Jimmy Hatlo’s They’ll Do It Every Time (1929-2008) was as long-lived and beloved as it was throughly benign. To be fair, this single-panel museum of petty grievance had banality baked into its title and premise. The actual identity of the “they” is kept usefully loose enough to encompass an “other” of our choosing, but most likely all of humanity but us. And their “doing it every time” is by definition rote and predictable. But of course it is the aching familiarity of Hatlo’s observations that gave the strip purchase. Widely praised for poking at the small hypocrisies, human foibles, bombast of everyday existence, the strip had a special populist appeal. Hatlo was inspired by readers who submitted ideas and got daily credit with a “tip of the Hatlo hat” and even their name and street address for millions to see. Indeed, that was a vastly different era when it came to personally identifiable information. And yet, not so ancient. We can see in They’ll Do It Every Time predecessors of both user-generated content (UGC) and observational humor.

Continue readingTag Archives: 1940s

Campbell’s Cuties: Wartime Women Had Their Moment

The role of WWII in the history of women, equality and feminism in America is widely known and usually mythologized in Rosie the Riveter tales. With many men abroad, women filled roles in industry and management that typically had been denied them. According to the thumbnail version, newly empowered women suffered a kind of cultural whiplash with the post-war return of men to the States. Industry, government and pop culture generally actively discouraged women from enjoying their newfound role outside of the home in range of unseemly ways.

Continue readingQueer-Coding A La 1948: Buz Sawyer Flexes His Pecs

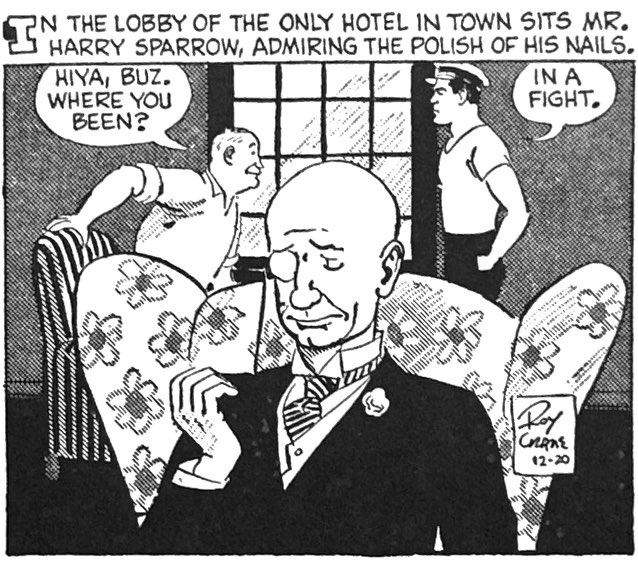

The sublimations of the American comic strip are legion. Whether it is the unbridled eroticism of Flash Gordon or the beefcake of Prince Valiant, the kinkiness of The Phantom or the stripteasing of Terry and the Pirates, the most “innocent” of modern American mass media contained many quiet erotic sub-texts for horny readers across ages and sexes. Case in point, Buz Sawyer in the 1940s. I have no idea what was going on with Buz’s artist Roy Crane and writer Edwin Granberry in the 1947-48 years, but the strip seemed a bit obsessed with gender-bending, sexual stereotypes and masculine identity across storylines in those years. In two adjoined episodes, our two-fisted hero deals with the barely-veiled advances of an effeminate gun-runner and sexual harassment at the hands of a masculinized female Frontier executive. This is one of those many cases where the most reserved and adolescent of modern media, the family newspaper strip, traded in suggestive imagery and innuendo that would never pass muster in other media of the day.

Continue readingRoy Crane: Shades of Genius

Roy Crane doesn’t seem to garner the kind of reverence held for fellow adventurists like Milton Caniff and Alex Raymond, even though he pioneered the genre in Wash Tubbs and Capt. Easy. Perhaps it is that he lacks their sobriety. After all, Crane evolved the first globe-trotting comic strip adventure out of a gag strip about the big-footed, pie-eyed and bumbling Tubbs. But when he sent Wash on treasure hunts and international treks into exotic pre-modern cultures he kept one foot in cartoonishness style and the other in well-researched, precisely rendered settings, action and suspense. It was a light realism, with clean lines, softly outlined figures, often set in much more realistic panoramic backgrounds. This was not the photo-realist dry-brushing and feathering of Raymond, nor the brooding chiaroscuro of Caniff.

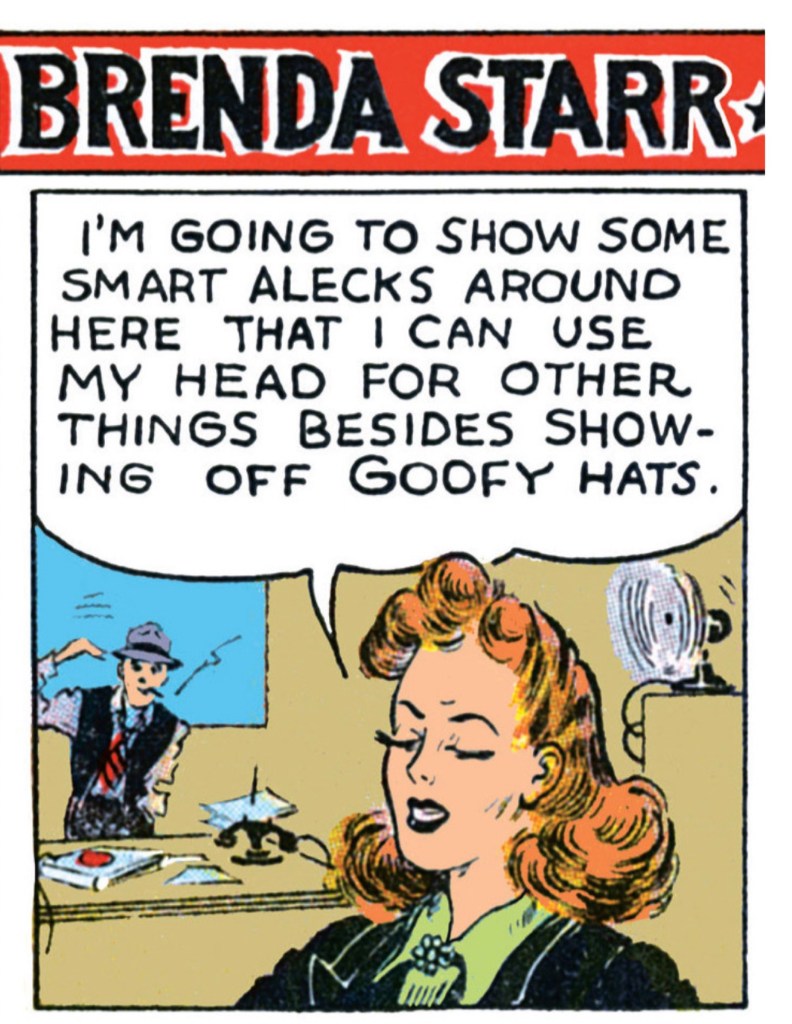

Continue readingBrenda Starr Comes Out Swinging

Like its eponymous heroine, Dale Messick’s Brenda Starr strip had to conquer the systemic sexism of the newsroom to make her mark. It launched in 1940 in constricted, Sunday-only syndication under the skeptical stewardship of New York Daily News legend Captain Joseph Patterson, after he had rejected Messick’s multiple submission for female-led adventure strips. According to lore, Patterson was unabashed in dismissing women in cartooning, claiming to have tried and failed with them in the past, “and wanted no more of them.” Messick’s samples were salvaged from the discard pile by Patterson’s more open minded assistant Mollie Slott, who helped the artist rework her ideas to feature an ambitious and dauntless female reporter. The artist was acutely aware of the gender deck stacked against her. Born “Dalia” Messick, she deliberately adopted the androgynous “Dale” to help get her strips considered more seriously. Slott convinced thge reluctant Patterson to give this red-headed firebrand and Rita Hayworth lookalike a try. History was made.

Continue readingChester Riley, Al Capp, and Dr. Wertham: The Great Comics Crisis of…1948?

Conventional wisdom holds that the infamous moral panic around crime and horror comics bloomed in 1953 with the popularization of Frederic Wertham’s dubious “research” in general magazines and the formation of Senate subcommittee on juvenile delinquency. But the proliferation of Wertham’s landmark Seduction of the Innocent (1954) diatribe against comics, and the haranguing of Senators Kefauver and Hendrickson was just the culmination of a controversy that had accompanied the rise of more adult and violent comic books throughout the 1940s. Parents worried about the bullets and blood that flew across the color pages of blockbuster titles like Crime Does Not Pay and its many imitators long before the EC titles and their followers horrified parents and legislators even more.

Continue readingBest Books of 2022: Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos

Bungleton Green was the longest running comic strip in the history of American Black newspapers, and an extended reprint of its greatest, wildest period during WWII is long overdue. But New York Review Comics has come through with this well-designed volume embracing artist Jay Jackson’s 1943-1944 sequence Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos. The strip began in 1920 with Leslie Rogers’ rendering of his eponymous character as a comic shirker, gambler and goof in the model of Moon Mullins or Barney Google. When the Chicago Defender’s prolific cartoonist Jay Jackson took the reins in the early 1930s, he made Bungleton into more of an adventurer, riding a genre that dominated the 1930s with Dick Tracy, Terry and the Pirates, Flash Gordon and Little Orphan Annie. Meanwhile, Jackson was also freelancing artwork for the science-fiction pulps and honing his skills as a “good girl” artists, skills that would soon inform a major turn in his weekly strip work.

Continue reading