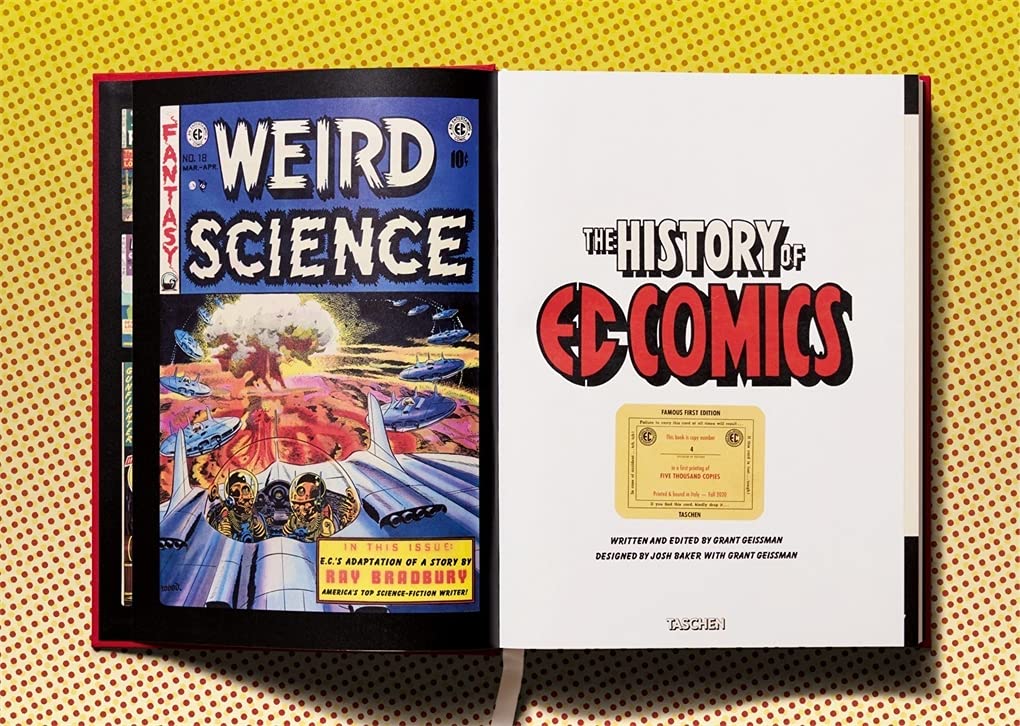

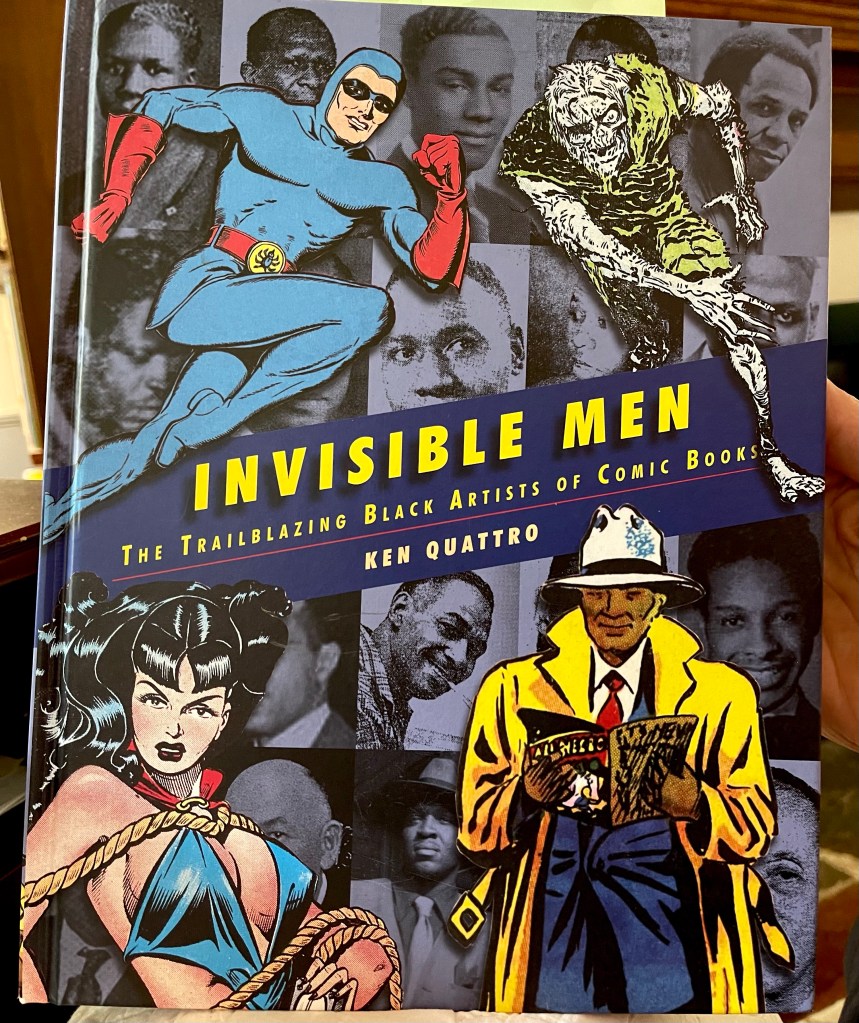

Invisible Men: The Trailblazing Black Artists of the Comic Book

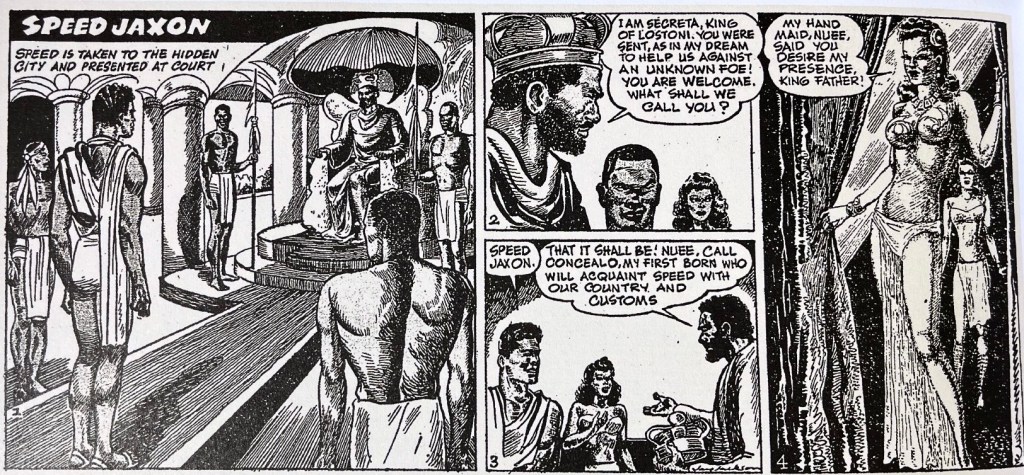

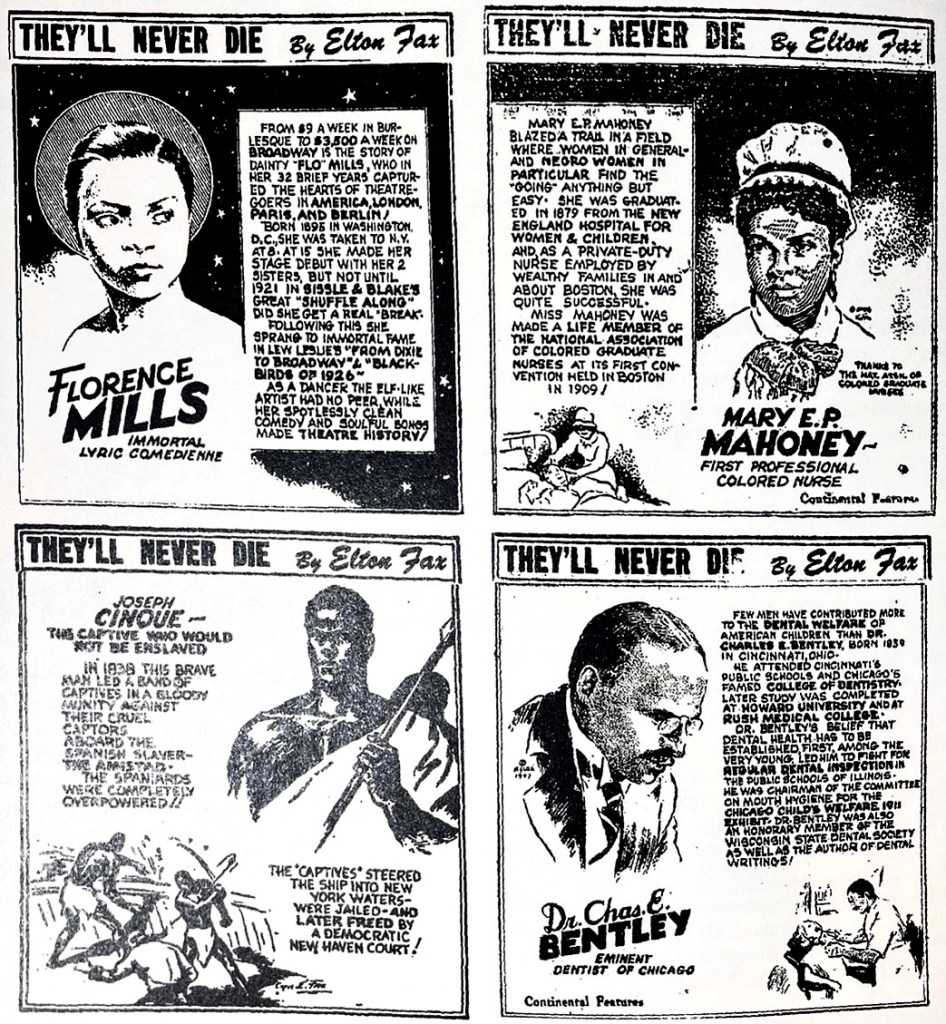

This well produced overview of over a dozen pioneering Black comics artists surfaces a hidden history that is eye-opening on so many levels. Many of these artists were well-known within their own communities and Black newspapers in many of the major cities across the US but “invisible” to the larger world of comics readers. Mainstream comics history often highlights Matt Baker who developed sexy heroines like Phantom Lady and Flamingo and is well represented here. But author Ken Quattro does an excellent job taking a biographical approach that digs into Adolph Barreaux (Sally the Sleuth), Elmer Stoner ( Phantasmo), John Paul Jackson (Tisha Minga and Bungleton Green), the collaborations of Elton Flay Fax and George Dewey Lipscomb, Alvin Hollingsworth’s horror comics, and a dozen more that differentiates the styles, personalities and career paths of an incredibly diverse group of artists.

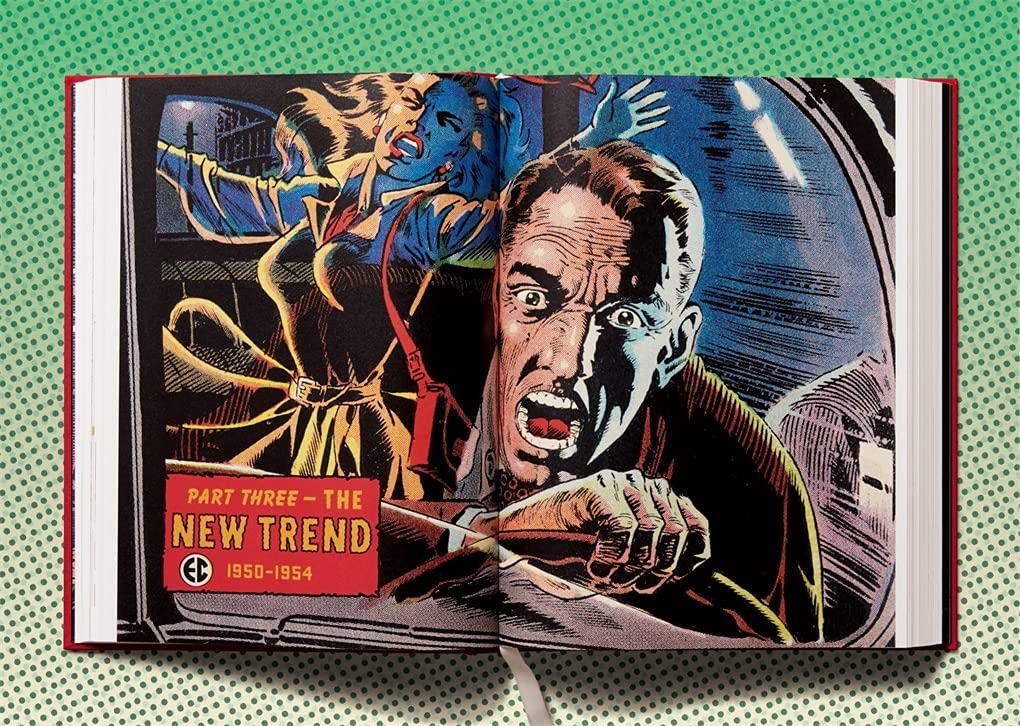

Invisible Men tends to focus on these artists’ eventual contributions to the mainstream comic book field, and so each biographical section usually ends with a full story, full color reprint. Ironically, this work often represents the least expressive and talented examples of what many of these artists had to offer. Their careers generally were more interesting outside of a comic book industry that paid poorly and demanded little. In fact, as Quattro himself recognizes, unlike most early comic book artists, almost all of the Black artists he explores were formally trained fine artists who took on this work just for the money.

In each of these biographies I found their supporting and prior careers much more interesting, as does the author. Quattro cautions that he is not a formal historian, but he ably sketches in a blind spot for comic strip history – the Black newspaper, as well as the vagaries of freelancing for early comic book and pulp magazine companies and how it allowed many of these “invisible men” sustained careers. In taking a biographical approach to this cast, Quattro defies generalization about these artists’ perspectives and backgrounds. We enter a range of highly individual contexts, especially Black middle-class enclaves in cities like Oberlin, Charleston, Baltimore and more. We get glimpses of how Black newspapers, communities, artist groups lent support and connections for many of these men as they cobbled together artistic careers that moved across Black newspaper comics and editorial, community pamphlets, posters and fine art exhibits in addition to the burgeoning comic book industry.

Valuable as Invisible Men may be, it begs for more…more history of Black artist communities, of the Black newspapers that nurtured so much talent, of artists that fall outside of Quattro’s comic book lens. We need at long last a modern report in of strips like Bungleton Green, the syndicates that distributed Black comics artists, an entire history of editorial cartoons that took a decidedly different take on current events.