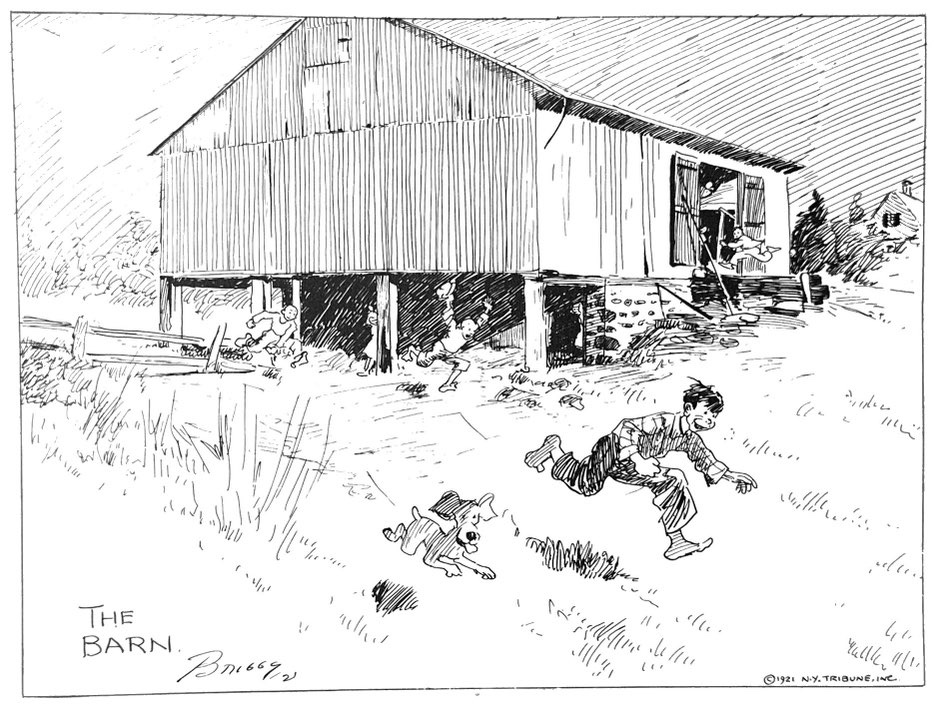

Edward Hopper is best known for the moody isolation of his featured characters. But he was also careful about the objects and architecture that define an interior space. Like many cartoonists of domestic life he relies on iconic objects like the few but indistinct things on the barren dresser, the undersized framed picutre on the wall, the bits of scrolling on the mirror frame. This sparse but ordered interior is designed to heed the things that define space and a life. A characteristic of many comic strip interiors is to define a room with minimal background detail, often white space, sometimes without even demarcating a floor or wall line. But most artists pick one or two iconic elements to render in detail – a lamp, a chair, a sofa, a drape. Many cartoon home backgrounds are are nondescript, of course. The aesthetic restraints of the panel size and the sheer demands of daily production drive many cartoonists towards minimizing background detail. Yet, many artists, like Frank “Moon Mullins” Willard, Chester “Dick Tracy” Gould, or Charles “Ella Cinders” Plumb took considerable care with objects that defined a space. Willard, for instance, built an effective contrast between his googly eyed, big foot comic charcters like Moon and Kayo, a more representational fashionable woman, and living room decor that is carefully symmetrical, overstuffed. There is a vision of the 1920s American home implied here and that we see repeated in a number of other domestic strips. These are all aspects of the modern American suburban landscape cartoonists are building on a daily basis in millions of homes. No museum needed.

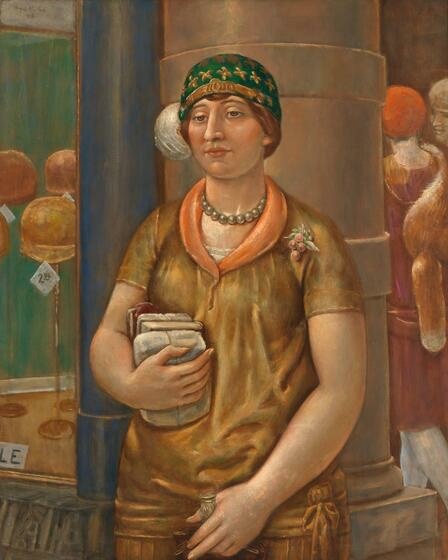

Just as the city was a critical landscape for cartoonists at the turn of the century, it reemerges in the 1930s comics pages as important spaces to define both in gritty crime comics as well as high fantasy. Gould’s Dick Tracy backgrounds are exceptional scene-setters in the small bits of details that eventually become clues or just characterize the material reality of a place. The newsstand image below, for instance, has that horseshoe on a chain in the lower right (to hold down papers against the wind) and the change purse belt on the salesman. Both are details of work life and identity that Gould seems to treasure about his vision of the city.

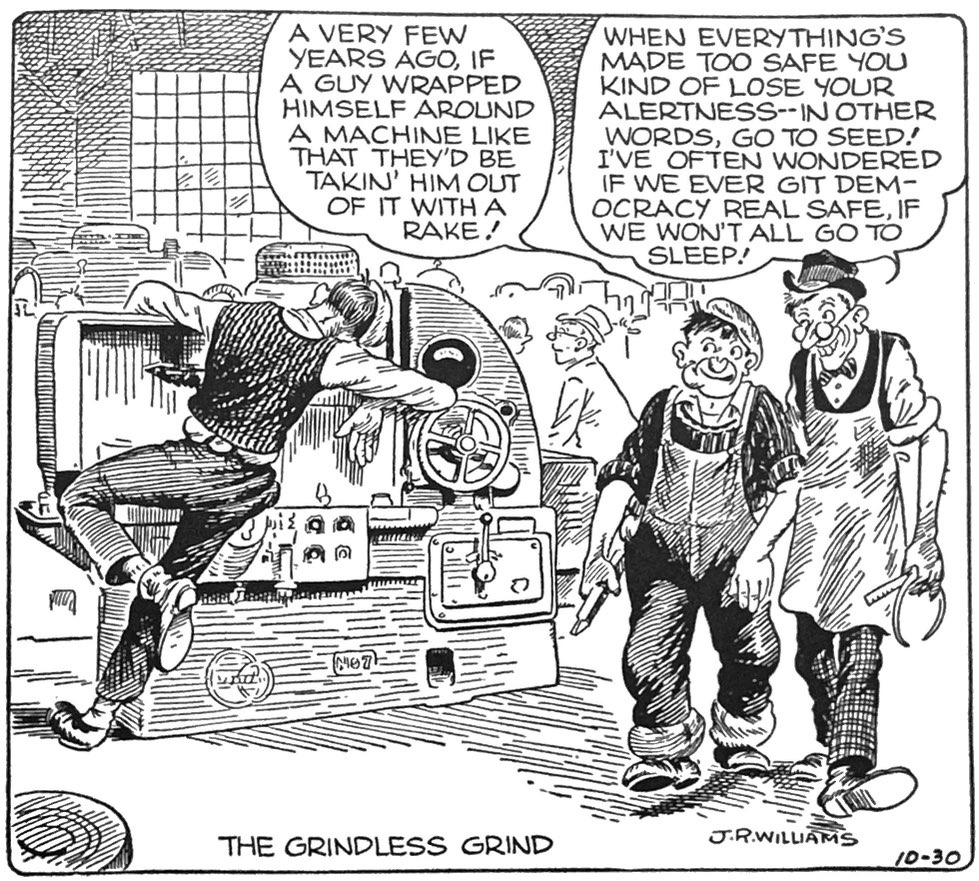

To return to J. R. Williams, he was especially attuned to the importance of visually defining place and its impact on character. His beloved Out Our Way was unique in that it cycled daily through several different worlds: the West of contemporary cowboys, current domestic small towns, and an industrial workshop. It is important to note that this structure expressed Williams’ personal experience. Before landing as a cartoonist, Williams was a journeyman laborer who had gigs as a ranch cowboy and a machine shop worker, among other things. His landscape of the machine shop is just as meticulous as it is for his frontier vistas. The former is an engagement with machine and the latter a relationship with God. The gauges, levers and the man working them are as integral to the meaning of this landscape as the natural structures of the Western mesas are to two pokes on horseback.

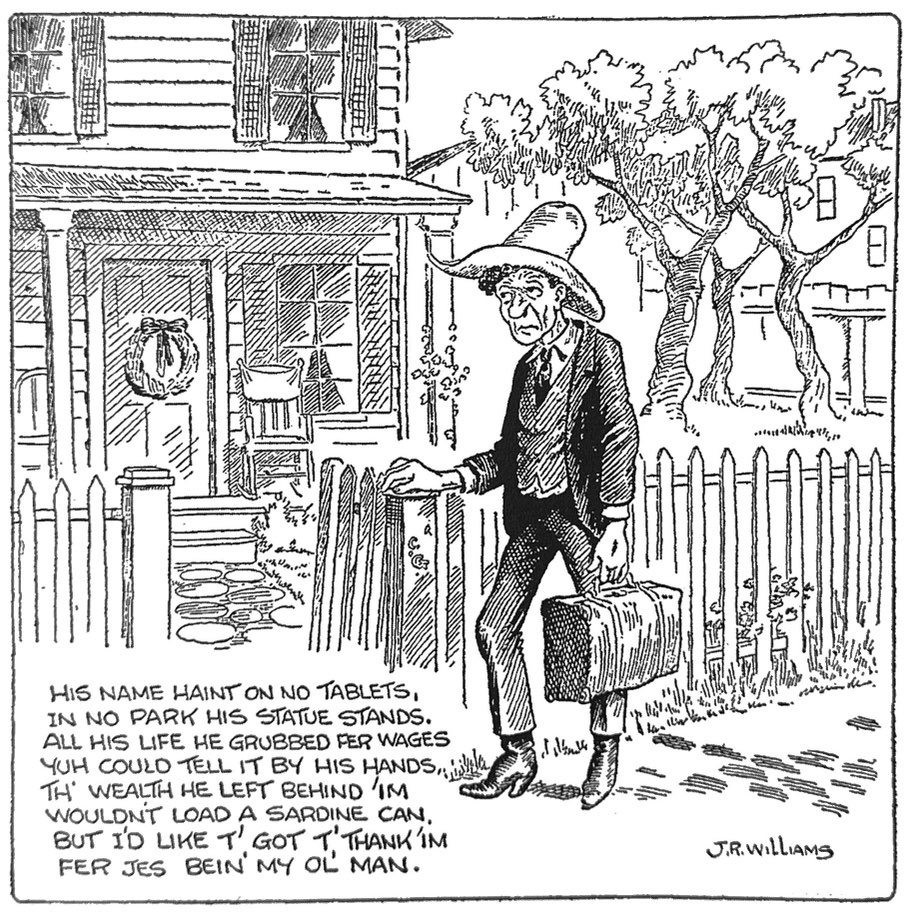

Williams is criminally under appreciated as an American realist. His facility for connecting landscape, architecture, character with larger meanings is remarkable. Perhaps because he has a strong sentimental streak, a quality that critics and scholars use as an excuse to dismiss artists from serious scrutiny, we miss the subtlety. The prose in his peon below to the “old man,” sounds rote and hackneyed. But the image of a work-weary, tired and sunken man entering the pristine, welcoming home and bucolic neighborhood his toil made possible speaks volumes about ideals of masculinity, work, suburbia, sacrifice and compromise, let alone fatherhood.

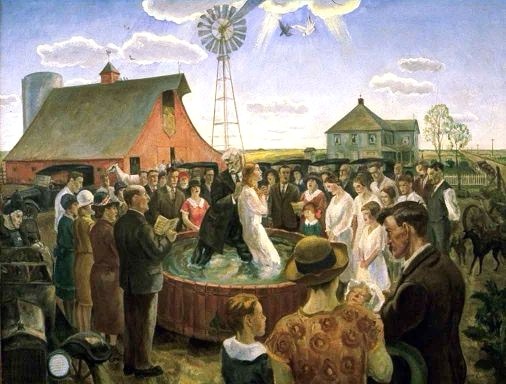

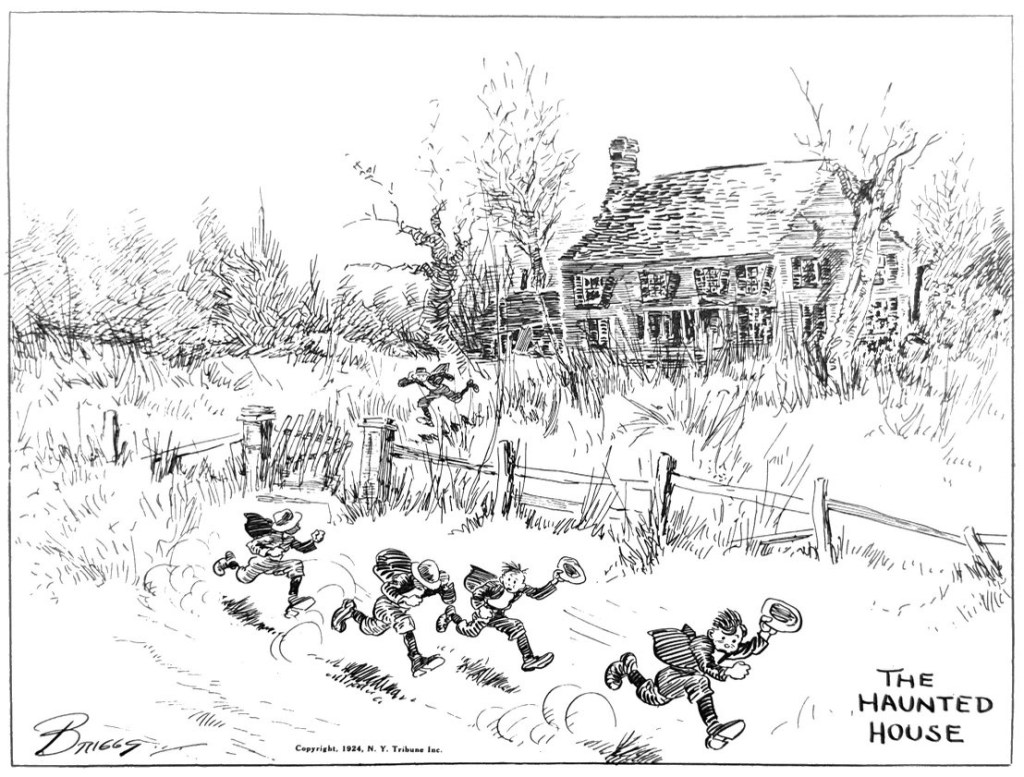

In the interwar period (1919-1939) and especially in the 1930s, landscapes,, both natural and manmade, drew fine art painters and cartoonists equally. One of the major responses to the Great Depression was a glorification of the American folk, back to basics agrarian values, the meaning of the land, a nativist focus on American traditions and finding a distinctly American voice. At the same time, this era was famously dubbed the “Machine Age,” characterized in art, architecture, industrial design by symmetry, sharp lines, streamlined efficiency. These very different responses to modern change were evident in both high art and cartooning. The American Regionalist painters like Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, Charles Burchfield, Reginald Marsh, John Stuart Curry followed the lead of earlier painters like Robert Henri, John Sloan, Edward Hopper in seeking an Americanst response to European modernism. These Regionalists and Social Realists focused on the competing landscapes of the modern farmland and the modernizing city. And they self-consciously aimed varieties of realism at common folk, everyday existence, the small objects that defined work and living. Many examples of this approach is included below. It should not surprise us that many of the American Regionalists echoed the techniques of cartooning: use of bold outlines, flattening perspectives, almost rubbery figures.

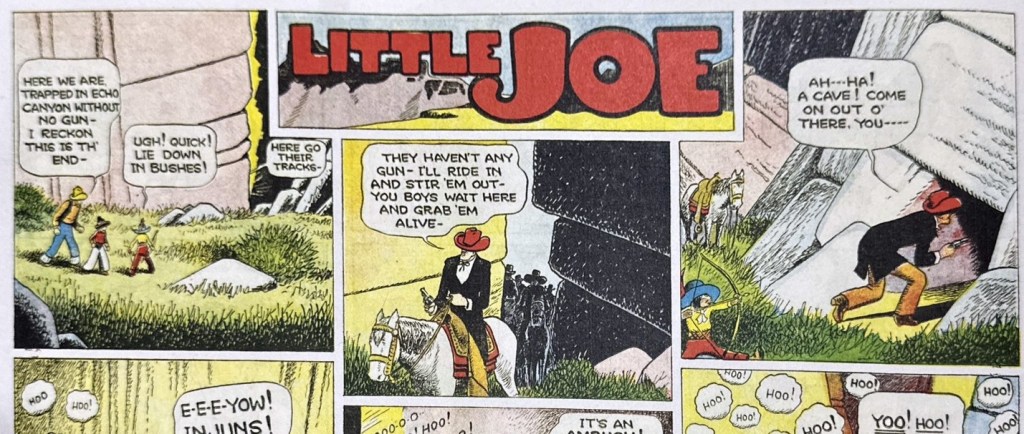

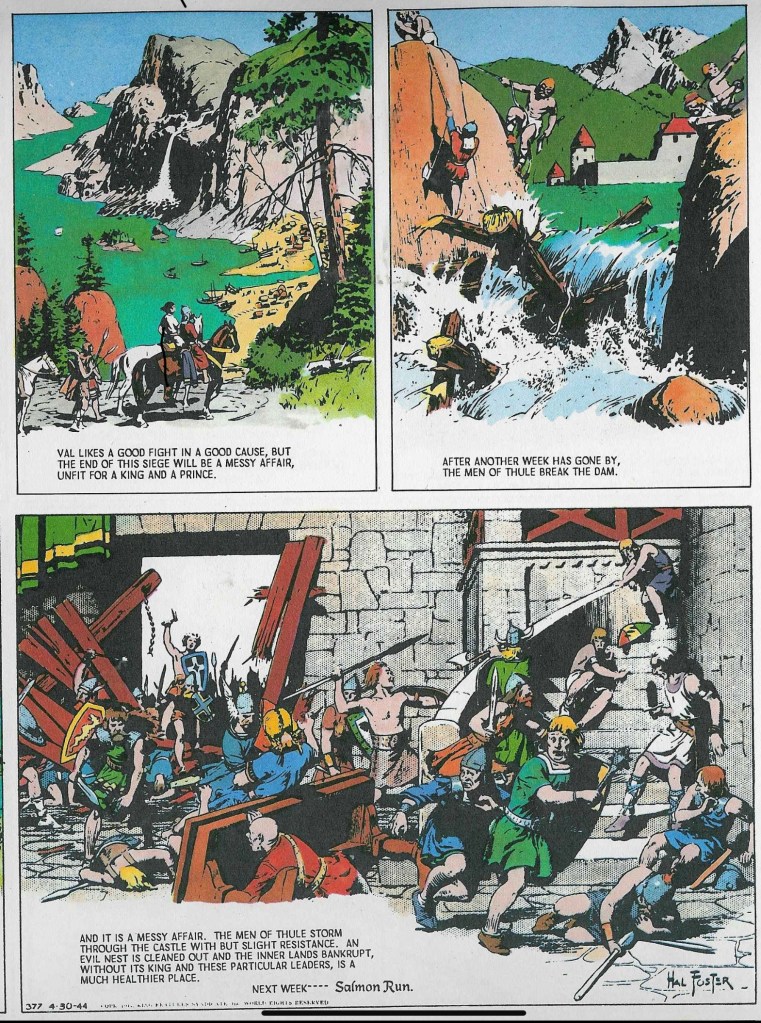

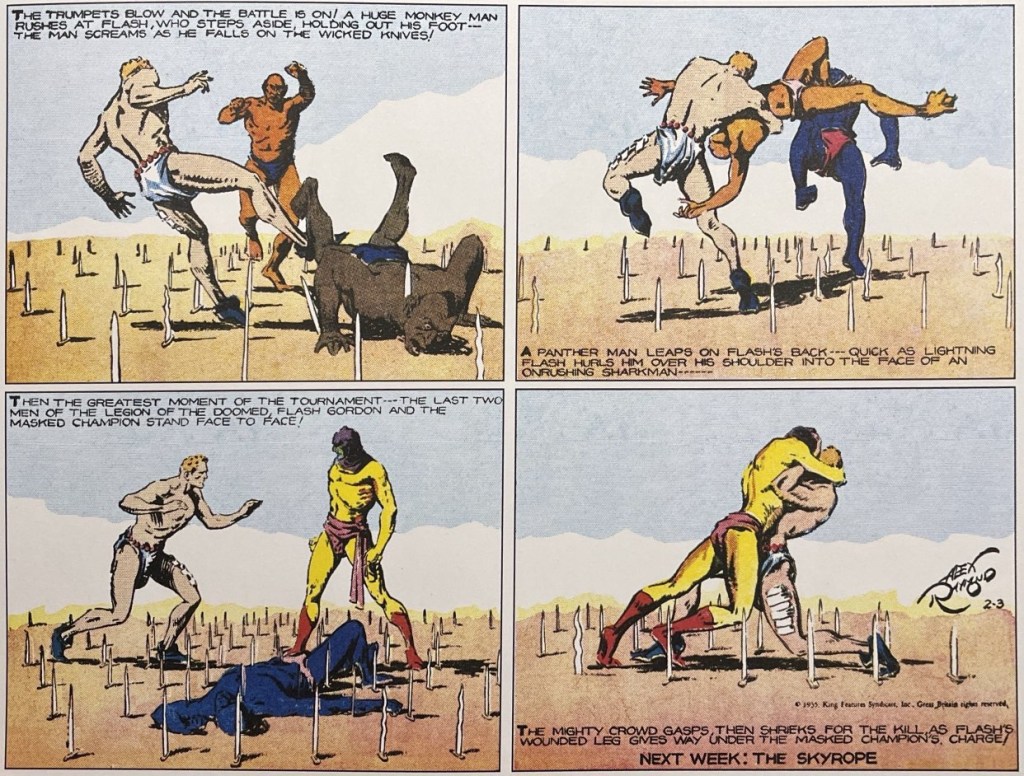

At the same time cartoonists are focusing on these same landscapes. The Western genre emerges in Garrett Price’s gorgeous White Boy, Harold Gray’s art for Little Joe, as well as Fred Harmon’s Bronc Peeler and Red Ryder. But the impulse to define humans in relation to environment during these years extends across space and time. Consider Hal Foster’s vistas of both nature and ancient architecture in Prince Valiant. In Flash Gordon. Alex Raymond was a master of juxtaposing detailed facial expressiveness with landscapes of alien cultures that are defined visually by their architecture.

My point here is that taking more seriously the concrete and spiritual kinship of formal American Realist art and modern cartooning helps us read the comics in even more interesting ways as part of a cultural conversation. As art historian Rebecca Zurer says, cartooning is indeed an odd place to find realism. But it seems to me that understanding U.S. comics as part of a modern American art movement that explored native cultural identity, the meaning of everyday objects and life, and a range of representational styles, deepens our understanding of the true art of comic strips

- On the literary reputation of Krazy Kat, see Aaron Humphrey, ‘The Cult of Krazy Kat : Memory and Recollection in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (2017) 7(1): 8 The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/cg.97 ↩︎

- Najarian, Jonathan. Comics and Modernism: History, Form, and Culture. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 202, As Najarian notes in this valuable volume, there are indeed many “modernisms” in which to understand the comics. And there is no unified academic perspective. Current discussion of 20th century modernism tends to dispense with older discussions of high and low culture and explore the common historical and cultural conditions to which all creative expression is responding (Najarian, p. 7). ↩︎

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Steve, with the highest level of respect and due appreciation– IMO this was a really chaotic piece, and frankly way, way too much to cram in to a single article, as I perceive it.

Not just in terms of overall length, efficient paragraph-formatting and subject-matter covered, but also in terms of the lack of context in terms of the quoted sections… making for a downright baffling mix of opinion and information, at least for me.

So far across this blog, I find you’ve been downright masterful at arranging and parsing all that kind of thing, which is why I’m truly confused about this latest entry.

In any case, I remain absolutely grateful for this blog, and wish you all the best.

Got your reply in email, Steve, but don’t see it here, for some reason. Possibly an issue with the way my browser permissions are set up.

Anyway, thanks a bunch for explaining that this one was a huge draft covering multiple articles for the future book.

Btw, please do keep posting new stuff to Reddit if it’s not too much trouble. I’m a regular reader there and have given you some feedback there, across the years. You’ve also inspired me on my approach to formatting my articles at my own comics project. Okay, cheers!

Pingback: Tracing The Evolution of Comic Book Artwork: Golden Age to Modern Era Masterpieces – nilmacollectables.com

Pingback: Tracing the Evolution of Comic Book Artwork | Golden Age to Modern Era