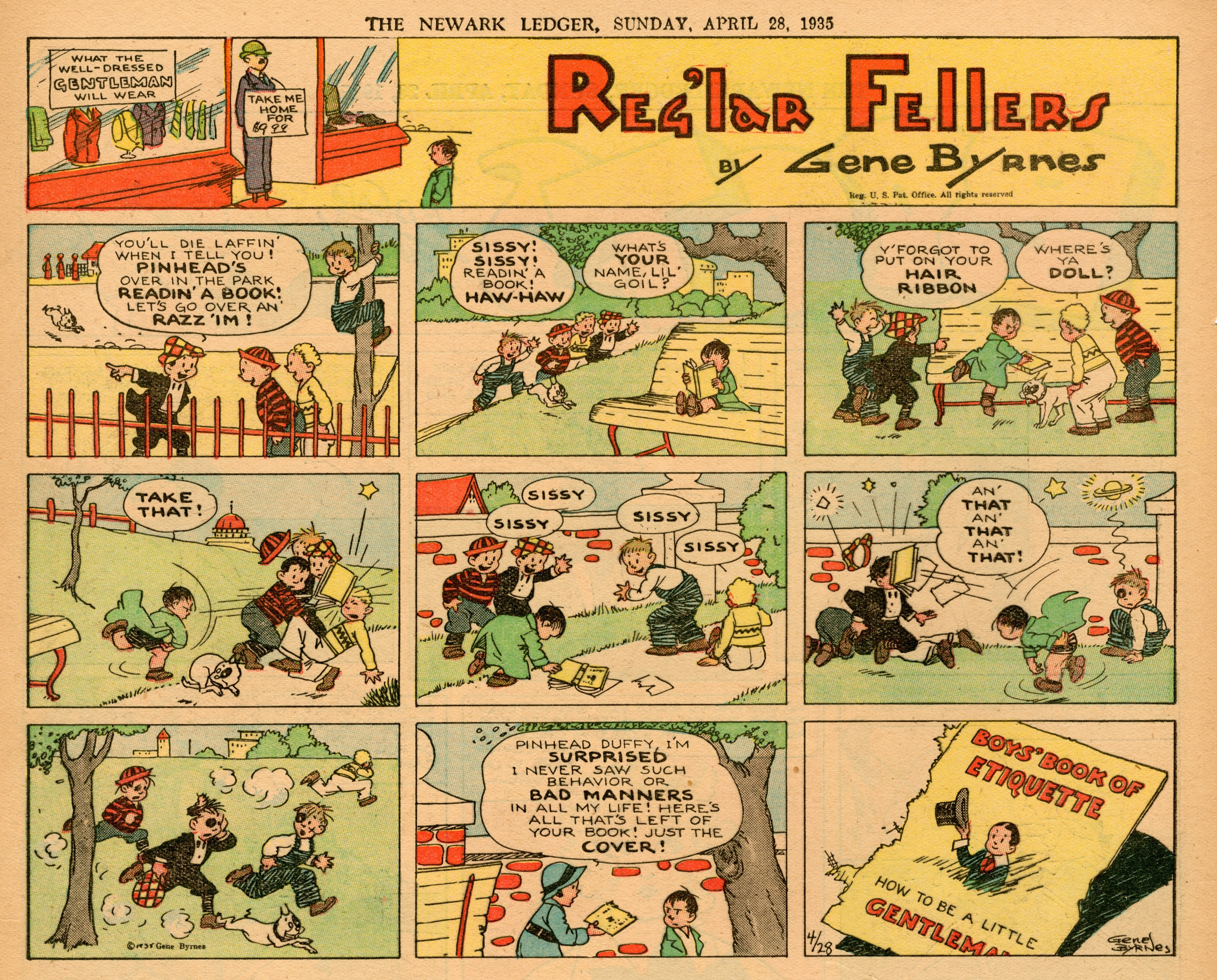

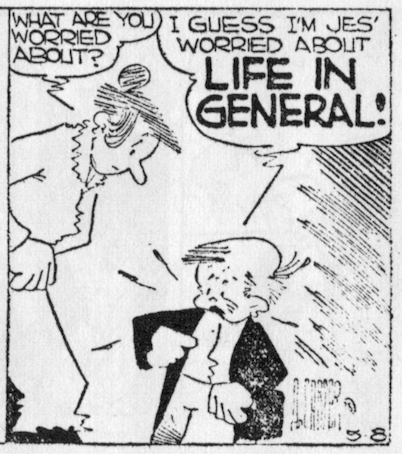

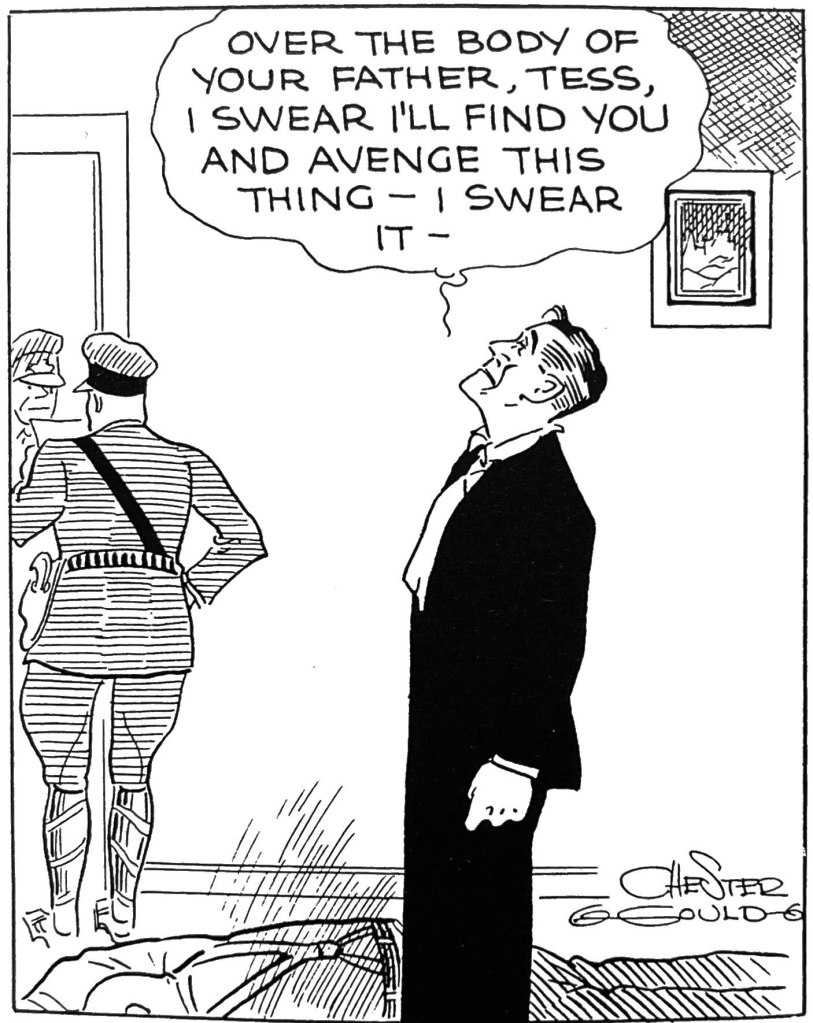

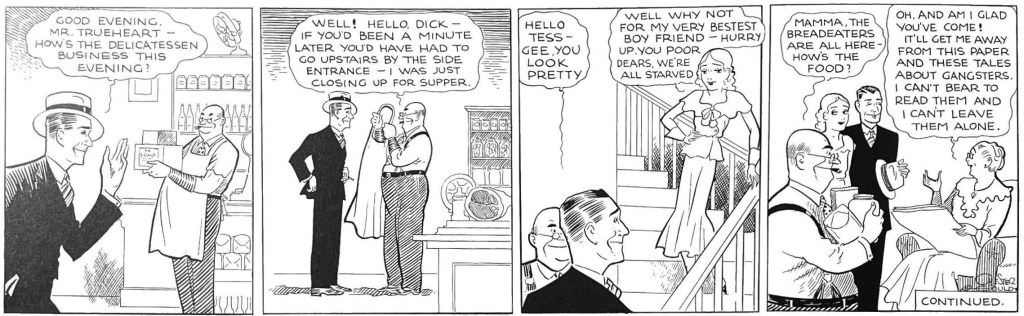

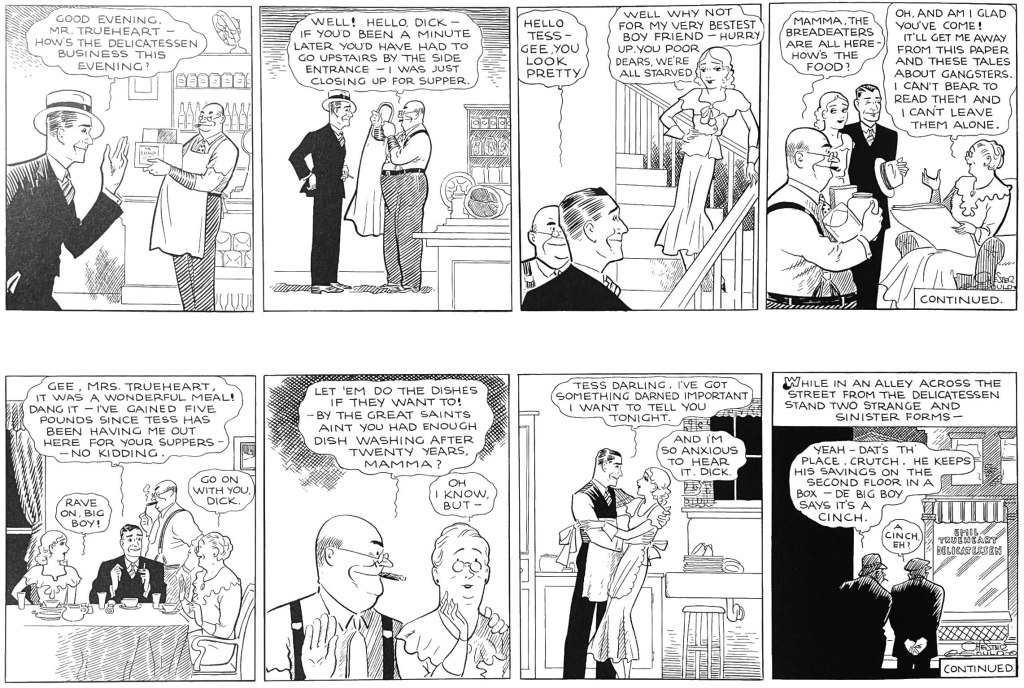

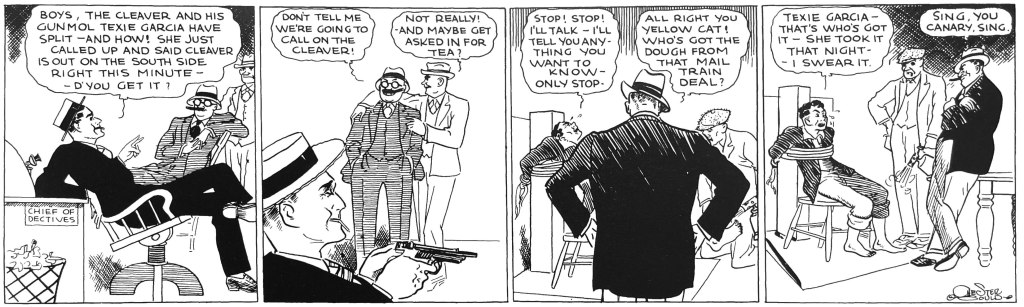

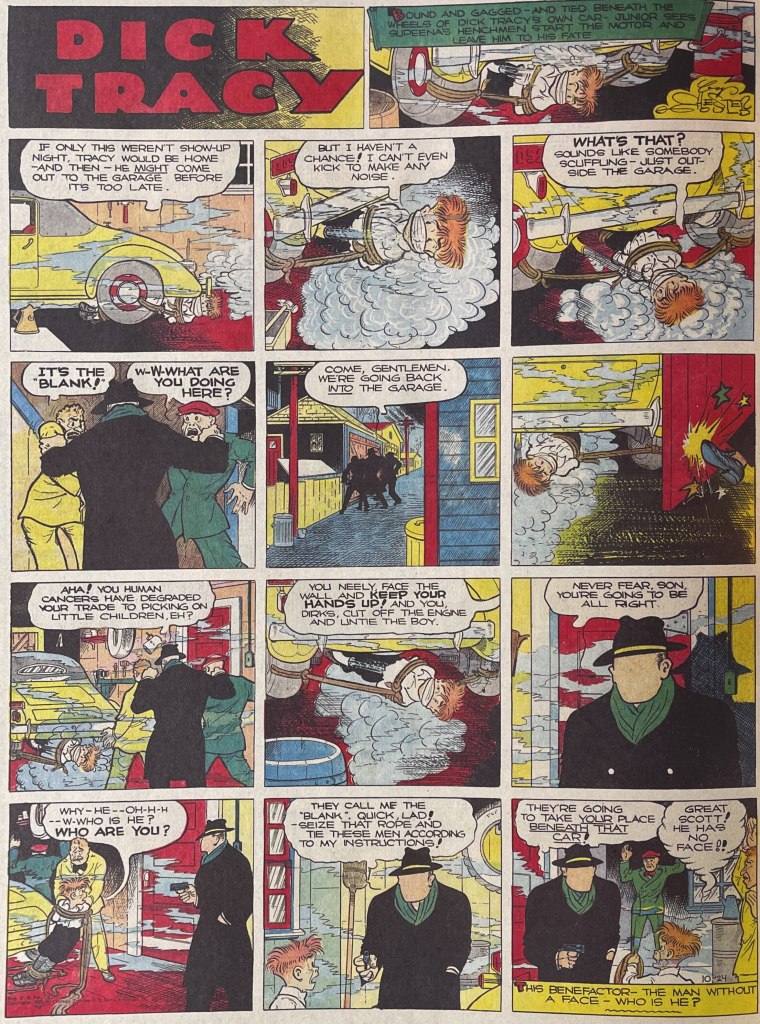

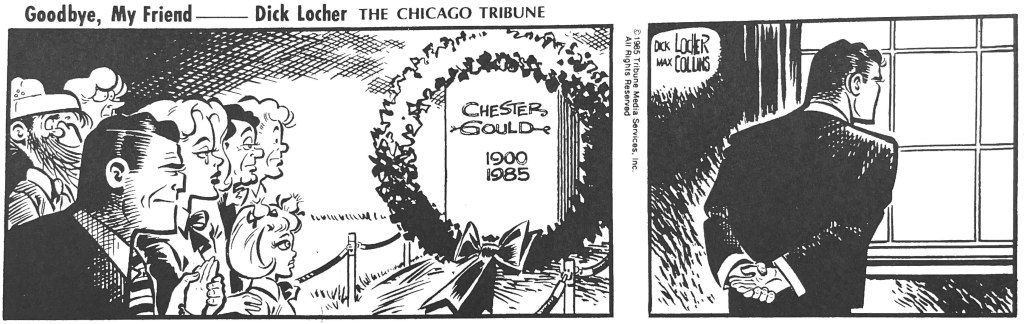

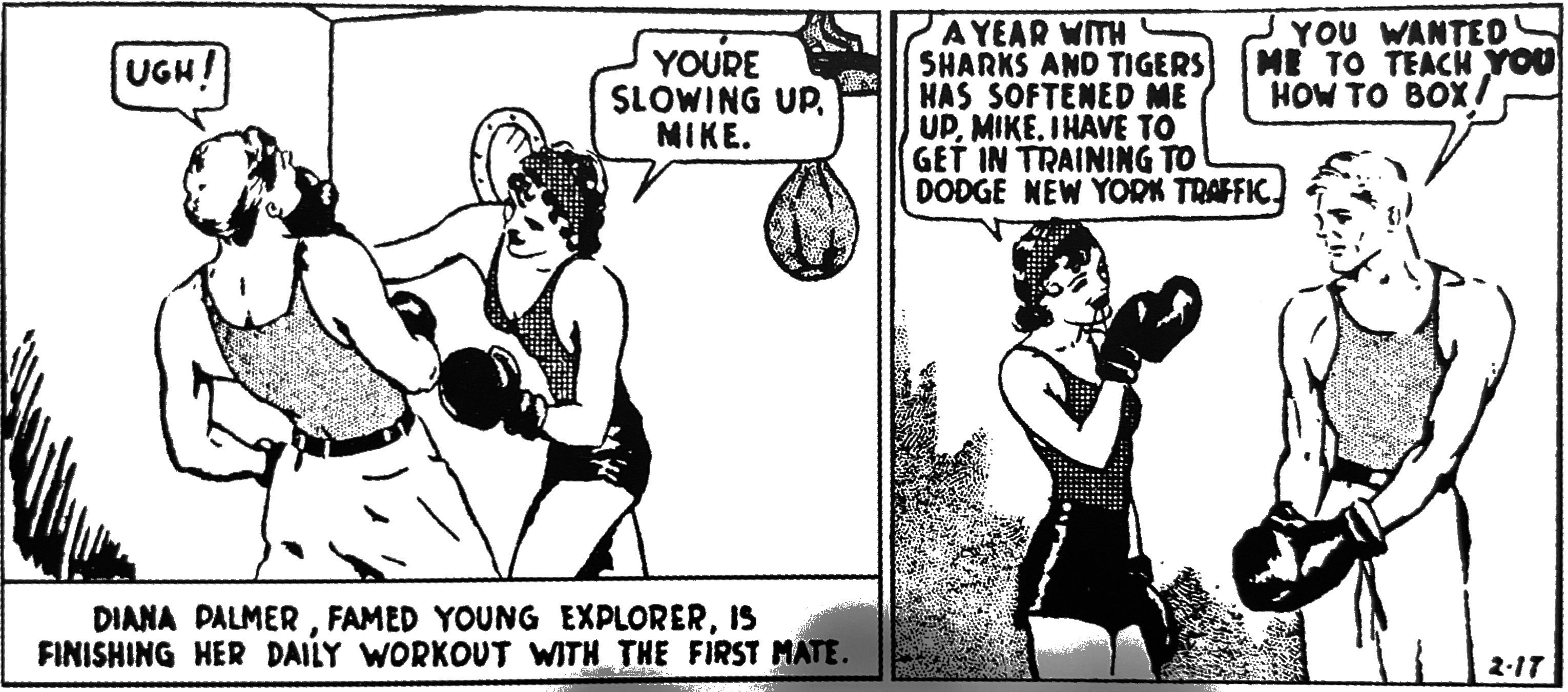

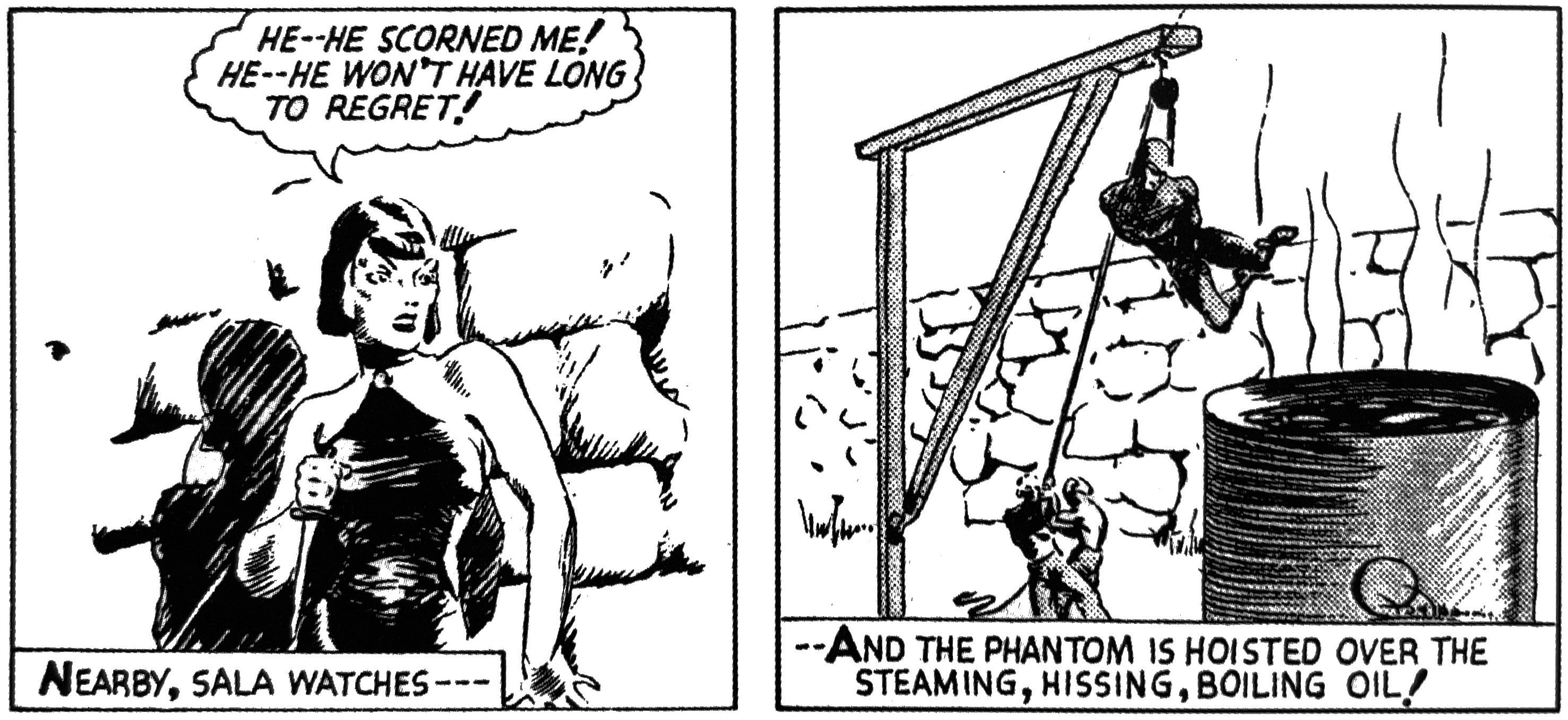

The one-piece fold-out opened first onto that gorgeous splash above, with the classic Dick Calkins portrait of Buck in mid battle. These are the kinds of magnified newspaper comics images that helped the 12-year-old me into a love of the form. The line art of Calkns, Chester Gould, Will Eisner are among the first classic artists to captivate me. The art style of Buck Rogers felt at once primitive and technical. Calkins did not have a strong of perspective or even anatomy. Most of his figure positions look stiff rather than dynamic. And yet he brought to ray guns and flying ships a dreamy precision that made them live, perhaps even more than his humans.

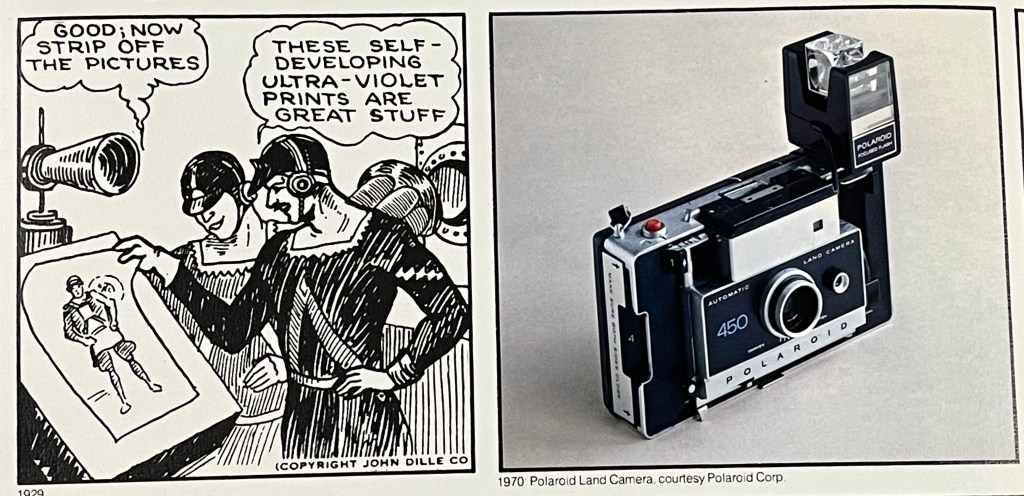

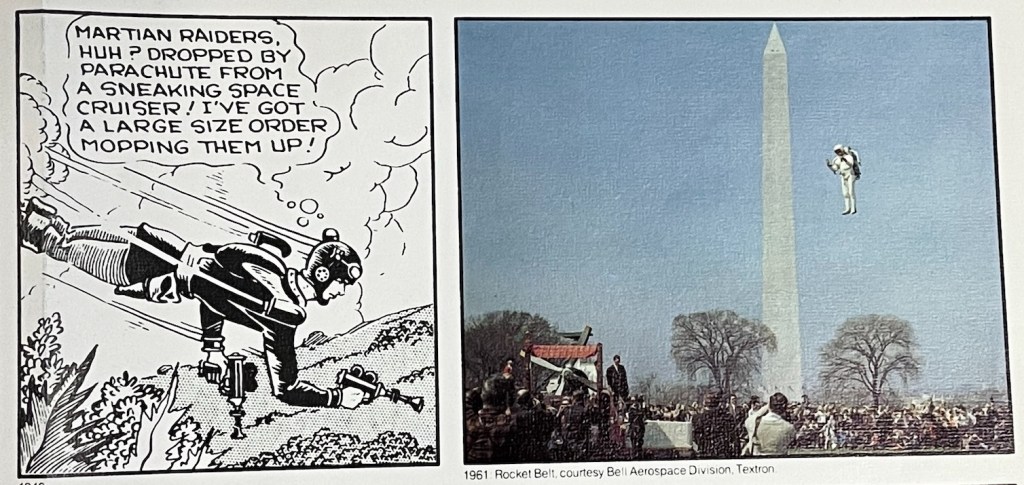

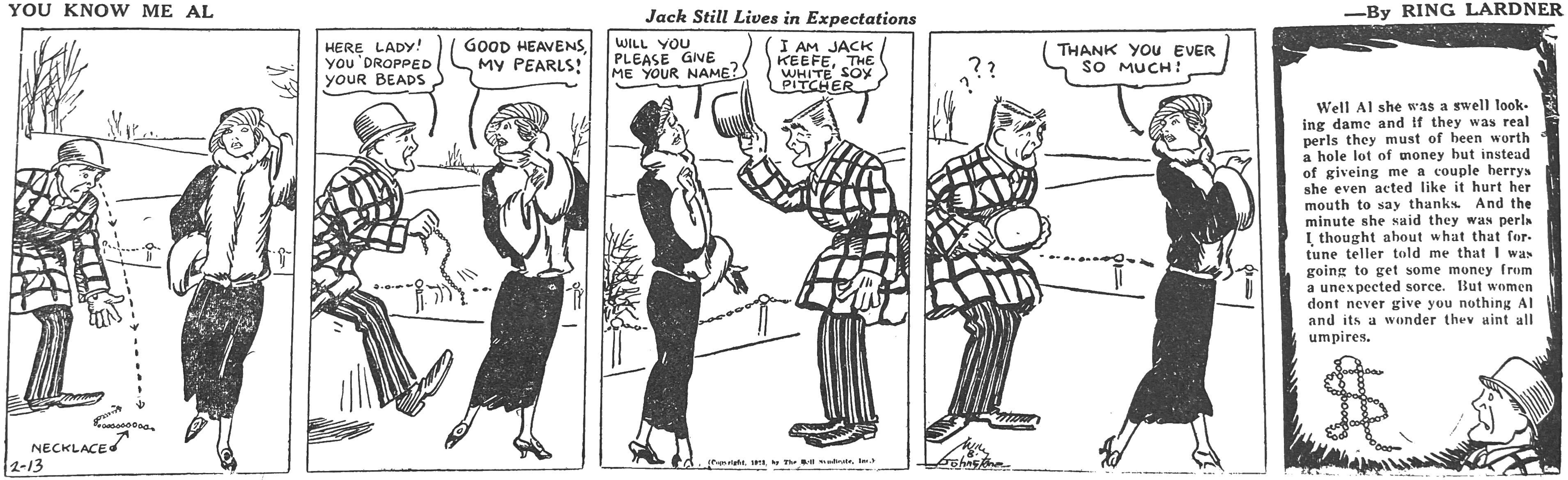

The Warren promo folds out above to a panorama of comparing old Rogers panels to modern innovations like instant cameras, jet packs, surveillance satellites, monorails and more.

This wonderful look back to how the past imagined its future was all in the service of showing off S.D. Warren’s “Lustro Offset Enamel” paper stock, a product name that itself sounded a bit like a cartoon invention. Still, you can’t argue with a content marketing campaign so well done that an 11-year-old remembers it fondly 50 years later.