What made me think harder or differently about the comics medium in the last year or so? That is my main criterion for these occasional roundups of books mainly on comic strips but also about early comics. Some of the titles here are filling in holes in our understanding about the history of the comics forms. Others are calling attention to artists or patterns in comics history that I think bear more thought. And many were just plain fun. Feel free to comment on the books you found most enlightening or entertaining about the comics history.

The Metaphysics (Huh?) of Alex Raymond’s Death

Dave Sim’s (with an assist by Carson Grubaugh) The Strange Death of Alex Raymond (Living the Line) is crazy like a fox. Sim’s ostensible exploration of the tragic death of the highly influential artist behind Flash Gordon and Rip Kirby uses a batshit conceit that some “metaphysics of comics” somehow connects everything from Margaret “Gone With the Wind” Mitchell, Milt Caniff’s quiet envy of Raymond, the wives and lovers of multiple comics artists of the 50s, a few B-movies, and whatever the hell else you can imagine to car crash that killed Raymond in 1956. It is also batshit brilliant. It gives Sim the frame in which to recall (and even redraw) a vast swathe of American pop culture and artists that drove the changing styles of 1950s comic strips. At its most lucid, the book delineates the different realisms of Hal Foster, Caniff and Raymond, the development of the photorealistic style, even the nuts ad bolts of brush and pen work. Along the way, forced me to contextualize and appreciate strips like Big Ben Bolt, Twin Earths, and the post-Raymond Kirby years. He brilliantly injects a whining Charlie Brown into the history as Schulz’s aesthetic counterforce to the short-lived photo-realist era of American comics. An he forces us to think harder about the rise and fall of different comics styles. As others like Jerry Robinson and Scott McCloud before Sim have shown, there is nothing like a fellow craftsman dissecting his colleague’s work to deepen a viewer’s appreciation of the artistry and decisions that go into those four panels on any given day. Whether you can track Sim’s idea of metaphysics connecting all of these shards and rabbit holes is beside the point. It sets him up for some deft and truly illuminating rumination on the aesthetics of comics in their historic context.

EC At Scale

I am almost embarrassed to admit how many of IDW’s massive and pricey Artist’s Editions I own. How does one justify parting with $150 for each, even though they reprint in full detail and at original scale the actual final art from some of the great craftsmen in the field? And yet I never regretted investing in Artist’s Editions of early MAD issues, Will Eisner’s The Spirit, and the EC stories of Graham Ingels. This way-oversized scale and hi-def color images of black and white line art and marginal proofing notes seem to put you on the other end of the artists’ pens and brushes. This is even more true of the EC Covers Artists Editiion (IDW), which organizes the cover art of the famed EC comics stable by artist: Johnny Craig, Graham Ingels, Wally Wood, Harvey Kurtzman, Jack Davis and more. The covers of course were meant to be expansive, immersive teases of issue content, and so we get a single image splashed across the 15X22 page. Every bit of detail feels more like a deliberate, conscious decision, forcing us to think harder about the artist’s process. This is not just another trophy for collectors (or hoarders). It is a valuable experience for anyone who wants to deepen their understanding of the art.

The Golden Age of Wolverton

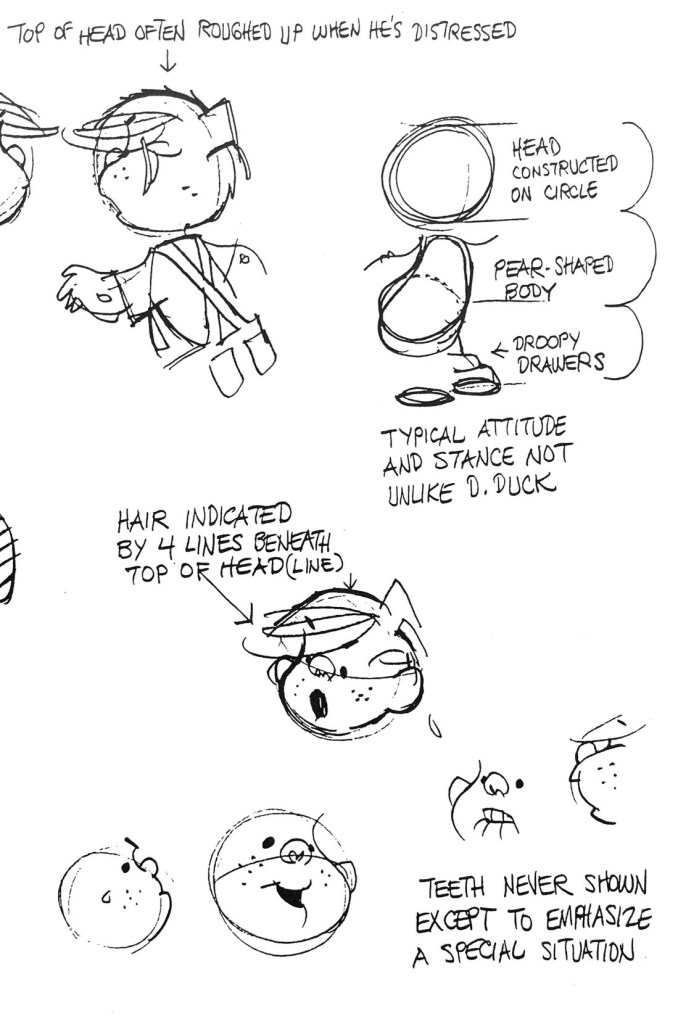

Fans of the grotesque pointillism of Basil Wolverton have been treated in recent years by Greg Sadowski’s exhaustive two-volume biography and reprinting in Creeping Death from Neptune and Brain Bats of Venus (both Fantagraphics). While those two volumes focused more on Wolverton’s horror and sci-fi work, this year’s Scoop Scuttle and His Pals: The Crackpot Comics of Basil Wolverton (Fantagraphics) is a retrospective of the artist at his madcap best. Ironically, many of these screwball and slapstick series were the fruits of failure. Wolverton conceived of Scoop Scuttle, Bingeing Buster and Jumpin’ Jupiter as daily comics and repurposed them for the skyrocketing (and imaginatively less constrained) comic book industry of the late 1940s and early 50s. In each case, however, Wolverton was satirizing many of the serious genres that dominated pulp magazines, B-movies, radio and comic books themselves. Wolverton clearly is channeling the screwball tradition of Milt Gross, Rube Goldberg and Bill Holman. The zany physical antics propel the action, the wisecracking asides and slang fill most panels and the cultural stereotypes rain in hot and heavy. The foreshadowing of MAD magazine’s satirical approach is unmistakeable. This volume also has excellent annotations adding context to each reprint as well as an outrageous article by Wolverton himself on sound effects in the comics. This one is a treat.

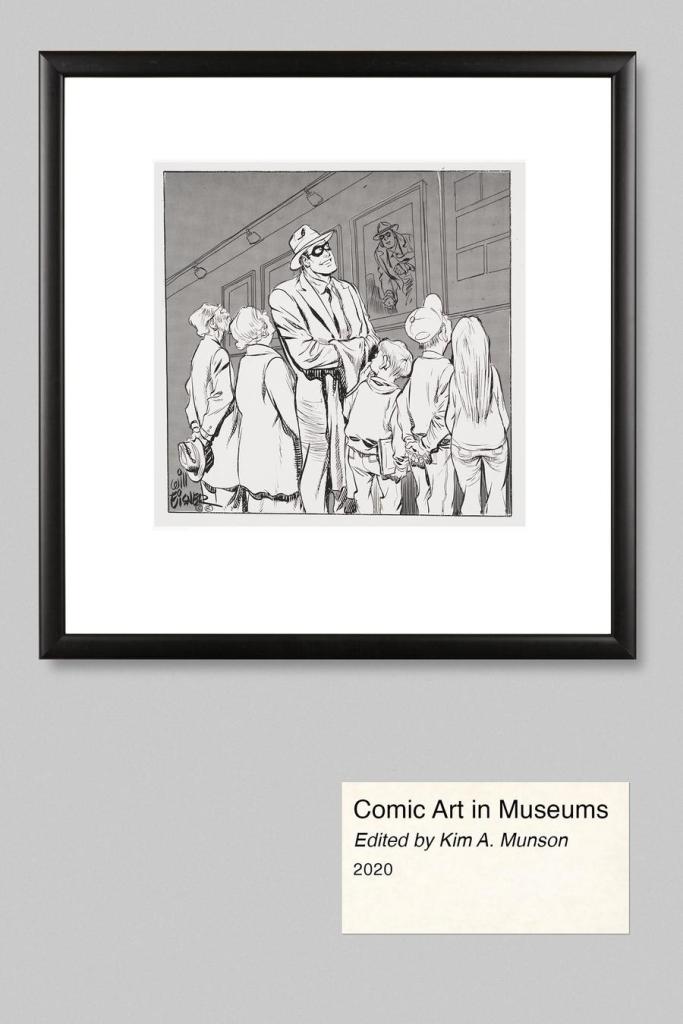

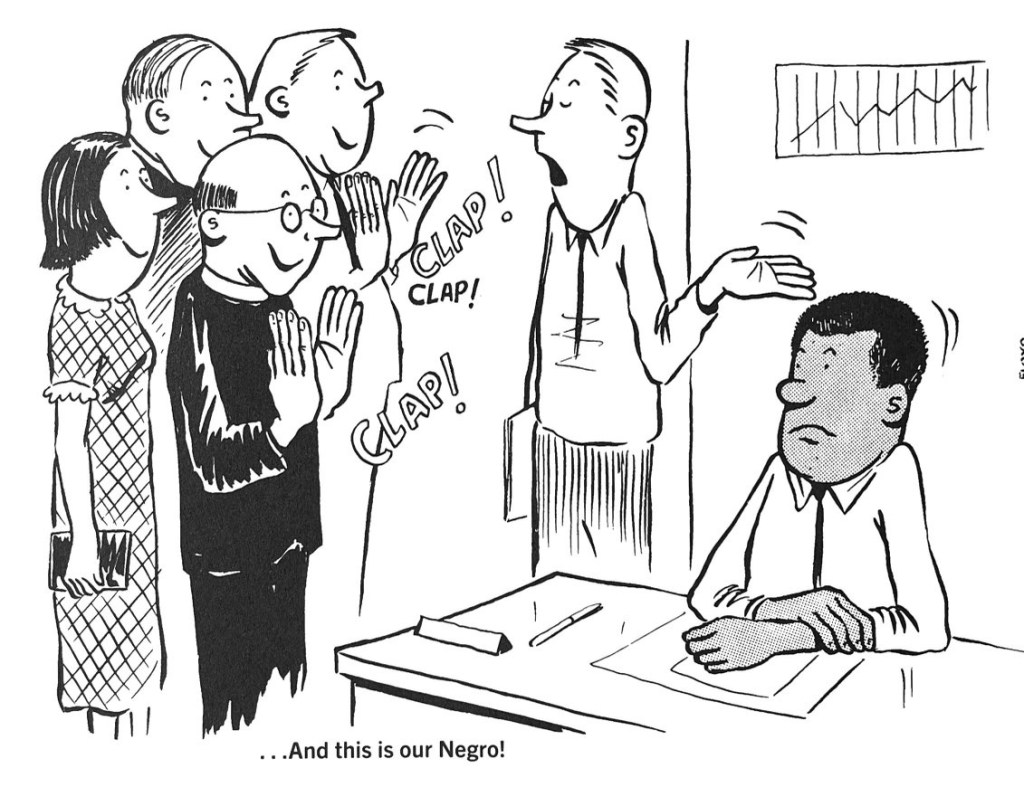

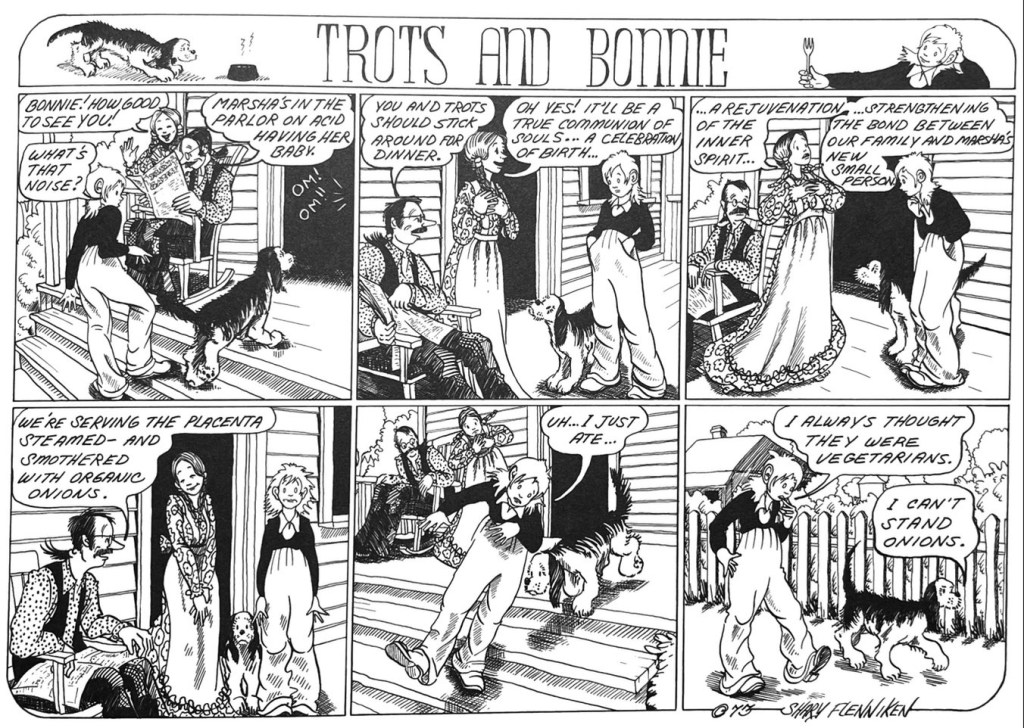

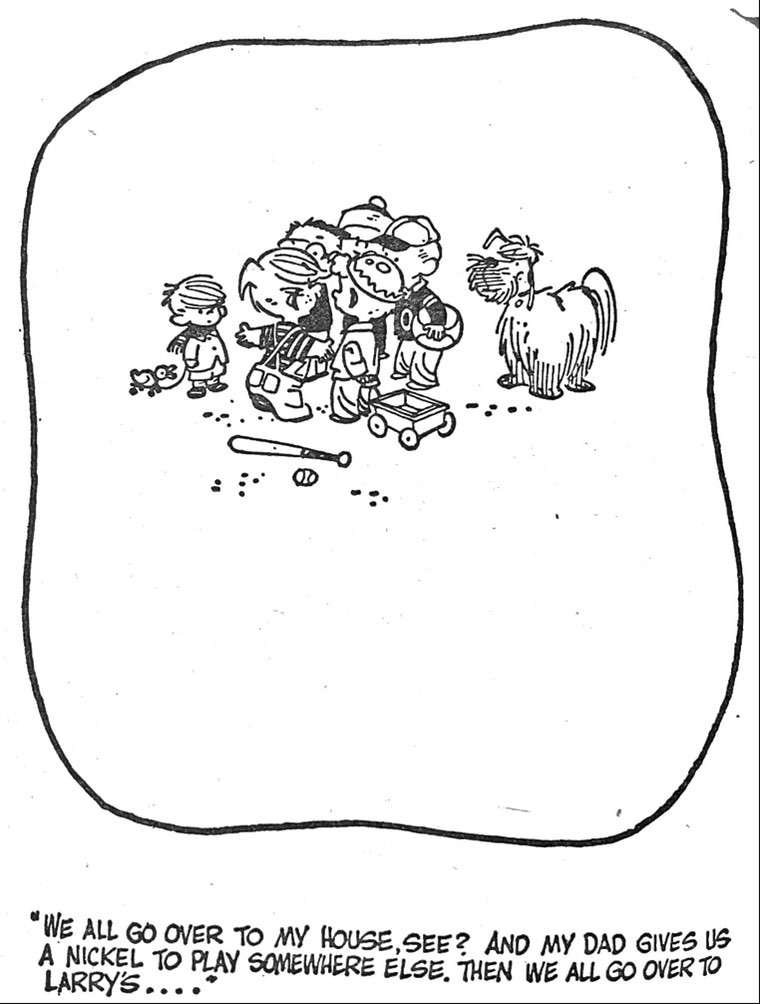

But Is It Art?: Comic Art in Museums

How “seriously” should thoughtful critics and audiences take the comic arts? That question seems to have dogged the cartoon arts since its earliest decades when pioneering pop culturists like Gilbert Seldes wrote extravagant defenses of the new medium. I confess that at this point in my five-decade run writing about mass media of all sorts, I find the relentless defensive justifications of pop culture criticism tiresome. And yet, that story of begrudging acceptance of the popular arts as “art” is its own important subject. One entryway to comic strip history is how the form has been regarded critically over the generations. Kim A. Munson’s Comic Art in Museums (University Press of Mississippi) is not as narrowly focused as its title suggests. While Muson provides a chronological framework and extensive introductory and connective matter, the book is really an anthology of writings by everyone from M.C. Gaines in 1942 to Denis Kitchen, Brian Walker, as well as multiple academics reflecting on the evolving reputation of the medium. I am still making my way through the densely packed book, but can already recommend it as a trove of insight and historical anecdote.

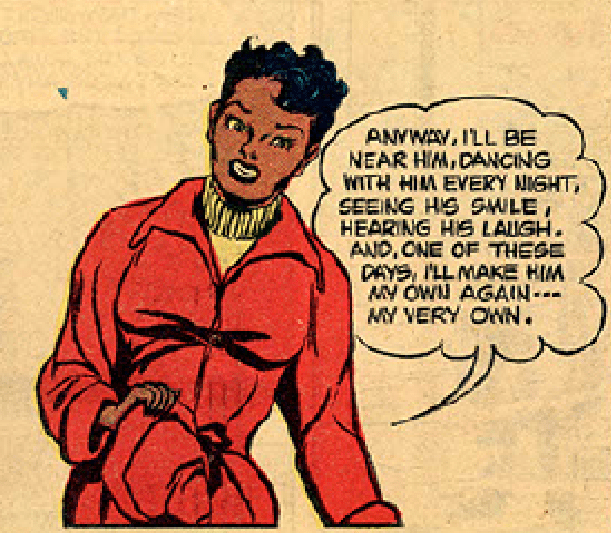

Johnny Hazard Sundays: Caniff Lite

All due respect to Johnny Hazard fans, it is hard to recommend Frank Robbins’ 33-year run as more than competent, middle-list comic strip fare. All of the luminaries also working at its height, Raymond, Caniff, Drake are considerably more interesting in their basic artistry, composition, storytelling. That said, this first oversized volume of Johnny Hazard Sundays does make the case for Robbins’s talents, even though his more mature work of the 1950s was obviously better. He had a strong sense of characterization, especially through facial expression. The moody use of coloring comes through even though some of the copies restored here were mediocre newsprint. And honestly I would have liked more background on Robbins and the thinking behind the strip rather than the intro pieces on his later DC Comics art. Still, Johnny Hazard Sundays Archive 1944-1946 (Hermes Press) gives us a 12X17 supersized reproduction of the Sunday adventure comics experience that is always welcome.

Kurtzman’s Wry Eye

Fantagraphics’ EC Library comes at the often-reprinted EC Comics of the early 1950s in black and white volumes organized by artist. Al the previous volumes have applied a lens onto the evolution of Wally Wood, John Severin, Johnny Craig, Al Feldstein, et. al. But this Man and Superman and Other Stories featuring Harvey Kurtzman before he took over the war titles and pioneered MAD really stands out for increasing our appreciation of this seminal comics artist. Kurtzman is among a handful of comics artists who were not just seminal within the medium but also to the general culture. The pop culture satire he codified in MAD magazine in the early 1950s applied a lens to post-WWII American mass culture that shaped generations of artists and even activists. This volume includes his earliest work for EC’s sci-fi, crime and horror stories. And they all show Kurtzman’s parodic attitude towards each of those genres. Tales like “Man and Superman,” “The Time Machine and the Schmoe!” and “Television Terror” took a light-hearted, even satirical take on the sci-fi and horror staples that drove the rest of the pages of these books. Most of these stories are written by the artist and so less wordy than over scripted tales the Feldstein foisted on most of the EC stable. These embody Kurtzman’s growing understanding of the relationship between word and text in the medium. He loves for high-minded science to go comically awry, along with the petty ambitions of everyman. The wry view of human foibles and hubris, which would inform the morality of his war stories and the satire of MAD, are all being rehearsed in these stories. Already sharp is Kurtzman’s mastery of of the comic form. He thought in panel progressions and the arc of a full page in ways far ahead of most artists. His compositions, use of foreground and background, the sense of motion as the eye moves across the panels, all are as fresh today as they were more than a half century ago.

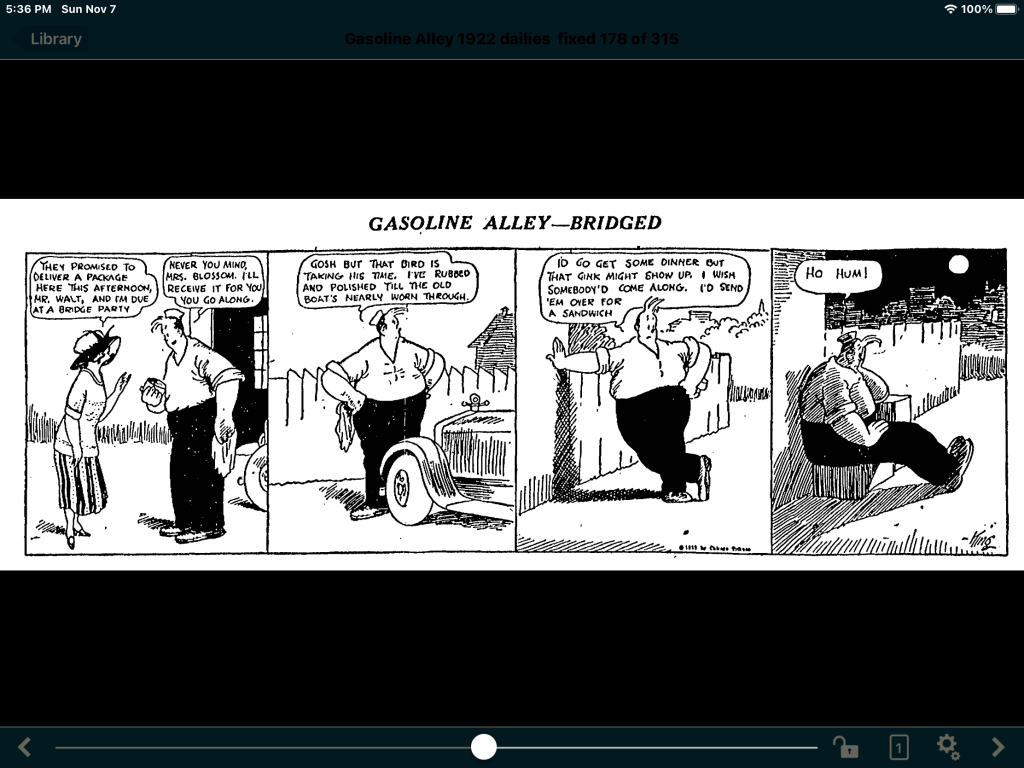

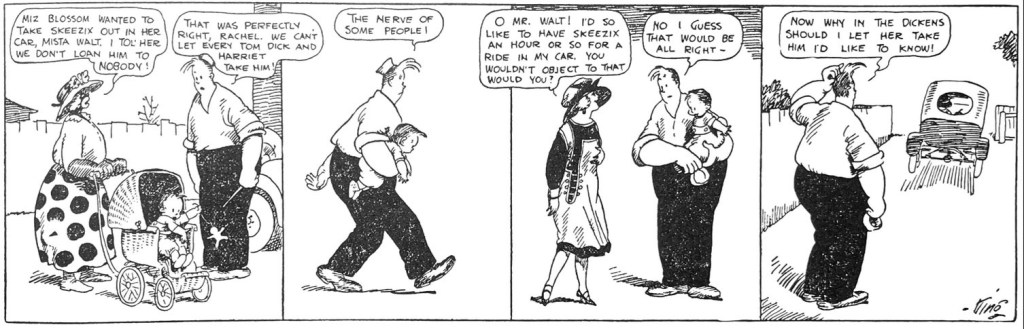

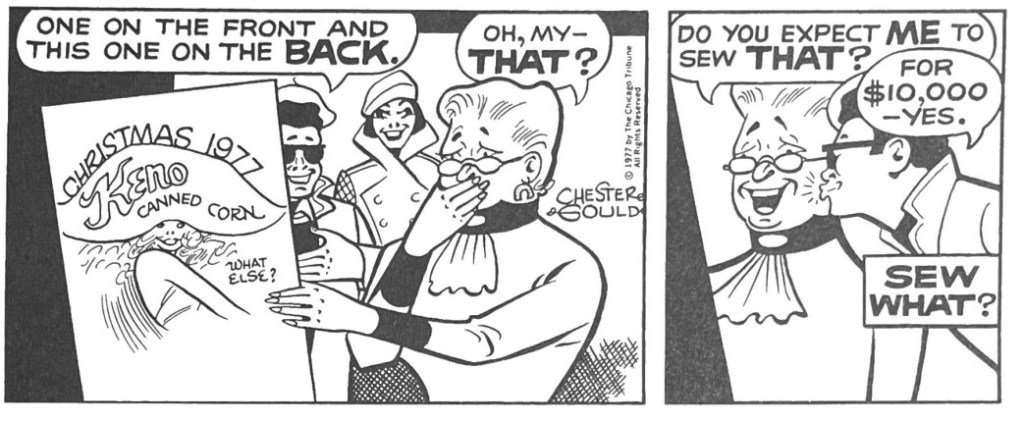

Chester Gould Takes a Bow

A number of ongoing reprint series had notable additions in the last year or so that call attention to the great work some publishers have been doing to keep the history of comic arts alive. In 2006 the Library of American Comics started an ambitious project to reprint Chester Gould’s full 1931-1977 run of Dick Tracy. With Volume 29 of The Complete Dick Tracy, LOAC finished one of the largest, complete comic strip reprint project, second only perhaps to Fantagraphics’ Peanuts project. I already reflected on Gould’s run and the way he ended the strip. The final volume speaks to what a canny master of comic strip art and business Gould really was. As newspapers shrank the canvas, he adjusted and rethought his signature style accordingly. And while the later years of the strip are remarkably different in look and feel than its first decade, the wild imagination, bizarre villainy, wonderfully improbable chases and escape remained central to a Dick Tracy story arc.