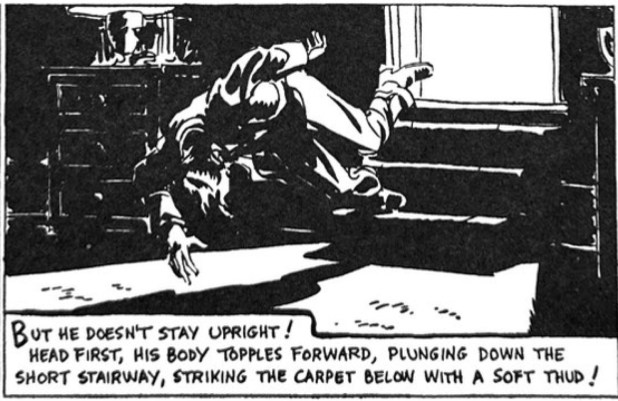

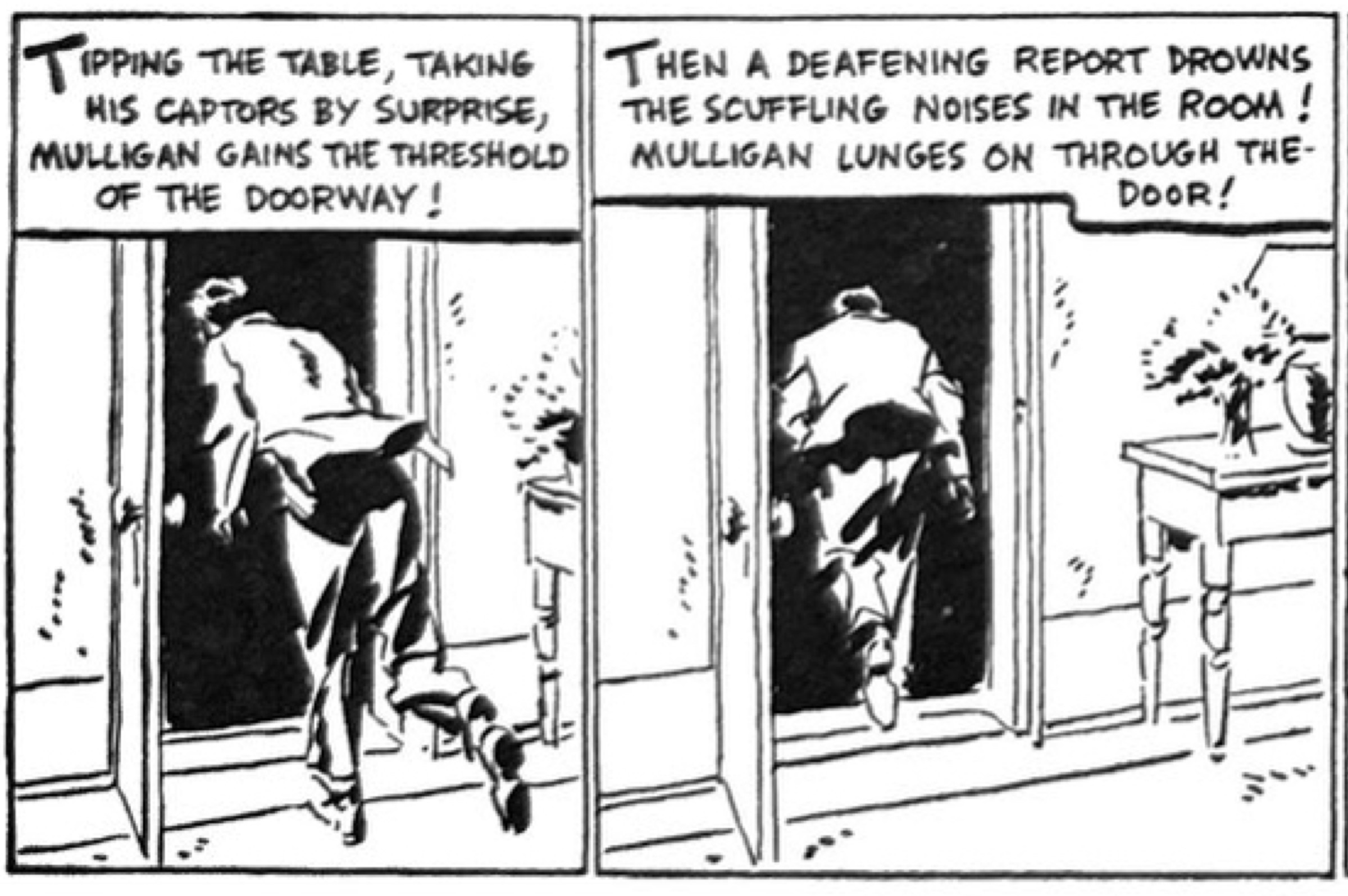

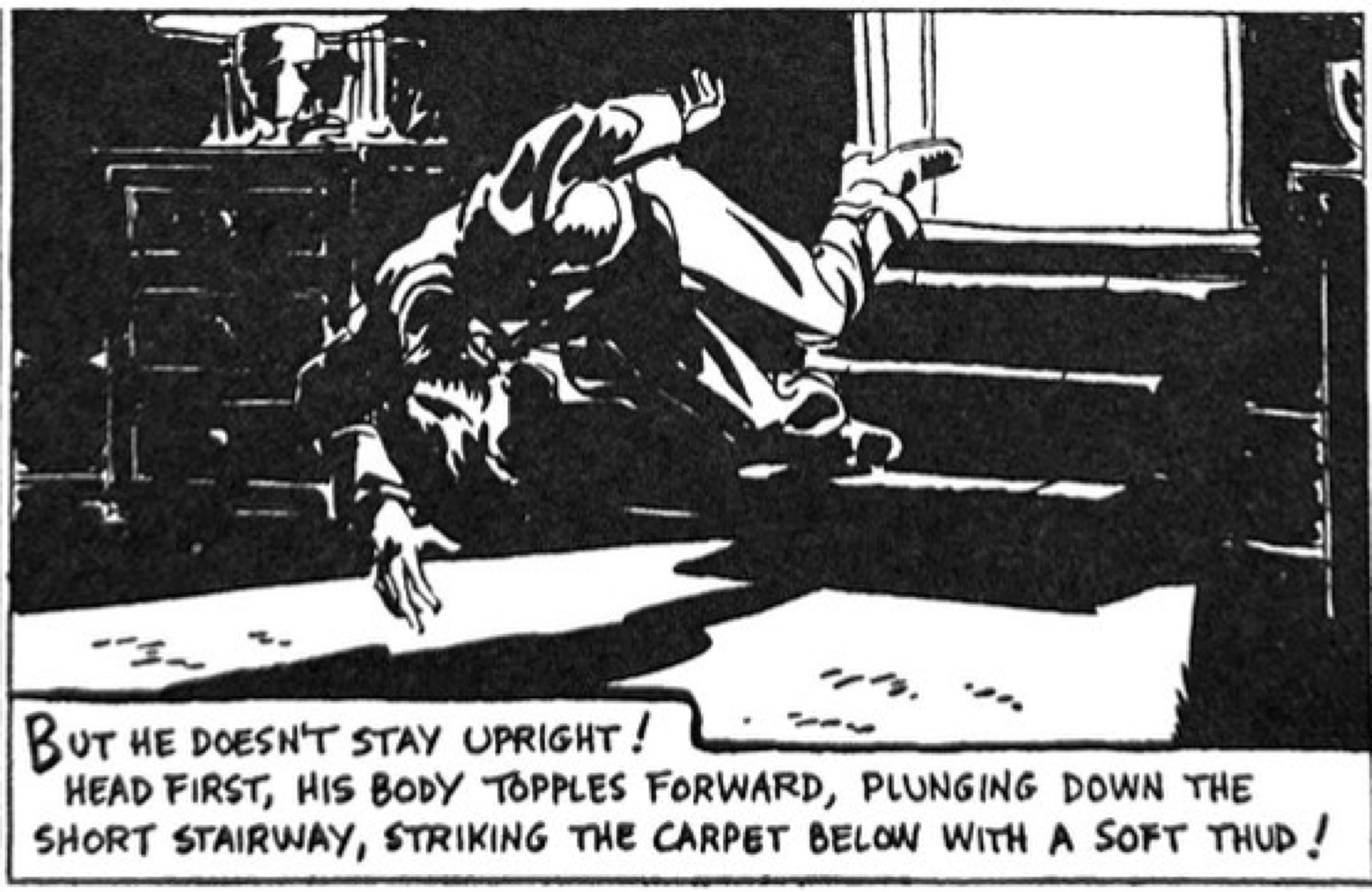

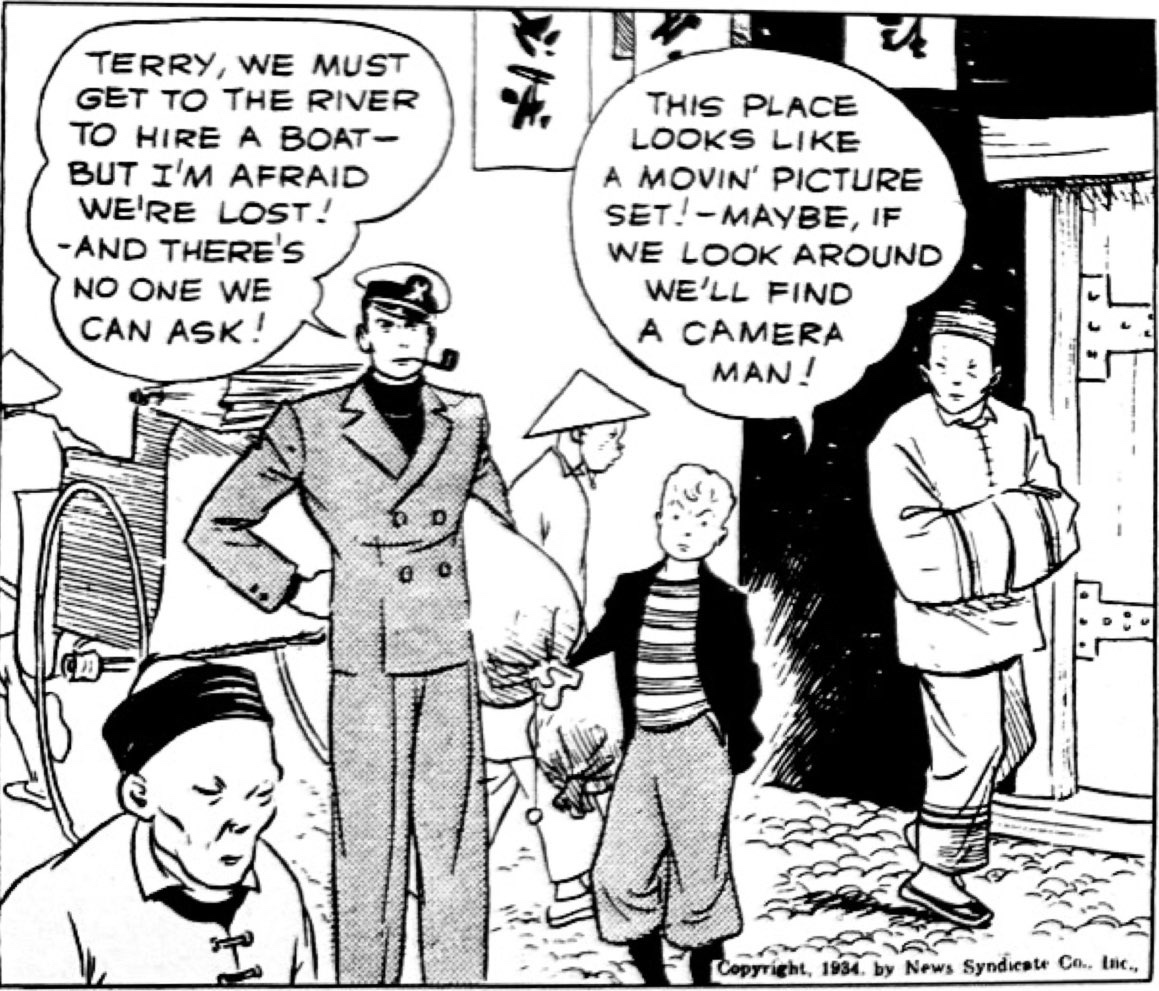

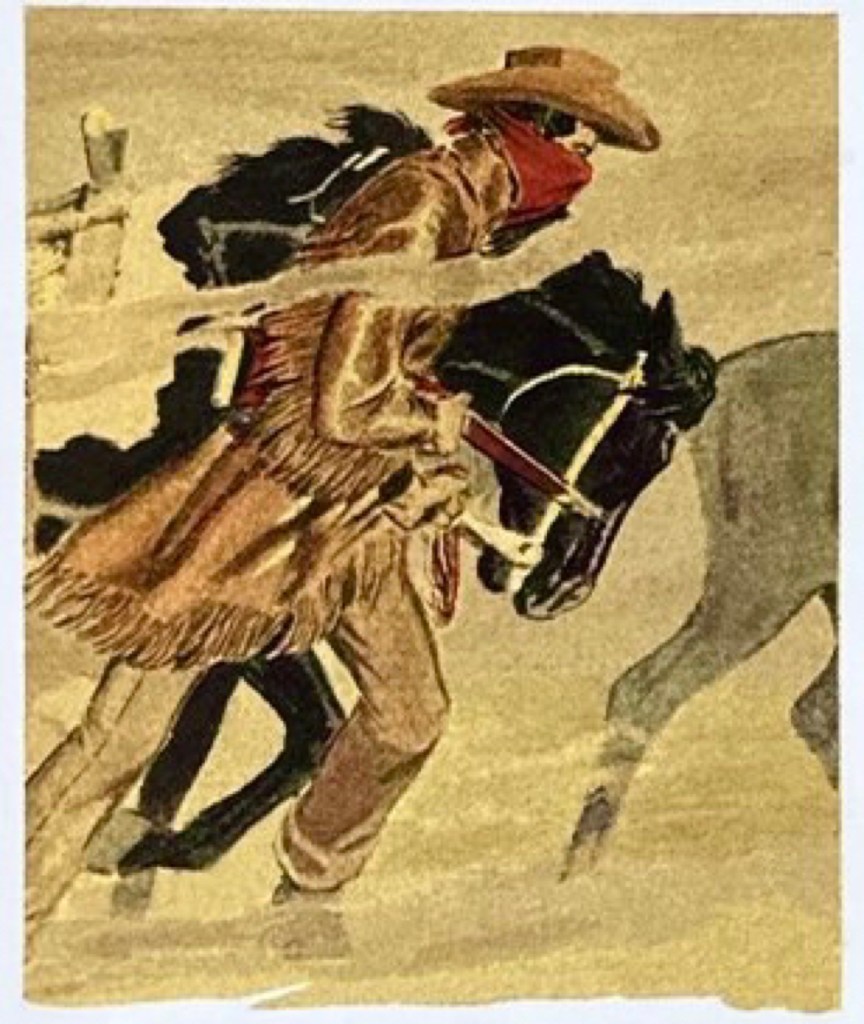

I admit to coming late to appreciating Noel Sickles’ artistic prowess and influence. Several years ago I found an affordable but beaten copy of the LOAC volume on the artist and his short, legendary stint on the Scorchy Smith strip in the mid 1930s, though I barely cracked it at the time. Sickles is best recalled by comics historians as Milton Caniff’s friend, studio-mate and collaborator who introduced the more famous artist to the chiaroscuro style that came to define Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon. Sickles himself spent but a few years leading his own strip before moving on to a lucrative career in commercial art, magazine and book cover illustration.

Now that I have dug into the LOAC Scorchy Smith reprint, with deft commentary/background from Jim Steranko and Bruce Canwell, I am gobsmacked by how thoughtful a talent he was. Moreover, his trail of influence reaches far beyond Caniff.

Continue reading