Comic strip history fans should run, not walk, to grab the one indispensable reprint project of this holiday book season, Trina Robbins and Pete Maresca’s Dauntless Dames: High-Heeled Heroes of the Comics (Fantagraphics/Sunday Press, $100). And I don’t mean “indispensable” as a blurb-able critical throwaway, either. The female characters and creators reprinted here from the 1930s and 40s have been “dispensable” in too many histories of the newspaper comic. The central value of this volume is the smart editorial decision Trina and Peter have made here: surfacing strips and artists who have been underserved by the standard anthologies and reprint series. Whether it is Frank Godwin’s pioneering adventuress Connie or Neysa McMein and Alicia Patterson’s Deathless Deer, Bob Oksner and Jerry Albert’s Miss Cairo Jones or Jackie Ormes’ Torchy Brown Heartbeats, the editors have not only featured previously un-reprinted and forgotten material. We get here substantial continuities from each strip that allows a much deeper appreciation for each strip’s character interactions and story arcs than we get from typical anthology samples. You are in the hands of two masters here. Trina has single-handedly championed the history of women comics creators in a number of previous historical and reprint works. And the longtime editor and founder of The Sunday Press, Peter is not only a walking library of comic strip history, but a sensitive curator and restorer. As a book, Dauntless Dames has the same qualities as the heroines it reprints: at once brainy and drop dead gorgeous.

Continue readingTag Archives: 1930s

Mandrake in Dimension Bonkers

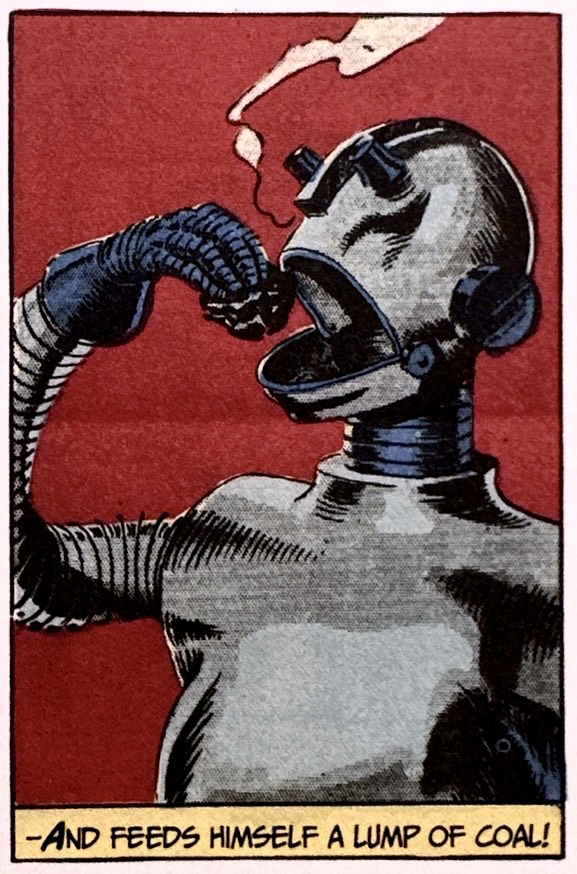

Between August 1936 and March 1937, Mandrake the Magician and his right-hand man Lothar teleported into one of author Lee Falk’s most wildly imagined worlds, Dimension X. It was a universe of altered physics and futuristic super-beings: robotic “Metal Men” made of “animated metal”; “plant people”; ignited, swooping firebirds; man-eating plants; pacifist “Plant People”; and ruthlessly cruel “Crystal Men” who use the skin of captured men to keep their bodies shiny and ready to refract light. Ew! And, of course, no dystopia is complete without hordes of enslaved humans who dream of liberation. It was bonkers, even for a strip that had weird implausibility baked in. And while Mandrake’s side-quest into Dimension X seems like the most fanciful escapism, it was very much of its time.

Continue reading

Campbell’s Cuties: Wartime Women Had Their Moment

The role of WWII in the history of women, equality and feminism in America is widely known and usually mythologized in Rosie the Riveter tales. With many men abroad, women filled roles in industry and management that typically had been denied them. According to the thumbnail version, newly empowered women suffered a kind of cultural whiplash with the post-war return of men to the States. Industry, government and pop culture generally actively discouraged women from enjoying their newfound role outside of the home in range of unseemly ways.

Continue readingRoy Crane: Shades of Genius

Roy Crane doesn’t seem to garner the kind of reverence held for fellow adventurists like Milton Caniff and Alex Raymond, even though he pioneered the genre in Wash Tubbs and Capt. Easy. Perhaps it is that he lacks their sobriety. After all, Crane evolved the first globe-trotting comic strip adventure out of a gag strip about the big-footed, pie-eyed and bumbling Tubbs. But when he sent Wash on treasure hunts and international treks into exotic pre-modern cultures he kept one foot in cartoonishness style and the other in well-researched, precisely rendered settings, action and suspense. It was a light realism, with clean lines, softly outlined figures, often set in much more realistic panoramic backgrounds. This was not the photo-realist dry-brushing and feathering of Raymond, nor the brooding chiaroscuro of Caniff.

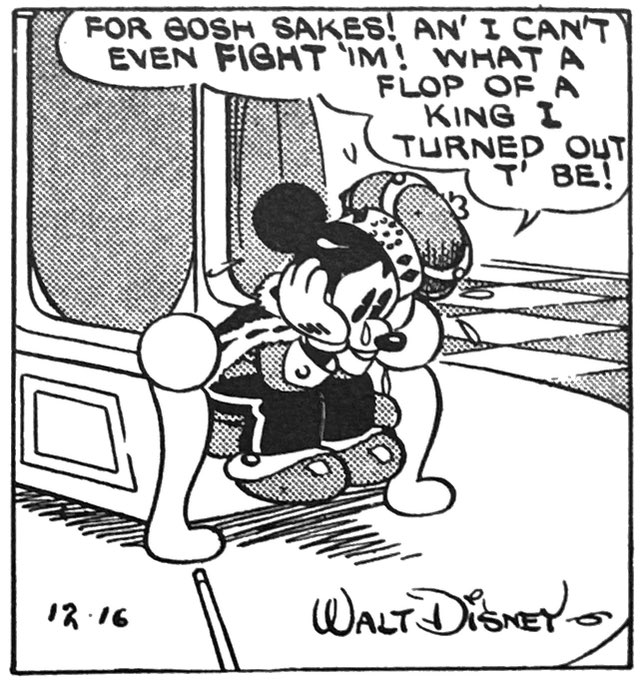

Continue readingRoyal Fetish: Screwball Monarchy in 30s Cartooning

American popular culture took a number of odd turns in response to the trauma of the Great Depression in the 1930s. A fascination with pre-modern civilization, lost ancient worlds, aboriginal tribalism was one of the most pronounced that fueled comic strip fantasy. From Tarzan and Jungle Jim, to The Phantom, Prince Valiant and even Terry and the Pirates, Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy and Flash Gordon, the connection is obvious. At a time when most contemporary institutions were failing, Americans were understandably fixated on pre-modern, anti-modern, prehistoric and fable-like alternative worlds. One of the oddest subsets to this pop anti-modernism was the motif of fantasy monarchy, especially as a setting for comedy and satire.

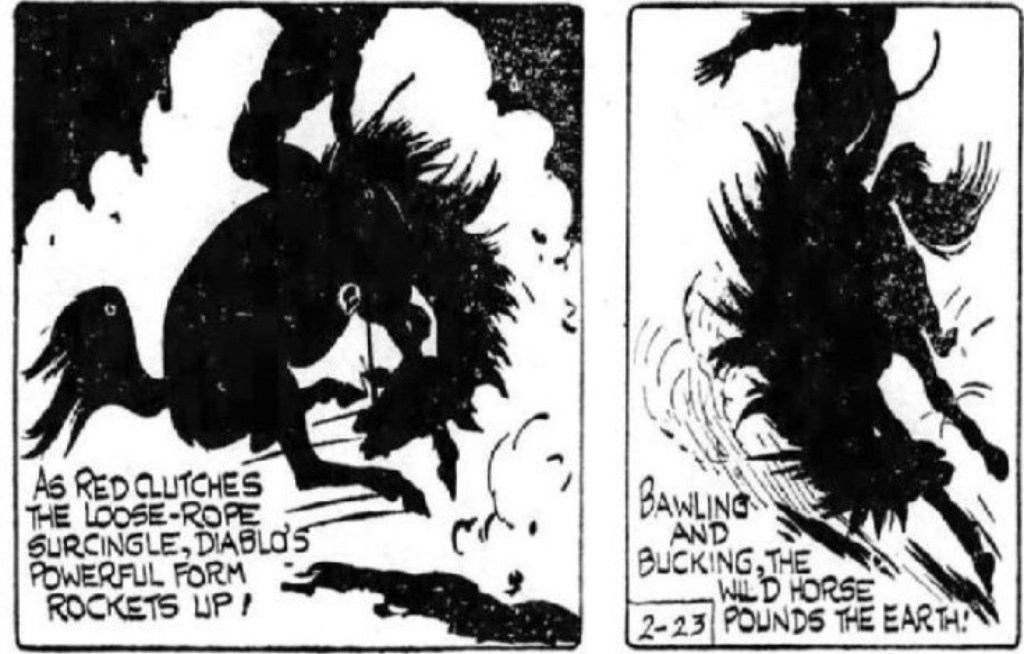

Continue readingRed Ryder: Fred Harman’s Scenic Route

One of the longest-lived and popular Western series of the last century, Red Ryder (1938-1965) is barely remembered today…mostly for good reason. Unlike richer, historically-informed efforts like Warren Tufts’ masterful Casey Ruggles and Lance, Red Ryder was closer to Western genre boilerplate, The titular hero is a red-headed journeyman cowpoke who finds and resolves trouble wherever he roams. His woefully typecast sidekick “Little Beaver” was an orphaned Native American boy who provided identification for kid readers, a sounding board for the solitary and stoic Red, and comic relief of a distinctly stereotyped sort. In truth the strip made little effort to delve into character let alone suspense or high adventure.

Continue readingCaniff’s Art of the Recap Striptease

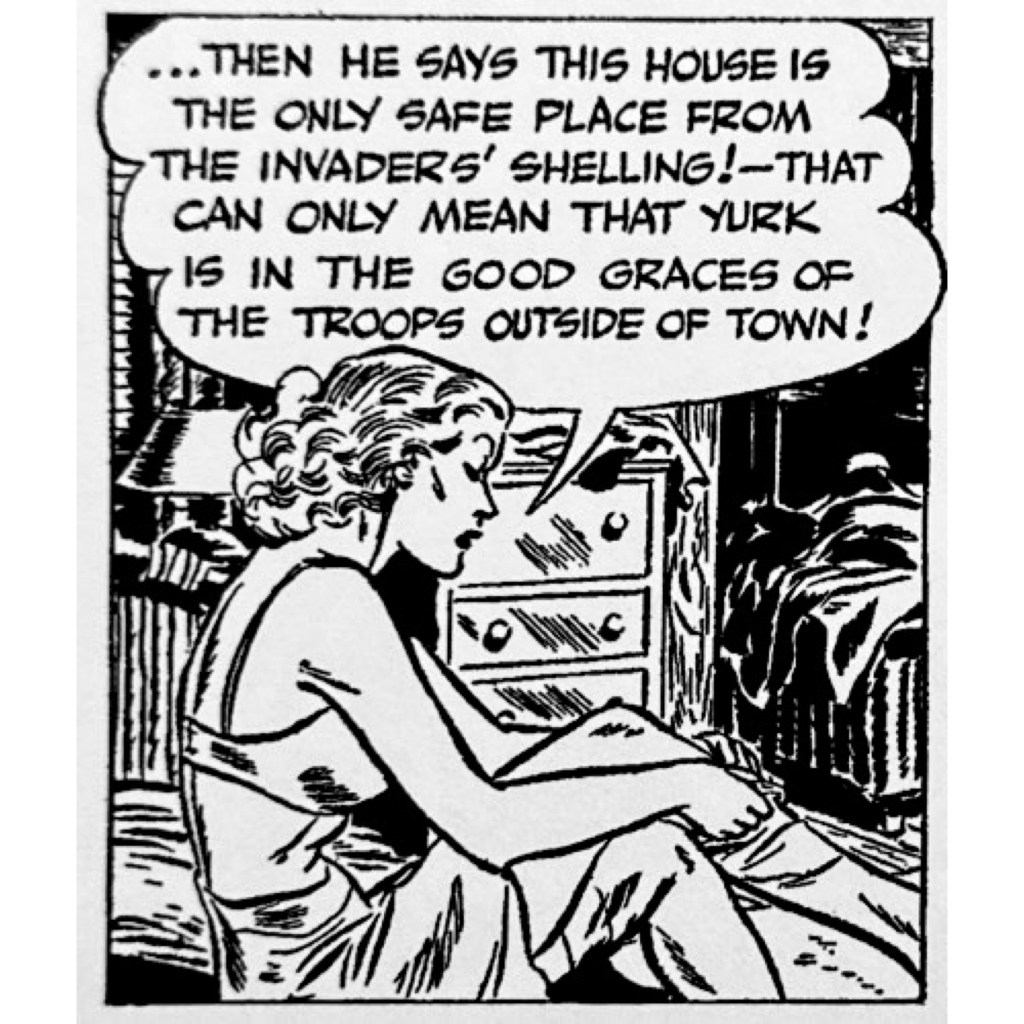

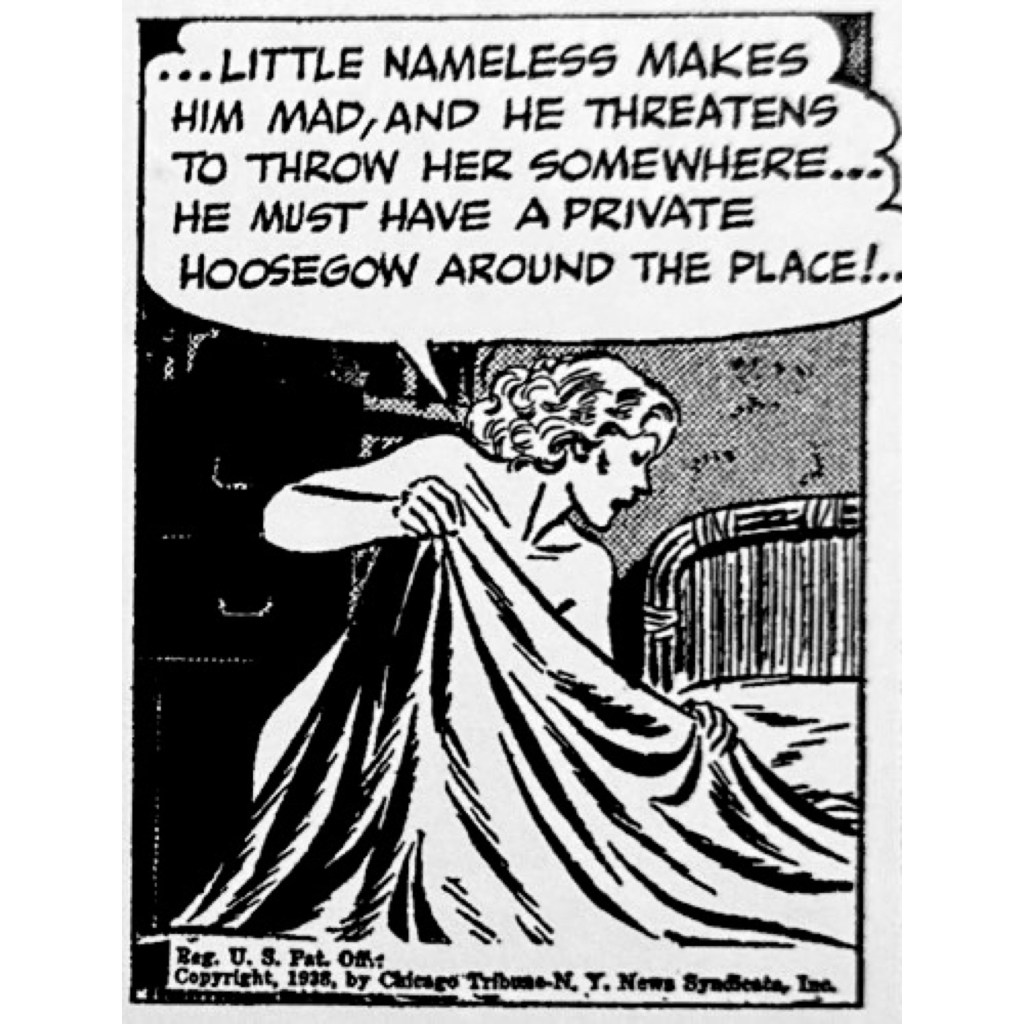

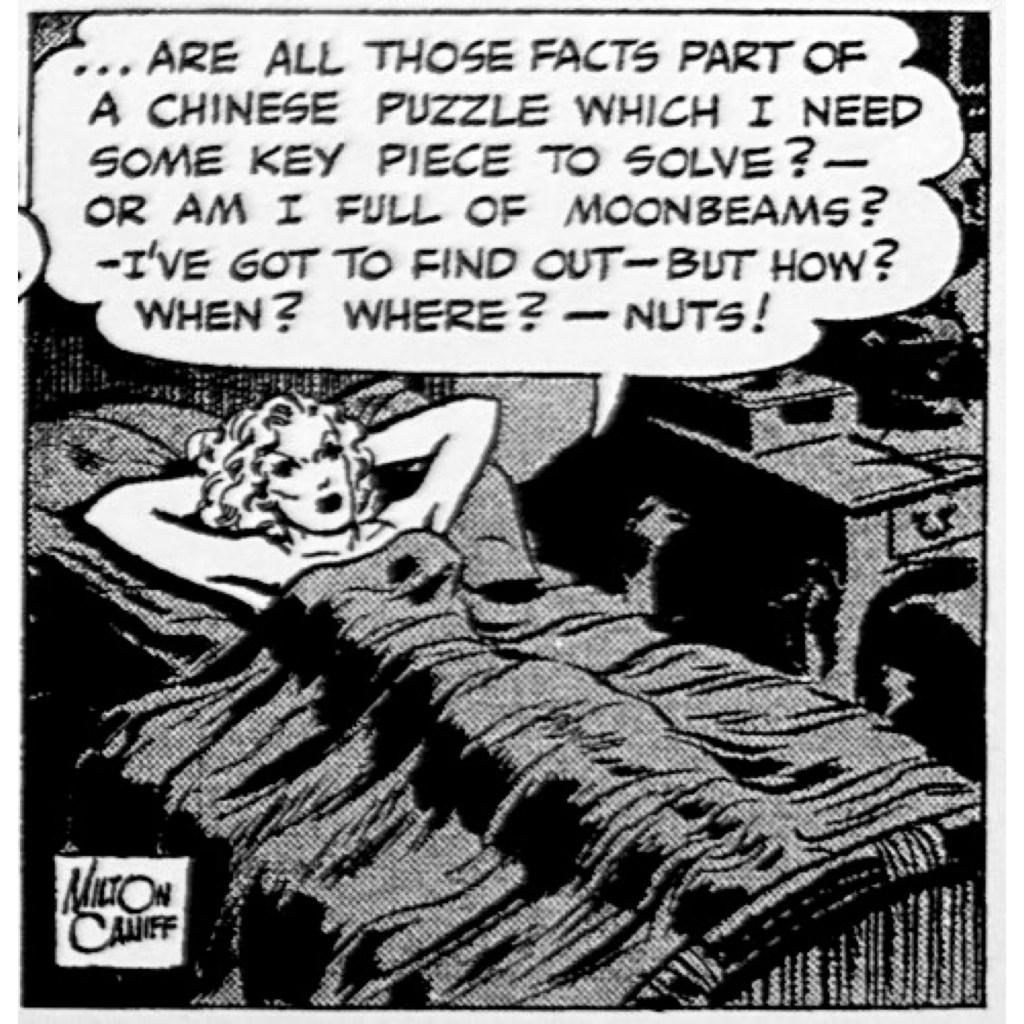

Slipping a bit of light erotica into the back pages of the buttoned-down newspaper medium was something of a sport among many comic strip artists throughout the last century. From the ubiquitous Gibson Girls of the the 00s to the curvy and well-delineated flapper daughters and office gals of 20s strips to the imperiled damsels and femmes fatale of 30s adventure, cartoonists understood they were wedging adult cheesecake into a “kids’ medium. Milton Caniff understood the better than anyone the potential here for serving the needs of a daily adventure strip while also pushing the boundaries of the conservative editorial propriety of national syndication.

Continue reading