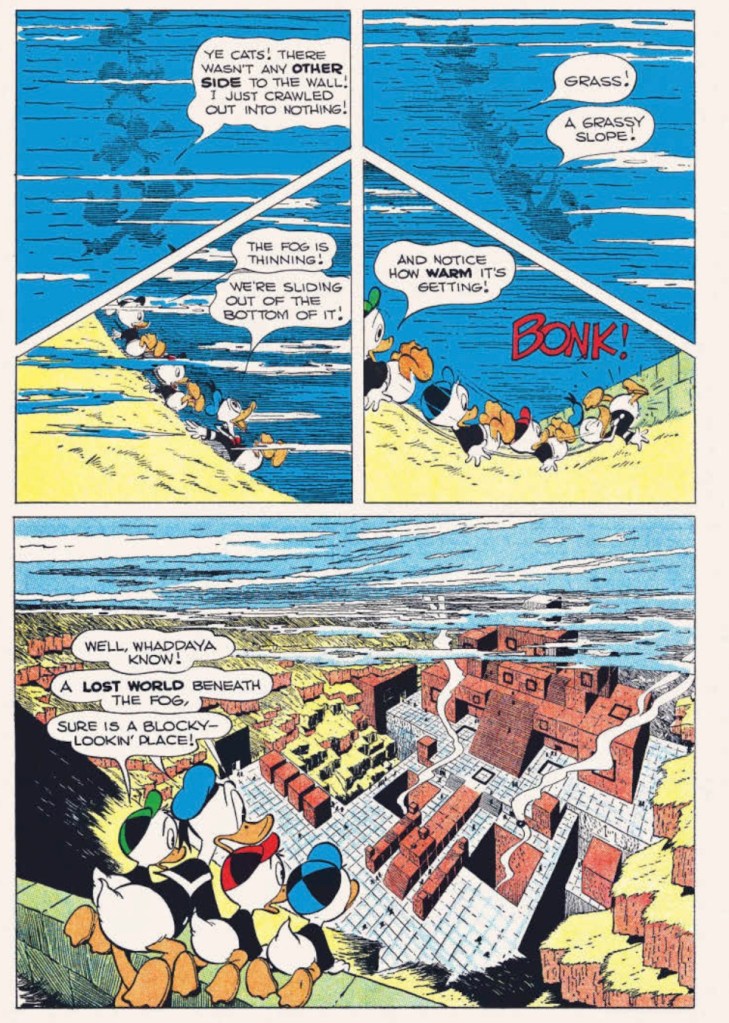

Is a bigger Barks a better Barks? Taschen’s long-awaited Disney Comics Library: Carl Barks’s Donald Duck. Vol. 1. 1942–1950 supersizes the Duck Man, and we are all the richer for it. This is one of their “XXL” volumes, so let’s go to the tape. It weighs in, literally, at 11+ pounds: over 626 11 x 15.5-inch pages that include the longer Donald Duck stories from 15 issues of Western Publishing’s Four-Color series. up to 1950. These include some of the greatest expressions of Barks’s quick mastery of the comic book format. In “The Old Castle’s Secret” (1948) he uses page structure, atmospherics and pace to create real suspense. His masterpiece of hallucinogenic imagination married to landscape precision surely is “Lost in the Andes” (1949). And his well-tuned sense of character is clear in creating a purely American icon of endearing greed in Uncle Scrooge in “Christmas on Bear Mountain” (1947). Of course we have seen these and many of the other stories in this collection reprinted before. So, to answer my own question, does scaling up Barks give us a better Barks?

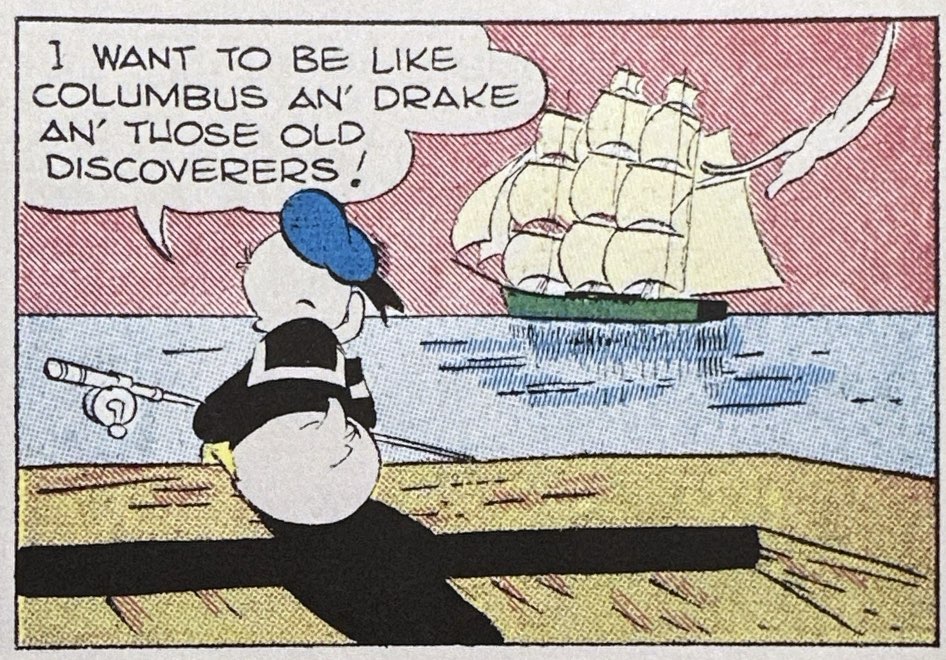

Yes, yes and yes, again! Barks was known to readers as “the good duck artist” long before his authorship was publicly recognized. But in retrospect, this volume just underscores how much more advanced Barks was than almost anyone else working in the still young comic book medium in the 1940s. While most superhero and crime comic hacks struggled with basic figure drawing, perspective and proportion, Barks was well beyond that. More importantly, he brought to the medium an understanding of character expressiveness, gesture nuance and story structure that you just can ‘t find even among the best comic book artists of his day. His Disney Studio experience left him with an ability to string gags into coherent structures and pace his audience through stages of a story. He quickly understood how a single page worked to maintain a mood and compel the reader onward. But most of all, he understood the power of character. He made Donald more than a hothead, but an emotionally complicated and imperfect everyman. The ever-present nephews and eventually Uncle Scrooge put interpersonal dynamics and competing sensibilities at the center of every story. His ducks were simply more human than the humans in competing comics genres.

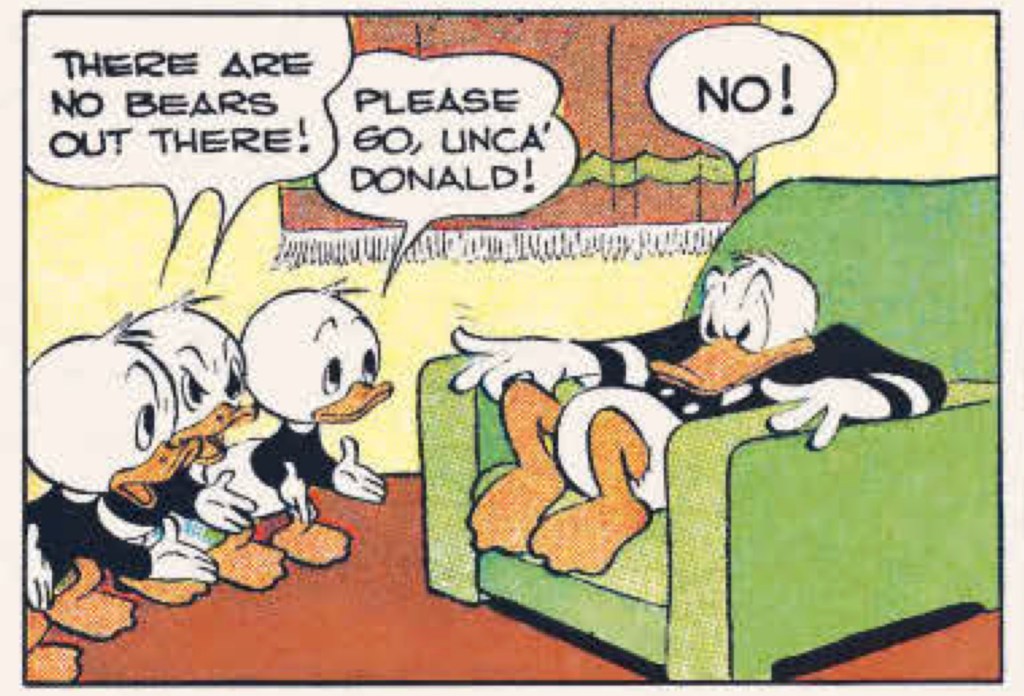

Consider a single panel from “Bear Mountain” of the boys pleading with Donald to go chop a Christmas tree. They register pleading, anger and befuddlement as he responds as much in posture and words, literally digging in.

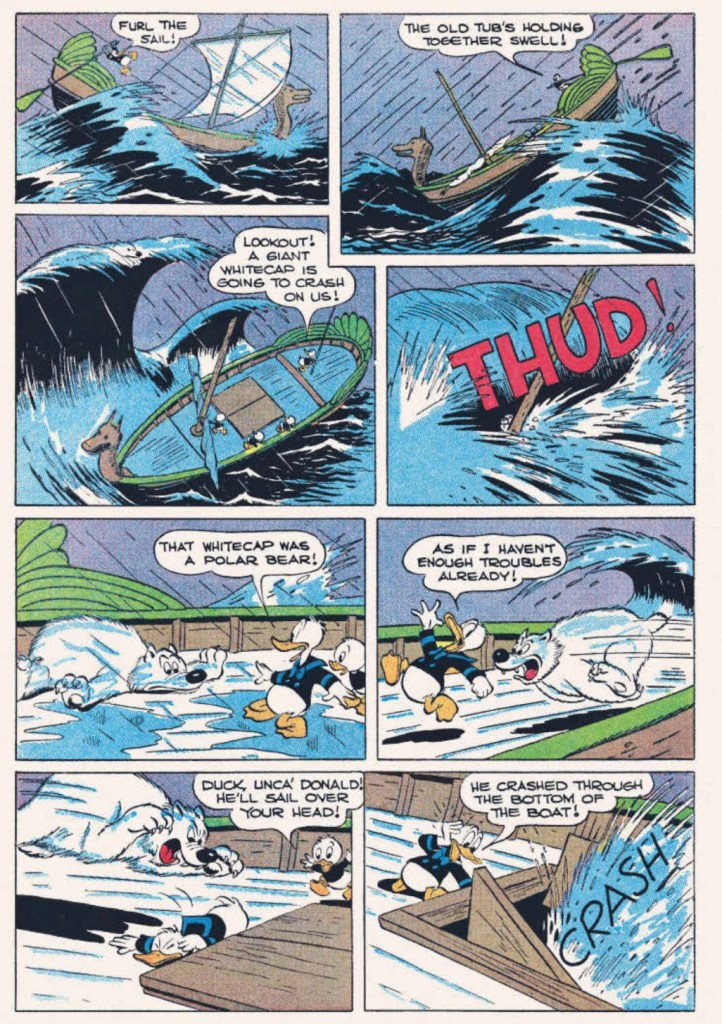

These are some of the qualities that struck me while swimming in these comics at such scale. You get a chance to focus in on the way each panel often has very distinct emotion or mood, even as it is part of a sequence of plotting or action. Of course, we know this stuff about Barks already. But, man, the panel size just seems to amplify Barks’s ability to use the nephews’s eye positions and head tilts to offer a tonal response to “Unca Donald’s” latest misstep. So much comes from so little here: duck posture, the fold of a walking webbed foot, the strut. And of course, when he mixes it up with non-cartoony double-wide landscape panels or action climaxes, that Barks magic sparkles.

Aside from size, Taschen’s style of reproduction is distinct here. It follows the general approach they have taken in their series of Marvel and EC reprints, working from original printed comics rather than proofs or original art. As they describe it: “Beginning with super-high-resolution photographs of high grade, top-quality comics from the Walt Disney Archives as printed more than half a century ago, we used modern retouching techniques to correct problems with the era’s inexpensive, imperfect printing. This included improved and balanced ink densities and color matching, proper registration of the four-color printing, and correction of thick / thin lines resulting from the flexible plates’ ‘smudging.’ The end result is a finished product — as if hot off of a world-class printing press, produced without economic or time-pressure costraints.”

Golden age reprints follow a range of reprint philosophies and reading experiences, each of which has its own costs and benefits. Many straight repros of comics pages try to convey a found-in-the-basement musty antiquity, only to suffer muddy hue differentiation and piss-tinted whites. Black and white repros often highlight the precision and detail of the line and inkwork but lose the mood and sense of depth that coloring adds. So-called color “restorations” replace the half-tone hues with solid, digitally applied colors that can run from posterized intensity to muted tones that try to approximate older printed pages. I would describe Taschen’s approach as a digitally enhanced recreation of the original comic book experience. The half-tone color dots are here, but they are unusually even and free of typical blotching. Likewise, the linework and lettering feel finer, more cleanly defined and registered with the color. It is a pleasing compromise among different techniques that I think works even better with the Disney comics than it did with Taschen’s EC and Marvel reprints. The variable thickness and sharpness of Barks’s line really pop. As the publisher describes, it feels like reading a comic printed under optimal technology on premium paper.

Jim Fanning’s serviceable, if not particularly critical, intro often seems more eager to discuss the greatness of Walt Disney and Donald Duck than Carl Barks himself. Still, we the key points in the poor, Oregon-born boy’s road to Duckburg. A hardscrabble childhood steeped in cartoon fantasies gave him an appreciation for escapism with a hard edge. His serial failures in a range of jobs left him to pursue a native art talent but only after exposure to a range of hard everyday lives. That Barksian blend of eccentric fantasy and unheroic human foibles was baked into his character – sentiment and sharpness. After working with risqué humor mags like Eye Opener, he landed an entry-level gig at Disney as an in-betweener. The studio soon recognized his talent and he became part of the duck team that evolved the Donald character into the most popular celebrity of the late 1930s.

The lessons he learned in that famous Disney thinktank atmosphere are obvious in the Donald comics he started creating for Western Publishing when he left Disney to go freelance in 1942. His artistic mastery were table stakes, even if they put him miles ahead of others working in comic books. He understood storyboarding, rhythm and timing, nuances of gesture, posture. And more than anything, he carried into the comics that Disney respect for the cartooning medium. He understood comics as an art that deserved careful thought and whose nuances could be discerned by the audience.

Typically, even Disney fanboys recognize that Donald was a necessary and welcome counterpoint to the affable but increasingly bland Mickey. His irascible nature was not only the daemonic “anti-hero” Fanning suggests. He helped the studio maintain an edginess and adult appeal even as it was veering towards its pristine, anodyne corporate identity. Donald was very much a product of 30s anger and frustration. His was a funny, unthreatening kind of rage with which Depression and war-wear Americans could identify. Barks understood best that there was humanity beyond the tantrums, however. He projected into the Donald of the comics a wide range of imperfections – envy, greed, vanity, competitiveness, vindictiveness – that at times eclipsed his overarching identity as a good Uncle. And I suspect this density of characterization drew even young kids in. Compare suburban provider Donald Duck to the saccharine “knows best” father figures of post-WWII TV and film. Maybe the kids reading this stuff so avidly sensed in Barks’s Duck universe something more real.

None of which undermines Barks creative talents or cultural contributions. In fact, my own fascination with Barks comes from the density of what he made. The Ducks are simple figures, doing simple comedy in simple worlds. Yet these comics resonate more than a half century later because our reactions to them are disarmingly complex. For what its worth, engaging these familiar comics yet again at this scale and resolution mad me sit back and think harder about why that is.

Which goes back to answering my opening question. Is a bigger Barks and better Barks? It was for me.

Discover more from Panels & Prose

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.