The sublimations of the American comic strip are legion. Whether it is the unbridled eroticism of Flash Gordon or the beefcake of Prince Valiant, the kinkiness of The Phantom or the stripteasing of Terry and the Pirates, the most “innocent” of modern American mass media contained many quiet erotic sub-texts for horny readers across ages and sexes. Case in point, Buz Sawyer in the 1940s. I have no idea what was going on with Buz’s artist Roy Crane and writer Edwin Granberry in the 1947-48 years, but the strip seemed a bit obsessed with gender-bending, sexual stereotypes and masculine identity across storylines in those years. In two adjoined episodes, our two-fisted hero deals with the barely-veiled advances of an effeminate gun-runner and sexual harassment at the hands of a masculinized female Frontier executive. This is one of those many cases where the most reserved and adolescent of modern media, the family newspaper strip, traded in suggestive imagery and innuendo that would never pass muster in other media of the day.

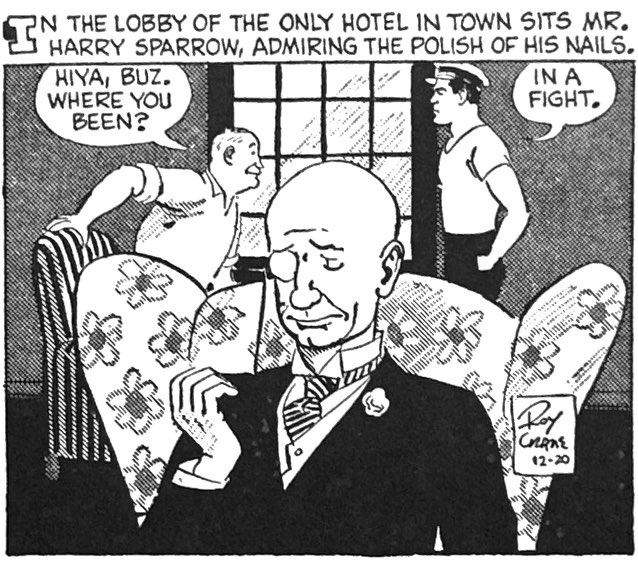

In his post-war career as a third world troubleshooter for Frontier Oil (capitalist imperialism was unabashed back then), Buz encounters soulless arms smuggler Harry Sparrow. Compared to other queer-coded characters in 40s media – think Peter Lorre’s Joel Cairo in The Maltese Falcon or Clifton Webb’s Waldo Lydecker in Laura – Sparrow seems un-closeted. Introduced with monocle and polished nails, Sparrow surrounds himself with fragrant flowers, soft silk and butterflies. If that weren’t enough explicit gay coding, he quickly shows more than a casual interest in beefy Buz, even inviting him to his villain’s lair for a getaway.

The gay-coded villain became a fixture of post-WWII pop culture (i.e. Hitchcock’s Rope and North by Northwest, early Bond nemeses, Leydecker in Laura, etc.). The cultural reasons are likely complex. The increased suburbanization of the nuclear family and corporate, managerial workplaces exerted pressure on received notions of American masculinity, usually associated with force, craft, mobility. Pop culture heroes seemed hellbent on better defining and shaping their masculinity in relation to the supposed perils of feminized men. The cartoon triptych above expresses the anxiety perfectly. Roy Crane expertly gay-codes Harry precisely with a feminized environment of flowers, feline and feathered friends, and transitions into the jarring flash of his lethal, phallic, but concealed and slender cane blade.

From the first panel of the Harry Sparrow episode, Crane juxtaposes male aggression with Harry’s feminized conniving. His introductory image has Buz referring to a recent fight. Harry has a musclebound henchman whose violence is barely contained. And even stranger, Crane serves up ample slices of Buz beefcake as he prepares to spend a weekend with Harry. The two-day stretch of story is remarkably unsubtle. Buz is bathing and dressing in front of his buddy while discussing the dangers of a weekend getaway with the effete and dangerous Sparrow. Our villain’s seductive double entendres thick enough for even the clueless boy-toy Buz to wonder, “What’s this guy driving at?”

Unpacking the motives behind villainy was a familiar trope of post-WWII pop culture, as the psychological arts and an increasingly therapeutic ethos took hold. As Sparrow tells it, his un-principled greed and pompous delicacy were a flight from poverty to restore his regal roots. And of course, there are parental issues, an absent father and sexualized mother. I have no idea where the Harvard-educated script-writer Edwin Granberry picked up these psychological stereotype shards but he seems to have poured them into Sparrow in the space of a few panels.

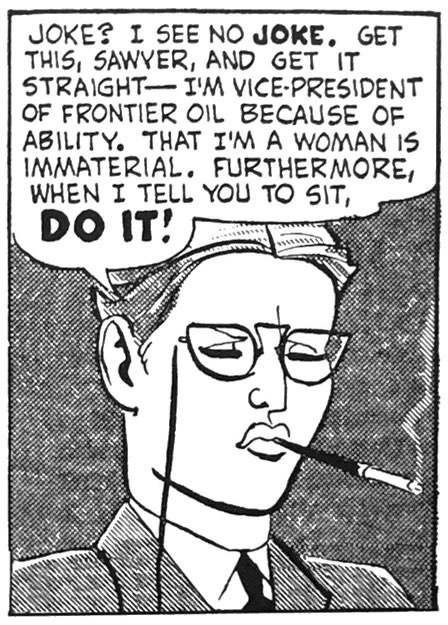

Buz triumphs, of course, and Sparrow’s punishment is banishment to poverty and exile with his henchmen. He does return in a later storyline. Meanwhile, however, Buz reuturns to Frontier Oil’s headquarters, where he has yet another gender-warping encounter – this time with a masculinized female boss, the eponymous J.J. Freeze.

Ultimately, Miss Freeze is sidelined in the episode, so we never get deeper into her background and true intent. But she is around long enough to provide one of the strangest bits of dominatrix harassment we are bound to see in comic strips. Upon meeting Buz, who has been assigned as her bodyguard on a trip to bribe a foreign dignitary, she orders him to strip to the waist and slaps his back to “test” his reflexes.

It may not be coincidental that these strange responses to Buz’s apparently rampant sexuality directly precede his marriage to longtime love interest Christy Jameson. It feels like a final flourish of unfocused sexual energy, perhaps even an impulse to define manhood beyond two-fisted action. By the late 1940s, Buz became at least nominally domesticated. He continued to trot the globe throughout the 1950s, but his material and emotional tether to suburban home and hearth were undeniable. After all, on the rest of the comics page, the action hero was competing with more cerebral and domesticated flavors of male prowess: Rip Kirby, Dr. Rex Morgan and Kerry Drake. In fact everyone seemed to be settling down and settling in to post-WWII American normality. Even Dick Tracy and Abner Yokum ended their prolonged courtships at the altar in these years. The action adventure tended to remove itself from modern times and focus more on the Old West: Hopalong Cassidy, Red Ryder, Lone Ranger, Cisco Kid, Casey Ruggles. And whatever light sexuality was allowed into the back pages of America’s newspapers somehow no longer needed to be as subliminal (and weird) as it had been in the golden age of comic strips.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.