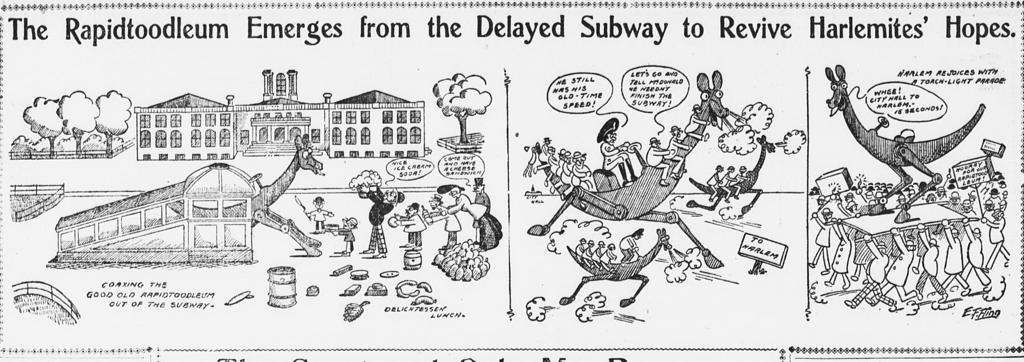

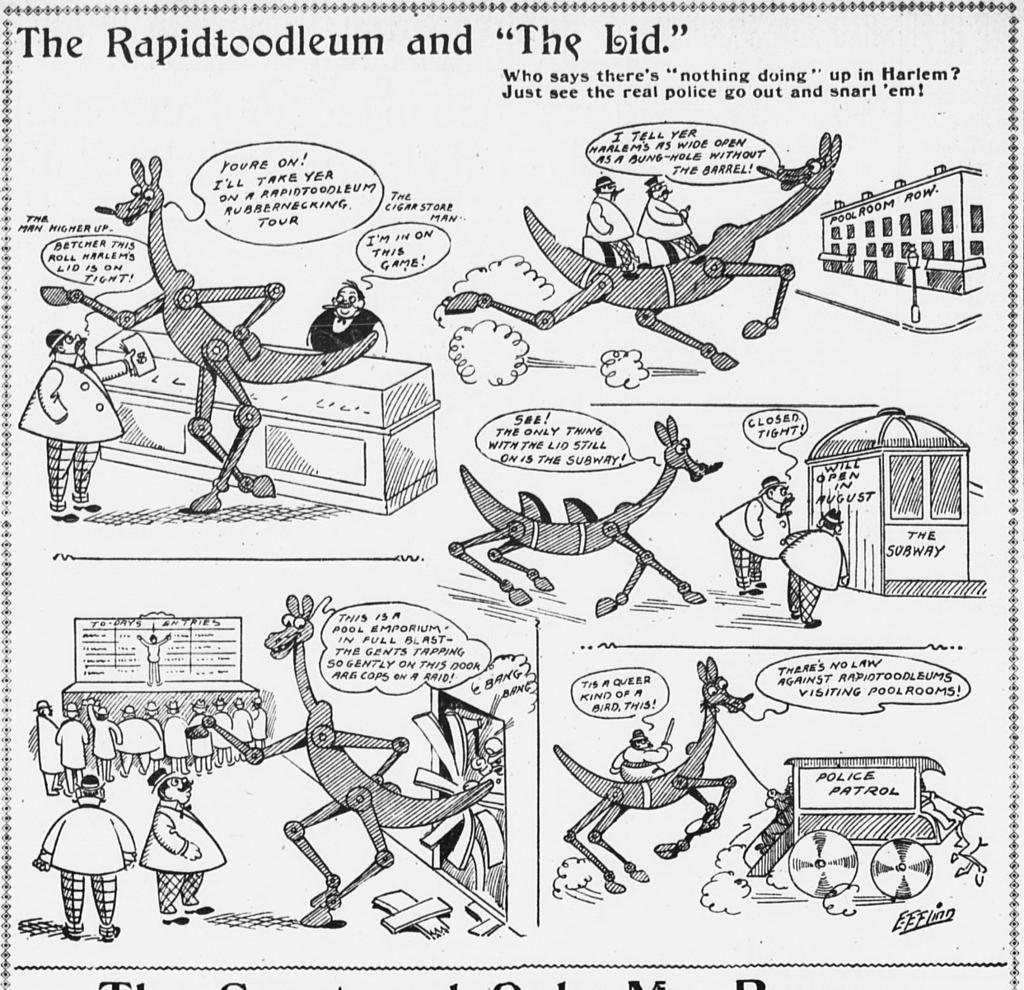

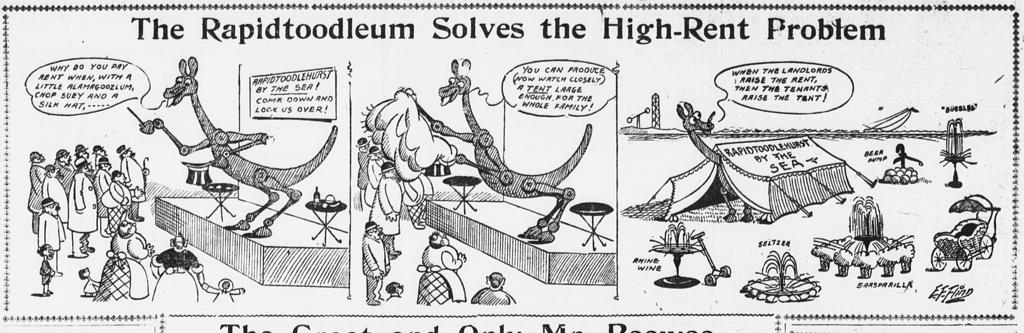

In the New York World on April 5 1904, a giant but apparently friendly robotic beast vaulted from an unfinished New York City subway entrance to address some of the city’s most pressing concerns. Daily, and for the next week, this cartoon “Rapidtoodleum” offered rapid transit that solved for a much-delayed subway project, exposed gambling in Harlem, proposed an alternative to overpriced city housing, outpaced a newfangled automobile, and lampooned the florid fashion in women’s hats.

Rapidtoodleum was just one of hundreds of short-lived comic strip ideas that the first generation of newspaper cartoonists tested in the first decade of the medium. As many comic strip historians argue, the post-Yellow Kid years (1896-1910) were a fertile, boundless period of experimentation among early newspaper cartoonist grappling with the possibilities of this wildly popular art form. Rapidtoodleum’s inventor, Ed F. Flinn (b. 1880), was one of the staff artists churning out new strip ideas good and bad. Starting as a newspaper illustrator in San Francisco, he migrated to New York in the early 1900s and inked multiple strips for The New York World. Most notably, he was the inaugural artist of The Importance of Mr. Peewee, which eventually became the first regular daily newspaper strip. In fact, for its week-long run, Raipdtoodleum ran atop Mr. Peewee, which by then was being drawn by Ferd Long. But, by comparison, Rapidtoodleum is a trifle, a promising premise that seemed to run out of ideas by its sixth and final episode. Still, it underscores some of the conceits and novelties of those years.

Like the reportage around it, the first decade of newspaper strips really took the city around it as its main subject. As we have argued here, in order to understand the public embrace of the comic strip form in the early 20th Century, you need to grasp how the tone, the speed, the crowdedness, the architecture, the dialects, and the complexities of ethnic and social class were at the center of early cartooning. The comic strip was addressing aspects of modern existence that were hard to capture so succinctly and viscerally in other media, and in ways that both confronted and soothed those realities.

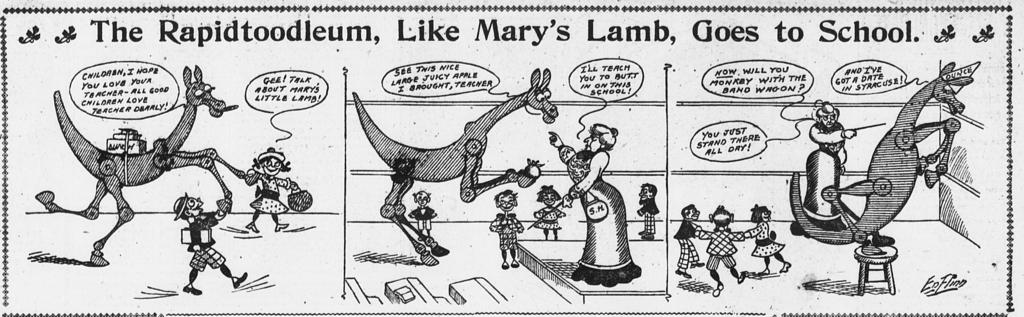

The Rapidtoodleum is a kind of throwback automaton, a cartoon fantasy that marries the modern with the pre-modern. By 1904, the war between automobile and horse was at its peak, and it was emblematic of the tectonic shift from an agrarian past to an urban and fully industrialized America. Cannily, the Rapidtoodleum has it both ways. Flinn’s steed, both googly-eyed and robotic, barges into different aspects of modern urban life, at different times arrogant and humbled, resentful and satiric. The strip makes several references to the much-delayed, budget-busting New York subway project. He crashes the emerging consumer culture and its addiction to fashion and prestige by tossing a salad into a hat decoration. He mocks the perennially delayed promise of underground mass transit by getting from Harlem to City Hall in 15 seconds. This talking, smoking, boastful and even snarky robot stallion feels like a clever rejoinder to the new age of engineering, consumption and technological hubris. Flinn imagines a machine that is all too human in so many ways.

We don’t’ know if Flinn had any long range ambitions for his inspiration. It seems like it could have had legs. A wiseass, robot horse in the new city could go in a lot of directions. But as is, Rapidtoodleum is a good example of how early newspaper cartooning reimagined the city experience, the environment of nerve-wracking change and challenging social environments, in manageable ways.

The newspaper comic strip was the first of several 20th century mass media that Americans embraced fully and with lightning speed. But why? What was so special, impactful, attractive about this medium that helped establish it so quickly as a staple of Americans’ modern media diet? I would argue that it was a singular medium in bringing to bear on modern American life a spirit of whimsy, nonsense, excess, even violence and vulgarity that American literature, film, magazines, radio or TV never approached. It was for the 20th Century what tall tales, regional dialect humor, vaudeveille were to the 19th Century – meaningful, necessary nonsense.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.