A 43-year-old man, something over 3 feet tall, is dressed in the signature, foppish, Buster Brown garb and wig. He commands his trained dog Tige to do tricks and then engages an audience of schoolchildren, sometimes hundreds, and prompts their pledge only to wear Buster Brown shoes. It was a good pitch in 1906. For local shoe merchants who secured this road show from the Brown shoe Company, “the scheme is the best they ever tried,” reported the trade publication Profitable Advertiser. This was the dawn of mass media celebrity endorsements and syndicated point-of-sale marketing programs.

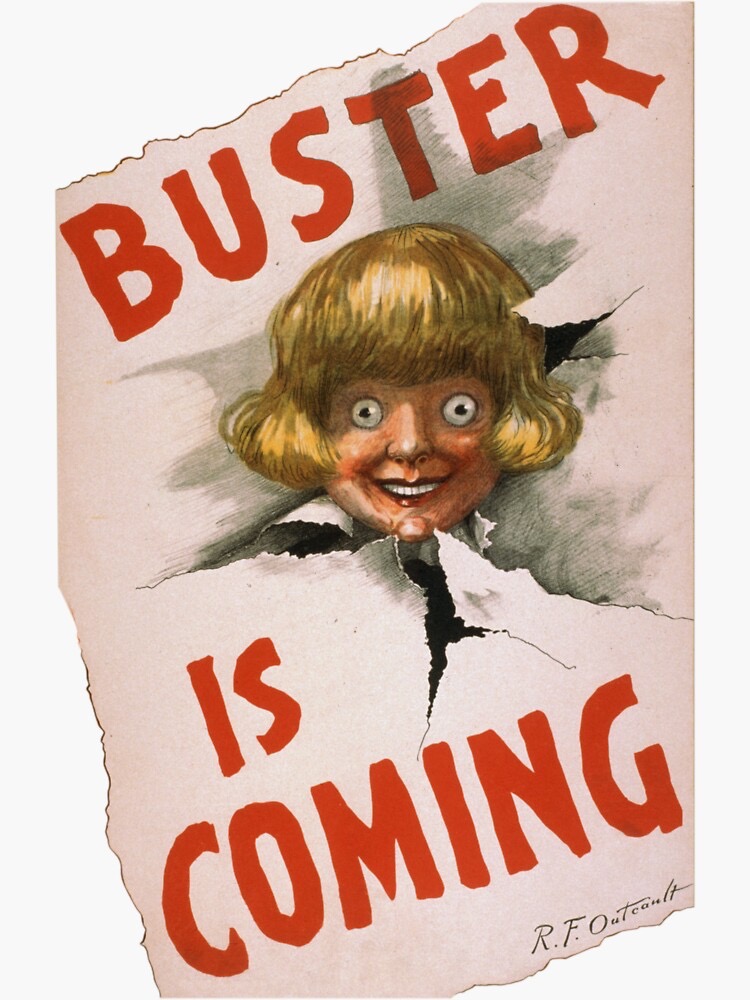

By the time creator R.F. Outcault started licensing his spectacular Buster Brown comic strip character in 1904, its boyish pranks and domestic chaos were familiar to audiences across the nation. Soon after premiering on May 4, 1902 in The New York Herald, the strip became a national sensation. At first blush, Buster seems an unlikely brand ambassador. Along with the Katzenjammer Kids and the many other copy cat pranksters of the “Sunday Supplements,” he was a quintessential comics “smart boy,” just more obviously middle class. His were the kind of antics that were commonly denounced by social reformers, clergy and teachers’ associations for their cruel pranks and disrespect for authority. And yet, here he was, his weekly sins somehow whitewashed by commodification. When Outcault sold licensing rights to the Brown Shoe Company in 1904, and launched the partnership at the St. Louis World’s Fair that year, he was also contracting Buster out to another 200 brands.

But it was the Brown Shoe Company that elevated the Buster Brown partnership into one of the longest-running comic character associations in history. And this was among the first examples of an emerging mass media ecosystem driving a new consumer culture of mass consumption. Brown not only married a celebrity to a mass produced and distributed product, but it showed how to standardize and syndicate a marketing program to a new nationwide market. Along the way, the Buster Brown marketing program pioneered marketing directly to kids in order to influence their parents’ buying habits.

Dubbed “Reception Tours,” the model provided for a Buster actor and a Tighe for day-long visitation to the retail outlet to drum up attention and drive shoe sales for the shoes. According to the St. Louis government’s history site, the Brown company hired up to 20 “midget” actors and trained dogs to staff the many road shows, which ran until 1930. But a forgotten article, “Buster Brown, Advertiser” in the obscure trade paper Profitable Advertiser gives us a more detailed look at “how the scheme is worked.” Retailers who agreed to buy at least 50 dozen pairs of Buster Brown shoes could access the program from Brown. The company provided a package that included the talent as well as marketing templates for local newspaper ads and handbills which the retailer agreed to buy in support of the Reception.

In this 1906 iteration, the company hired a 3-foot tall, 43-year old former salesman and “orator of ability,” Major Ray. In a trip to the town of Berwick, Buster and Tighe enjoyed a full day touring the local sites and manufacturing plants, visiting local officials and leading a parade through town. These tours became wildly popular local events. A Brown salesman claimed that “There were in the neighborhood of 8,000 to 10,000 people out to witness the reception.”

But Buster and Tighe kept their aim at the sales job. As Profitable Advertiser describes it, organizers scheduled the parade to pass local schools around dismissal time. Kids would gather back at the shoe store (or even rented theaters) to watch Tighe perform tricks and Buster entertain and pitch the crowd. They stood before a 30-foot banner across the store window declaring “Buy Buster Brown Shoes for boys and girls here. Every pair the best.” At times the crowd of youngsters were asked to raise their hands to acknowledge they will wear only Buster Brown shoes.

The Brown Shoe Company was writing the early scripts around modern media celebrity endorsement. Arguably, the American comic strip represented the first truly mass medium of the new century. Via newspaper networks and early syndication, premiere strips like Happy Hooligan, Katzenjammer Kids, Foxy Grandpa and Buster Brown were read on the same day coast to coast, a simultaneous, communal experience. That common content drafted nicely onto the new processes of mass production and distribution in manufacturing. Commodities now needed national identities. Consumer product branding emerged at precisely the time national entertainment heroes emerged in comic strips and soon in movies. The marriage of branding and celebrity seems natural and inevitable in part because they both came from a common source, the nationalization and standardization of both media and consumer goods. Consumer culture was being born, and in Buster Brown Shoes we see one of its weirder contours. Characters could be made into anodyne brands, while inert commodities could be given the gloss of personality.