Harry Hershfield’s Dauntless Durham of the U.S.A. only ran for about a year in 1913-14, but it was among the most fully bonkers American comic strips in its imaginative extravagance. Durham was among several sends of the familiar 19th century hero/damsel/villain melodrama. Our damsel is kidnapped relentlessly by the mustachioed, top-hatted Desperate Desmond and rescued in improbable ways from impossible peril.

It is hard to convey the weirdness of the situations and solutions Hershfield concocts. In one episode, Desmond caries damsel Katrina to the top of the Statue of Liberty, planning to “cremate” her on the torch. A puff of Desmond’s cigarette smoke coming through the Statue’s arm reveals his presence to the pursuing Durham, and the chase is on. In another, Desmond tries to distract Durham by tossing a toy dog onto the third rail of the New York subway, expecting him to rescue the pooch. It just gets weirder.

Bill Blackbeard argues in his intro to the 1977 Hyperion Press reprint that Dauntless Durham followed on C.W. Kahles’ Hairbreath Harry, originated by H.A. MacGill in the NY Journal in 1904. And Blackbeard contends that these and other lampoons of the hero melodrama were picking at a long-obsolete form. American popular culture had long ago moved beyond these simple adventures, but satires of the form persisted in the comic pages. This is not entirely accurate. The theatrical scenarios of this type (dubbed the 10-20-30 melodramas after the 10-20-30-cent ticket pricing) were extinct by about 1910. But the format of villainous villains, improbable peril and preposterous rescues were taken up by early film. In fact, as Ben Singer outlines in his

Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts (2001), the early 1910s saw the genre peak in famous cliffhanger serials like “The Perils of Pauline.” These highly sensational and wildly unreal stories were familiar and contemporary to most audiences. But Hirshfield’s send-up of the genre is noteworthy because it demonstrates how the comic strip medium was positioning itself in relation to other mass media forms. Its deeply ironic perspective, its eagerness to poke at every social type, every form of popular entertainment, every politician, every institution, was unlike the earnestness of other media: film, literature, painting, music, theater.

And Hershfield enjoyed the lampoon format. Like many early cartoonists, he was a sports illustrator who moved to strips. He preceded Durham with a villain-focused Desperate Desmond strip. Desmond battles the heroic Claude Eclair in that series, where Hershfield honed his skills at crafting outlandish perils and rescues. Desmond reappears in Dauntless Durham several months into the series and remains the foil throughout.

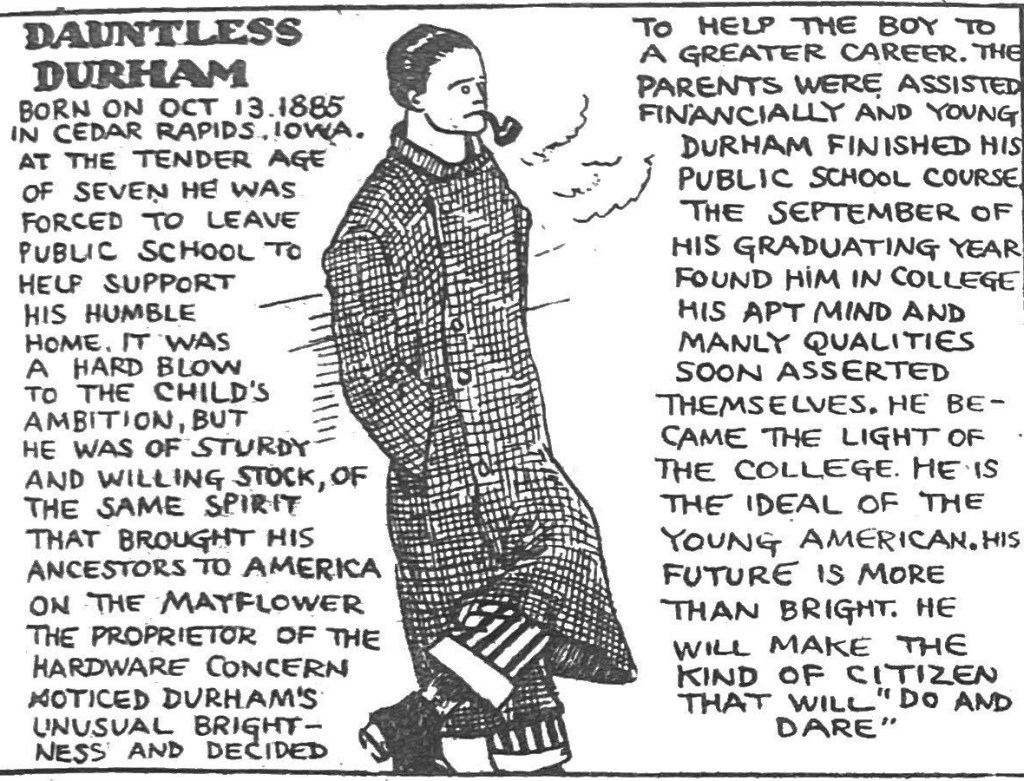

But in this strip, the focus is on the hero and the chase. Durham is right out of dime novel heroism. He is described in the opening strip as a youthful fraternity brother who is privileged by merit, not just blood. He is ascribed Mayflower lineage but more importantly a rags to riches backstory. Following the classic Horatio Alger mythology of American success, Durham brings his family and himself out of poverty through hard work and the generosity of a rich benefactor – “pluck and luck” as Alger described it in his stories of the late 19th Century. “He is the ideal of the young American. His future is more than bright. He will make the kind of citizen that will ‘do and dare.’” “Do and Dare” was in fact the title of a late Alger novel and denotes an American spirit of action and risk-taking.

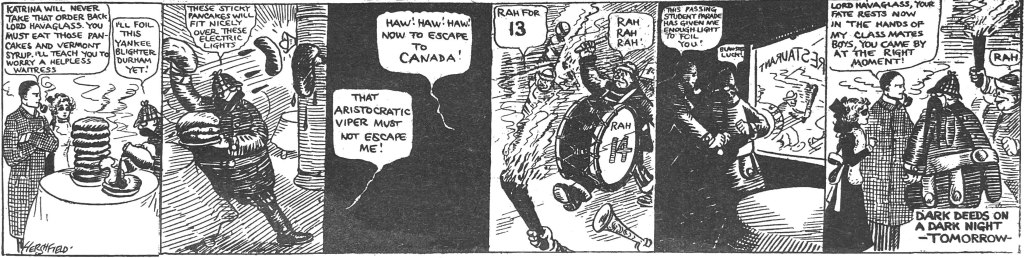

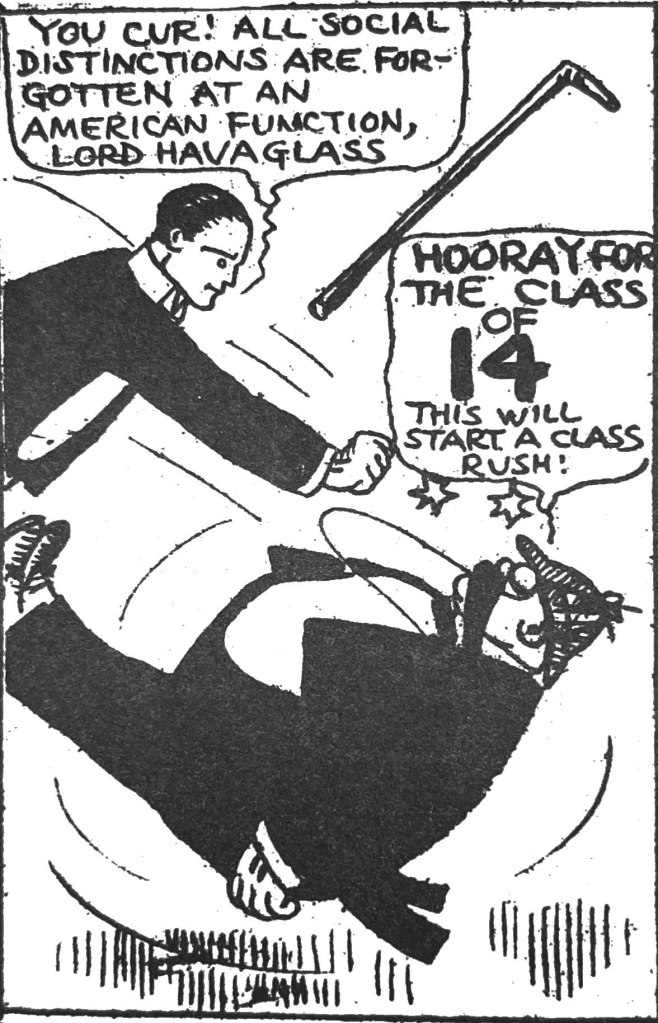

If Dauntless Durham takes an ironic stance towards other pop culture, the strip is baldly nativist in the ways Hershfield draws as American character strengths. Many of the early Durhams are preoccupied with egalitarianism. The first villain is Lord Havaglass, a monocled, obese aristocrat and defender of British classism. The early strips frequently distinguish Durham and America’s disdain from Old World privilege and class division. Hershfield meant to underscore the “of the U.S.A.” of the strip’s full title.

And the early strips are steeped in politics. The heroes attend Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Durham ventures to Mexico and battles Zapata. He brings damsel in distress Katrina to Ellis Island to show off American openness to emigrees. The strip demonstrates the ways that popular creations like Durham reconcile tensions in American culture. On the one hand, Durham’s own Mayflower lineage reinforces WASP hegemony. Many American leaders were at best ambivalent about the massive waves of immigrants pouring into the US at the time. The industrial engine depended on their labor, and their success validated certain American ideals of being an open, democratic society that rewarded merit over lineage. But at the same time, the WASP scions responded with evermore discussion of bloodlines and breeding, maintaining white hegemony as emigres began flexing political power. Durham is the kind of popular hero who splits the difference and holds the two myths in tension. While a Mayflower descendent, her is not a product of idle wealth but a scrappy striver.

.Along with Hairbreath Harry, Dauntless Desmond of the U.S.A. introduced the rhythms of continuity adventure strips to the form. Serialized adventure and long story arcs wouldn’t flourish until the 20s and especially 30s, but here we see them germinating.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.