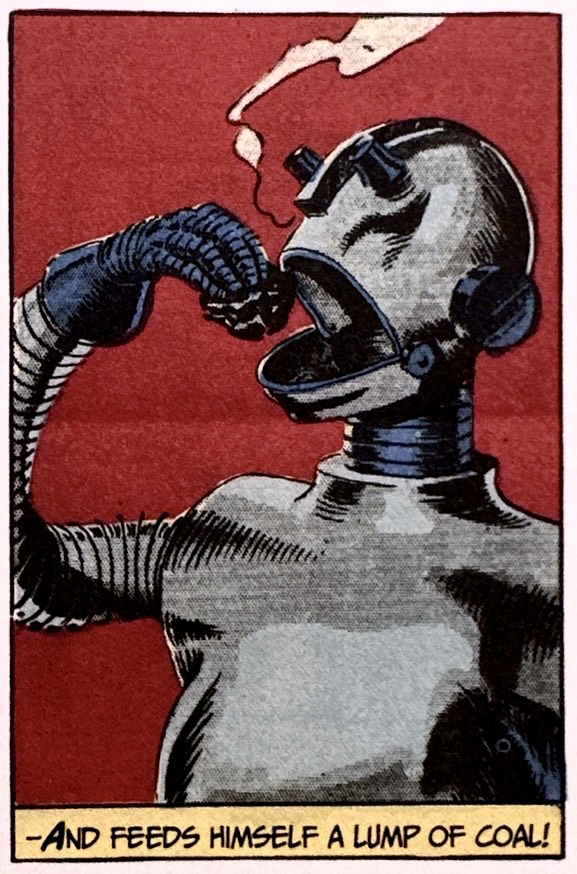

Between August 1936 and March 1937, Mandrake the Magician and his right-hand man Lothar teleported into one of author Lee Falk’s most wildly imagined worlds, Dimension X. It was a universe of altered physics and futuristic super-beings: robotic “Metal Men” made of “animated metal”; “plant people”; ignited, swooping firebirds; man-eating plants; pacifist “Plant People”; and ruthlessly cruel “Crystal Men” who use the skin of captured men to keep their bodies shiny and ready to refract light. Ew! And, of course, no dystopia is complete without hordes of enslaved humans who dream of liberation. It was bonkers, even for a strip that had weird implausibility baked in. And while Mandrake’s side-quest into Dimension X seems like the most fanciful escapism, it was very much of its time.

Continue readingMonthly Archives: September 2023

Sherlocko the Monk: The Great Mystery of the Everyday

The running gag in Gus Mager’s 1911-1912 small wonder Sherlocko the Monk is that this send-up of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous detective rarely uncovers a crime. Mager’s parody sleuth usually unravels “mysteries” around a henpecked husband’s scheme to avoid his wife, an absent-minded fop forgetting where he left the missing object, a neurotic too scared to show up for work. The mystery is really around character and behavior more than around misdeeds. And this is why Sherlocko the Monk is such a satisfying but under-appreciated relic of the first decades of the American comic. Sherlocko pulled together into a coherent narrative whole, themes and narrative conceits that had been germinating in a more haphazard way across many artists and strips since 1895. Sherlocko is the apotheosis of early comics’ preoccupation with social and character types, traits and obsessions. he took that trope and developed it into coherent theater. And along the way Sherlocko maps out where the comic strip had been by 1911 and where it was headed as an American popular art.

Continue reading

Campbell’s Cuties: Wartime Women Had Their Moment

The role of WWII in the history of women, equality and feminism in America is widely known and usually mythologized in Rosie the Riveter tales. With many men abroad, women filled roles in industry and management that typically had been denied them. According to the thumbnail version, newly empowered women suffered a kind of cultural whiplash with the post-war return of men to the States. Industry, government and pop culture generally actively discouraged women from enjoying their newfound role outside of the home in range of unseemly ways.

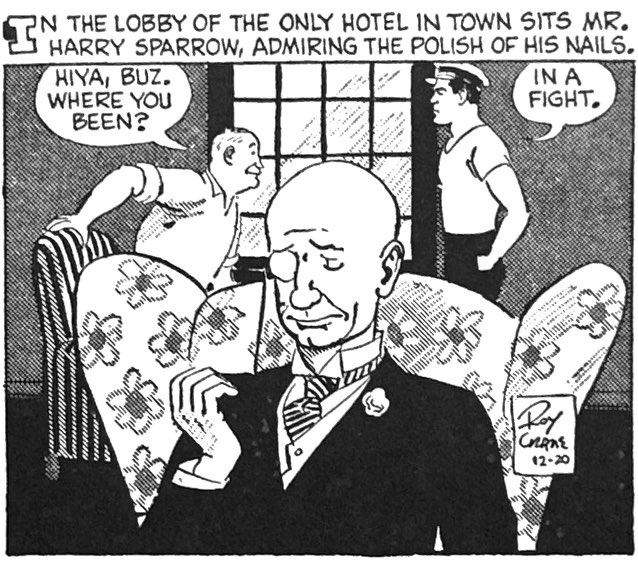

Continue readingQueer-Coding A La 1948: Buz Sawyer Flexes His Pecs

The sublimations of the American comic strip are legion. Whether it is the unbridled eroticism of Flash Gordon or the beefcake of Prince Valiant, the kinkiness of The Phantom or the stripteasing of Terry and the Pirates, the most “innocent” of modern American mass media contained many quiet erotic sub-texts for horny readers across ages and sexes. Case in point, Buz Sawyer in the 1940s. I have no idea what was going on with Buz’s artist Roy Crane and writer Edwin Granberry in the 1947-48 years, but the strip seemed a bit obsessed with gender-bending, sexual stereotypes and masculine identity across storylines in those years. In two adjoined episodes, our two-fisted hero deals with the barely-veiled advances of an effeminate gun-runner and sexual harassment at the hands of a masculinized female Frontier executive. This is one of those many cases where the most reserved and adolescent of modern media, the family newspaper strip, traded in suggestive imagery and innuendo that would never pass muster in other media of the day.

Continue readingRoy Crane: Shades of Genius

Roy Crane doesn’t seem to garner the kind of reverence held for fellow adventurists like Milton Caniff and Alex Raymond, even though he pioneered the genre in Wash Tubbs and Capt. Easy. Perhaps it is that he lacks their sobriety. After all, Crane evolved the first globe-trotting comic strip adventure out of a gag strip about the big-footed, pie-eyed and bumbling Tubbs. But when he sent Wash on treasure hunts and international treks into exotic pre-modern cultures he kept one foot in cartoonishness style and the other in well-researched, precisely rendered settings, action and suspense. It was a light realism, with clean lines, softly outlined figures, often set in much more realistic panoramic backgrounds. This was not the photo-realist dry-brushing and feathering of Raymond, nor the brooding chiaroscuro of Caniff.

Continue reading