Across five decades of adulthood, every woman I have ever known was familiar, often intimately, with Cathy Guisewite’s Cathy (1976-2010). Our heroine’s struggles with new and old gender roles, the pressures of fashion and body messaging, diet trends, new tech, workplace culture…and MOM, always MOM, found their way into more diaries, onto more refrigerators and clipped into mother/daughter exchanges than any comic of its day. Tis a pity that so many of us male comics readers passed it over as “not for us” or simply unfunny. Spending a couple of days immersed in the new and most welcome 4-volume Cathy 50th Anniversary Collection ($225, Andrews McMeel) makes clear that Cathy was among the most insightful, witty and intelligent strips we had about the experience of post-counter-culture America. And I could have avoided a lot of stupid missteps with the women in my life if I had paid even glancing attention to Guisewite’s wisdom.

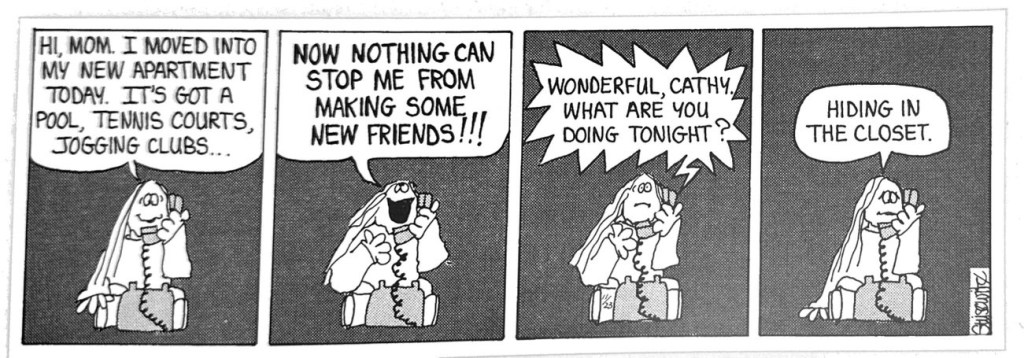

For the uninitiated, Cathy was a perennially single working woman who was relentlessly conflicted about, well, everything. Her supportive but nudgy mother was the voice in her head representing old world propriety and the lure of domestic bliss. Her bestie Andrea soon becomes the married-with-kids friend who lets Cathy witness the road she isn’t traveling. Her boss, Earl Pinkley was an unreconstructed male who piled on the work. Her on and off again boyfriend Irving, whom she eventually marries at strip’s end, seems as befuddled by the changing rules of relationships as Cathy, but he’d rather not talk about it.

Artistically, the strip was among the crudest on the comics page. The massive round heads, rectangular limbs and misshapen objects carried little expressive weight, except perhaps when Cathy freaked out. Then, her explosive, poker straight hair did all of the talking. The basic character design, no nose, scrunched oval eyes, long straw embodied her sunken spirit. The strip looked like the offhand scribblings in a teen diary. Which is exactly what they were, and was essential to the strip’s charm and audience identification.

As Guisewite reflects on the intro to each of the volumes here, the strip was both part of and in response to second-wave feminism and its operative credo that the “personal is political.” The unhappily single Cathy feels yanked among a deep desire for a lasting relationship with a man, the satisfactions of independence and career success, and towing a feminist line. And Guisewite was prescient enough to understand the stifling effects of “political correctness” before we even called it that. “Exactly when a woman’s right to full, triumphant self-expression was being championed, it didn’t feel okay to even whisper that I was somewhere in the middle,” she recalls. Cathy was achingly, hilariously honest about the real personal struggle with cultural change in ways that made ideologues uncomfortable. Ideology is intolerant of nuance, ambivalence, usually even humanity. The strip came under a lot of heat for not being “feminist enough.” And yet it was the most widely read iteration of the “personal is political” insight in any realm of popular culture. Cathy showed the ways in which workplace policies, diet and fashion fads, dating rituals, self-help trends, make-up styles, even product pricing (she was talking about the “pink tax” in the 80s) were about gendered power. And she teased out mixed feelings that were uncomfortable to utter. In a noted 1998 strip Cathy argues with a younger colleague about her leapfrogging a previous generation of pioneering working women. Yet, somehow it still comes down to men. “You took my job and you took a man from my age bracket?” Cathy rages.

The personal is political, but not always in comfortable ways.

The origin story Guisewite tells in this collection is instructive. In the mid-70s she was an up and coming advertising copy writer (in fact the first female VP at the Doner agency) who still sat by the phone waiting for a boyfriend to call. She emptied her ambivalence into a diary, which quickly struck her as repetitive and frustrating until she started visualizing her mixed feelings into scribbled images. She credits her real-life mother with recognizing their potential as a comic strip and researching the syndicates to pitch. Despite Guisewite’s admitted lack of artistic skill or experience with the basics of gag-writing, Universal saw the potential almost immediately and signed Guisewite on in 1976. She resisted the syndicate’s insistence in giving the strip the creator’s own first name, but in this case the suits had it right. Intimacy, painful honesty, self-effacement were all critical elements to readers’ identification with Cathy.

And then there was mom. It was the nuance and complexity of the mother/daughter relationship in this strip that grabbed many readers, because no one in any other popular medium was engaging this deeply persona/political area of women’s lives. Guisewite’s own well-educated and ambitious mom had forsaken a writing career to raise a family. She projected onto her daughter both those unrealized goals as well as the tug of old-school female propriety. Guisewite’s fictional mom was not a mere when-are-you-getting-married nudge. As the creator understood, this was a mom who was supportive, endlessly loving, generous, “who could drive us crazy in four seconds flat.” That nuanced dynamic resonated profoundly with many readers.

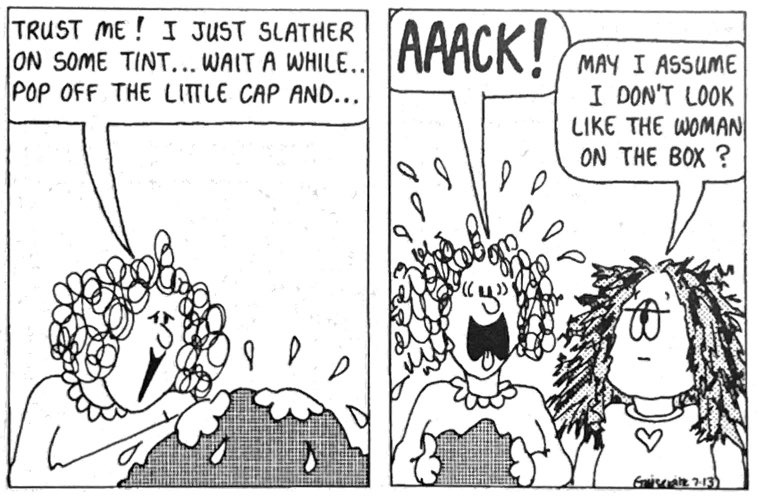

But the Cathy strip also stands as a remarkably perceptive chronicle of how many of us internalized 36 years of American social history. Guisewite curates here 3200 of 12,000 strips she drew across 3+ decades. I won’t cop to having read every one. But some moments really stand out for me. In one extended sequence, Cathy is cajoled into getting a trendy hair perm that leaves her looking like a walking steel wool pad through s couple of weeks of strips. She moves from desperate regret to indifference to resolve to right this wrong, only to find that undoing a perm is worse than a perm. Her weeklong encounter with the quintessential 90s guy is a spot-on send-up of faux self-awareness in “reconstructed” men. Cathy’s internal monologue during a week of hewing to a strict trendy diet is a harrowing descent into self-loathing and indulgence.

As Guisewite makes clear in her intros to each volume, she was immersed in the women’s magazines, self-help books, diet trends, workplace policy debates, tech, movie tropes, fashion and cosmetic edicts coming at us from every direction. And unlike most other comic strips, she named names. There was nothing oblique about this comic’s relationship to its times. Liposuction, the “Computer Christmas of 1986,” Madonna’s “Sex” book, Johnny Carson’s sign-off, numerology and birth order analysis are all here.. She illustrated the trends, called out celebs, political debates, diets, gurus often with the pointed specificity we usually associate with Doonesbury. But she was always willing to show ambivalence about it all in a way that felt real. She was adept at making the political personal and making inner conflict funny.

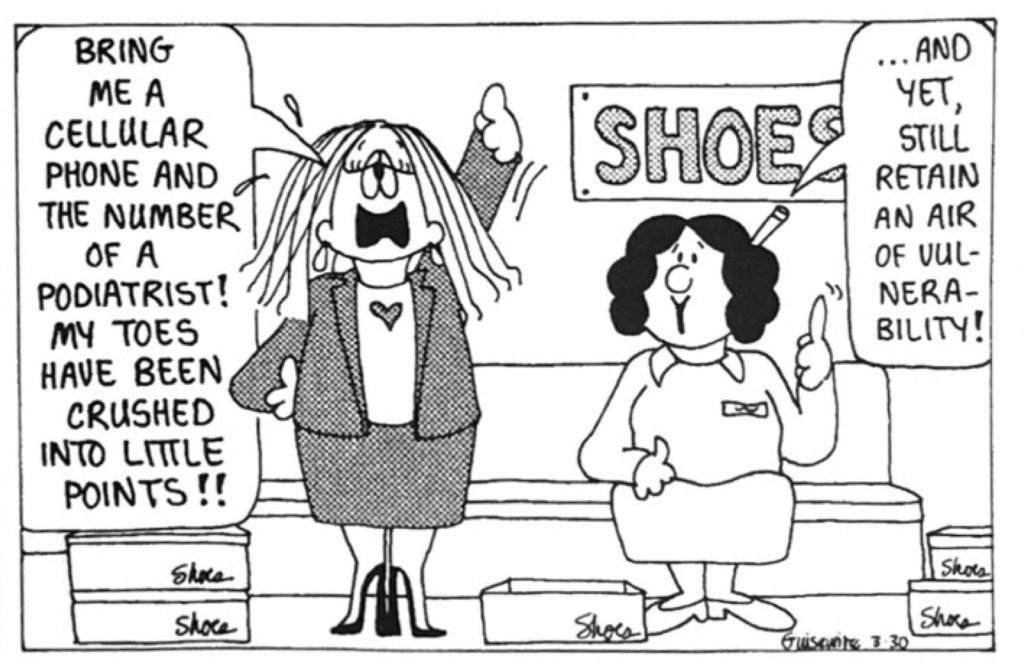

If there was a common enemy in Cathy it was not so much patriarchy as trendiness and consumer culture itself. Guisewite’s sharpest barbs were aimed at the manipulations of marketing to our insecurities. A persistent nemesis across the decades is the unnamed but unctuous salesclerk, the strip’s avatar for American consumerism. Standing beside the dreaded fitting room in what Guisewite calls “the hope and horror of the Swimwear Department,” the clerk rationalizes the latest fashion trends and teases out customers’ insecurities. Cathy shows open self-conscious disdain for a system that exploits her sense of inadequacy, just as much as she upbraids herself for buying into it in the end.

Beyond ideologues who found Cathy too wishy-washy about her own stated principles (aren’t we all?) there are more legitimate criticisms of the strip. Even though the honchos at Universal assured Guisewite that she would overcome her limited artistic skill by producing 365 strips a year, there is little evolution of that over the decades. As charming as the scribble motif may be, it really does limit the expressiveness of the characters. The impact of the content is all declarative because the typical tools of cartoonery – gesture, posture, glance, don’t seem available here. The comic timing and cadence of panel progressions often fall flat as well. There is no thoughtful use of composition to speak of. And too often, the Cathy strip forgets its own strength in making the political/cultural personal. At its worst, Cathy gives us too many anodyne sociological sermons – on silly parenting and fashion trends, on growing serving sizes, etc. Didacticism is usually the enemy of good art. Beyond Cathy and her mother, most of the other characters are used to make declarations rather than reveal parts of themselves. As a result, the strip never creates a world and rich population of its own.

Which is fine. Let’s not make the same mistake with the Cathy strip that world makes with Cathy – expecting her to “have it all.” What Guisewite did do so successfully was find a comfortable but insightful way to talk about aspects of modern existence no one else was addressing regarding gender, relationships, work roles, family. But there was something even deeper going on here. Guisewite created a heroine of modern times who is suspended not only between old and new values but among countless voices in her head. Cathy is the American citizen as consumer, a radio receiver for endless cultural messages about what is right, wrong, fashionable, good and bad for you. She was the right comic hero for the neo-liberal age when we decided as a culture to conflate meaning and value with market forces and commodities. Supposedly new values and ideals, gender identities, changing attitudes, etc. were now being sold to us off the rack and subject to change next season. This year you are a self-confident business professional who is no longer afraid to express your sexuality, because somehow we are more enlightened now. And by the way, we have just the right blouse for that. This collection and its 36 year jaunt through American culture’s greatest product – bullshit – demonstrates just how commoditized and disposable ideas and values have become.

Cathy was at once bemused, repulsed, cowed and enticed by it all – both critical and complicit. The best the modern citizen/consumer can hope to do, this strip suggested, was try to filter signal from noise, try to put up a good ironic front against the marketing rationalizations and our own self-delusions. And by the way, we have just the right shoes to go with that look.

This oversized boxed set of paperbacks can be unwieldy. Paperbound 9×11 volumes do flop around quite a bit, and the box itself is not the sturdiest. Mine cracked along the top in shipping. Nevertheless, the print and reproduction quality are up to Andrews McMeel’s high standards. Each volume selects from roughly 7-10 years of strips, with more than enough space to include full episodic arcs. Both daily runs and a good number of color Sundays are included.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

If you want a deep, deep dive into appreciation for Cathy, I can’t recommend Jamie Loftus’s Aack Cast enough:

https://www.iheart.com/podcast/1119-aack-cast-by-jamie-loftus-83922273/

Thanks for the referral. I will check it out.

Pingback: 2025 Comic Reprints: Rediscovering Lost Classics – Panels & Prose