It is way past time to review and highlight some of the noteworthy books for comic strip mavens in the last year. For nearly a decade, as an editor at media trades Media Industry Newsletter and then Folio magazine, I did annual roundups of books of special interest to print media professionals. Historically significant comics reprints always played in my mix. Following the diminishing fortunes of the magazine industry in recent years, MIN merged with Folio, which itself folded into oblivion in late 2019. And so I moved the 2019 roundup here to Panels & Prose. I never got around to doing a 2020 edition, because, well, 2020. So over the next week or so I will be calling out my faves from last year and so far this year that I think furthered our understanding of comics history. Today we start with the one title in the bunch that nudges beyond the usual focus of this site on newspaper and magazine comics. But the magnificent legacy of EC is too important a milestone in the American comic arts to exclude.

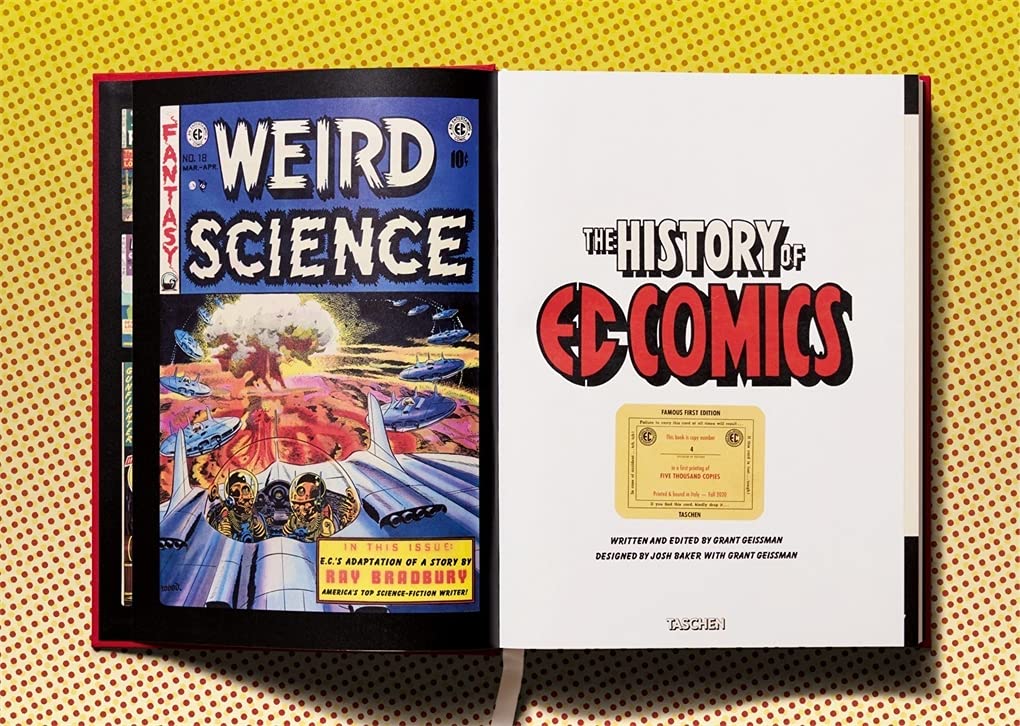

The History of EC Comics

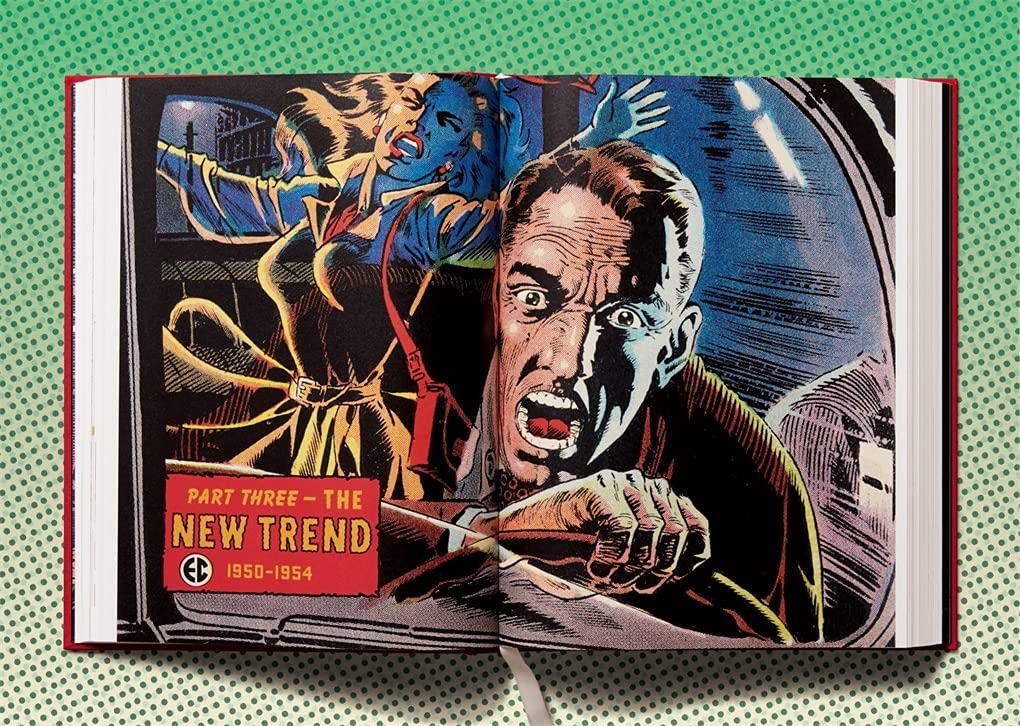

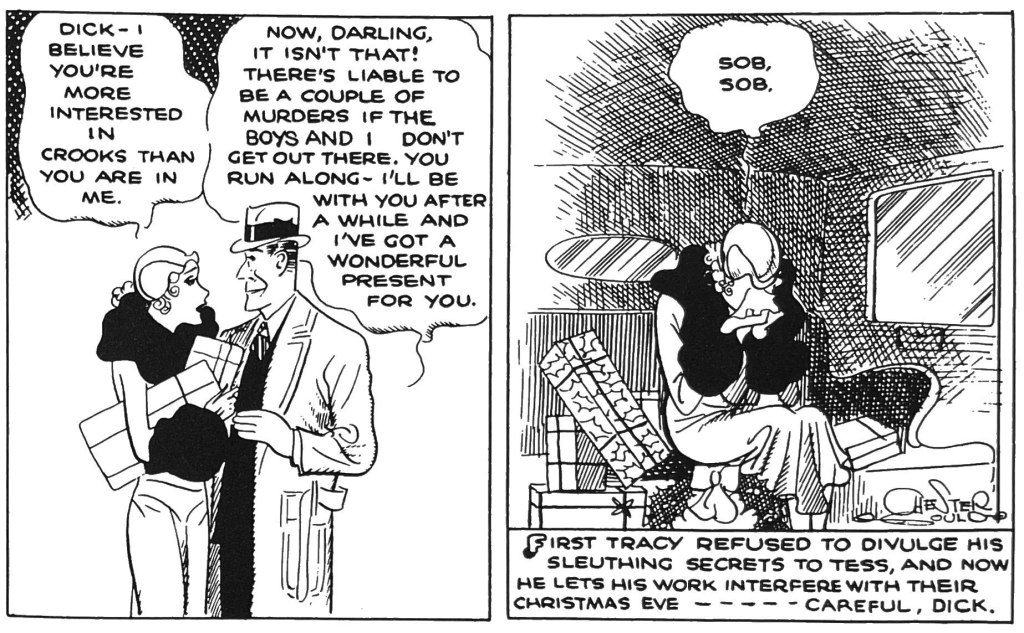

The annual cinder block from Taschen for comics fans is Grant Geissman’s The History of EC Comics, a massive reflection on and reprinting of the greatest collection of comics artists in history. William Gaines’ EC horror, war and crime comics was the home of Tales from the Crypt, Weird Science and Frontline Combat. Like all Taschen books the sheer scale allows Geissman to pour in full story reprints, some in original art, memos, office photos, even contracts that help bring to life the familiar history of this incredible stable of talent. It is hard to go wrong with a book brimming with Jack Davis, Wally Wood, Harvey Kurtzman, Johnny Craig, Al Feldstein, Will Elder, just to name-drop a few. Falling into these artists at 14×18 scale is a revelation, even to lifelong fans like me. The book also has an end section reproducing every EC cover where many of these artists hit their peak. Kudos to Geissman’s curatorial skill.

The text history is not as compelling. I think Geissman’s rendering of Bill Gaines’s father, comic book pioneer Max Gaines, is quite good. It has telling detail and foreshadows the psychic burden Bill carried. Otherwise, however, Geissman defers to others for the scant aesthetic evaluations of all this great artistry he has assembled here. Nor is there much about the tropes, themes, attitudes and visual conceits that a more curious and creative interpreter might tie to the zeitgeist. Tashen’s other recent XXL titles on Krazy Kat and Little Nemo, both benefitted greatly by Alexander Braun’s critical acumen. Appreciating and distinguishing among comics styles was central to EC’s success, because publisher Gaines and editor/writer Feldstein meted out the freelance work according to whose style fit the story. This layer of interpretation is missing here. Instead, the history and ancillary images are guided by a collector’s penchant for later market value and rarity rather than aesthetic or cultural significance.

Nit Picky? Not for a tome that is priced and positioned as definitive. Sure, one wishes that such a visually generous and lush, let alone expensive, book on EC was a full-throated celebration and genuine interpretation of its artistry. We’ll settle for this.