It has been a minute – or maybe a year? – since I rounded up my favorite books that revive or explore the great American comic strip or pre-code comics. I don’t know why we are experiencing such a torrent of good reprints from major publishers as well as a number of small enthusiast presses rediscovering artists. My hope is that a new generation of graphic storytellers are being inspired by their predecessors. The graphic novel genre has gone mainstream, and that means our respect for visual storytelling has evolved. And so in various ways the history of the modern comics medium has become important to help fuel the imaginations of a new generation of artists. Let’s dig in.

Continue readingTag Archives: Reviews

The Banality of Villainy: Syd Hoff Eats the Rich

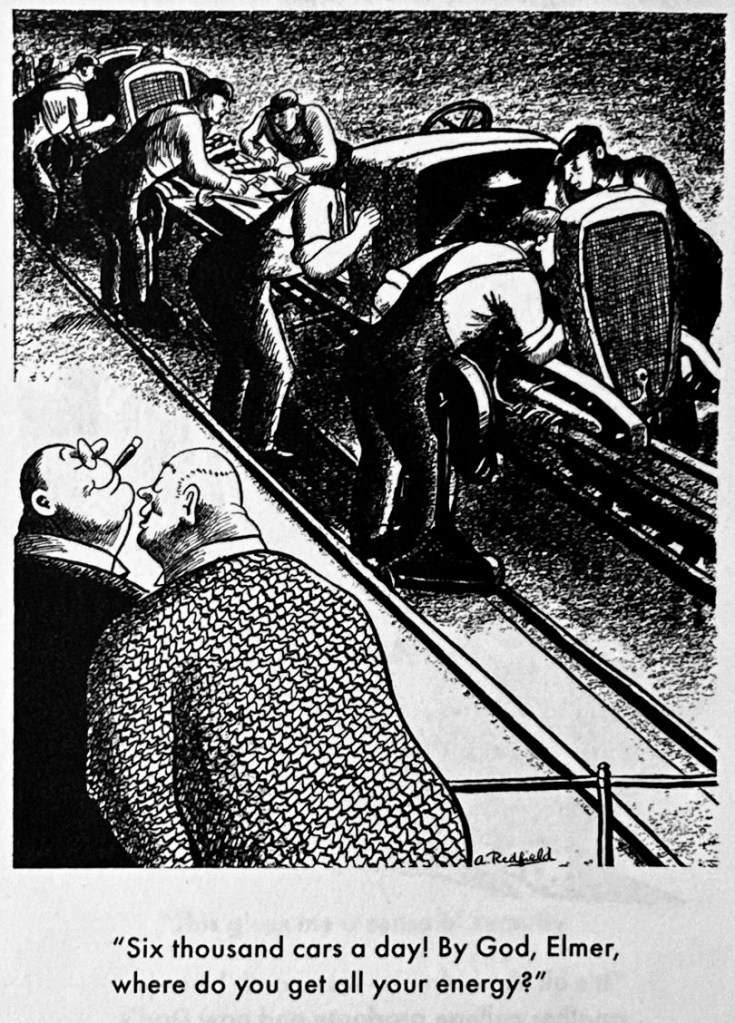

Caricature, when done well, is the art of clarification through exaggeration. Which is not the same thing as simplification. The best caricaturists exaggerate, enhance, underscore and highlight some physical or character attributes that express a deeper insight about its subject. Thomas Nast’s iconic Boss Tweed was not just obese with graft. He was gelatinous, overwhelmed and almost inert from his own power and greed. It was a portentous portrait. It argued visually the seeds of Tweed’s own destruction, an appetite for power that was overcoming his own control and better judgment. It did what caricature does best by attaching ideas and arguments to figures in ways that reach beyond simple journalistic proof or language. And because political and social caricature almost always personifies issues, it tends to explain social problems as aspects of human imperfection.

Continue readingBest Books of 2022: Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos

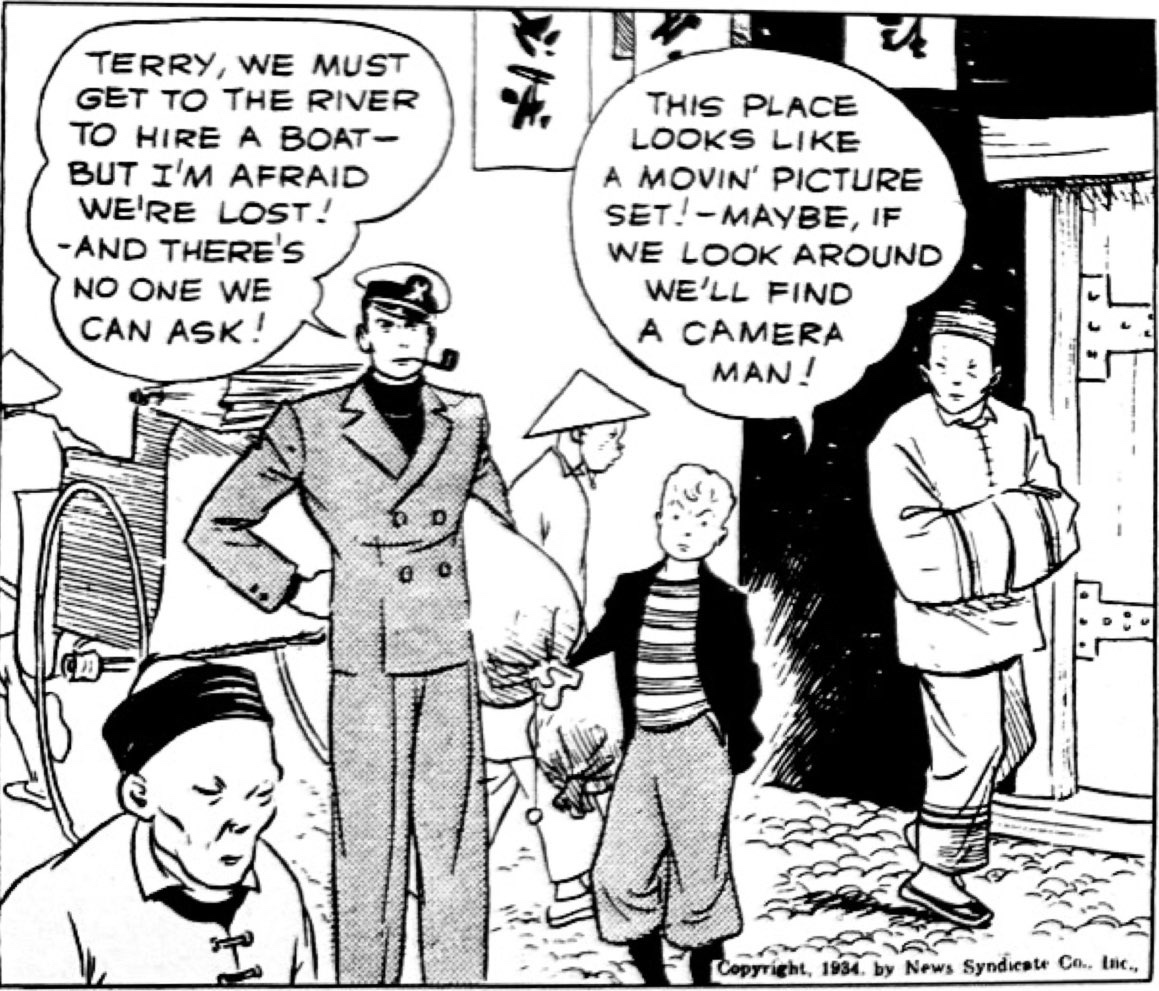

Bungleton Green was the longest running comic strip in the history of American Black newspapers, and an extended reprint of its greatest, wildest period during WWII is long overdue. But New York Review Comics has come through with this well-designed volume embracing artist Jay Jackson’s 1943-1944 sequence Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos. The strip began in 1920 with Leslie Rogers’ rendering of his eponymous character as a comic shirker, gambler and goof in the model of Moon Mullins or Barney Google. When the Chicago Defender’s prolific cartoonist Jay Jackson took the reins in the early 1930s, he made Bungleton into more of an adventurer, riding a genre that dominated the 1930s with Dick Tracy, Terry and the Pirates, Flash Gordon and Little Orphan Annie. Meanwhile, Jackson was also freelancing artwork for the science-fiction pulps and honing his skills as a “good girl” artists, skills that would soon inform a major turn in his weekly strip work.

Continue readingBest Books of 2022: Terry and the Pirates – Master Collection

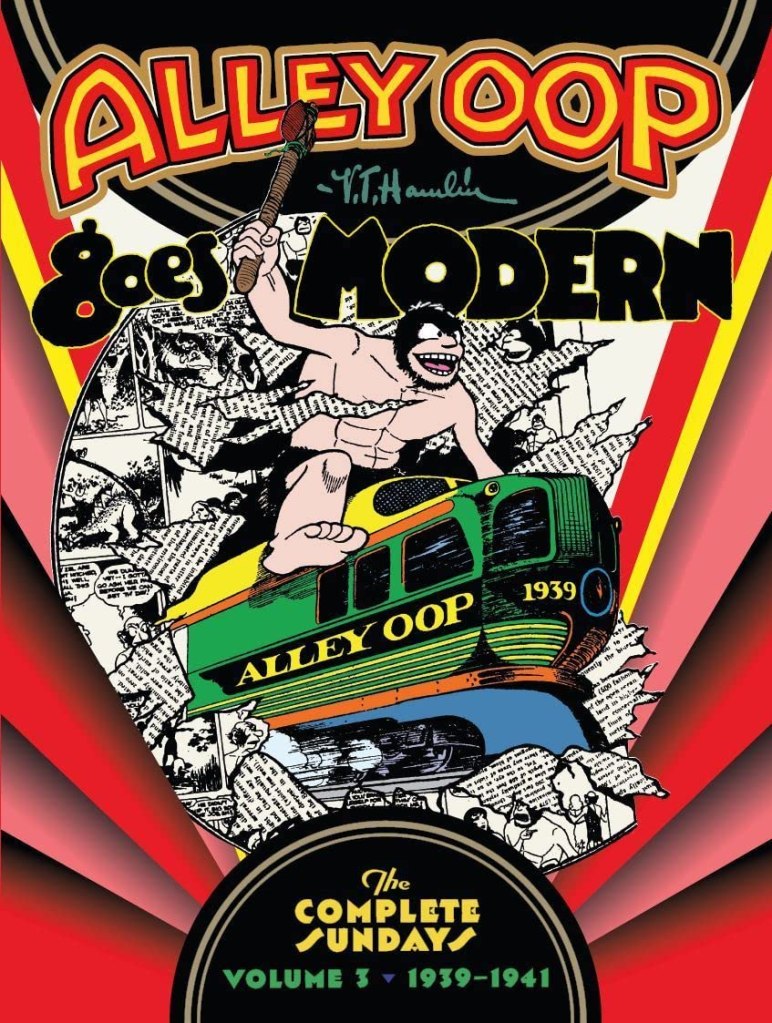

There are many reasons to celebrate and treasure this year’s most lavish reprint project. More than a decade after its inaugural Terry and the Pirates reprinting, the Library of American Comics revisits the pioneering adventure strip in a planned 13 volume, 11×14 format and using much better source material. This is the clearest look we have ever had at Milton Caniff’s masterpiece. But the best part of the project is the regular, compressed calendar on which LOAC is releasing quarterly volumes.

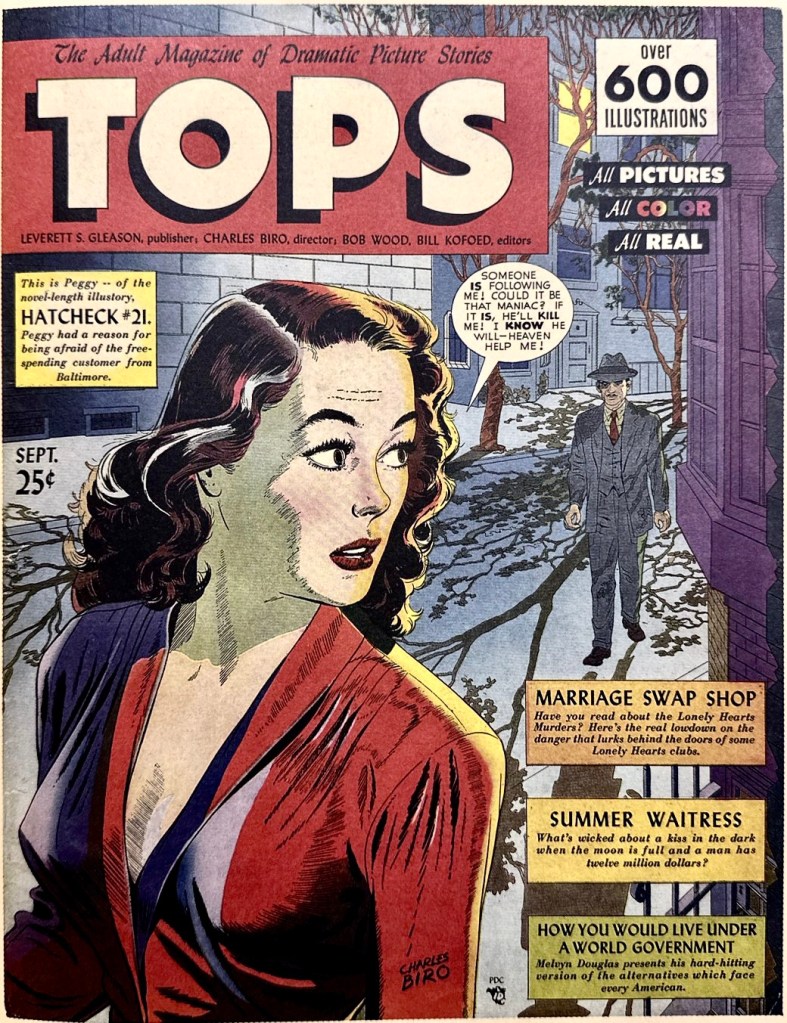

Continue readingBest Books of 2022: TOPS – When the Comics Tried Adulting

While this blog focuses mainly on the American comic strip in the first half of the last century, we have a soft spot here for comic books of the pre-code, pre-superhero era. For a brief shining moment after World War II, the comic book medium tried in vain to lurch into adulthood. Romance and crime genres especially aimed for older audiences. And the trend peaked with the horror, suspense and sci-fi comics of EC. The backlash was severe. Political hearings threatened government regulation, which the industry pre-empted with a self-censoring “Comics Code” that effectively consigned the American comic book to decades of the arrested adolescence of the superhero genre.

Continue readingBest Books of 2022: Gladys Parker

I have called Trina Robbins a national treasure more than once in these pages, and she just keeps impressing me with her championing women cartoonists. Her latest and long-awaited Gladys Parker: A Life in Comics is one of the truly indispensable reprints of the last year. Parker was a fiercely independent fashion designer and artist, one of the most famous cartoonists of the 30s and 40s, and best remembers for her Mopsy strips and comic books. Like Nell Brinkley before her, Parker insisted that fashion was anything but frivolous. It was part of the artistic landscape of modern America and an important vehicle for self-expression among modern women who were constrained and limited in so many other ways.

Robbins’ book not only gives Parker the biography she deserves, but packages its generous reprinting of her work in one of the best-designed books on comics this year. More of Parker and her work in my homage earlier this year.

Best Books of 2022: Minority Report: Revisiting Bootsie/Breezy/Dayenu Dayenu

One of the biggest blind spots in the history of American comic strips is the community newspapers that spoke to and out of the ethnic minority experience for decades. About Comics is engaged in one of the most important reprint projects in reprinting some of these overlooked comic strips. Throughout the 20th Century, Black, Italian, Eastern European, Jewish and other native and emigre minority communities generated newspaper networks that applied their own lenses to local, national and international affairs. They produced unique takes on modern American culture rarely seen from the dominant comics syndicates. Few of the comics artists and serial strips have been reprinted in any depth…until now. Their inclusion in the American comics canon is long overdue.

Continue reading