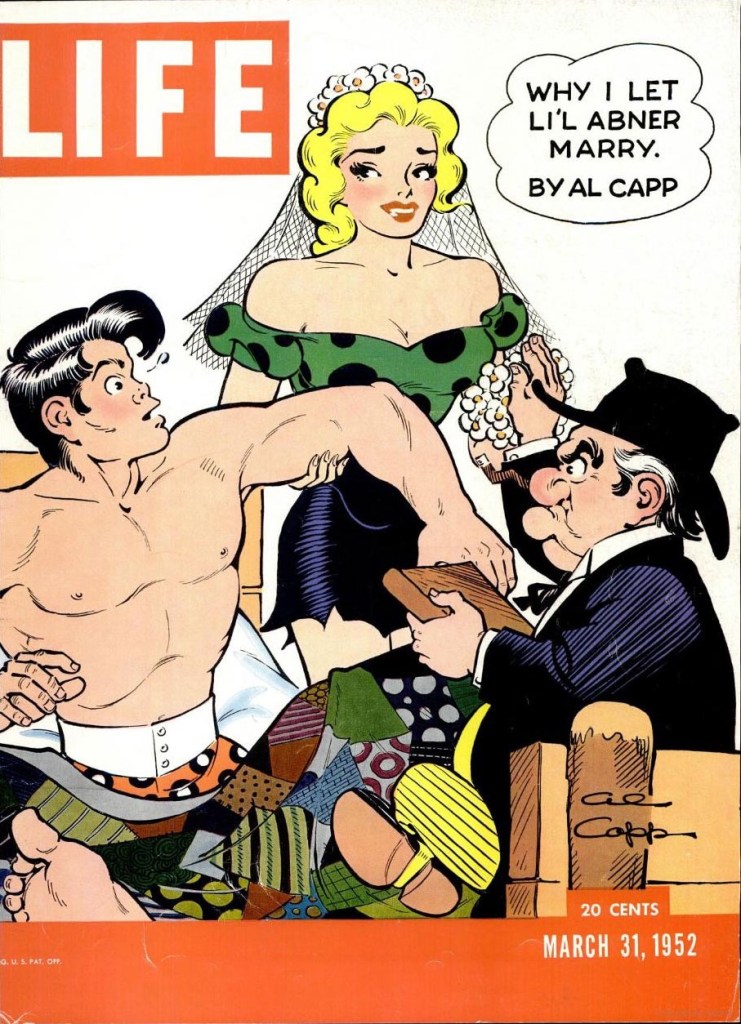

“It is a old comical strip trick – pretendin’ th’ hero gotta git married.” It keeps “stupid readers excited,” Li’l Abner claims in 1952. Days later he unwittingly weds Daisy Mae, ending a nearly 20 year tease. But this time it was no “comical strip” trick. In fact, several perennial bachelors of the comics pages fell in a post-WWII rush to the altar. Along with Abner, Prince Valiant, Buz Sawyer, Dick Tracy and Kerry Drake all enjoyed funny page weddings between 1946 and 1957. Comic strip heroes were just following the lead of the real-world heroes returning from WWII. Desperate to make up for lost time and return to normality, over 16 million Americans got hitched in 1946, the year after war ended in Europe and the Pacific. But each of these strips framed the new normal in American life differently. As the best of popular art often does, Vale, Dick, Abner, Buz, Kerry and their mates offered Americans a range of stories, myths really, about what this new normal meant.

I Love Aleta

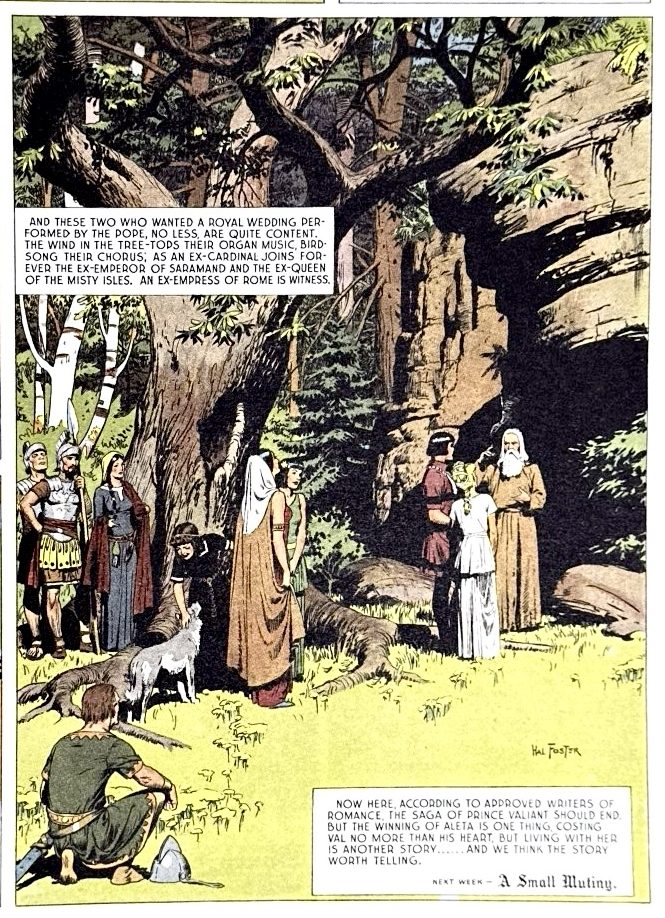

Ironically, the leading historical adventurer was the first to follow the contemporary trend. In 1946, Prince Valiant and Aleta, Queen of the Misty Isles, had been “dating” only a few comic strip years before they tied the knot. Their initial plan was to be married by the Pope, but a siege of Rome interfered. Setting a pattern for subsequent cartoon weddings, theirs was done off-plan. A hermit ex-cleric is recruited to bond the two in a scene that gives creator Hal Foster an opportunity to paint a visual and lyric idyll. “And these two who wanted a royal wedding performed by the Pope, no less, are quite content. The wind in the tree-tops their organ music, birdsong their chorus; as an ex-Cardinal joins forever the ex-Emperor of Saramand and the Ex-queen of the Misty Isles.”

While set in centuries past, Foster’s Val was channeling the postwar spirit in a number of ways. Even the adventure heroes that flourished in 1930s and 40s comics pages were settling down. The marriage boom of 1946 was but a starting gun in a cultural race towards a buttoned down American 50s. The GI Bill of 1944 helped finance a generation of veterans to get job training, college and home loans. This fueled a more corporatized, suburban, consumer culture typified by nuclear families, split level tract housing as well as a flight from the horror and chaos of war. After a Depression that threw up to a quarter of men out of work, and a war that killed over 400,000 Americans, creating a “normal” family life became a new American sacrament. Restoring men to traditional roles as providers and family heads was central to the new mythology of progress. And that was not unrelated to the funny pages, which had embraced outsized adventure heroes in the 1930s. From the comically powerful Popeye and Li’l Abner to the stoic square-jaws, Flash Gordon, Pat “Terry and the Pirates” Ryan and Dick Tracy, the hypermasculine do-gooder was a fantastic response to a Depression that challenged American manhood in profound ways.

But by 1946, pop culture was clearly retrenching to the new normal. The sudden crash of the superhero comic book market after the war was the most dramatic sign that the taste for male bombast waned quickly. Consider Alex Raymond’s major pivot. Until 1944, when he joined the Marines, Raymond had been responsible for an icon of eccentric masculine prowess, Flash Gordon. In 1946, he gives us Rip Kirby, a spectacled, pipe-smoking, stylishly urban and urbane sleuth. Suddenly, adventurous manhood could represent institutional authority and expertise rather than rebel from it. Rex Morgan, M.D., Judge Parker and Kerry Drake all had suit, ties and credentials. Even our space race and spy heroes were, after all, company men. So what was pop culture to do with all of these legacy men’s men? Well, let’s get some of them to the church on time, for starters.

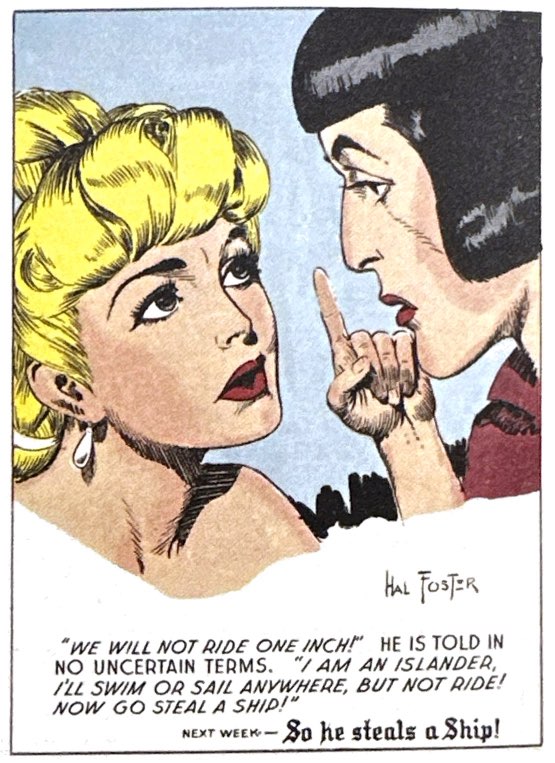

And while we are at it, let’s get those wartime working women back into the home, even if we have to mock, cajole and stereotype them there. Even in Hal Foster’s Arthurian past we see the dynamic at work. Within a few panels of their marriage Aleta becomes a demanding scold, insisting she travels only by water. “Now go steal a ship” she commands. But the true “I Love Lucy” moment comes shortly after their marriage when Aleta follows her new husband on his next adventure, disguised in a silly metal helm as “Sir Puny.” Foster, Val and the knight-bros tease, prank and placate Aleta’s comic attempt to join this man’s world with the typical condescension that 50s TV dads reserved for handling nonsensical children and ambitious wives. Women’s roles in popular fiction after the war didn’t just pivot so much as fully retreat. The quick-witted independence of Katherine Hepburn, Mae West, Rosalind Russell and Barbara Stanwyck gave way to airheaded bombshells (Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, Jane Russell) and kitchen-bound wives. After all, the signature sitcom of 50s America, “I Love Lucy,” was a weekly reminder that feminine ambitions beyond the home were the stuff of farce.

It is in this complicated context that the post-WWII adventure strips gets interesting as old comic strip pros recalibrate their formulas with new dynamics.

Dick Tracy In Love…Sorta

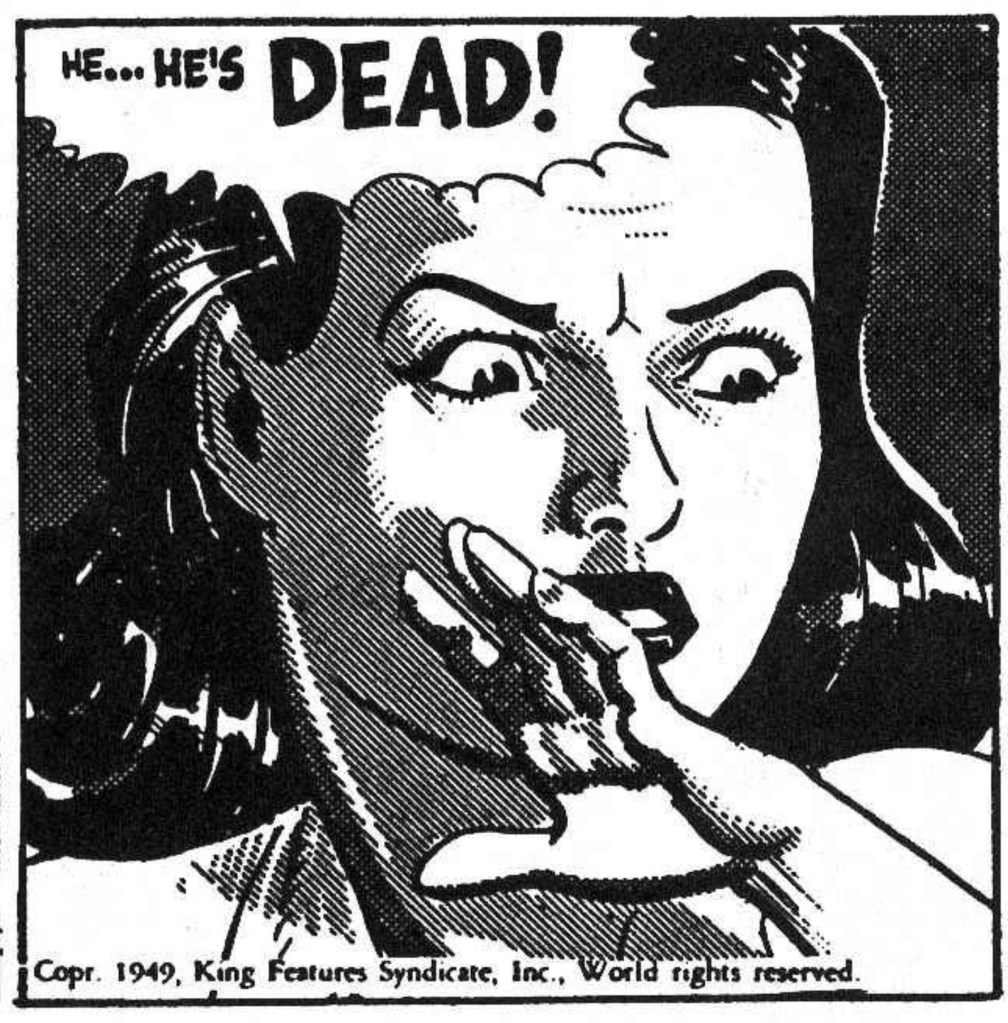

First off, our heroes (and their creators) need to get uncharacteristically mushy…if only for a moment. Comic strip aficionados will not be surprised that Chester Gould had a thoroughly repressed way of wedding Dick Tracy to the remarkably patient Tess Trueheart on Christmas Eve 1949. He chose not to show us. After a 19 year engagement, which was part of Dick’s origin story as a policeman, Gould couldn’t even bring himself to show us the ceremony. In a series of winks to the audience in the December daily strips, it is clear something is preoccupying both Dick and Tess. The big Christmas Day Sunday reveal comes after the two get hitched on the sly and assemble the Tracy gang for a surprise celebration in the new home Dick bought, also secretly.

Why all the subterfuge? Who knows? Like Tracy himself, Gould appears to be uncomfortable with softer emotions. He seems to prefer depicting rage, revenge, righteousness balanced only occasionally by the most maudlin moments of sentiment. Their honeymoon gets interrupted by Dick pursuing a suspected murderer. Tess returns home alone in a huff as her missing husband gets dragged by a car to within an inch of his life. After all of these years, Gould devotes more panels depicting poor Tess grousing about her new husband’s unexplained disappearance than any romance. The world’s most famous cop is, in the end, all business, as is his creator. Gould’s generally one-dimensional and often condescending depictions of women had been baked into the strip almost from the beginning…and he rarely wavered. Like much else in the Dick Tracy universe, marriage seemed more iconic than deeply realized, a potential plot device rather than a turning point. Tess and Dick’s first child, Bonnie Braids, for instance, appears mainly when kidnapped, imperiled or posing for the annual Christmas greeting strip. In the Gould/Tracy cosmos, it isn’t that marriage and family don’t matter so much as they simply extend an existing collection of work colleagues, adoptees, friends and acquaintances (the larger community) our lawman hero defends.

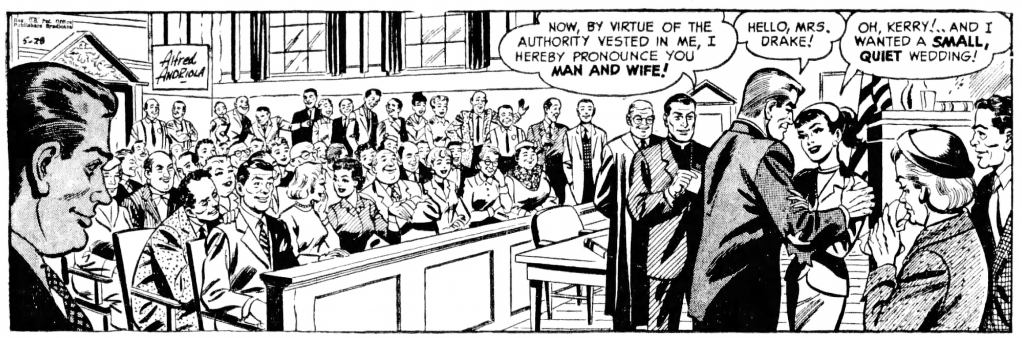

Likewise, the 1958 marriage of Dick Tracy wannabe Kerry Drake, had little apparent impact on that no-nonsense detective’s life. Another institutional hero of 1950s comicdom, Kerry Drake was conceived by artist Alfred Andriola and writer Alan Saunders as an investigator for the District Attorney’s office. The two romances of his life were attached to tragedy. His first fiancée and secretary, Sandy Burns, was murdered in a 1953 mystery that took Kerry another year to solve. But in 1958, his high school acquaintance Mindy Malone reemerges as the widow of Kerry’s slain partner.

Like Dick and Tess’s marriage, Kerry and Mindy’s is barely a burp in the overall trajectory of the strip. Crime takes no romantic holiday for this couple either. Kerry is kidnapped and misses the planned wedding ceremony. But while hauling the captured villain into headquarters, he yanks Mindy into a courtroom, recruits the police chaplain, and marries the gal. Within days at a honeymoon stopover, a dead body is found in Kerry’s trunk and a new mystery commences. For the time being Mindy recedes into being Kerry’s sounding board. Many years later, and after giving birth to quadruplets, Mindy and the enlarged Drake clan become more of a centerpiece.

But two comic strip marriages do stand out for the different ways their creators used these trends to address post-WWII culture.

“Hopelessly, Permanently, Married”

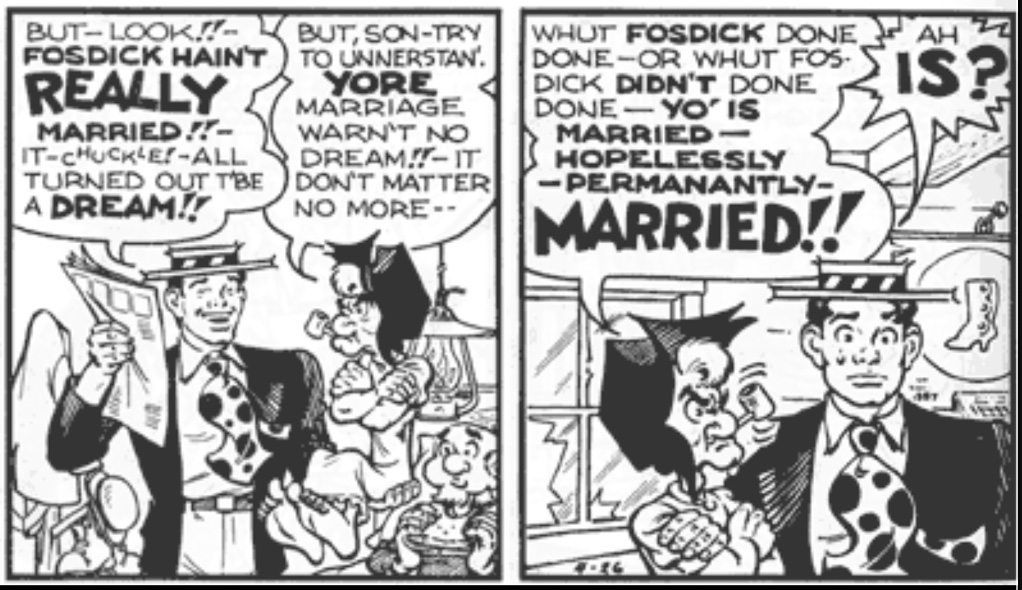

Al Capp understood better than anyone that Dick Tracy and his creator were irredeemably tight-assed and humorless. In fact, his famous strip-within-a-strip send-up of Tracy, Fearless Fosdick, was a direct cause of the highest profile cartoon marriage of the post-war years. Li’l Abner had sworn to mirror in his own hillbilly life whatever his favorite comic strip hero Fosdick (“Mah Ideel!”) did in the daily funny pages. When the inflexible dimwit Fosdick must marry his repulsive gal Prudence Pimpleton, Abner is cornered by his own devotion to the strip. The best promoted, least romantic, cartoon marriage of them all occurred in the daily strips on March 29 and 31. A stunned Abner in his PJs and still in bed gets hitched to a veiled Daisy Mae Scroggs by Marryin’ Sam (“$1.35, Please!”).

If this all seemed like a rushed and unsentimental affair, it was because Abner and Daisy Mae’s marriage represented domestication in the worst possible sense. This was not just the end of that stereotypical bachelor life, Capp argued quite seriously in the LIFE features. This episode marked for him the loss of a greater freedom in art and the country. “For the first 14 years I reveled in the freedom to laugh at America. But now America has changed. The humorist feels the change more, perhaps, than any one. Now there are things about America we can’t kid.” He bitterly recalled how his Schmoo (1948) and Kigmy (1949) satires were denounced by some as unpatriotic. “It implied some criticism of some kinds of Americans and any criticism of anything American was (now) un-American?,” he wrote. “So that was when I decided to go back to fairy tales until the atmosphere is gone. That is the real reason why Li’l Abner married Daisy Mae.” But the low point in the Li’l Abner marital story comes during the honeymoon, when Fosdick’s marriage is revealed as just a dream sequence. Abner’s fantastic connection to “mah ideel!” is punctured. “Whut Fosdick done – or what Fosdick didn’t done done – yo’ is married – hopelessly – permanently – married!!” Mammy scolds him. Capp may be telling us that the real casualty in this episode was the vital, playful connection between popular art and culture.

Buz, Christy and the New Myth of Marriage

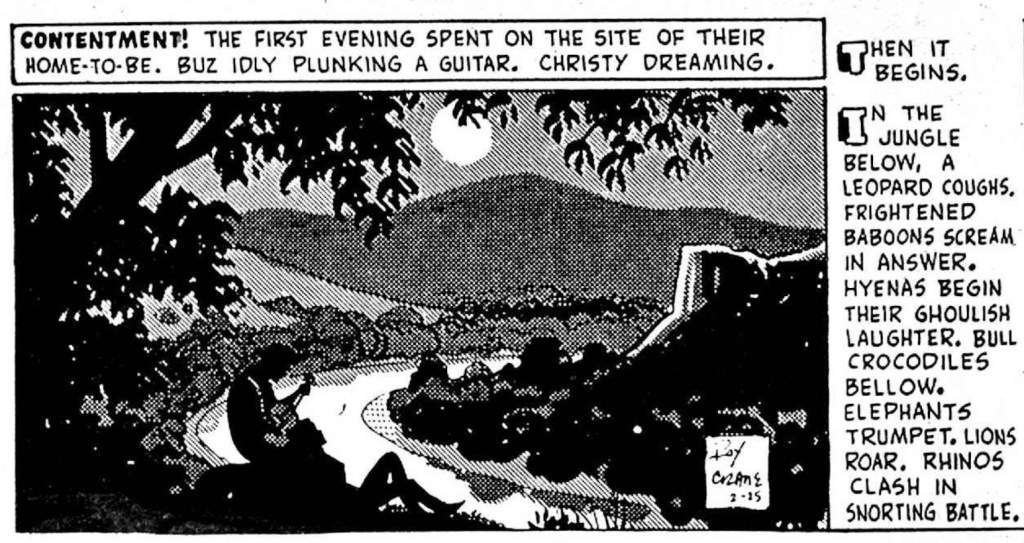

No American hero strip took romance and the tension between adventure and domesticity as seriously as Buz Sawyer. The wedding itself, on Dec. 13, 1948, was the most conventional and planned of the comic strip ceremonies during this marriage boom. And Buz is depicted as a two–fisted hero who has been fully disarmed by love. Crane and Granberry use much of 1949 after the wedding to explore their relationship and give his wife an assertive and adventurous character of her own. During their beachside honeymoon, the strip discreetly cuts away to a side quest – a comic hunting trip in which Buz’s BFF Sweeney bags a Bighorn Sheep to present it skin as a wedding present. It is ugly and it reeks, but Christy reminds Buz, “The thing this sheepskin stands for — love, loyalty and devotion – you can’t buy.”

In fact, Christy’s comment suggests that Crane/Granberry are themselves working self-consciously in a symbolic mode at this point. And they send the newlywed couple on a metaphorical journey into constructing a modern marriage that itself creatively marries symbols of adventure and domesticity. The first six months of Buz Sawyer strips in 1949 are both visually enchanting and thematically rich a fantasy of post-war domestic bliss.

Former tomboy Chisty is game. She refuses to let Buz languish in the urban desk job his employer offers the newlywed. She joins him on his next assignment to Africa to create a settlement out of barren tundra for a drilling well test. Buz’s Frontier Oil is aptly named, because the entire African episode is a journey to the roots of human civilization in which Buz and Christy literally build a town, a home and their relationship out of primordial mud. It is a tour de force.

Exercising all of his considerable skills depicting foreign landscapes, Crane crafts an Africa that is at once breathtaking and brutal. Beautifully multi-layered vistas are punctuated by charging rhinos and bloodthirsty lions. He creates a natural world that is aesthetically dazzling but morally indifferent and predatory. In this ooze, Buz and Chirsty build their home out of slats and anthill mud and learn the basic rules of nature, predation and home as both haven and defense.

The African Honeymoon is an event-filled saga that I won’t retell in detail here. But its contours show Crane and Granberry recreating a compelling mythology of modern relationships and “settling down.” Buz and Christy build their Afro-suburban tract house out of mud and at-hand trees, which is both haven against a heartless natural world but hearth to nurture intimacy and interdependence. They define gender roles. Buz, the hunter-gatherer is also the world-wise skeptic who polices the relationship against human evil when the thorough rotter Kingston Diamond connives to woo Christy. Christy, the gardener/homemaker is also the naif who is too innocent and trusting but provides the relationship both conscience and civilizing force. And in the grisly end to this extended back-to-basics tale, Christy has to confront and defeat human evil. Not unrelated is the unfortunate touch of imperialism that tainted much of Crane’s world adventuring. The backward, obeisant and manipulable natives in Crane and Granberry’s Africa play their stereotypical role as props that justify white exploitation.

Crane and Granberry are mythologizing the “settling down” of post-war America by connecting it with primordial civilization-building. And Americans after WWII seemed hungry for this kind if myth-making. At the same time ultra-modern suburban lifestyles and urbane civilized heroes like Rip Kirby and Rex Morgan nudged into pop culture, the Western genre hit its apex. Cowboy and frontier dramas overwhelmed every other genre in film and TV especially. While the western genre often provided fantasies of individualism and independence for an era of conformity and interdependence, it was a rich genre that supplied diverse myths. Much of the genre was less about the “wild west” than it was about settling the frontier, family as social building block, law and social order, taming nature and individualist instincts. Remarkably, Buz Sawyer in 1948-49 was anticipating America’s embrace of fictional pre-modern worlds in order to rationalize its move into a modern future.

Crane and Granberry are mythologizing the “settling down” of post-war America by connecting it with primordial civilization-building. And Americans after WWII seemed hungry for this kind if myth-making. At the same time ultra-modern suburban lifestyles and urbane civilized heroes like Rip Kirby and Rex Morgan nudged into pop culture, the Western genre hit its apex. Cowboy and frontier dramas overwhelmed every other genre in film and TV especially. While the western genre often provided fantasies of individualism and independence for an era of conformity and interdependence, it was a rich genre that supplied diverse myths. Much of the genre was less about the “wild west” than it was about settling the frontier, family as social building block, law and social order, taming nature and individualist instincts. Remarkably, Buz Sawyer in 1948-49 was anticipating America’s embrace of fictional pre-modern worlds in order to rationalize its move into a modern future.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Recovering Hank: America’s Anti-Fascist Hero – Panels & Prose