The turn to photo-realism in the adventure comics after WWII is well-documented and obvious in any review of the major strips. Alex Raymond’s Rip Kirby, Warren Tufts’ Casey Ruggles and Lance, Leonard Starr’s On Stage, Stan Drake’s Heart of Juliet Jones, John Cullen Murphy’s Big Ben Bolt are just some of the clearest examples. The stylistic foundation had already been set in the 1930s, of course by Noel Sickles (Scorchy Smith), Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates) and Hal Foster (Prince Valiant). They moved adventure strips away from the more expressionist modes of Gould and Gray, or the cartoonish remnants of Roy Crane (Wash Tubbs and Capt. Easy) or the sketchy illustrator style of a Frank Godwin (Connie). .But it is really in the post-war period that we see a clear ramping up of fine line, visual detailing, naturalist figure modeling and movement, as well as full adoption of cinematic techniques.

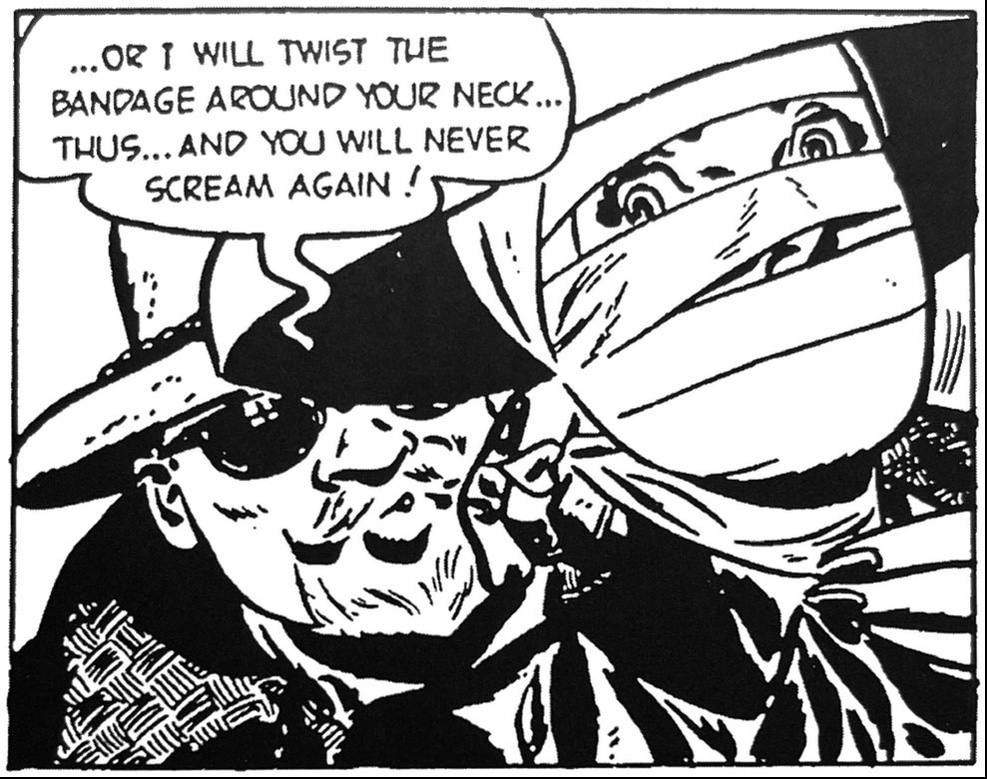

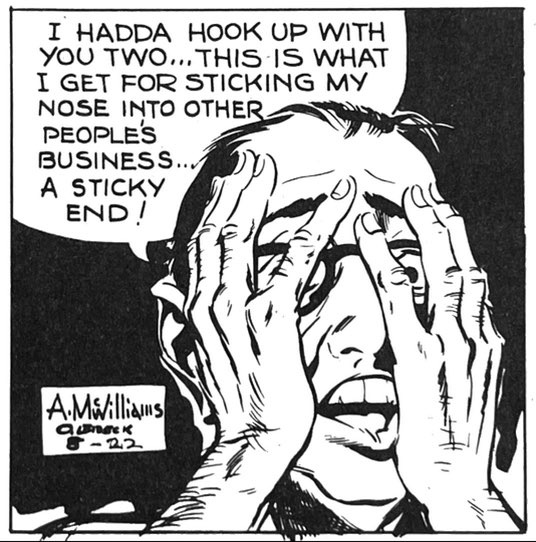

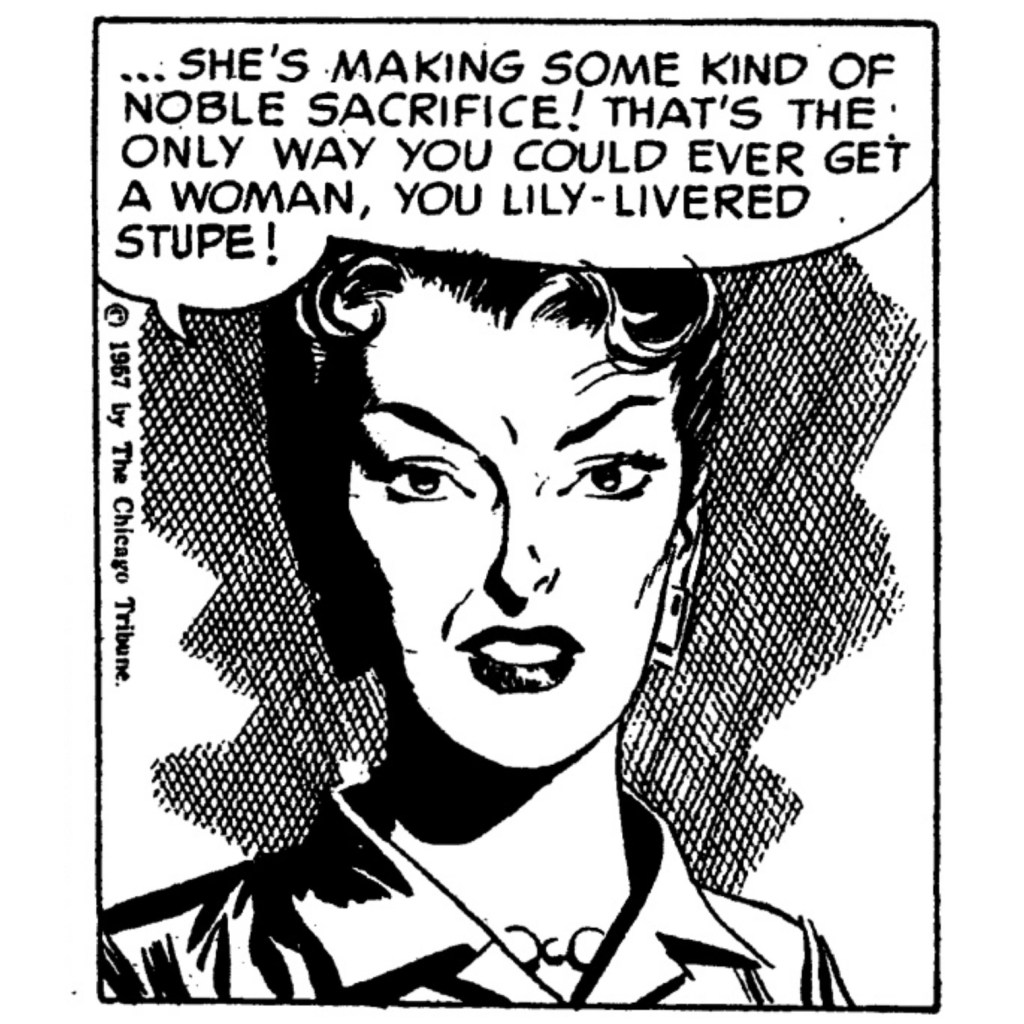

But as I work my way through many of these 50s adventures, it is the pronounced and effective use of the close-up and emotional expression that really strikes me as a signature of this era. In the first decades of the American comic strip, few artists had either the artistic facility or perhaps the narrative impulses to use facial expression to add depth or impact to story. Some were better than others, of course. As Hal Foster matured, he occasionally brought the frame in tight to define the villainy of his rogues. And Alex Raymond was adept at registering the emotional dynamics of menace, eros and humiliation as punctuation to his masterful action sequences. And while most comedy strips used broad, stereotyped reaction to screwball antics, Al Capp was a notable exception, as he was a devotee of facial expressiveness.

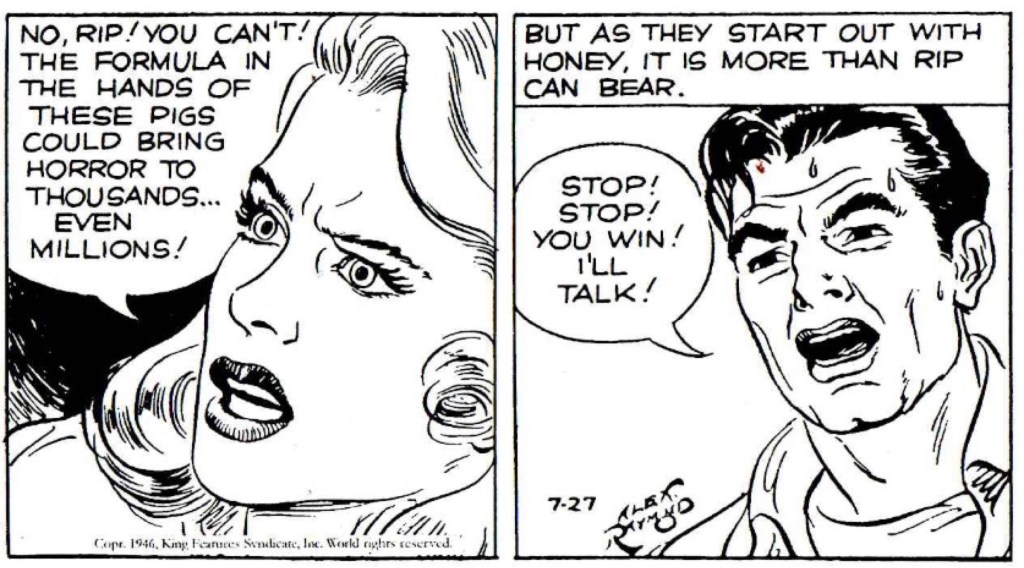

But I think you can argue that many of the notable adventure strips of the later 40s and 50s started relying more heavily on facial expressiveness as part of the narrative palette than ever before. Even in the early years of Raymond’s Rip Kirby, in 1946, you can see him using the tight frame and faces to communicate emotion in a way even he hadn’t used a decade before.

Raymond used close-ups and faces to dramatize dialogue, give feeling to language. In other words, he was letting his characters act visually.

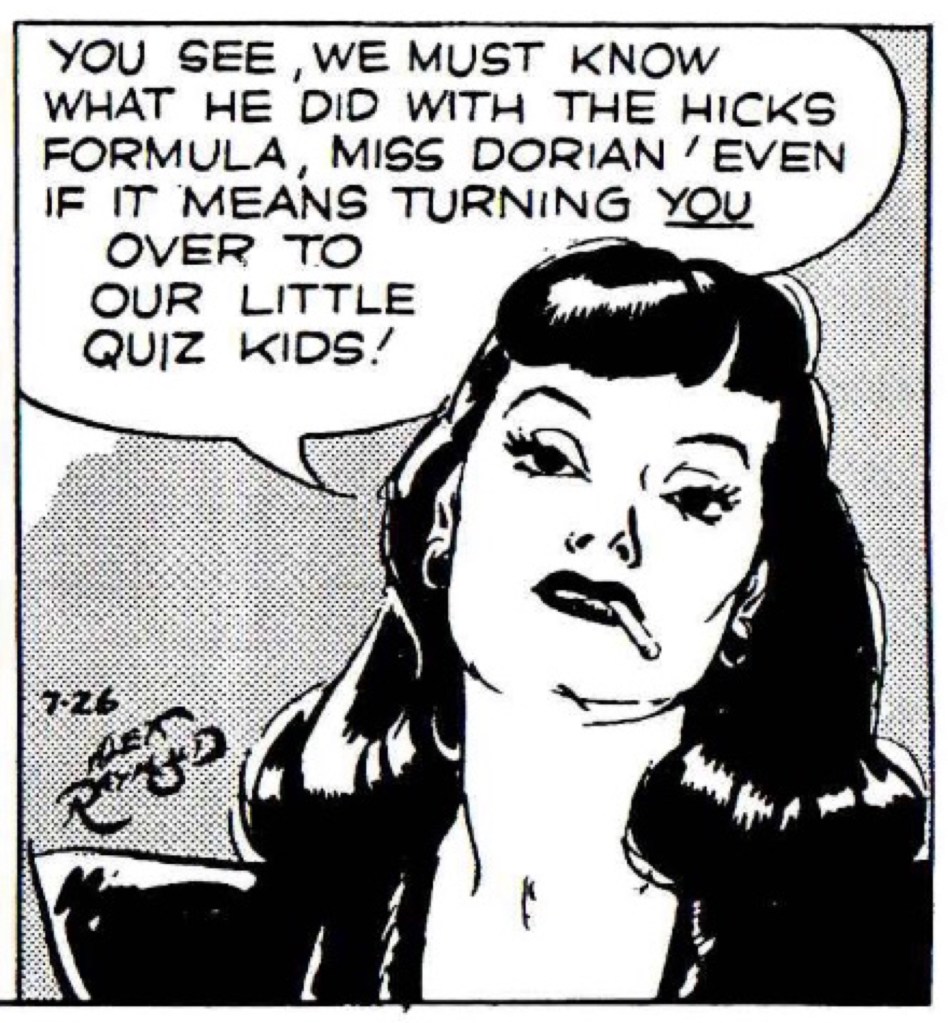

Even the best American cartoonists tended to use their drawn figures more as mannequins voicing dialogue than actors whose faces added layers of meaning to the script. Both comic and adventure artists were at their best putting cartoon characters in physical action, whether screwball slapstick or dramatic violence. Compare, for instance, Raymond’s use of faces in the post-war era to a comparable master, Milton Caniff, in Steve Canyon circa 1947.

Caniff certainly did use timing and expression at times. The first two-panel sequence above is a delicious bit of business in that narrow range Caniff allowed his women to perform – stereotypical competitive cattiness. But the second panel shows his more common use of figures and faces, stiffer puppets whose dialogue carries the emotional weight of the scene.

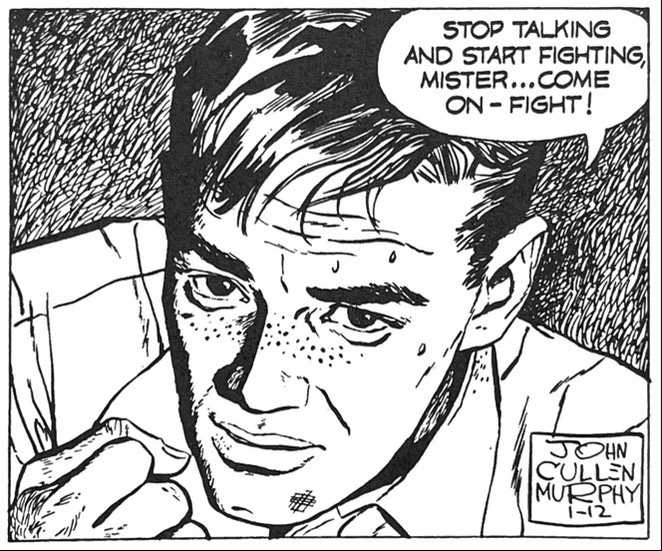

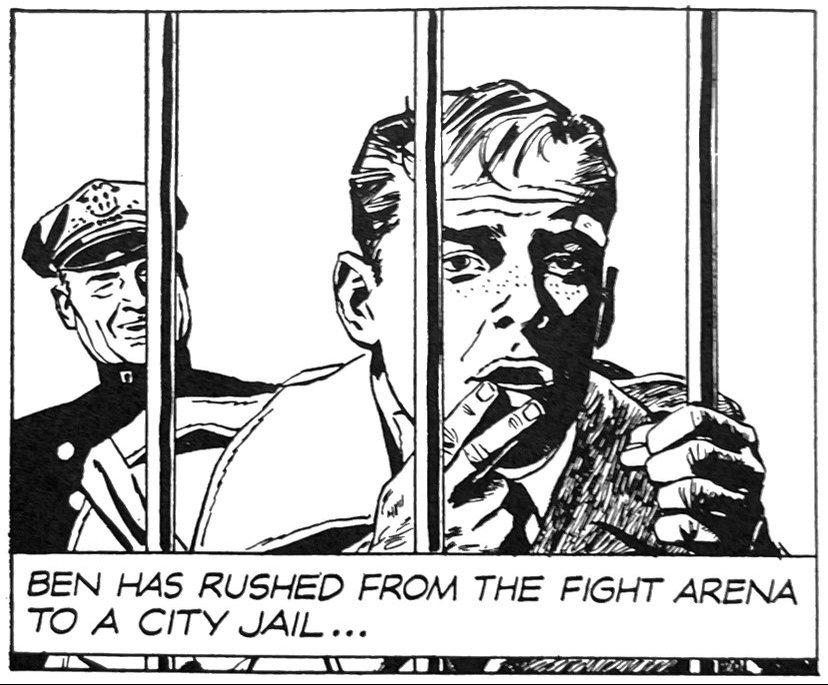

The emerging 50s style was not only bringing the “camera” in closer to characters, but using the tightly cropped panel to pull us into the drama of a story in a more visceral way. One of the best post-war cartoonists, John Cullen Murphy, brought the close-up to another level sensitive boxer Big Ben Bolt. Murphy’s characters don’t just dramatize feeling with their faces but peer from the page at the viewer, courting our empathy.

Facial expressiveness and the photo-realistic close-up was embedded in the visual language of 1950s adventure. We see deployed with varying degrees of talent across Johnny Hazard to Cisco Kid, Twin Earths to Beyond Mars. But across the board we are seeing artists animate the comics page and their own characters with a level of emotive power and personal identification we simply don’t see in the “golden age” of adventure in the 1930s.

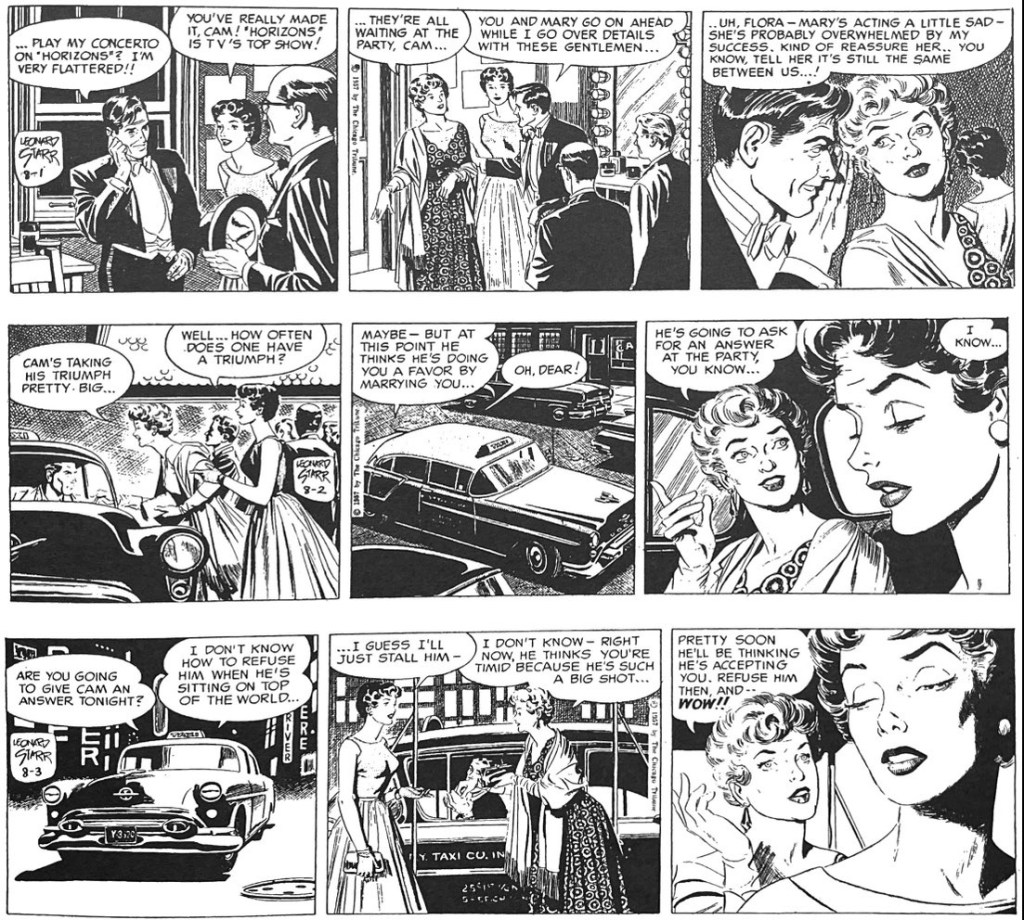

As the photo-realism of adventure advanced in the 1950s, a cadence for using emotional engagement in that three or four panel daily sequence also emerged. Emotive close-ups tended to end the daily strip, as if the traditional cliffhanger or tease panel were being replaced by a note of intimacy or deeper insight into a character. Leonard Starr’s On Stage (later, Mary Perkins On Stage) is the clearest example of this device. His daily sequences often move from medium and long shots to a two-shot kicker in which we either penetrate one character’s feelings or feel a moment of intimate exchange between two people.

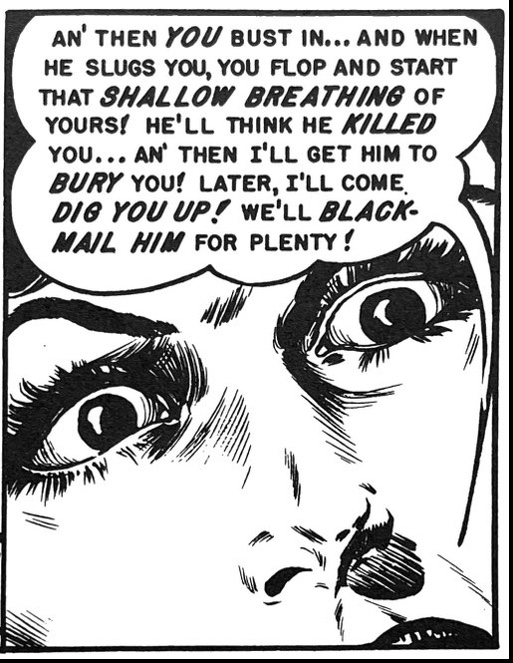

No doubt, comic strip artists were taking some of their cues from the visual tropes emerging from the romance comic explosion of the mid-1940s. Essentially invented by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby in 1947 with the Young Romance launch, the romance genre was immediately and massively successful. As Kirby turned his penchant for physical action inward to emotional landscapes and first-person narratives, he brought the visual perspective in tighter as well. While never a master of facial expressiveness, Kirby increasingly used close-ups and two-shots that tried to evoke, not just illustrate, feeling. Who invented which visual tropes when and where would be hard to prove in the melange of comic book and comic strip changes in the post-war period. One thing we do know about cartoonists is that they pay close attention to one another’s work to hunt new ideas. But it is clear that the visual tropes of facial expression, bringing inner feeling to the surface via close-up and photo-realistic line art, were conventions of romance comics that proliferated across the comic strip page and the evolution of the adventure genre of the 1950s.

And this was part of an inward turn in the adventure genre. Nothing spoke to this shift in adventure more clearly than Alex Raymond’s move from Flash Gordon and Jungle Jim in the 1930s and early 40s to the bespectacled, pipe-smoking, academic detective Rip Kirby after the war. Of course, the wise-cracking, stone-faced manly men of comics lived on in the likes of Steve Canyon and Johnny Hazard, now as small businessmen. But we see a more contemplative, introspective turn in Kirby and especially in Big Ben Bolt. Ostensibly about a champion boxer, John Cullen Murphy quickly filled his hero with self-doubt, a distaste for the violence of the ring and a preference for intrigue and social drama. Similarly, new more institutionally-grounded therapist/heroes like Rex Morgan M.D. and Judge Parker emerge. The early space operas like Twin Earths and Sky Masters of the Space Force celebrated our egghead heroes, scientists working within larger government and corporate structures. The age of The Organization ?Man was upon us.

And yet, the comics were registering an undercurrent to post-war America that would become more important in the next decade, the triumph of therapeutic culture. The 1950s is stereotyped as the decade of bland consumerism, anti-Communist jingoism and enforced conformity. In large measure, the retreat of the action adventure hero into marriage, business, government reflect that tone. Any careful look at high or popular culture of the era tells a much more complex story, howev er. The trauma of WWII carnage, while famously suppressed by many veterans, clearly informed the darker areas of mass culture production. And the Cold War threat of instant annihilation was an undeniable influence throughout American life. Film noir, increasingly grisly crime and horror comics, the proliferation of hard-boiled paperback fiction all suggested that Americans were interested in engaging more conflicted, emotionally taut lives than the more acceptable forms of popular expression portrayed. It was at the sensational, often controversial, fringes of popular culture (like B-movies comics, salacious paperbacks) where we find darker visions of self and society than in mainstream pop culture. And even in the newspaper comics, whose syndication system kept famously conservative and uncontroversial, a new intensity of feeling suggests their artists’ (and audiences’) were interested in mapping our inner worlds.

The psychological dimension of the human animal was also becoming popularized during the post-war period. The field of psychology enjoyed a boost of popular acceptance during WWII, when the military called upon the profession to address soldiers’ trauma. In elite, urban centers, seeking therapy became more common, even stylish. At the EC Comics shop, for instance, both publisher William Gaines and chief script-writer, Al Feldstein, were in therapy. They eventually produced a short-lived comic called Psychoanalysis. But their appreciation for the psychological depth of human character clearly informed their horror and fantasy storytelling. Likewise, the Simon and Kirby shop produced briefly The Secret World of Your Dreams, where “comics meet Dali & Freud,” which was another explicit dive into dream analysis. The legitimation of psychological depth, the role of the irrational and traumatic in social life, was evident across pop culture. Psychological explanations for human behavior surface in everything from “Rebel Without a Cause” to “Psycho.”

1950s popular culture is often caricatured in pop history via the anodyne sitcom in prime time, Father Knows Best, Leave It to Beaver, et. al. But another TV daypart was dominatred by a very different take on suburban America, the soap opera. This was a genre that launched on radio in the early 1930s but proliferated wildly in 1950s television. It is hard to discuss the psychological turn in newspaper comics without seeing its kinship in form and subject to juggernauts like As the World Turns and Guiding Light, among many others. The emotional life of American families had become daily theater. On the comics page, artists like Stan “The Heart of Juliet Jones” Drake, Leonard “On Stage” Starr, and even Alex “Rip Kirby” Raymond were able to turn the soap opera tropes, emotional cliffhangers and signature close-ups, into remarkably engaging visuakl moments.

These connections are central to the project here at PanelsandProse, because they suggest how event the most disposable (literally) of simple popular culture is a voice within a larger cultural conversation about itself.

How and whether mass media express an authentic popular culture has been an open debate among scholars and critics at least since the Frankfurt School informed much of post-WWII media criticism. Are industrialized art forms, which are owned and operated by capitalist elites even capable of voicing genuine resistance to a status quo that clearly benefits this class? That is the perennial problem. I don’t pretend a nuanced conclusion. In a very general way, I have come to see modern mass media as channels for us to both engage and contain the disruptions, anxieties and social tensions we experience around us. As I have argued in several places, the form and content of early 20th Century strips were so appealing because they offered comforting ways of addressing the vague anxieties around modern experience. R.F. Outcault’s Yellow Kid tableaux made the new phenomena of crowds decipherable, manageable. Frederick Opper turned modern machinery, the physics of cause and effect, into pleasant poetry, even a kind of lyrical entropy. Likewise, the domestic strips of the 1920s dramatized emerging dynamics of the nuclear suburban family from many perspectives, perhaps more richly than even the novels and films at the time. We had the sentimentality and gentleness of Gasoline Alley and The Gumps alongside the serious discord of Mr. and Mrs and sardonic Bungles. All at once, and on a single daily page, the American comic strip offered a range of burlesques on the emotional consequences of suburbanizing America. In the Depression era, the failure of political and financial machines as well as a looming European war fueled pop culture fantasies of simpler, organic and even tribal social organizations, even screwball monarchy. And in the post-WWII 1950s, comic strips take a corporate and institutional turn. Everyone gets married – Prince Valiant, Buz Sawyer, Kerry Drake, even Li’l Abner. Adventurers become businessmen and often functionaries of government or multinational conglomerates. Yet at the same time, many genres of comics are turning inward, mapping emotional lives with a new intimacy, a psychological turn. And we haven’t even mentioned the rise of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts during this period, the penultimate contemplative strip. This strip even came with its own kid psychologist.

On the back newspaper pages, we can see American tensions, between institutional and therapeutic values, set either to merge or clash.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Into the Heart of Juliet Jones – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Doctor Porn: Rex Morgan, M.D. Is Here to Help – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Connie and Frank Godwin’s Gentle Realism – Panels & Prose

Pingback: Sophisticated Shadows: The Inner Worlds of Carol Day – Panels & Prose

Love this. Greer

What a fantastic, thought provoking piece. I’ve already argued my defence for the soap opera (and adjacent) comic strips in your post about Rex Morgan (defence is too strong a word, as I think you did give them credit.) But my true heart does lie with the photo-realist entries in the genre, especially Heart of Juliet Jones, Mary Perkins On Stage (granted, we could argue forever if it’s truly a soap opera strip…) and Nick Dallis’ entry into the subgenre, Apartment 3-G (from an interview with artist Alex Kotzky, Dallis picked him specifically to try to compete with Juliet Jones and focus more on the art than he had with Rex Morgan and Judge Parker.) Of course there are some fine short lived examples too–Adam Ames from 1959-1962, written by Juliet Jones’ Elliot Caplin and drawn by Lou Fines being probably the most notable.

In your entry on Juliet Jones you say something I found especially interesting–“these strips both idealize suburban, white, middle class mid-century America and at the same time poke at and disrupt the fantasy.” I realized that it made me think of another love of mine, the “women’s pictures” of that time directed by Douglas Sirk. Now, when Sirk’s films finally started to be deemed worthy of study by film scholars, the attitude was that these films were subversive. That Sirk in the films, particularly through his visuals–the use of close ups, reflections, and other elements of mise-en-scene as well as colour–was poking at and disrupting the view of an ideal American [usually] like that was being sold, even when the films dealt with controversial issues.

This take on Sirk has never fully rested comfortably with me–it seems to suggest that if you get emotionally involved in his films you’re intellectually failing the true sophisticated reading of them. Sirk certainly claimed to be interested only in telling compelling stories. And I suspect that’s also true of Drake, Starr, Kotzky, et al. (Although it does add another layer of interest that these artists, mostly, had experience in advertisement art.) I think at their best, you can enjoy them for the stories, and the characters, but also see them as being, maybe, just a little bit subversive.