Hate is an easy sell. In the marketplace of hearts and minds, intolerance, grievance, anger are some of the most compelling product features of any cause or candidate that is new to the political shelves. Likewise, simple, high aspirations tend to market more easily. See “Hope and Change.” Appealing to base instincts or ambition and aspiration is Marketing 101 in America’s cultural economy.

Throughout the 20th Century, the causes of democracy, fairness, tolerance, representative government, et. al. have been tougher sells. They are higher concept, more complex messages. But many generations of American propagandists have been taxed with the challenge, especially in times of both hot and cold wars.

“Propaganda” was not always a pejorative. In the first half of the 20th Century it was more of an accepted tactic – the modern way of using new mass media to support a cause. It was a blunt instrument operating on a blunt theory – that the new media channels had a direct effect on viewers’ hearts and minds. In World War I the U.S. Government created the Committee on Public Information (CPI) and in WWII more reluctantly the Office of War Information (OWI) to promote the efforts across all media channels – film, magazines, cartooning, poster art and radio.

In 1938, Americans were seeing horrific news reports of the Kristallnacht raids against Jews throughout Germany, and yet not all Americans seemed appalled, let alone moved to action. Fascist sympathies and unabashed antisemitism here in the U.S. were more rampant at home than we like to remember. In Boston and New York, for instance, teen thugs reportedly targeted and assaulted fellow citizens after asking “Are you Jewish?”

That chill of familiarity you are feeling about now is precisely why Rafael Medoff and Craig Yoe’s Cartoonists Against Racism: The Secret War on Bigotry (Dark Horse Books/Yoe Books, $19.99) is self-consciously timely. They chronicle and reprint the cartoons commissioned by the American Jewish Committee’s (AJC) organized effort to fight antisemitism by denouncing racism generally and promoting democratic principles of unity and tolerance. That approach was inspired by an advertising executive recruited by the AJC, Richard C. Rothschild.

Rothschild was an interesting figure who is only described by Medoff and Yoe as a former advertising executive. Before leading the information and education wing of the AJC he had been at J. Walter Thompson as an account executive and then leading the New York office of the Lord & Thomas agency, according to his NY Times obit in 1986. He also helped in the WWII war effort to explain to Latin American countries the democratic aims of the world war. Before and during the war, Rothschild was dedicated to using the tools of mass media for persuasion. But after the war he turned to big ideas, writing several books on philosophy and religion.

He brought an adman’s special savvy about market and audience to the antisemitism challenge. According to Medoff and Yoe’s able introduction, Rothschild’s central strategy was to wrap antisemitism in the larger problem of American racism. He wanted to avoid defensiveness and merely countering (thus restating) the bigoted stereotyping that associated Jews with everything from Communist sympathies to banking conspiracies. At the same time, however, he warned against blanket indictments and finger-wagging at America’s longstanding predilection for racism. Instead, he argued “the anti-Semites themselves had to be put on the defensive. They had to be the ones put in the criminals’ dock.” And yet, he didn’t want the focus to be on antisemitism alone, and especially not on Jews in particular. He feared backlash and resentment against what might be taken as special pleading for a select population.

Rothschild’s strategy was sophisticated at the time, and certainly foreshadowed even current arguments about how best to beat down American bigotry. How do you prosecute widespread bad ideas without demonizing and alienating the persuadable Americans who entertain those ideas? As well, embedded in Rothschild’s fears of backlash are ongoing concerns about assimilation into the national “melting pot.” This is one of the reasons, Medoff and Yoe tag this AJC effort as a “Secret Jewish War on Bigotry.” Much of the Committee’s work was done through partner groups like labor unions and generically-named dummy organizations to avoid direct attribution to the AJC.

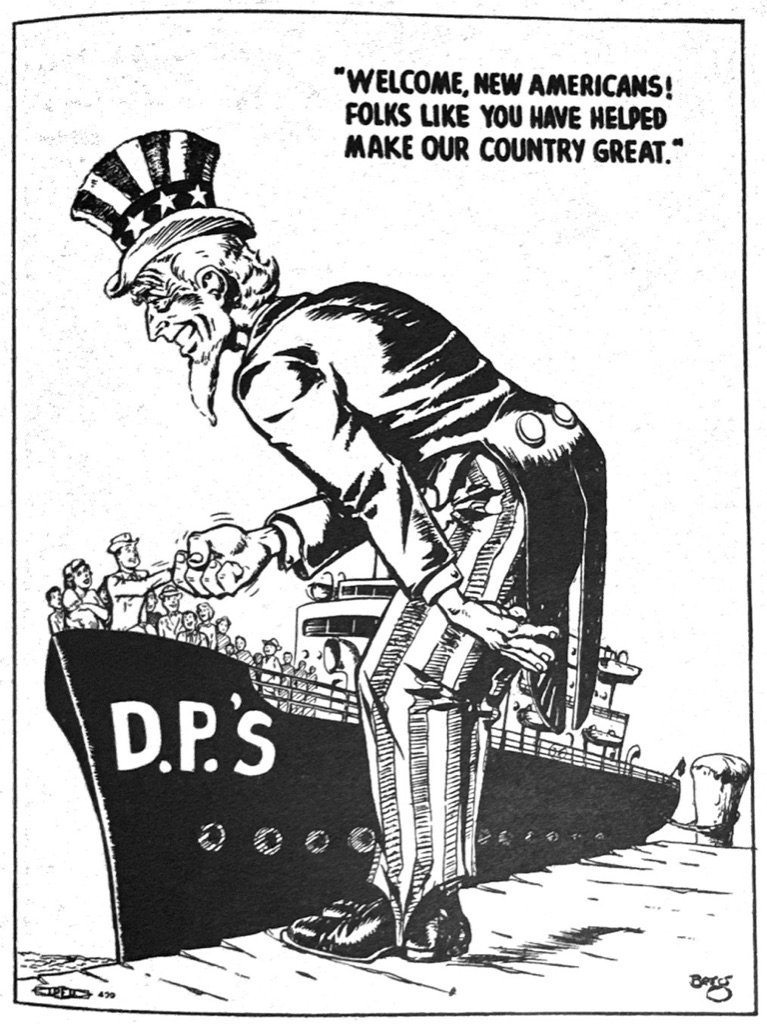

The result of Rothschild’s market-savvy was a campaign that promoted American unity, democratic principles of tolerance and demonized racism generally rather than antisemitism specifically. Just before and throughout WWII, the AJC commissioned a range of media – PSA magazine and newspaper articles, radio spots, posters, and, the focus of this book, comic panels and strips, even comic book stories. Their work can be found in everything from True Confessions romance magazines to Superboy comic book stories.

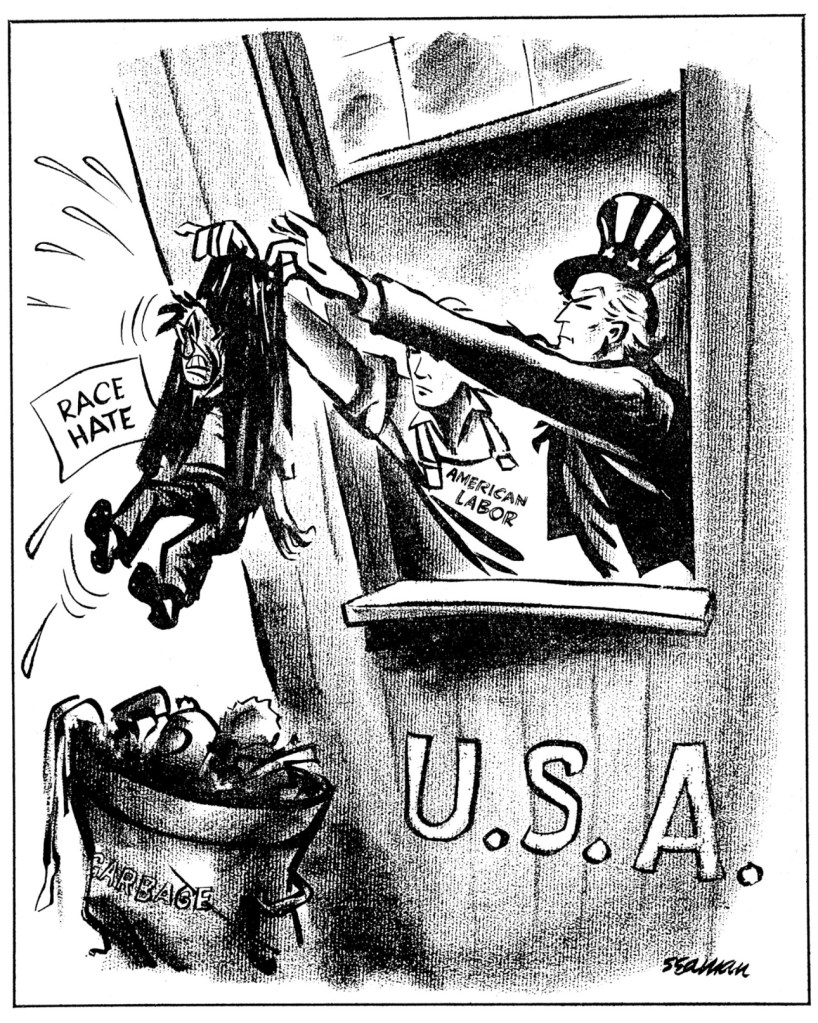

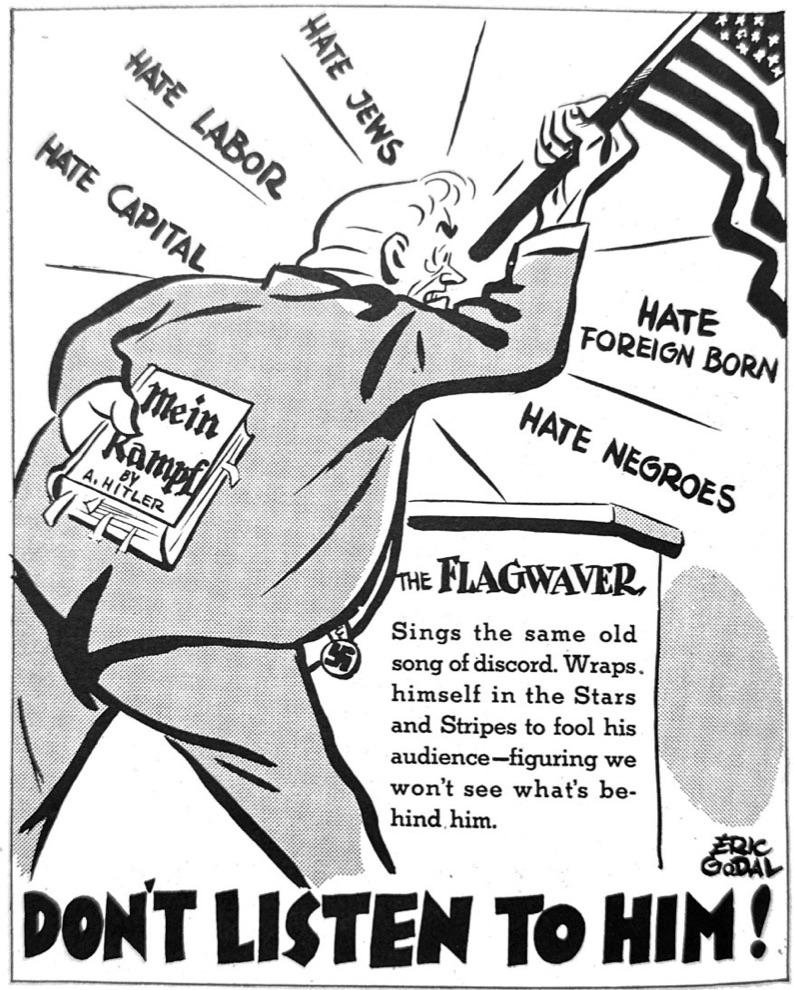

Most of the samples reprinted in Cartoonists Against Racism are in the familiar editorial cartoon format. Bigots and fascists are clearly labeled, as are the representative forces of democratic decency. In one panel, Uncle Sam is posting a “Contagious Disease” warning on the house of a rage-faced homeowner, labeled “BIGOTRY”. “Quarantine Him!” the cartoon is captioned.

Much of the work is as unsubtle as one would expect from such self-consciously ideological art. But Medoff and Yoe have featured the work of strong cartoonists who do their best to rise above didacticism. Bill Mauldin, for instance, has a scruffy chap asking a couple of returning GIs he meets at a service station, “Musta been purty awful havin’ to mix them there iggerant undedicated furriners.” Most of these cartoons lack Mauldin’s talent for irony, however.

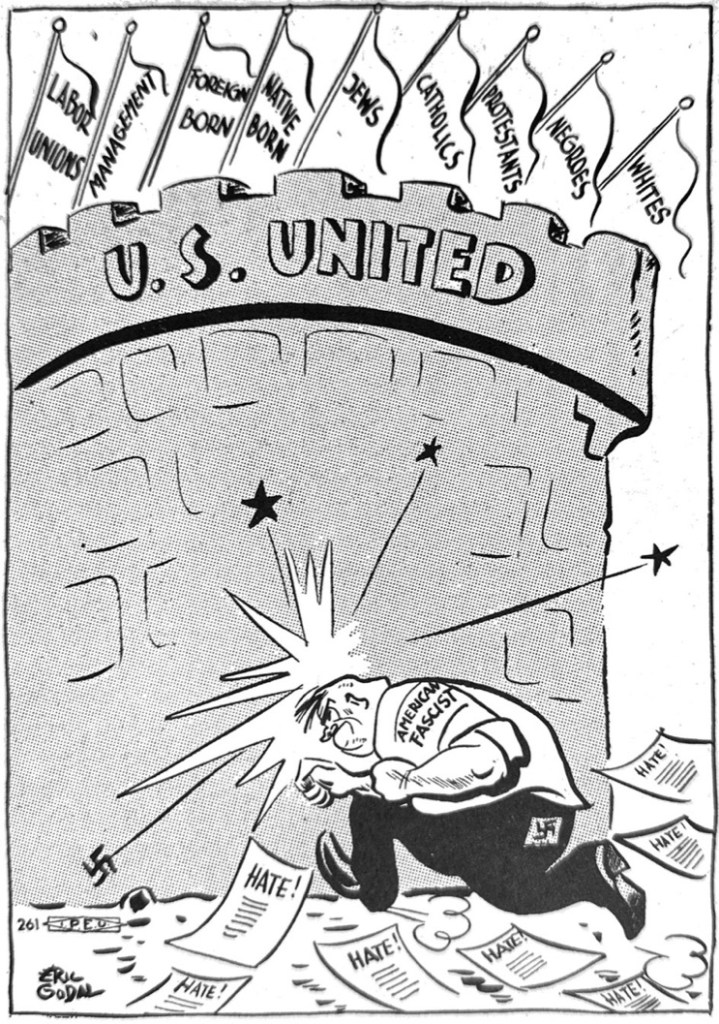

Characterizing bigots as un-American seemed to be the persistent theme. Cartoonist Carl Rose actually created an ongoing character, Mr. Biggott, drawn as a pencil-thin, blue-blooded scold with a cobweb arcing off the top of his pointy head. In one of the most expressive simple cartoons, Eric Godal draws an oafish, overfed “American Fascist” charging headlong into a “U.S. United” castle parapet flying the flags of ethnic and religious groups. “Let him beat his brains out” the cartoon advises. It is one of those rare political cartoons that explores a specific political tactic.

Included in the tolerance promotion effort were familiar names like Mac Raboy, Dave Berg, Robert Osborn, Frank Hanley and Godal, who was a genuine nemesis of the Nazis and fled Germany after caricaturing Hitler.

While the art in this volume ranges from good to middling political cartooning, there are interesting experiments that tried to think through techniques of cartoon propaganda.

Journeyman comic book artist Sam Glankoff illustrated a famous full color 7-pager called “They Got the Blame.” In 1943, its illustrated chronicle of scapegoating across history foreshadowed in approach and artistic stylethe Classics Illustrated series.

Using the Ripley’s Believe It Or Not style, Rothschild and his team created an “American Sidelights” series of PSA cartoons. Each oversized panel included three bits of American history trivia, only one of which highlighted tolerance principles. The theory was that an unabashed tolerance-themed PSA would be resisted by readers as “preachy.” Folding the intended message among unrelated items would lower readers’ resistance.

Cartoonist Robert Osborn created a controversial booklet of image and verse that used visualizations of bigoted stereotypes as a way to mock intolerance, but it was too easily misread by surveyed readers as a racist tract itself. The fact that the AJC even did reader surveys to such an experiment in persuasive cartooning shows how seriously Rothschild was bringing the methods of modern advertising to his task.

And like any good adman, Rothschild insisted that his campaign had impacted popular sentiment. Antisemitism in the U.S. did indeed decline after the war. But as Medoff and Yoe wisely conclude, many larger post-war social and cultural forces were moving the nation in that direction.

The laudable project in Cartoonists Against Racism does resurface the perennial question of how imagery argues. We know that visual propaganda can be enormously effective on both an ideological and aesthetic level, especially when those two qualities combine well. The graphic impact of Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will married form to fascist sensibilities masterfully. The Soviet Union’s official socialist realism aesthetic — again, forceful shapes, generalized imagery, forward movement — embody Communist culture and ideas. Principles of mass, uniformity, progress, power, stability, order, selflessness, collectivism, etc. all can be found especially well expressed in the best of totalitarian and fascist art. Simple, instinctual, emotional appeals visualize well.

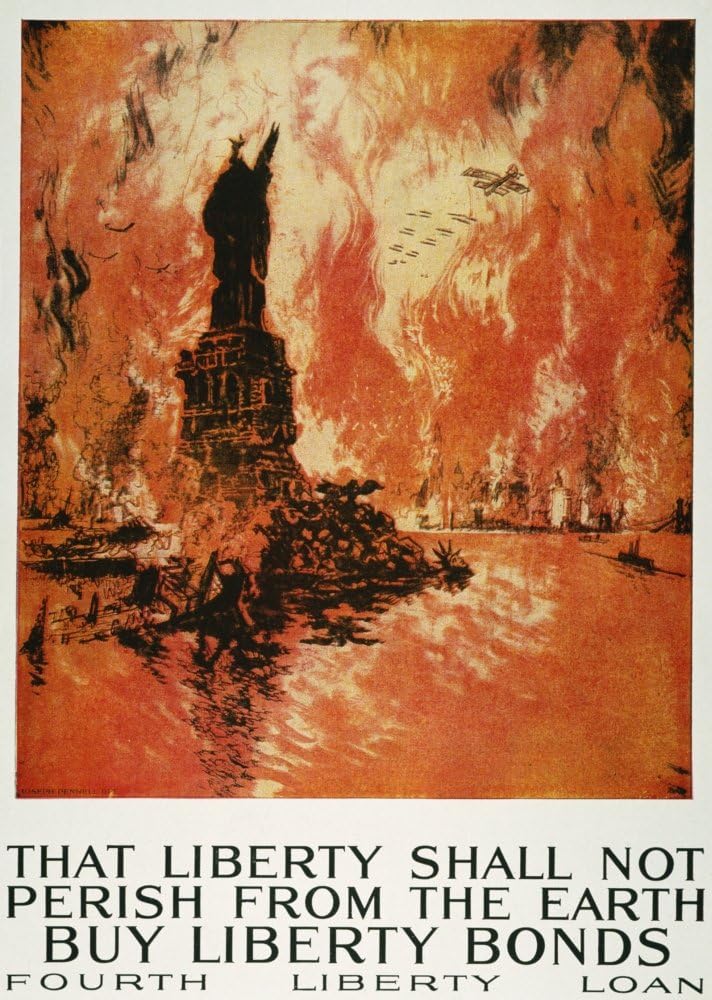

Cartoonists Against Racism does raise the question in my mind about how best to represent arguably more nuanced ideas of democracy and tolerance. In historical memory, WWI is tagged as “the war to save democracy,” while WWII is often described as a “war against fascism.” It is interesting that some of the most iconic war posters of the 20th Century come more from that first war. James Montgomery Flag’s “I Want You” recruiting poster is the best remembered. But many artists working for the CPI’s poster division used the female form deftly. Red Cross nurses became maternal revisions of the Gibson Girl, arguing implicitly that the war effort was humanitarian, nurturing. A more muscular femininity was invoked by heavy use of Columbia and the Statue of Liberty as icons of democratic principles. Compared to what I see in the poster and cartooning art of WWII in books like Cartoon for Victory, WWI artists were both creating and recalling a more sophisticated visual vocabulary to represent a war against the “Hun,” and for Progressive Era democratic ideals. WWI poster art made their case by invoking the existing iconography of democracy. Perhaps the most powerful war poster was Joseph Pennell’s “That Liberty Shall Not Perish From the Earth.” It was a dystopian image of Manhattan in flames and a destroyed Statue of Liberty shorn of head and torch. The monochromatic use of color, composition, symbol, modernist art style, plus the decapitation motif, build a gut-wrenching American nightmare.

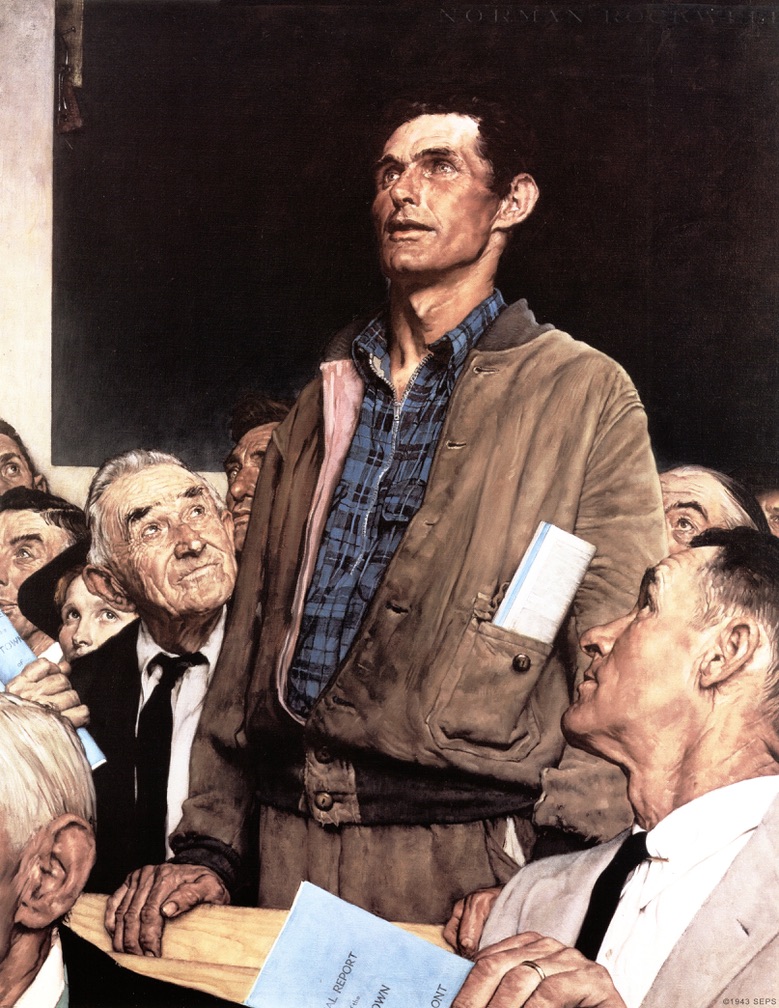

Which is not to say WWII was bereft of smart illustration. J. Howard Miller’s “We Can Do It” image of a muscle-flexing female factory worker became a mainstay of the 60s/70s Women’s Movement. Norman Rockwell’s masterfully wry “Rosie the Riveter” not only makes her war work look offhanded and effortless, but does so using Mein Kampf as a footrest. For all the unfair grief Rockwell suffers as mawkish and sentimental, his talent for visualizing an idea is stunning. It was during WWII that he imagined FDR’s declaration of our “Four Freedoms” in a series of paintings that remain iconic. In my mind one of the greatest expressions of participatory democracy remains his ”Freedom of Speech.” That gaunt working man standing amid a crowd of expectant, respectful, judging citizens – all more formally dressed, is a testament to equality. The man’s hands clenching the rail with nerves even as his bright fixed eyes show principle and confidence in what he is saying, dramatize the complex feelings of having your say within and against the crowd. The folded magazine jutting from his pocket shows that this is a literate citizen who has read and processed information and now asserts his thoughts. So much nuance is there about what democracy feels like.

I don’t mean to recall some of these greatest examples of American propaganda to in any way diminish the work of the AJC and these cartoonists. The AJC artists were responding to a worldwide crisis for Jews and humanity. They were trying mightily to leverage the tools of political cartooning to align antiracism with democracy and American identity. And in our own critical moment in defense of these principles, even the best of their work reminds us how challenging it is to illustrate ideologies of decency.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Shelf Scan 2024: Necessary Reprints – From Anita Loos to Betty Brown – Panels & Prose