Nearly 25 years ago IDW’s Library of American Comics began reprinting the full run of Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, starting with the strip’s premiere in late 1931. This week, with the release of Volume 29, the series reached its end, marking Gould’s retirement in 1977. I had been planning to mark this occasion by posting the very first 1931 strips alongside the very last 1977 strips to illustrate the evolution of Gould’s style as well as the decade’s long consistency of his vision. Little did I know that Gould himself would beat me to it. See below.

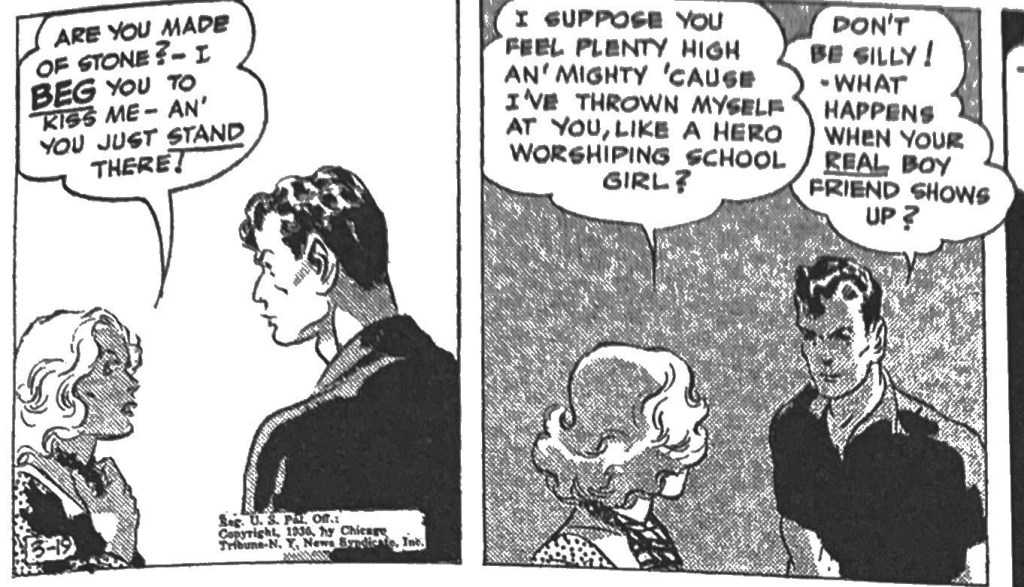

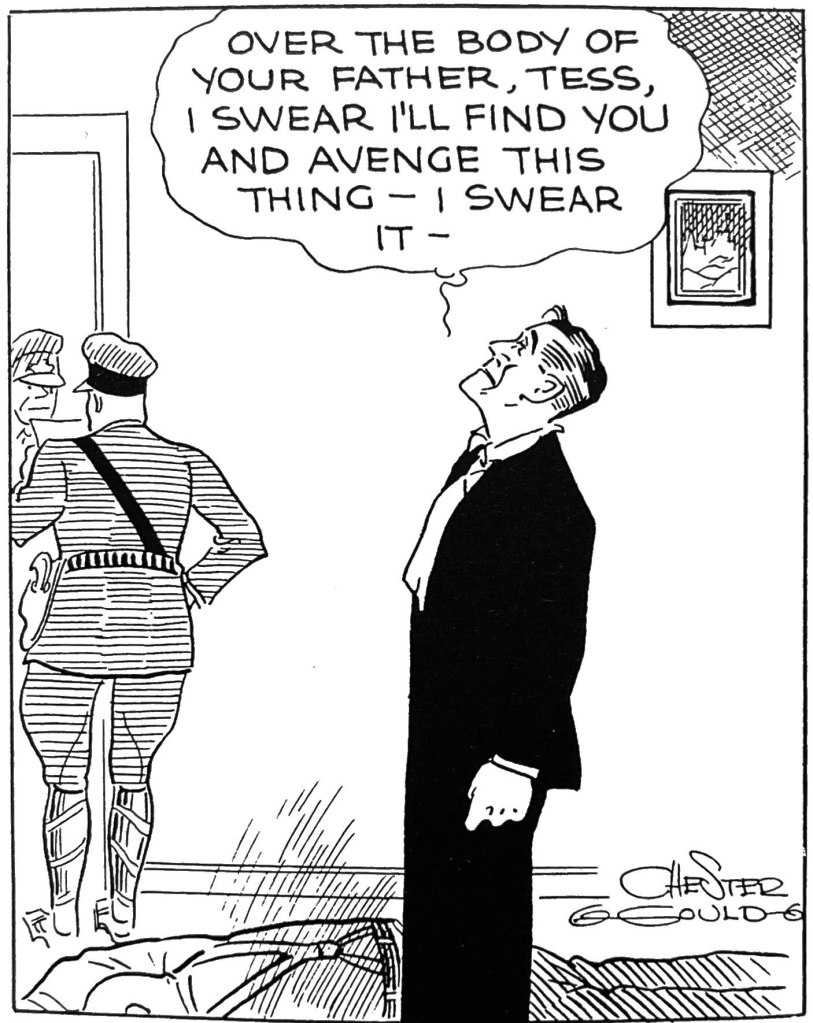

The first week or so of Tracy locates the origin of Dick’s moral commitment to fighting gangsters in the robbery/murder of Emil Trueheart, father of his new fiancé Tess. Tracy was not a cop by trade, but a young man still finding his way. In the sort of surrealistic moment that would typify Gould’s storytelling and visual style for the next 4 decades, Tracy not only finds his moral mission but becomes a “plainclothes” detective as well as a natural leader for the force within weeks of the strip’s launch. The moment of moral truth is captured in the featured panel at the top of this post.

Between 1931 and 1977 Gould’s style had gove through several evolutionary stages. By 1977, Gould’s ink lines had grown thicker and a bit rounder. His more extensive use of close-ups and medium frames were a begrudging accommodation to the shrinking space allotted to strip artists even by the late 1970s.

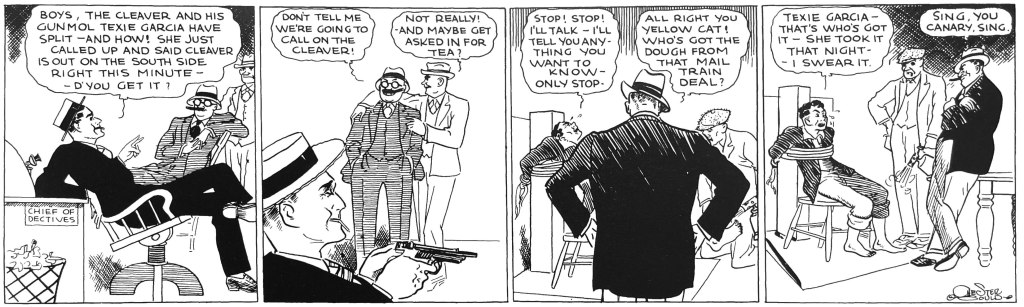

Gould invented his hero as “Plainclothes Tracy” in a series of spec strips he sent to legendary publisher Joseph Patterson, who was in the process of building the New York Daily News into a pioneer of tabloid newspapers. Patterson suggested the change of name to the simpler “Dick Tracy” and seemed to understand that Gould’s penchant for violence, grotesque villainy and even sadism mapped well against his vision of the tabloid style. The gorgeously colored Tracy Sunday strip would be the cover wrapper for the Sunday Daily News for decades.

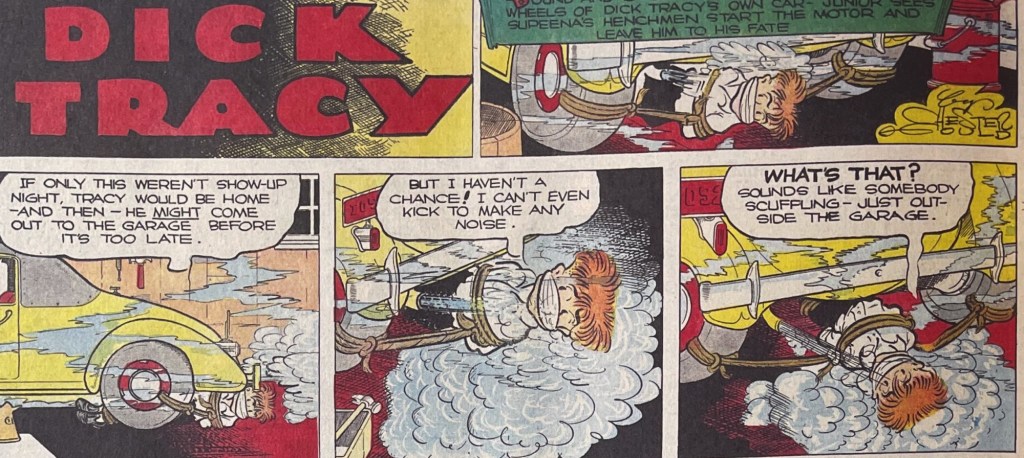

Famous for the brutality of his cartoon vision of crime and punishment, it is revealing that the first panel of the Plainclothes Tracy spec strip is a scene of bondage and torture among thugs.

By the mid 1930s, his signature thick outlines, highly abstracted iconography, extensive use of fields of blacks, and series of bizarre villains were all fully established. The Sunday page below is from 1937 and The Blank adventure.

Dick Tracy holds a special place in my own journey into comic strips. The lush reprint of classic adventures, The Celebrated Cases of Dick Tracy by Bonanza Books in 1970 was one of a trio of reprints that captivated me with the form. It was around that time that I first got hold of Jules Feiffer’s The Great Comic Book Heroes and a Chelsea House oversized reprint of early Buck Rogers strips.

But it was Gould’s starkness in style and story, the extremity of art and character, that pulled me in then and still does decades later. I can think of no other comic strip artist that had such a singular vision. There has always been a peculiar geometry to Gould’s art. His panels alternated between use of deep perspective and no perspective, a weird penchant for flatness and depth. The stances of his characters, especially Tracy and his long inky black columnar legs, was so eccentric and physically improbable. Even though Gould became famous for his love of procedural detail in detection, gadgetry and eventually sci-fi crime-fighting inventions (i.e. the two-way wrist radio), his visual language was minimalist and abstract. His daily strip truly popped from the page of his fellow and able artists because it felt like being dropped into an expressionist daydream.

Gould was as famous for the brutal simplicity of his moral vision as he was for the violence of the action in his strips. The villains were not only surreal grotesques, but they met their end in grisly ways that suggested nature (or God) itself was meting final judgment. The impaling of wartime spy The Brow on an American war memorial flagpole is the best known. But Gould followed a formula with every adventure that moved towards a protracted manhunt and chase of the villain, which usually ended with the rogue’s end often via some strange knot of fate and chance.

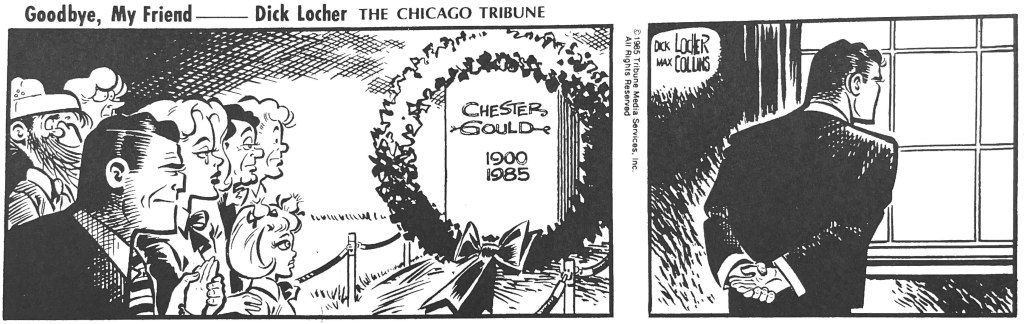

Gould himself met a more peaceful end in 1985. The strip’s writer Max Collins and artist (ands former Gould assistant) Dick Locher memorialized him in the same simple, declarative style for which the master himself was known for decades.