Comic strip history fans should run, not walk, to grab the one indispensable reprint project of this holiday book season, Trina Robbins and Pete Maresca’s Dauntless Dames: High-Heeled Heroes of the Comics (Fantagraphics/Sunday Press, $100). And I don’t mean “indispensable” as a blurb-able critical throwaway, either. The female characters and creators reprinted here from the 1930s and 40s have been “dispensable” in too many histories of the newspaper comic. The central value of this volume is the smart editorial decision Trina and Peter have made here: surfacing strips and artists who have been underserved by the standard anthologies and reprint series. Whether it is Frank Godwin’s pioneering adventuress Connie or Neysa McMein and Alicia Patterson’s Deathless Deer, Bob Oksner and Jerry Albert’s Miss Cairo Jones or Jackie Ormes’ Torchy Brown Heartbeats, the editors have not only featured previously un-reprinted and forgotten material. We get here substantial continuities from each strip that allows a much deeper appreciation for each strip’s character interactions and story arcs than we get from typical anthology samples. You are in the hands of two masters here. Trina has single-handedly championed the history of women comics creators in a number of previous historical and reprint works. And the longtime editor and founder of The Sunday Press, Peter is not only a walking library of comic strip history, but a sensitive curator and restorer. As a book, Dauntless Dames has the same qualities as the heroines it reprints: at once brainy and drop dead gorgeous.

But before digging into the highlights and substance of this important book, some specs on what your $100 investment buys are in order. The 160 page, 13×17 inch tome is formidable and immersive without being unwieldy. It is done in the style of previous Sunday Press Books, but now with the broader distribution reach of partner Fantagraphics. The editors provide concise intros to each strip and artist that leave all of the pages for reprinting excellent restorations, considering the quality of some source material. The 20 or so pages of Godwin’s Connie pop with that deft illustrator’s fine line and mastery of posing. Even the muddier and less accomplished art of Tarpe Mills’ Miss Fury get a fighting chance to demonstrate its noir moodiness. The scale and care of this reprint really opened up Oksner’s engaging use of staging, frame, facial expressions and panel progressions in Miss Cairo Jones, for instance. And for the record, let’s run down the strips reprinted here: Connie, Myra North, Flyin’ Jenny, Brenda Starr, Invisible Scarlet O’Neil, Miss Fury, Deathless Deer, Miss Cairo Jones, Claire Voyant and Torchy Brown. And with the extended selections, Robbins and Maresca have restored to the published record enough of each strip to engage our thinking about what these artists and heroines were adding to the medium and the culture.

To wit.

Godwin’s Connie originated in the late 1920s as the comic strip’s first adult adventuress. At first, she was more of an independently-minded heiress whose situations seemed modeled on the film serial The Perils of Pauline. But Connie Kurridge evolved into various roles as an aviator, reporter, charity worker and eventually sci-fi heroine who goes under the sea, into space and, in the 1936 sequence reprinted here, centuries into the future. In this 2936 Earth, women have been elected to lead and men have been consigned to manual labor and warfare. Godwin’s precise, illustrative technique really shines via alien landscapes, space warfare, massive high-tech cities, etc. Connie herself remains an insubstantial character, more of a reactive milquetoast than a persona. Her independence is expressed mainly by a willingness to enagage with the otherworldly imaginings of Godwin at his artistic peak.

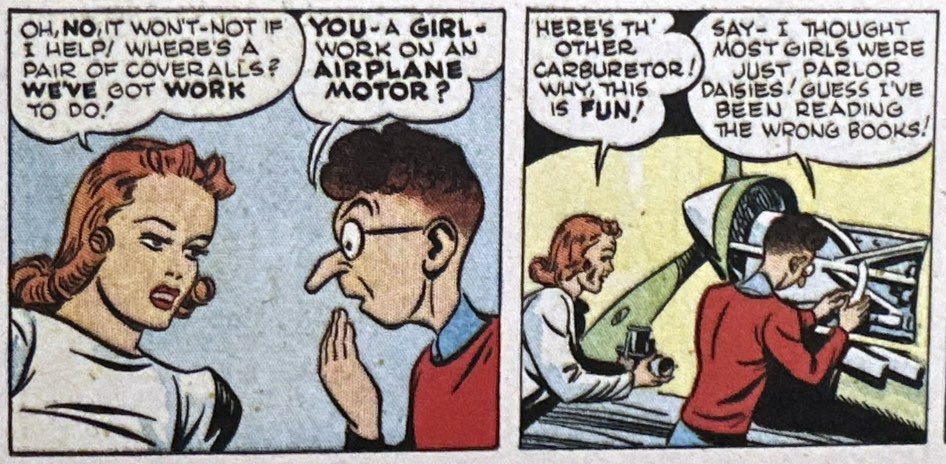

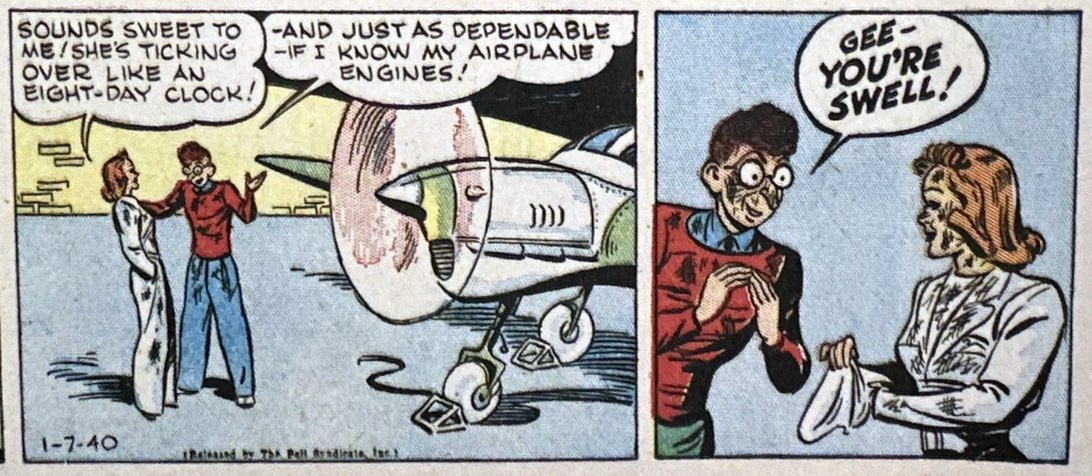

With lesser art but better mystery stories, Ray Thompson and Charles Coll’s Myra North…Special Nurse is like Connie more curious than heroic. This nosey private nurse seems modeled after Mary Roberts Rinehart’s Miss Pinkerton, whose job thrusts her into the role of amateur detective for murders among the rich and famous. More substantial and well crafted is Russell Keaton’s Flyin’ Jenny, whose titular heroine is among the first to self-consciously buck gender conventions. She becomes a winning air racer and a wartime operative who doesn’t shrink from taking up a machine gun. Keaton, an accomplished cartoonist of aviators throughout the 1930s, employed a clean line that seemed to fetishize his precisely rendered aircraft as well as his good girls. Flyin’ Jenny was wartime candy in the way it blended planes and pin-ups.

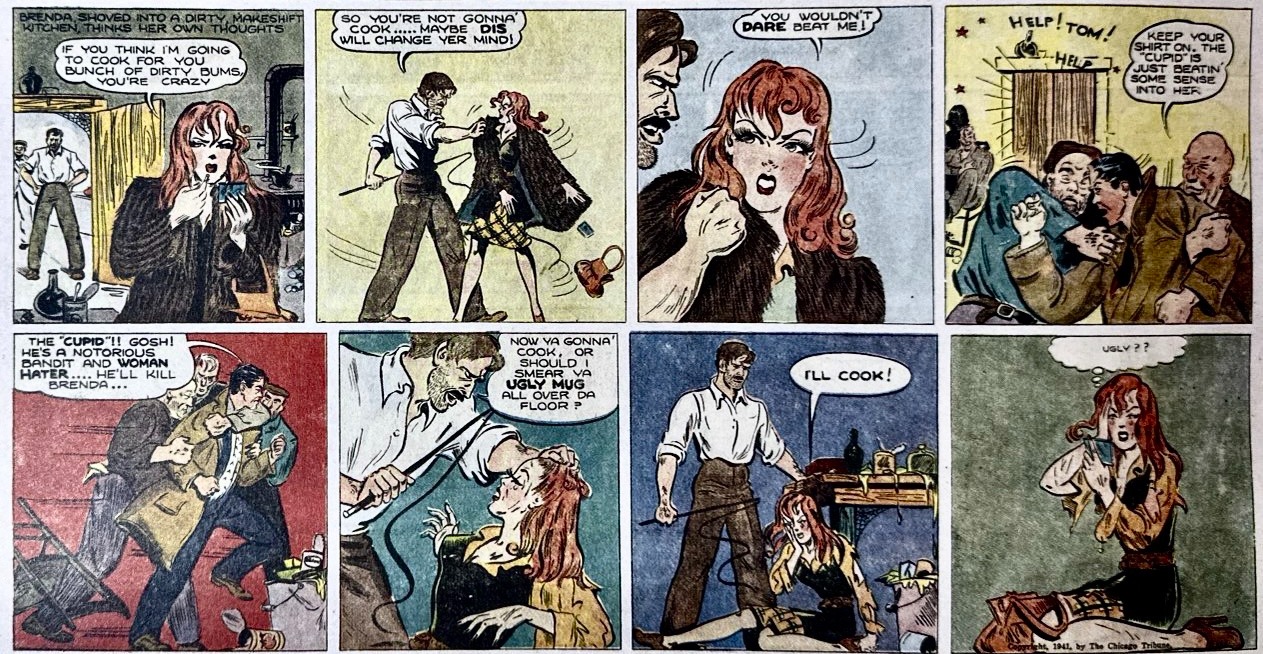

Arguably, Dale Messick’s 1940 premiere of Brenda Starr is where we finally see a well-rounded, ambitious career woman take on the patriarchy. In the 1941 sequence included in this book, Brenda combines her feminine wiles, fashion sense and cunning to penetrate a Nazi spy’s network. This early adventure may not show off Brenda’s ambition and famous temper as effectively as some others, but it does illustrate how the war helped enlist and empower women as home front heroines.

Russell Stamm’s forgotten Invisible Scarlet O’Neil is one of the revelations in Dauntless Dames. Formerly a Chester Gould assistant, a lot of the Dick Tracy visual style is applied ironically to a soft-boiled, soft-hearted heroine. Scarlet was among the first women endowed with a superpower, invisibility, but she puts in the service of everyday folk in trouble. She solves for people unjustly accused, kidnapped pets and a haunted house.

The Library of American Comics/IDW lavished Tarpe Mills’ Miss Fury with an oversized reprint of Sundays in 2011, and I confess being put off from enjoying the strip’s charms by Mill’s poor art skills. The 1944 storyline reprinted here helps open my mind a bit. As Robbins points out, Mills gnashes through some intricate plotting and spends more time honing her arch-villains than developing Miss Fury (a.k.a.) Marla Drake. But to Mills’ credit, she gives her characters self-doubt, introspection and often sharp-tongued repartee. Jealousy, love, double-crossing are all themes that creep into the plots in ways it is hard to imagine from a male cartoonist. As well, this is an early instance of a costumed female hero with a secret identity…and a skin-tight panther suit to boot.

Neysa McMein and Alicia Patterson’s Deathless Deer may be the book’s best unearthed curio. McMein was an accomplished cover artist for McCalls and member of the literary Algonquin Table, while Patterson was daughter to famed Tribune publisher and comics champion James Medill Patterson. While the strip had a unique pedigree, good art and promising premise, it lasted all of nine months. Deer is a murdered princess of ancient Egypt who is given eternal life by a High Priest but only gets revived in the modern world by an archeologist opening her tomb after 3000 years. She and her talking Falcon Horus are fish out of water royalty. Deer trips into conspiracies, jealousies and romance as she poses variously as a dance hall girl, maid and actress. It is a strange brew, but the kind of obscurity worth having.

More to my liking is the edgier, genuinely suspenseful and visually sophisticated Miss Cairo Jones by Bob Oksner and Jerry Albert. Miss Jones is the real thing, a gun-wielding adventuress with solid come-back lines and good aim. When she tries to clear her husband of suspicion of being a Nazi war criminal, only to find that he is one, the crisp journey through villain-filled intrigue and double-crosses begins. Oksner would go on to work in superhero comics, but he is already polished in this short-lived but excellent run from 1945-47. His Miss Cairo Jones should have been a female peer of the post-war adventurers Rip Kirby, Johnny Hazard, Buz Sawyer and Steve Canyon. The strip was that good.

Also well-crafted by a future comic book artist, Jack Sparling’s Claire Voyant was unique in its heroine’s front line involvement in the war effort as an undercover operative in the Pacific Theatre. The smaller sample of this strip is enough to show off Sparling’s channeling of Caniff in rendering faces, panel pace and framing for emotional effect. As is too often true of the comic strip “dames” in this period, Clare may be “dauntless” but she is far from rounded.

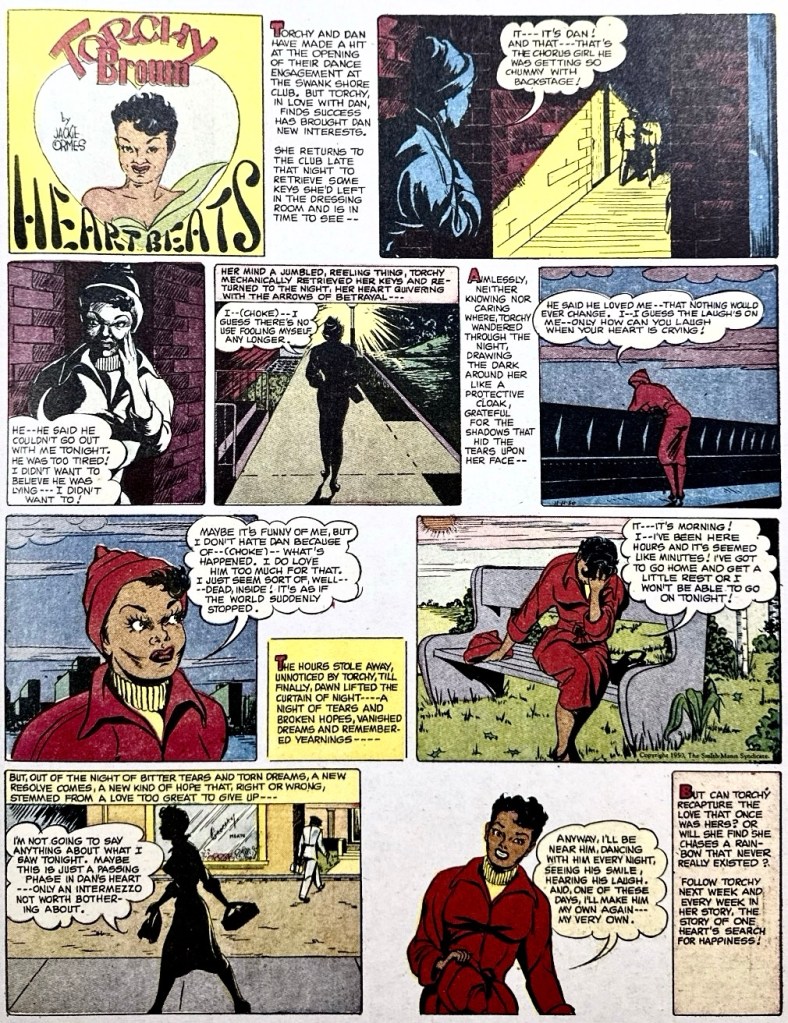

Dauntless Dames ends with Jackie Ormes, who may be the most historically significant artist in this collection. The pioneering Black cartoonist is finally getting her due, in biographical and reprint books. Her gag panels and strips in the major Black newspapers of the 30s through 50s took on racism, civil rights, set fashion trends and even resulted in a very popular Patti-Jo children’s doll. Here we get the second iteration of her Torchy Brown character in the more romantically-aimed Heartbeats continuities of the early 50s. Though slim, this selection reminds us what a thoughtful and passionate artist Ormes was. She puts her Torchy through genuine tragedy and hardship, candid encounters with systemic racism, all propelled by her heroine’s raging heart seeking true love. Every panel is filled with some kind of dramatic tension.

Taken as a whole. there is something both encouraging and depressing about reviewing women’s roles in 30s and 40s comics. Having these characters taking the lead, showing as much ambition as leg, more courage than cleavage, is inspiring. And this collection is an important correction to the standard histories that follow pretty much the same prejudice as newspaper editors – that the comics were aimed at 12-year-old boys. The women artists especially (Mills, Ormes, Messick, McMein and Patterson), brought to adventure strips a different level of introspection and emotional dynamic among characters. And yet the demand for cheesecake, servicing those 12-year olds and their fathers, remains. The lengths to which both male and female artists went to lift these ladies’ skirts and undress them again and again in order to satisfy the male gaze is sobering. And with some exceptions, these feminine leads are bland characters themselves, rarely threatening established gender roles and too often dependent on male muscle to do the heavy lifting. As much as this great and necessary collection elevates the heroic role women played at this moment of pop vulture history, it also reveals that era’s ambivalence towards the female hero. This more complex part of the story is understandably outside the purview of Robbins and Maresca’s task here. But the value of this book is what we do with it, how it makes us open up a richer cultural context.

Again, to wit.

Dauntless Dames is rightly focused on heroines who carried their own titled strips, and the job is reprinting the original work, not analysis. But as it should, this book is “indispensable” because it not only resurfaces important history, but because it is an occasion for rethinking the relationship between comics and their cultural context. Consider how many other female characters of the 30s were coming out from under the typecasting of distressed damsels, flapper airheads and tyrannical wives. I would argue that Little Orphan Annie preceded Connie as the first adventure heroine. The policewoman Molly Day of Radio Patrol was a fully empowered and enabled professional crime-fighter throughout the 1930s. Al Capp’s Mammy Yokum may actually have been the most powerful female figure of the period, the matriarch as super-hero. And Apple Mary, who evolved into Mary Worth, was in her own way an adventuress of the human heart who set the stage for the comic strip soap operas that shone in the 1950s.

And there is a denser cultural context that must surround Robbins and Maresca’s fine work. The rise of the enabled, more powerful, wisecracking woman was driven as much by the Great Depression and WWII as it was by liberalizing ideas of gender. The Depression visibly disempowered and demoralized American men by depriving many of them their identity as providers. John Steinbeck captured this most explicitly in the broken, near-enslaved farmers of Grapes of Wrath and the matriarchal rock that was Ma Joad. On a different social plane, Hollywood gave us resilient, unflappable professional women and socialites (Katherine Hepburn, Claudette Colbert, Barbara Stanwyck, Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo) who gave better than they got from hapless men. Then, with much of the male population activated for WWII, women were thrust into home front jobs of both toil and responsibility. It is not coincidental that most of Robbins and Maresca’s Dauntless Dames span the war years. Women were entering the formerly male domain of comic strip adventure just as they were also occupying assembly lines and managerial offices to replace absent men. But as these strips suggest, it was not without ambivalence in the culture, an uncertainty about whether we wanted American women to be depicted as more thoughtful and capable, less tied to stereotype, or as eye candy in persistent need of male muscle.

That cultural ambivalence with shifting gender roles, and the short lives of most of these strips, is important because the government, industry and the culture made it painfully clear after the war that this emancipation from type for women was not progress, and not permanent. Not coincidentally, few of these strips beside Brenda Starr even lasted into the 1950s. The post-war effort to yank women out of their short-lived self-reliance couldn’t have been more explicit. In order to make way for men returning to the workforce, women were made to feel guilty for their independence and ambition, openly urged to get back into the home. American pop culture rationalized this retreat by even more loathsome means. The “femme fatale” of the film noir era made female sexuality now seem more than impolite; it was dangerous and in need of containment. The witty and capable female leads of the 30s were gone. The bombshell, the dutiful housewife, and the ditzy girlfriend were the more common tropes of film and television. The greatest sitcom of the 1950s, I Love Lucy, was grounded in a single sexist joke. A wife’s careerist ambitions resulted inevitably in slapstick, buffoonery, shame, regret and the loss of her femininity. The great irony, of course, was that this caricature was being played peerlessly by that era’s most powerful, professional and capable entertainer.

I go on about all of this because the complex fabric of historical context is critical to understanding the larger meanings comics generally and of these “Dauntless Dames.” The book is a must-get because the reprints deserve to be seen and appreciated. They have been neglected by other historians and anthologists. But the book is important in a broader way. When you put Dauntless Dames in that larger context, it reminds us that history is not always progressive. It works in fits and starts, progress and backlash. The first wave feminists of the 1960s often went back to this moment in pop culture to retrieve the lost power and elegance of Kate Hepburn, Rosie the Riveter, Brenda Starr, as role models. The first issue of Ms. Magazine in 1972 had Wonder Woman on its cover, a comic book heroine invented in the thick of this Dauntless Dames era, 1941.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: The Revenge of the Reprints: Recent Books for Classic Comics Lovers – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Ella Cinders Deserves Her Moment – Panels & Prose

I cannot wait. Thank you for this fantastic review.