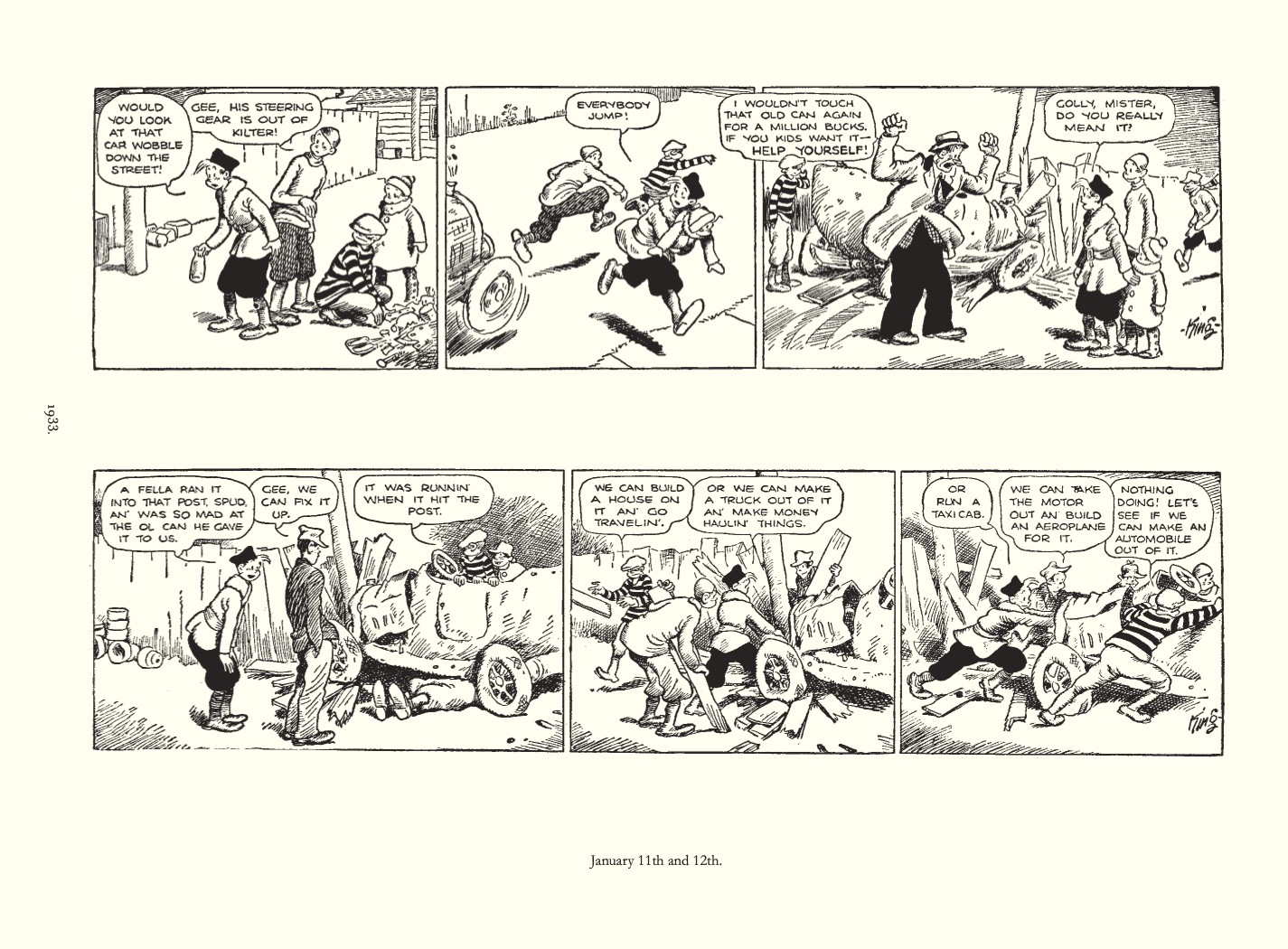

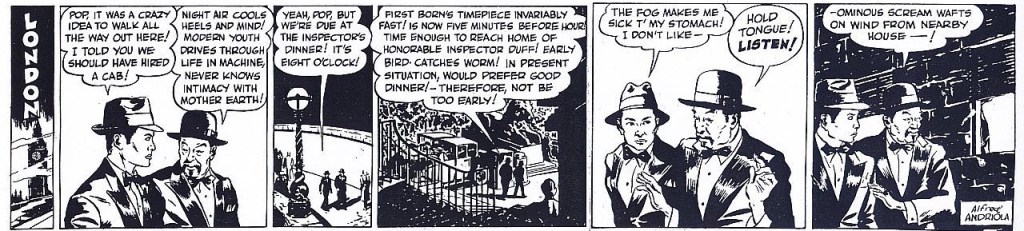

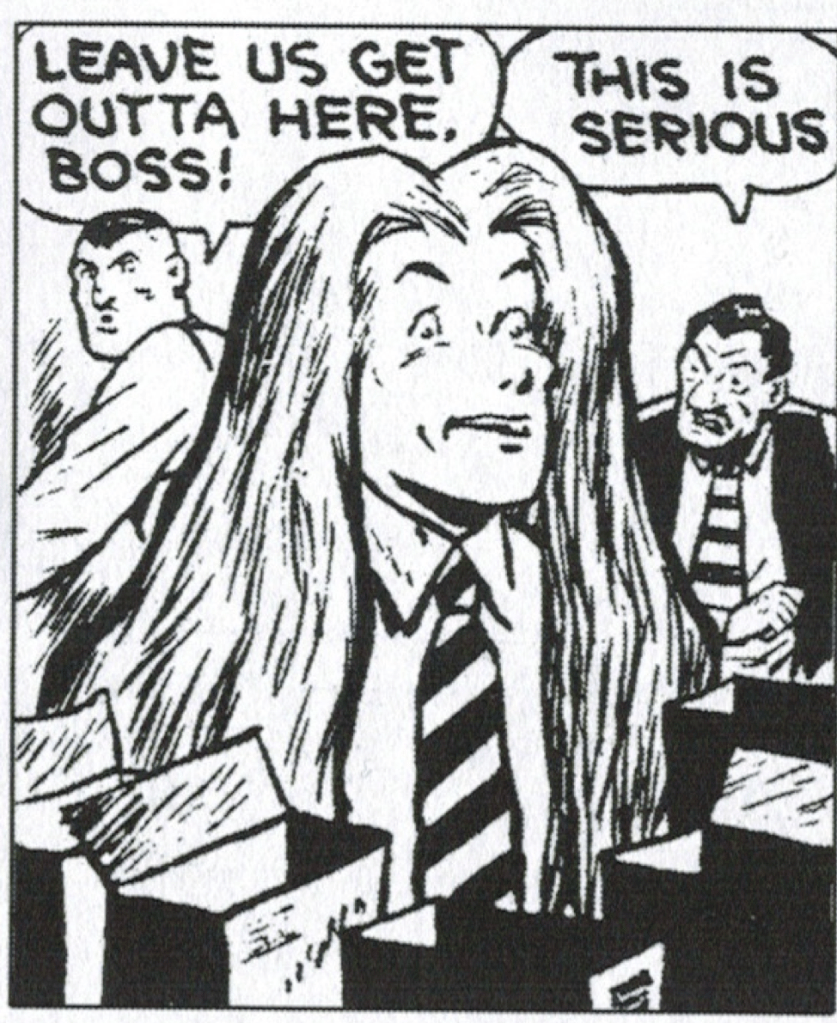

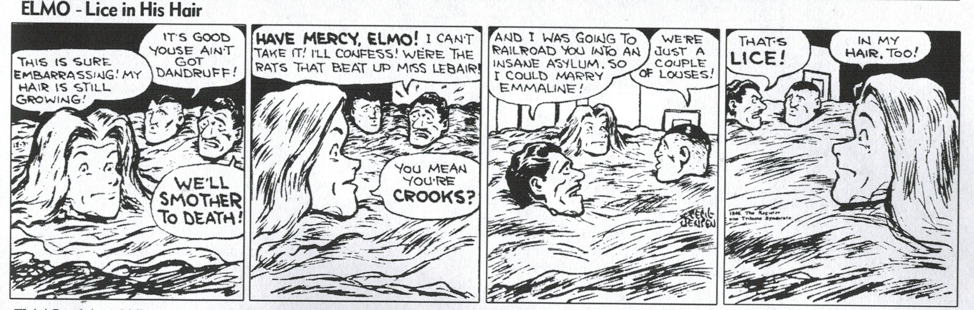

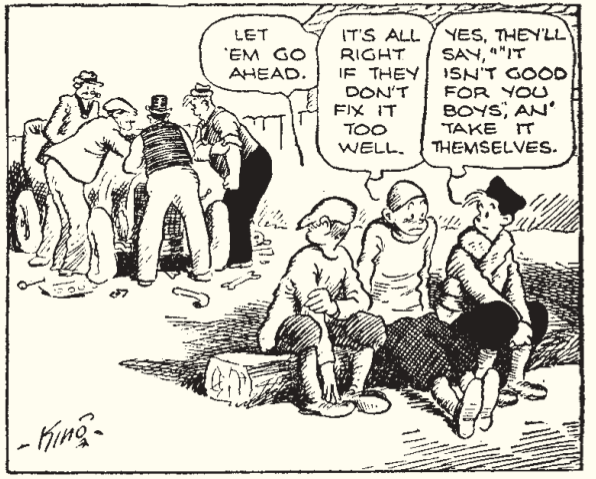

#5 Walt and Skeezix 1933-1934, Frank King, Drawn and Quarterly. $49.99

The sheer everyday-ness of Frank King’s Walt and his adopted son Skeezix is a marvel. For decades Gasoline Alley honored small town life and unremarkable middle-class Americans by making their small dramas, conflicts and schemes important to us. King respected his characters and the reality of their lives so much he did what few other comic strip artists have ever done; he let them age, pass on and birth new generations to replace them. In this volume the Great Depression hits but not that you can tell. The more important development is Skeezix coming into his teens with all the attendant drama. Along with the Andy Hardy films and later Archie comics, we are witnessing here the invention of the teenager as a new cultural type. Drawn & Quarterly, with Chris Ware leading the design of this series, makes each volume even more visually rich and loaded with contextual history. Jeet Heer, the most historically knowledganle comic strip critic we have, provides great background here in the 30s, cultural change and King’s response. If you aren’t collecting the full series, this is a great pivotal volume to get for its glimpse into the maturing characters.