We are such suckers for highbrow validation. Sure, we pop culture critics and comics historians talk a good game about bringing serious critical scrutiny to popular arts, our respect for the common culture…yadda, yadda. But our pants moisten whenever the intelligentsia deign to take our favorite arts seriously, or we find some occasional reference or connection between the “high” and “low” culture labels that we claim to disown. Comic strip histories love to gush over Cliff Sterrett’s appropriation of Cubist stylings in Polly and Her Pals. Although his dalliance with cartooning was brief, Lyonel Feininger’s Expressionist turn in the Kin-der-Kids and Wee Willie Winkie loom so large in comics history you would think he was a beloved mainstay of the Sunday pages. In face, he was a fleeting presence. Picasso’s devotion to the Little Jimmy strip suggests somehow that Jimmy Swinnerton was onto something deeper than it seemed. And of course the critical embrace of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat started early, when Gilbert Seldes and e.e. Cummings, among others, primed us to believe the greatest of all comics for its surreal aesthetic and mythopoeic narrative.1 Never mind that the strip suffered limited distribution and perhaps narrower audience appeal. Indeed, an entire scholarly anthology, Comics and Modernism is a recent map of all the ways in which comics studies tries to wrap the “low” comic arts in the (to my mind) ill-fitting coat of high modernism.2

I don’t mean to dismiss these efforts. I am myself a lifelong cultural critic of pop culture, always trying to connect common expression with richer historical, aesthetic or ideological currents. I have spent my life “reading too much into” ephemera. But because I have been at this so long, I have also experienced among several generations of fellow pop culturists a cloying need for cultural legitimization. Call it the pop culture critic’s eternal inferiority complex; for all of our populist talk, we still crave highbrow validation. I would agree with the general premise many of these critics and scholars take – that the comic strip and high modernism both addressed the modern intellectual and social context by playing aesthetically with ideas of time, space, pace, motion, even consciousness in new ways. I would only argue that such an insight doesn’t go far enough and admit that mainstream comics took these qualities in more accessible and populist directions that were decidedly not avant-garde.

The pop culture critic’s fetish around tying popular cartooning to high modernism may be defensible theoretically, but it misses the obvious. There is a more concrete and ultimately more productive connection between comics and the fine arts – the modern American Realism that evolved in parallel to the triumphal rise of the comic strip itself. At just about the time the newspaper comic strip emerged as a native American folk art, so too were some of the nation’s fine artists struggling to find a native American voice for painting. Like The Yellow Kid, Happy Hooligan, Little Nemo in Slumberland, fine American art turned toward chronicling the objects and environments of everyday modern life. Critics often dub this strain of painting broadly as “American Scene,” a nativist representational approach to painting that included The Eight and Ashcan School (1900-1920), budding realists of the 1920s like Edward Hopper, Charles Burchfield and Thomas Hart Benton, and the full-blown nativist strain of the 1930s (Regionalists, Social Realists, folk art revival and public murals). I would also include what we might call the “Narrative Realists” like Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth and the story/book illustrators of the Brandywine School. This diverse set of styles and subject matter shared a common and self-conscious aim of testifying to the range and variety of a distinctly American experience and visual voice. In fact, many of these “American Scene” figures positioned themselves in opposition to the high modernism that seemed to them increasingly abstract, inward-looking, precious, and especially inaccessible and thus undemocratic. And while these American artists had a range of styles, and incorporated aspects of modernist abstraction, Impressionism and Expressionism in their work, they all diverged from European modernism in a key respect. Their devotion to representational styles (a.k.a. realism) was aimed at making art more relevant and accessible to a broader audience. Which is to say that the American Scene tradition is quintessentially American and part of a longer history of American portrait, landscape and genre painting. This American realist tradition always had democratic aims – to depict the material conditions and objects of everyday life, in a style that was understandable to all, and in search of a native national voice. In all of these aspects, I think both the visual styles and aesthetic preoccupations of comic strip art should be understood as part of that larger project in American art.

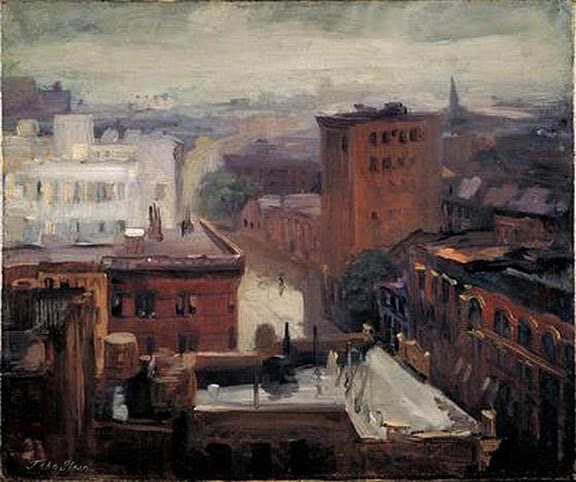

The crossover of American fine artists and the nascent American comic strip are as obvious as they are generally unexplored seriously by historians. “The Eight” sometimes characterized as The Ashcan School or “The Revolutionary Black Gang” all started and even met as newspaper illustrators. They included John Sloan, George Luks, Stuart Davies, William Glackens, Robert Henri, Ernest Lawson, Maurice Prendergrast and Everett Shinn. Most were staff illustrators working on editorial, decorative, news and one-shot humor pieces. But some had their own strips for a time. Luks, of course, took over Hogan’s Alley/The Yellow Kid at The New York World when its originator, R.F. Outcault left to join Hearst’s Journal. John Sloan did a highly regarded (and mystifying) cartoon puzzle series for the Philadelphia Press and Paul Palette, The Practical Paintist (1905), an artist who pranks people with too-real paintings. Pursuing a range of individual styles that absorbed some impressionism and abstraction, they insisted on depicting specific moments of everyday modern existence, the colors of urban landscapes, the dynamism and vigor of the fast-growing city, a sense of reportage. Many of their paitnings remain familiar: Sloan’s “Sunday, Women Drying Their Hair” (1912); Luks’ “Hester Street” (1905); Shinn’s “The Vaudeville Act” (1903); Henri’s “Snow in New York” (1902). While they rejected the aestheticism of European art movements, these renegade Americans also absorbed some of the modernism’s principles: simplicity, honest use of materials, elimination of the extraneous detail. These ideas are similar to the aesthetics of cartooning.

Consider, for instance, the most obvious crossover of painting and comics, George Luks (1867-1933). who lampooned the ethnic neighborhoods of 1906 New York for Joseph Pulitzer in Hogan’s Alley, replacing its creator R.F. Outcault, who had been swiped by William Randolph Hearst. In coming years, Luks created stunning canvasses of New York’s Jewish emigres in one of his most famous Ashcan touchstones, “Hester Street” (1905). In both cartoon and painting, Luks reads the cityscape in its walled, cavernous, airless crowdedness. Likewise he builds the city crowd as clusters of independent action – not a crowd so much as crowdedness. Many Ashcan painters and early newspaper cartoonists pursued a similar cultural project – interpreting the new environment of the big city. Luks, himself the son of immigrants, insisted on the humanity in the throng by showing clusters of people not ignoring but engaging with one another in multiple planes of action. Some are in conversation, others seem to be talking while looking, acting as spectators on the city scene. Each has her or his own expression, attitude, personality. This way of seeing the new reality of early 20th Century urbanization, masses of people, was a critical link between American paitning and cartooning. Luks’ idea of the crowd not as a mass but as an engaged set of clusters, had been well established by his Hogan’s Alley predecessor Outcault.

And Luks suggests in both painting and cartoon a sense of the endlessness of this environment. In “Hester Street,” the deep perspective down the street and into the next crossway suggests that whatever he is highlighting in his foreground just goes on and on in its own way. In “A Snowball Battle in Hogan’s Alley (The World, Dec. 20, 1906), he is carving but a slice of a street that clearly extends beyond each end of the page. Just as important to both images is putting performance at the center of the city scene, the looming snowball and the waving crowd in the cartoon and the toy salesman surrounded by children in the painting. This is an important point that joins the concerns of the Ashcan School and newspaper cartooning – constructing the urban throngs both as crowd to be observed and as themselves spectators on the crowd. The spectacle of the city environment, the performative quality of modern life, was part of the point among both urban realists and cartoonists.

And this is where connecting cartoon history with formal art history can help. In her superb dive into the Ashcan School, Rebecca Zurer argues that these painters were part of “the culture of looking that developed in the early twentieth-century city.” Luks, Sloan and others in this school similarly depicted New Yorkers “looking, peeping, watching, and scrutinizing, of seeing and being seen.” (Zurier, Rebecca. Picturing the City: Urban Vision and the Ashcan School. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006, p. 4). The Ashcan artists were trying to help us experience the new city in a more humanized way, to do what great art always does – give us new modes of seeing. For instance, Zurer contends about the Ashcan artists, “Their view accepts the crowd as knowable and regards strangers with interest rather than apprehension or distaste.” (Zurer, p. 19).

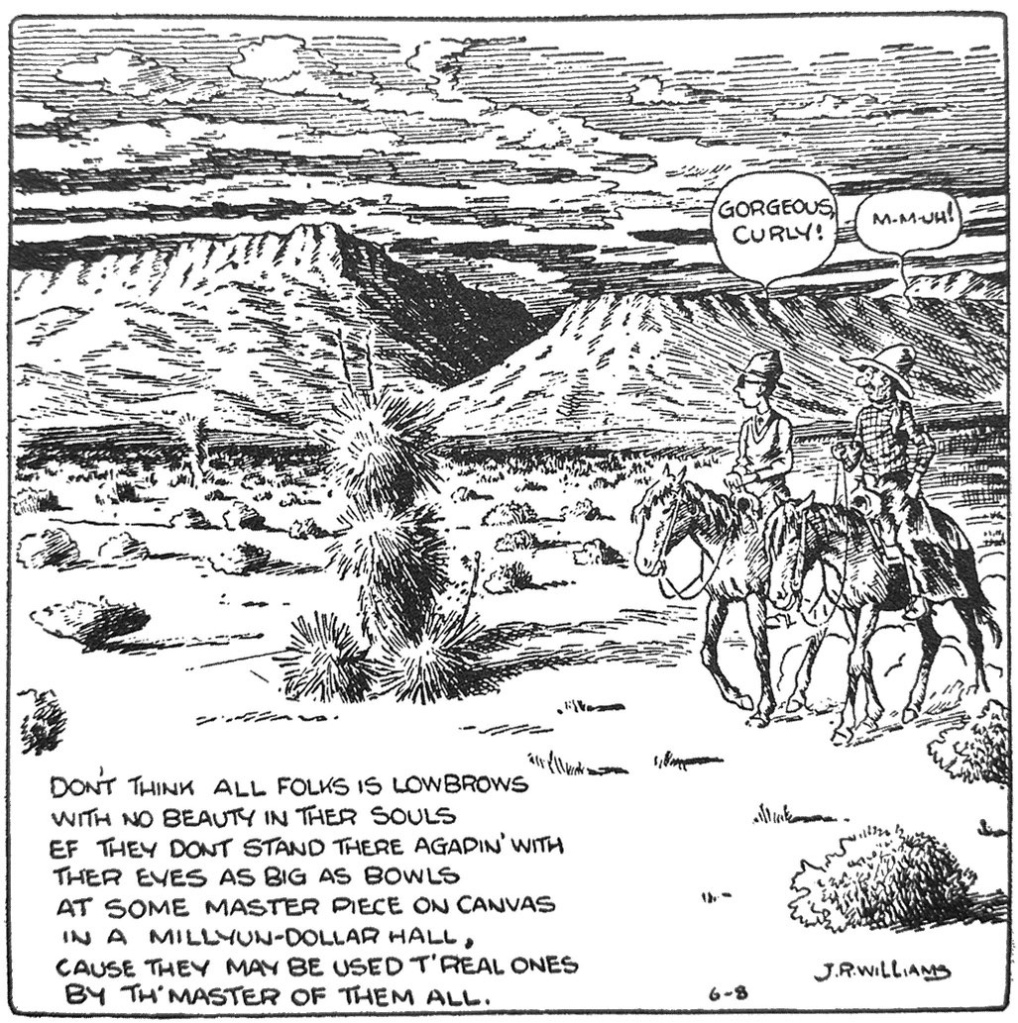

Engaging the ways in which comic strip art is cross-pollenating with an evolving American Realist art tradition opens these artists and strips up to be explored more seriously as landscapes of modern America, visual interpretations of the cityscapes, frontiers, still lifes, farmland, drawing rooms and architectures that preoccupied American Scene painters during the same first four decades of the 20th Century. J.R. Williams is telling us explicitly in the Out Our Way strip above what many American lanscape artists had implied on canvas, that an idea of God was to be found there. But where is that God for Williams here, or in the thousands of other frontier background he drew over decades? To understand what kind of everyday art the comic strip provided Americans in their daily paper, it is a question worth asking. Western cartoonists like Fred “Red Ryder” Harmon made the natural setting virtually a character in his work. Frank King’s Walt Wallet famously took long road trips into rejuvenating nature, and King’s reverence for that experience is expressed in all of the different ways he composed those natural settings. He was telling us what nature meant to him and trying to visualize what it might mean to us. But why wouldn’t we presume he and other cartoonists are treating the interior domestic realm with similar care? Traditional analysis of realist paitning pays close attention to the choices are made in how artists define space, the objects that indicate place, status, the style and values it expresses about the people who live there. What happens when we ask similar questions of Bringing Up Father, The Bungles, Dick Tracy, Moon Mullins? And what if, following in the spirit of Williams’ cartoon, we started looking for a populist aesthetic in newspaper comics?

One of the hallmarks of the Ashcan School was a self-conscious rejection of the genteel propriety of the artistic establishment, namely the National Academy of Design which valorized gentler middle class subjects and shut out many of these upstart illustrator/artists from the shows and competitions that built careers. Many of these younger artists were inspired by the urgings of Philadelpia-based mentor and teacher Robert Henri. He urged these artists to embrace the commonplace objects and scenes that informed working men and women, to find nobility and meaning in small things. in fact, it was Henri who urged them to study caricature and cartooning in the humor magazines in order to understand the power of expression, posture, etc. (Zurer, 183).

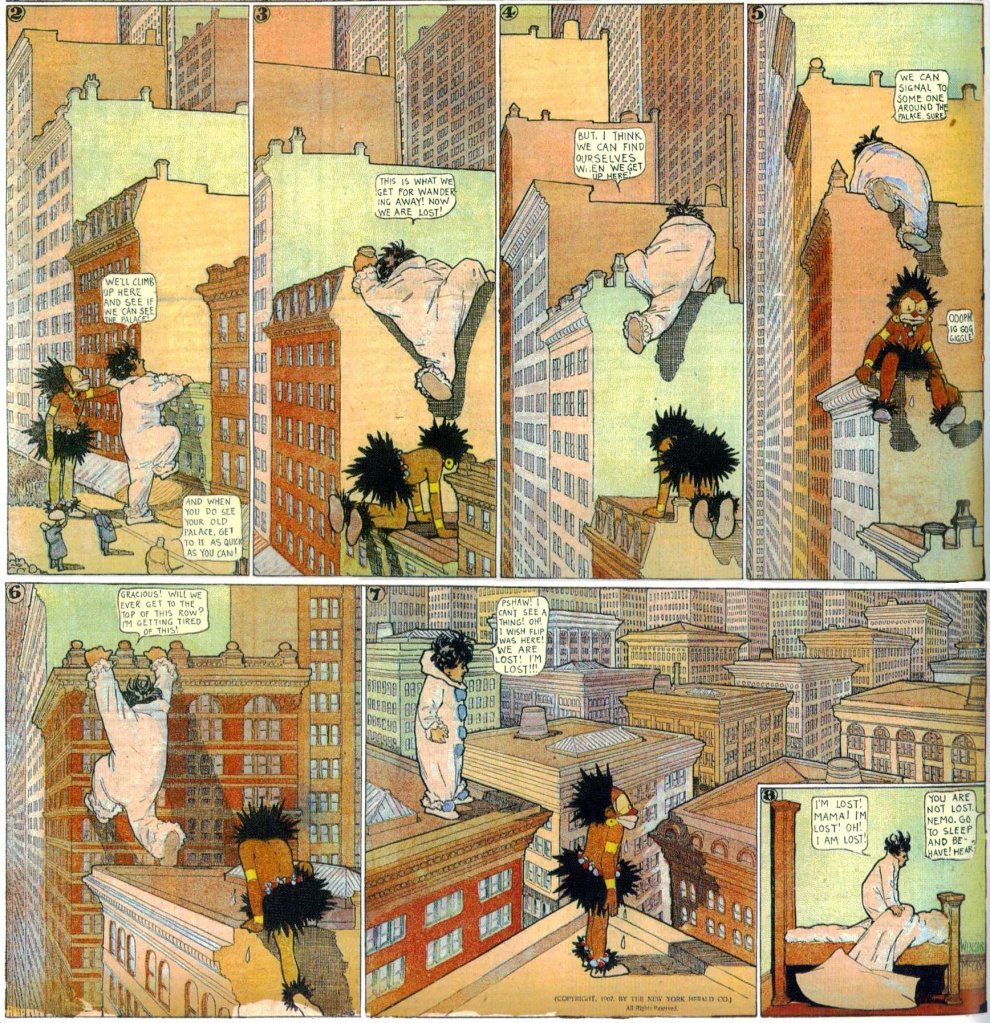

As Zurer notes, cartoons seemed an odd place to find realism. But genteel artists like American Impressionists of the day, only depicted cityscapes that were devoid of people, where the lights and architecture were therapeutically, literally, gauzed over in fog. For an Ashcan leader like John Sloan, the architecture of the new city was part of its expressiveness. Like contemporary newspaper cartoonists Winsor McCay or Walt McDougall he saw in the cityscape what Luks saw in a city crowd – a rich, diverse and human palette of color, shape and style that had its own character. Sloan showed people not just living in blocks of brick but interacting with them, making use of them creatively: hosting pigeons, drying hair on the rooftop sun. In his series of city landscapes like “Sixth Avenue Elevated at Third Street” he raised the point of view often to unnatural heights, creating a privileged position for the viewer.

Arguably, this is precisely how many of the more insightful early newspaper cartoonists presented the new city as a landscape with deep perspective, emphasizing its scale, neat parallel lines, individualized styles within repetitive shapes. Comics historians are fond of romanticizing Winsor McCay’s purported “surrealism” at the expense of recognizing his almost painfully precise attention to architectural detail and symmetry. He used scale, deep perspective and unnatural perspectives to warp the real in endlessly fascinating ways, of course. But at heart, McCay had an almost photo-realist’s respect for rendering the object accurately. Surreal? Yes, often he was. But he bent a reality that was anchored in a modern fetish for technical exactitude. His art echoed the repetitive, symmetrical industrial aesthetic. But like the Ashcan artists, he used the new architecture as an expressive tool. It is not a stretch to argue that the Ashcan School’s rejection of the Academy and American Impressionist views of the city echoed the newspaper cartoon’s rebuke of magazine cartooning. The distance between Charles Dana Gibson’s style, focus, humor and even his depictions of city life and the most polished newspaper cartoons of city life are obvious.

And like these urban realist painters, McCay and other cartoonists addressed audience anxieties about the new city environment by giving them perspectives and tools for mastering it. Sloan, Luks, Glackens and Bellows were making the same moves as McDougall, McCay and Outcault. Raising the perspective on city canyons situated the viewer in a privileged position that turned claustrophobic environments into symmetrical, multi-colored landscapes. Likewise, their art was freezing the crowd in motion to reveal the mass really as clusters of smaller relationships and diverse, expressive faces. It is not just that these painters and cartoonists both took working classes and urban environments at their subjects. It is that they offered viewers the promise of being able to contain, understand, relate to what often seemed chaotic and dehumanizing. In other words, both realist painting and cartooning in the early 20th Century were offering tools for decoding the city.

Zurer tends to distinguish the Ashcan School from cartooning in one important respect, however, ironic distance. It is worth quoting in full.

“Cartoons provided opinionated commentary that constituted a version of real life, while also creating an image of New York for national readers. They proposed their own form of urban visuality by suggesting ways for New Yorkers to regard one another. Presenting city life as amusing rather than perplexing, they depicted strangers as recognizable characters or types whose difference could be seen and read from visual cues. Seeing New York as a cartoonist would require learning to read character from the gestures, costumes, and faces of people observed and then characterizing people that way to others.” (Zurer, 183)

The connections among nineteenth century visual journalism, the Ashcan School and twentieth century comic strips has been mentioned by some comics historians but not yet mined for insights. As early as 1972, noted art historian and critic Albert Boimes wrote in Art Journal that beginning in the mid-1800s, the vast art departments at newspapers were supporting generations of fine artists, from Winslow Homer to Thomas Hart Benton. “Comic strips are in fact the final manifestation of old fashioned illustrated journalism, and their origin is thus related less to technological advances than is generally claimed,” Boimes says. Comics became a channel where these artists got to comment on the minutae of everyday America in a way they could not in their formal painting, including bringing in the verbal vernacular of city diversity. But the relationship between America’s insurgent painters, especially in the new century, and cartooning ran to a deeper philosophical level, he rightly understood. “The relationship of graphic journalism to both the development of the comic strip and the Ash Can School is essentially based on their abiding concerns with the actual quality of American life.”

Even a cursory look across key aspects of these insurgent painters and the visual tropes of early cartooning show them working in parallel. As Zurer wisely observes, Ashcan painters were all about spectatorship, the act (and art) of seeing. In this new urban world of public performance, material abundance and sensory overload, cartoonists and the urban realists used similar techniques of capturing the city as a kind of theatre. Many of these paintings depict urban dwellers watching other urban dwellers. We see this in William Glackens’ 1901 “Hammerstein’s Roof Garden,” which brings us behind the heads of women viewing a rooftop performance. John Sloan’s 1907 vision of passersby stopping to look into the “Hairdresser’s Window” or George Bellow’s famous fight in “Stag at Sharkey’s”(1909) which is as much about the crowd watching the fight, exemplify the Ashcan fixation with spectatorship. They were celebrating the city as spectacle as well as highlighting the performative quality of being in a public square of strangers. And by focusing on the seer seeing in these new performative environments, and by making these cityscaoes seem more decipherable, these painters invited early 20th Century viewers to become more self-aware spectators.

Which is precisely what early cartoonists were doing but in a range of more explicit and burlesqued ways. Decoding a new urban social world of strangers and appearances was the subtext of the first decade of newspaper cartooning. Frederick Opper’s Happy Hooligan was a weekly exercise in misreading visual cues – the ubiquitous policeman mistaking Happy’s good intentions for criminal “anarchism.” Ethnic stereotyping was rife, and not unambiguously derogatory. But so too was the catalog of personality types. From Brad’s Boggs, the Optimist to Charles Kahles’ The Butt-Ins, from Bluffer the Bully, Everett Lowry’s Deacon the Backslider, to T.O. Magill’s Hasty Helen, Opper’s obsessively polite Alphonse and Gaston, to Gus Mager’s Monks menagerie of Groucho, Henpecko, Nervo and Forgetto, early cartoonists fixated on tics, personality types and traits. There was Superstitious Sam, the righteously rageful Everett True, the overly frugal Mrs. Rummage, the procrastinating Peter Putoff, to name just some of the scores of newspaper comics in the medium’s first decade named for personal tics. The preoccupation with social typing among cartoonists cannot be dismissed as lazy superficiality or even mean spirits. It was part of the cultural job – to map the sensations and selves of a new reality modern Americans were feeling.

And to give readers special access to this new world by mapping that reality in pleasing ways. The comic strip developed aesthetic tricks that recruited audiences as uniquely empowered spectators. The tableaux of Outcault (Hogan’s Alley) break the fourth wall from the start of its run, as his Yellow Kid looks at and addresses the audience viewing this spectacle of urban mayhem. This is a device we see standardized in sidekick characters like Gus in Happy Hooligan or Tige in Buster Brown – the wry sidekick telling the audience to “watch this.” Comic strip characters often talk their thoughts, giving the viewer special access to their consciousness.

While in the same spirit, I have gone further than Zurer or Boimes in a number of pieces on Maurice Ketten, Walt McDougall, Dan McCarthy, McCay and Jimmy Swinnerton and R.F. Outcault. Across them I have tried to argue that one of the central appeals of the early comic strip was not only how it helped Americans make sense of the city but how the medium re-presented the underlying forces driving this new urban and modern existence – speed, scale, motion, science, cause and effect.

But the most important through-line between American painting and cartooning in the first 40 years of this century was an embrace of representational art, varieties of realism, to chronicle the people, habits and material reality of modern American existence.

Many of the Ashcan School and The Eight were included in the great Armory Show of 1913, where Cubism and Post-Impressionism made their controversial debut to American audiences. These “high modernist” trends were unmitigated breaks with representational art. But The Eight, along with much of the U.S. public, rejected the aestheticism and abstractions the Armory Show organizers framed as an inevitable “progress” and ‘evolution” of art. The Armory Show made art something to argue about, even on newspaper front pages. But while high modernism clearly did dominate the galleries, the collector class, many artists and academics studying them all throughout the last century, historians should not be so easily cowed. While American illustration, comics, industrial design, and even many American painters domesticated aspects of modernist abstraction into their work, representational (“realist”) styles focused on depicting everyday American experience were the dominant mode in American art. By the time the New Deal arrived in the 1930s to save capitalism from itself, the idea of supporting a native, American art that reinforced a unified national identity seemed downright patriotic.

And the intersection of newspaper illustrators and American fine art painting continued well after the Armory Show and through WWII. Starting with the famous The Eight the comics and modern American Realism had the same roots in illustrated journalism, the chronicling of American life. And that connection continues through the next decades as the next generation of Americanists, the “American Regionalists,” germinated. Thomas Hart Benton’s first gig was as a newspaper cartoonist. Paul Cadmus was a commercial artist. John Steuart Curry spent much of the 1920s illustrating Boy’s Life and western pulps. Reginald Marsh was a prolific cartoonist for The New Yorker throughout his painting career. Radical muralist William Gropper consistently did caricatures for all of the leftist publications across the 1920s-1930s. While many of these illustrators likely saw their fine art work distinct from their commercial work, the connection to illustration was apparent to their detractors – effete critics who snubbed American Scene painters as “graphic artists.”

But let’s glance at some of the ways comparing American Scene painting to comic art might open up our views of comic strip art. Consider the similarities between the most famous boxing painting and Alex Raymond’s early Flash gordon exploration of male bodies clashing. In both the artists ee combat as eccentric almost unnatural movements. The violence is made dance like in its fluidity, frozen at the moments when the fighters dont feel soild and grounded but off balance, maybe most vulnerable. both artists are interpeting violence less as force than as contact, motion, maybe even communication?

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Steve, with the highest level of respect and due appreciation– IMO this was a really chaotic piece, and frankly way, way too much to cram in to a single article, as I perceive it.

Not just in terms of overall length, efficient paragraph-formatting and subject-matter covered, but also in terms of the lack of context in terms of the quoted sections… making for a downright baffling mix of opinion and information, at least for me.

So far across this blog, I find you’ve been downright masterful at arranging and parsing all that kind of thing, which is why I’m truly confused about this latest entry.

In any case, I remain absolutely grateful for this blog, and wish you all the best.

Got your reply in email, Steve, but don’t see it here, for some reason. Possibly an issue with the way my browser permissions are set up.

Anyway, thanks a bunch for explaining that this one was a huge draft covering multiple articles for the future book.

Btw, please do keep posting new stuff to Reddit if it’s not too much trouble. I’m a regular reader there and have given you some feedback there, across the years. You’ve also inspired me on my approach to formatting my articles at my own comics project. Okay, cheers!

Pingback: Tracing The Evolution of Comic Book Artwork: Golden Age to Modern Era Masterpieces – nilmacollectables.com

Pingback: Tracing the Evolution of Comic Book Artwork | Golden Age to Modern Era