A.B. Frost’s 1884 graphic album Stuff and Nonsense was one of the earliest book-length cartoon collection published in the U.S., and it proved to be a milestone in the evolution of the art. Jim Woodring argues that until this point, most American caricature tended to deal in lifeless, static stereotypes. “This collection laid the foundation of real American cartooning: frisky pen drawings of people and animals that exuded rough, warm, egalitarian humor,” he writes in the recent collection of T.S. Sullivant drawings. Woodring credits Frost with bringing character to American cartooning by using facial expression, movement, gesture and more to individuate what had been stiff social types in most drawing of the day.

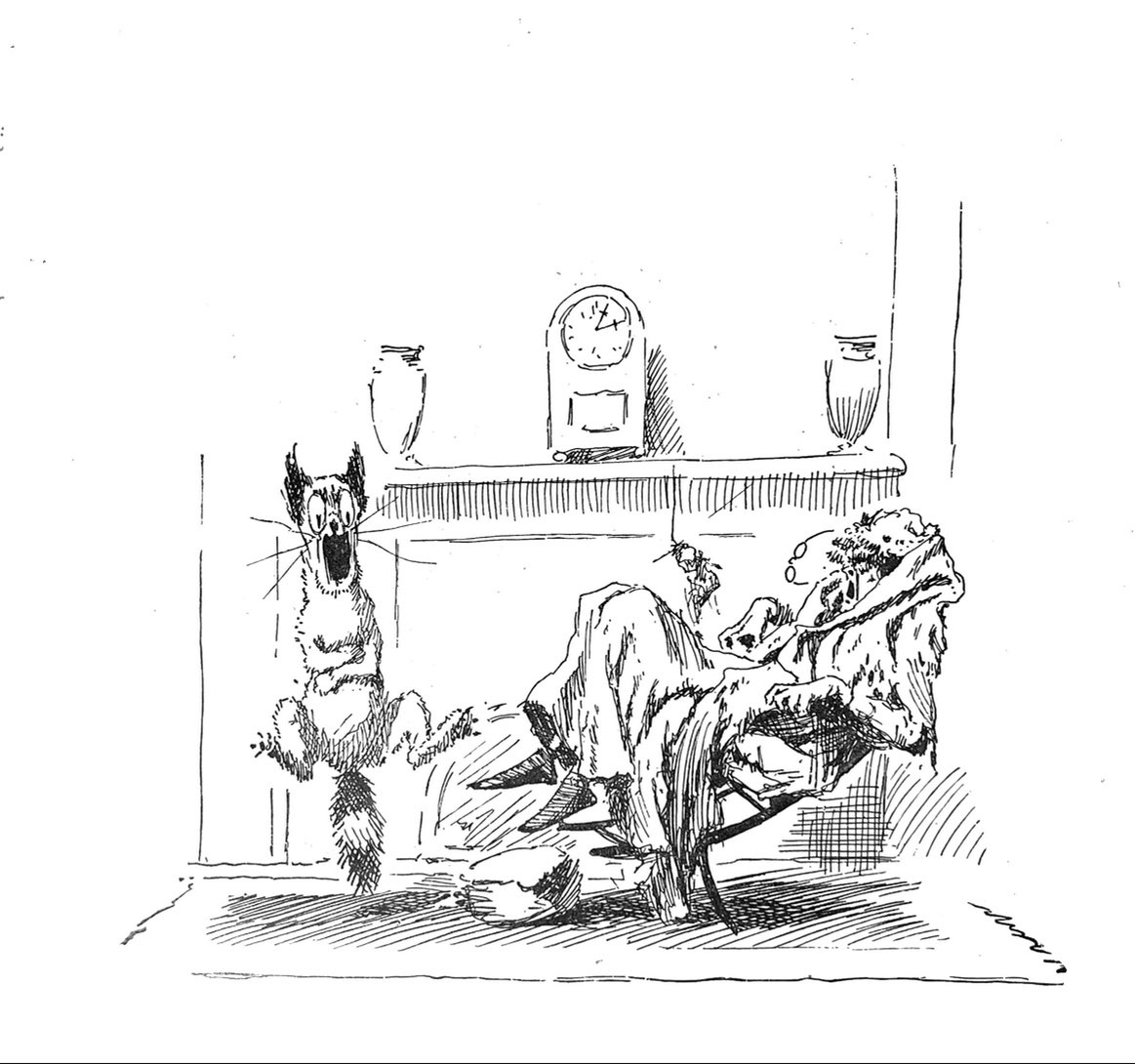

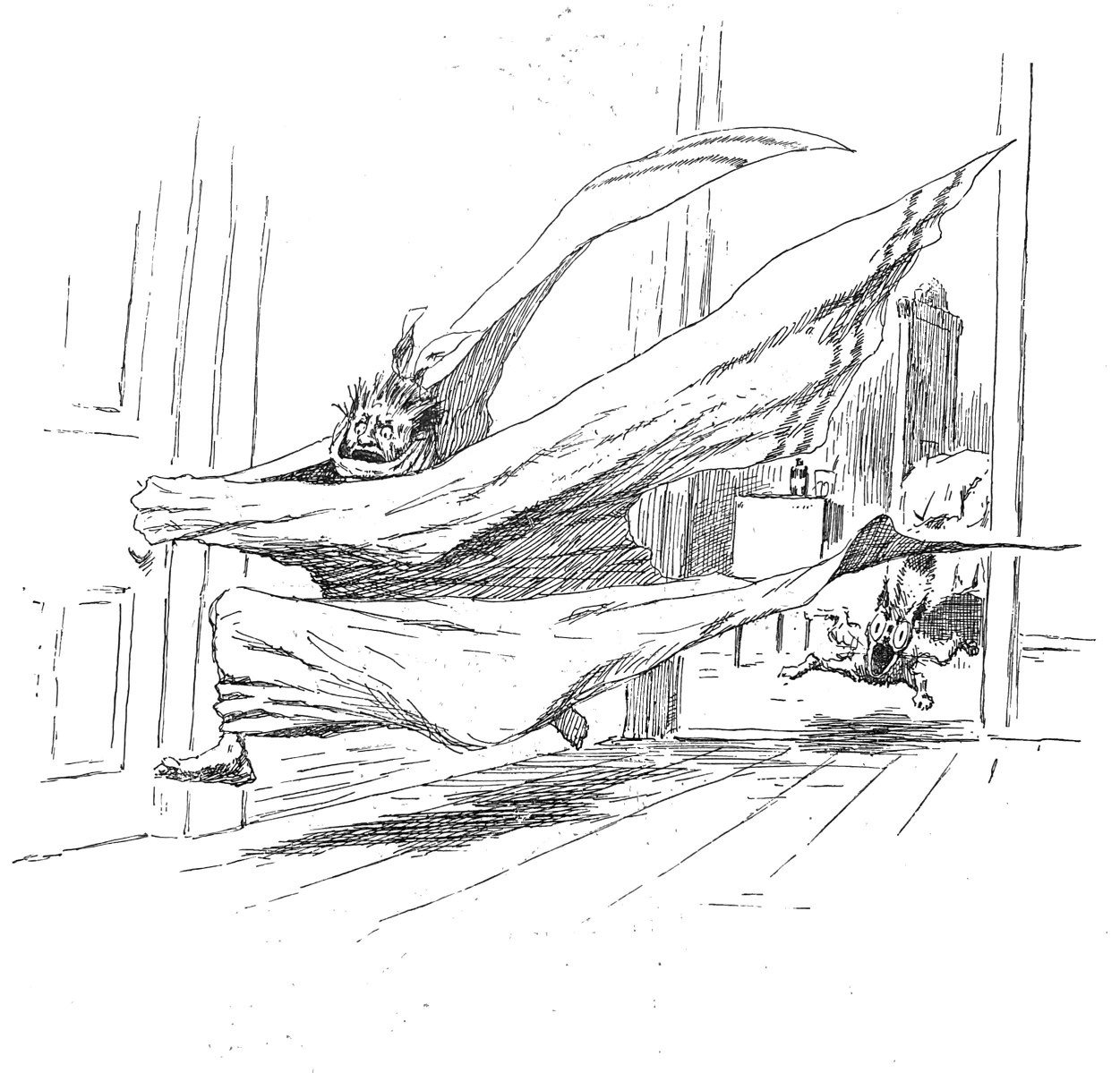

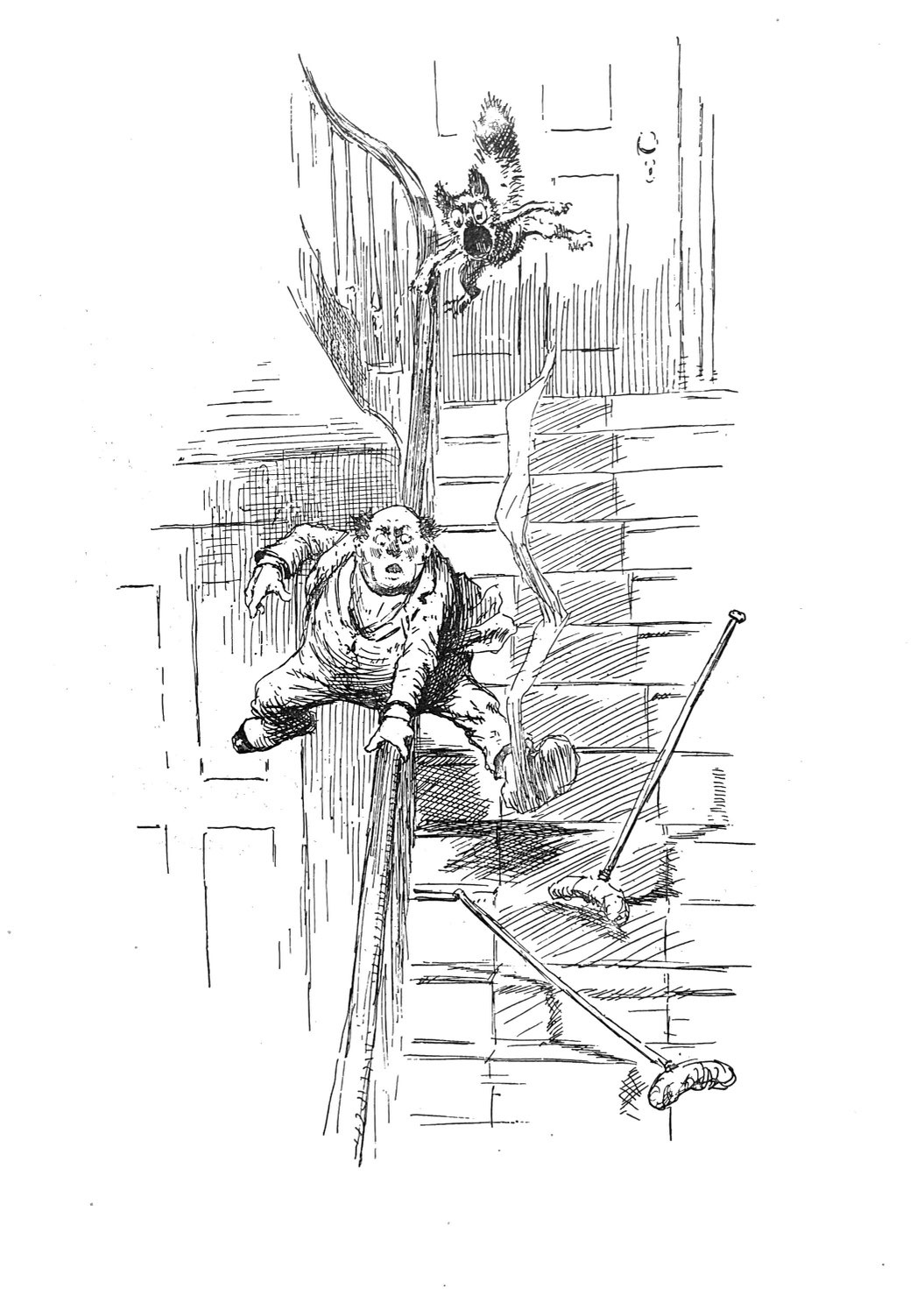

Scanned here from the original Stuff and Nonsense is the first lengthy narrative in the 92-page collection, “The Fatal Mistake: A Tale of a Cat.” Each image is its own full page. The captions I have attached to each are A.B. Frost’s own, although in the original book they are found in the Table of Contents rather than beneath each image.

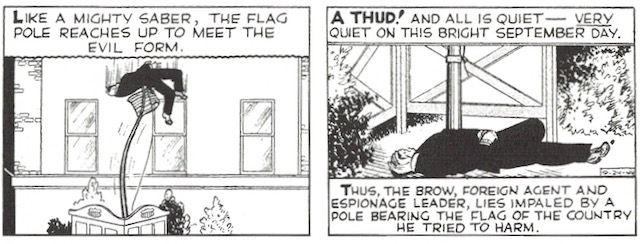

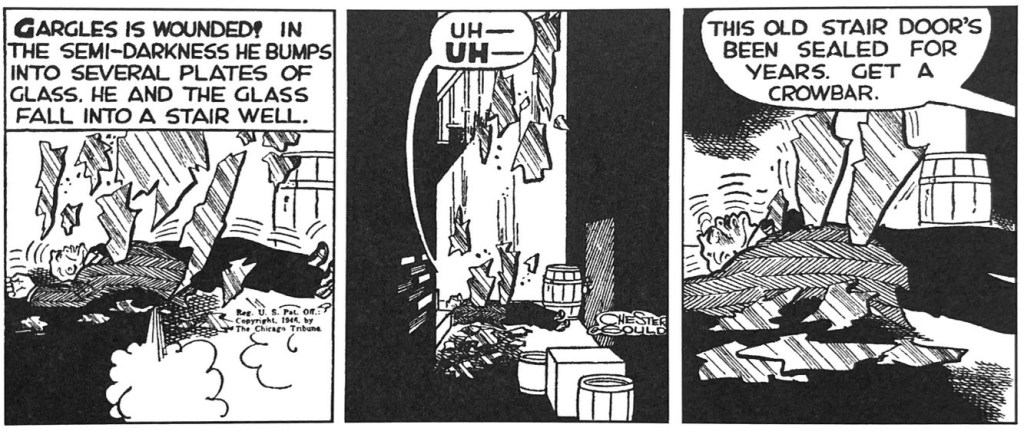

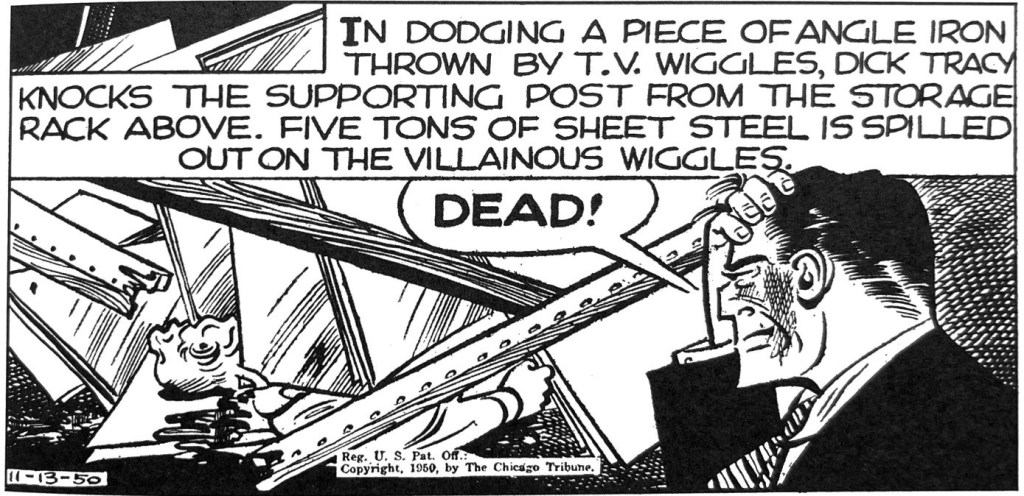

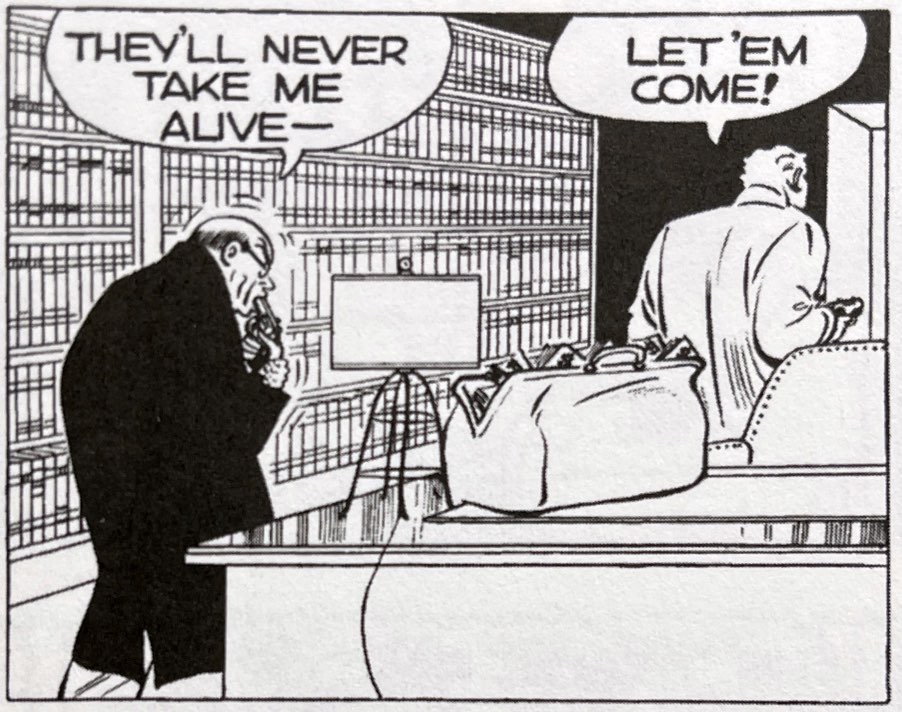

Frost was a regular in the humor weeklies of the 1880s and his influence on the first generation of newspaper cartoonists is apparent here. In just this sequence we can see previewed so many themes and visual tropes of the first decades of comic strips. The comic disruption of middle class stoicism and order with slapstick chaos was the centerpiece of comics. And it was expressed with the cartoonist’s fascination with cause and effect, the physics of exaggerated motion, the shocked response.

The first three reaction images to the poisoned cat seem like Frost exploring with increasing velocity both the shocked facial and physical impacts of the frantic cat. Keep in mind that motion and the art of freezing motion was very much in the air in the late 1870s and early 80s. Eadweard Muybridge had already started his seminal stop-motion studies of animals in motion that impacted both formal and cartoon arts. And while certainly there are precedents for caricatured pratfalls and slapstick in the pioneer Rodolphe Töpffer’s work, Frost’s superb rendering of extravagant cause and effect were helping establish a special cartoon physics that Opper, Outcault, MacDougal and others would further refine in the 90s and 00s.

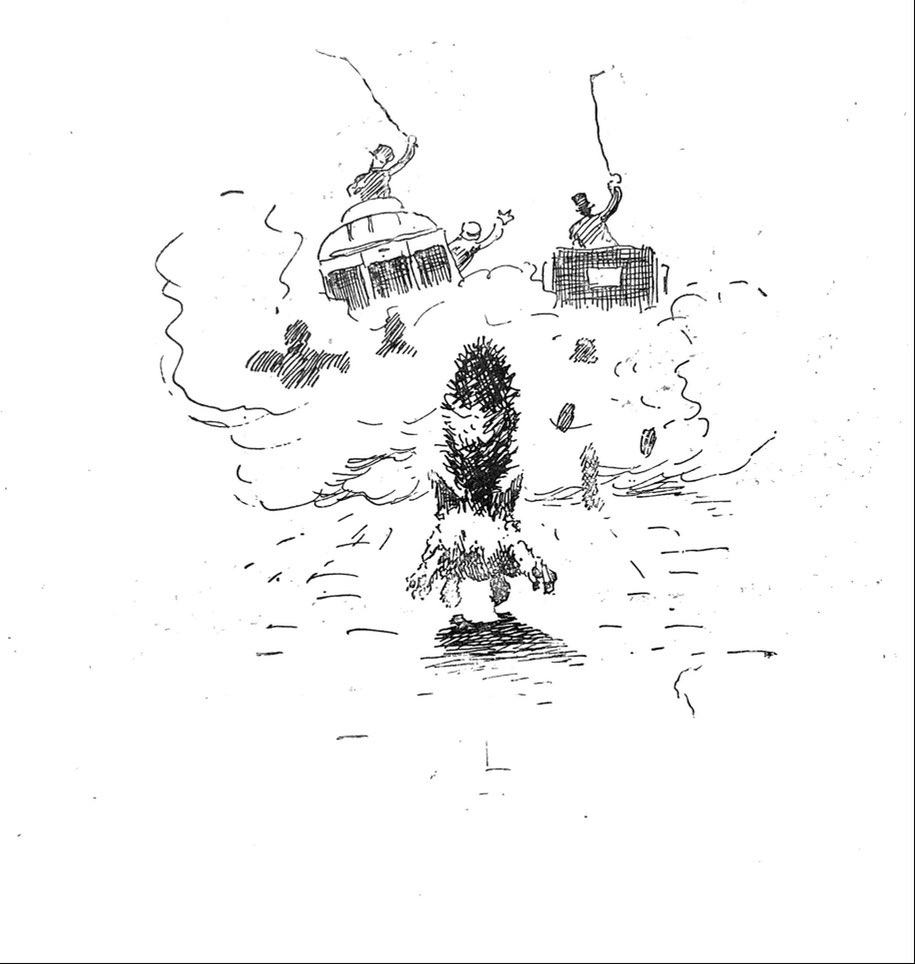

Frost appears to be relishing the mayhem he is creating as he upends the familiar objects and cast of a common affluent household. This is an anarchic convention that many artists took up in the first five or ten years of the next century in middle class bad boys like Little Jimmy, the Katzenjammers and Buster Brown. And Frost is clearly conscious of his own experimentation. The final page in the selection above is entitled “Down the Cellar Stairs (A Study in High Perspective).” In the next-to-last page of the narrative (below) he brings us behind the charging cat to create a new point of view for the audience that also seems to put the viewer in motion as well. Clearly, he knew what he was doing, test driving the potential of caricature to render new effects.

And it all works so well because Frost is just such a polished caricaturist. The bend of the butler’s inhumanly lanky long legs, the slippers shooting from the toppling man in the library, the enormous bedsheets flailing behind the mumps patient are all so convincingly animated. And make no mistake; this is black humor, comic antics bracketed by an accidental poisoning and finally death. The most effective geniuses of cartoon art always have that ability to make the cartoonish still feel real and the real feel cartoonish.

My favorite sequence, however, must be the cat, dog and master in mutual terror erupting from the sewer. All three mouths seem to mimic each other. There is no cause and effect. They are both at once. And yet Frost uses the eyes of each figure to individuate and give each its own voice and character. A decade before the creation of the newspaper humor sections that would nurture a comics universe, A.B. Frost was setting down a comic grammar for this new art to follow.