“But the [comic] strip has suffered from mass production and humor hardening into formula…. It has sacrificed its original spirit for spurious realism.” – “The Funny Papers”, Fortune Magazine, April, 1933.

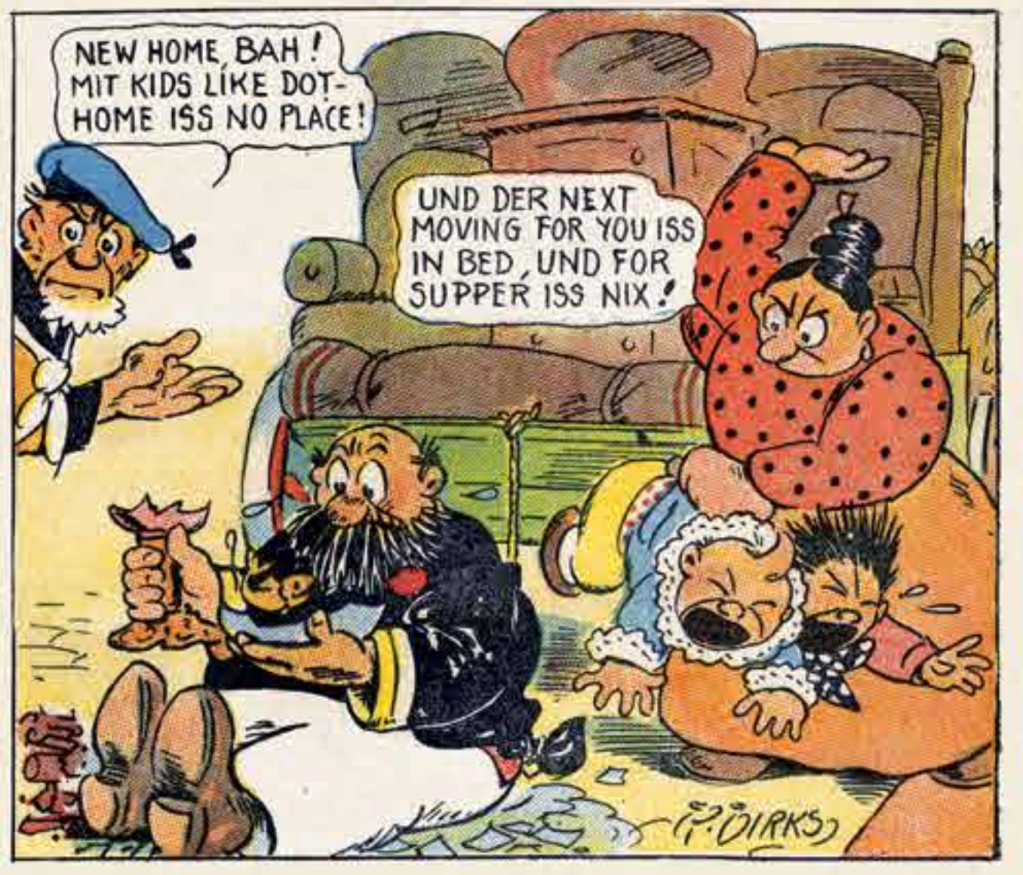

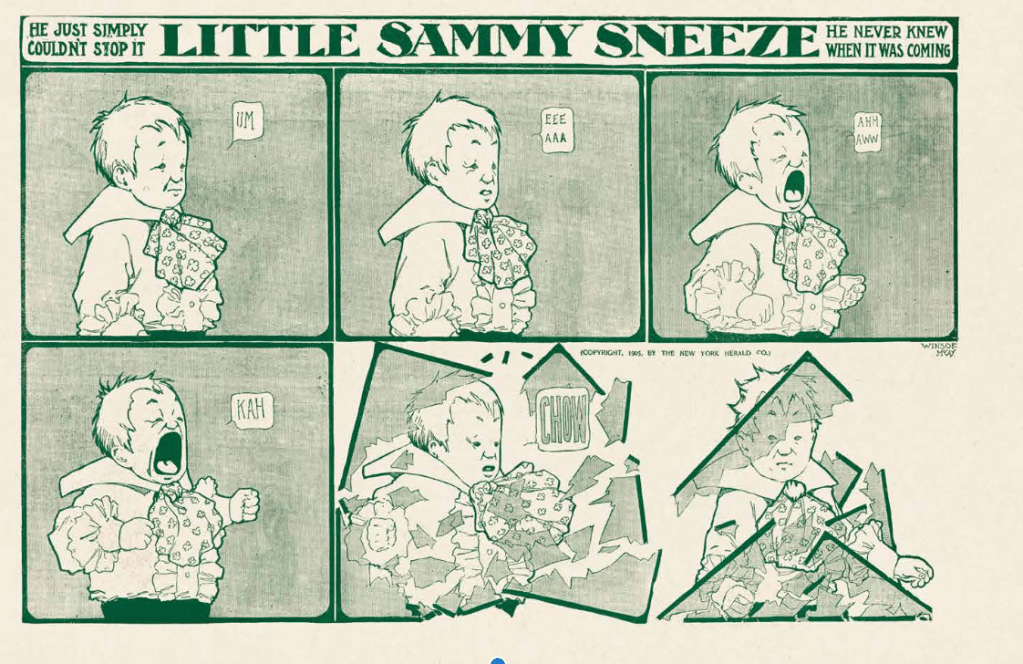

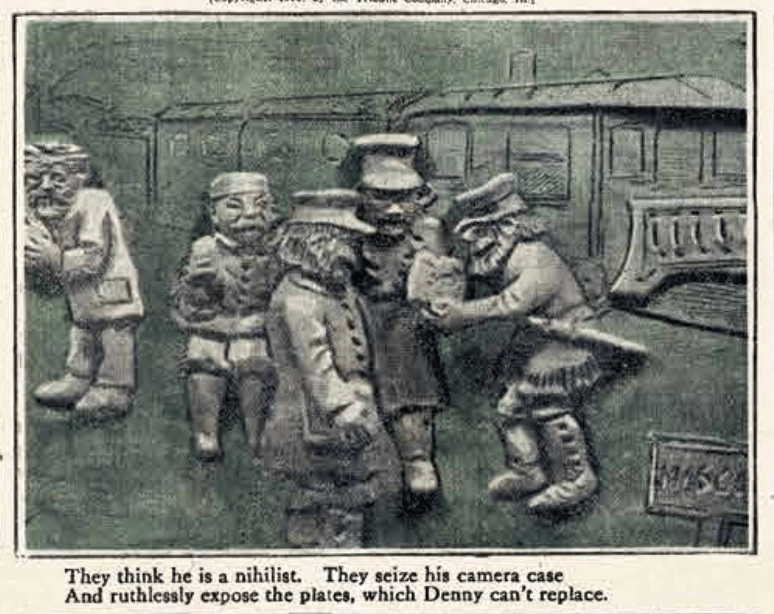

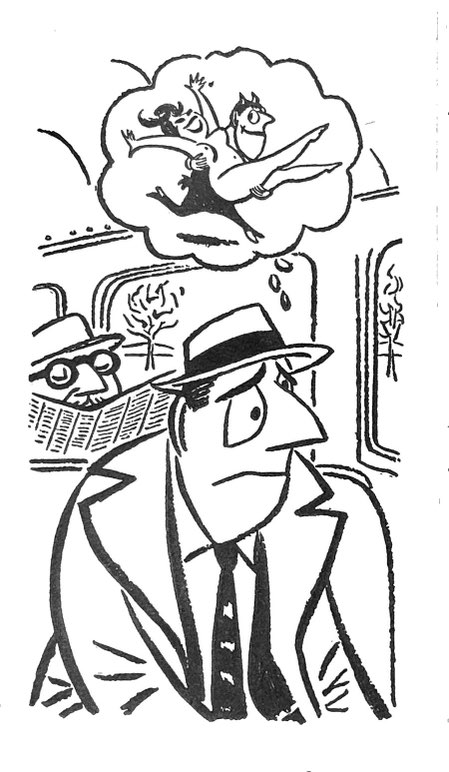

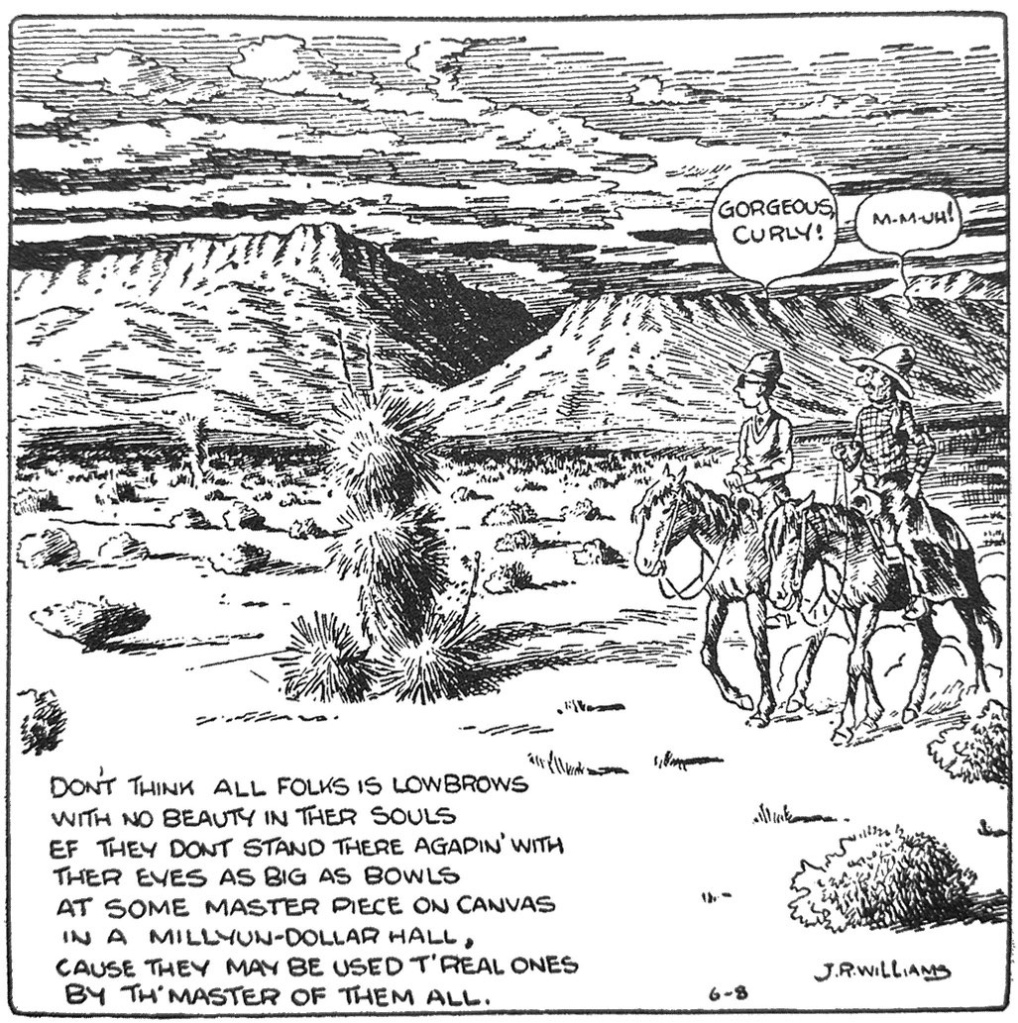

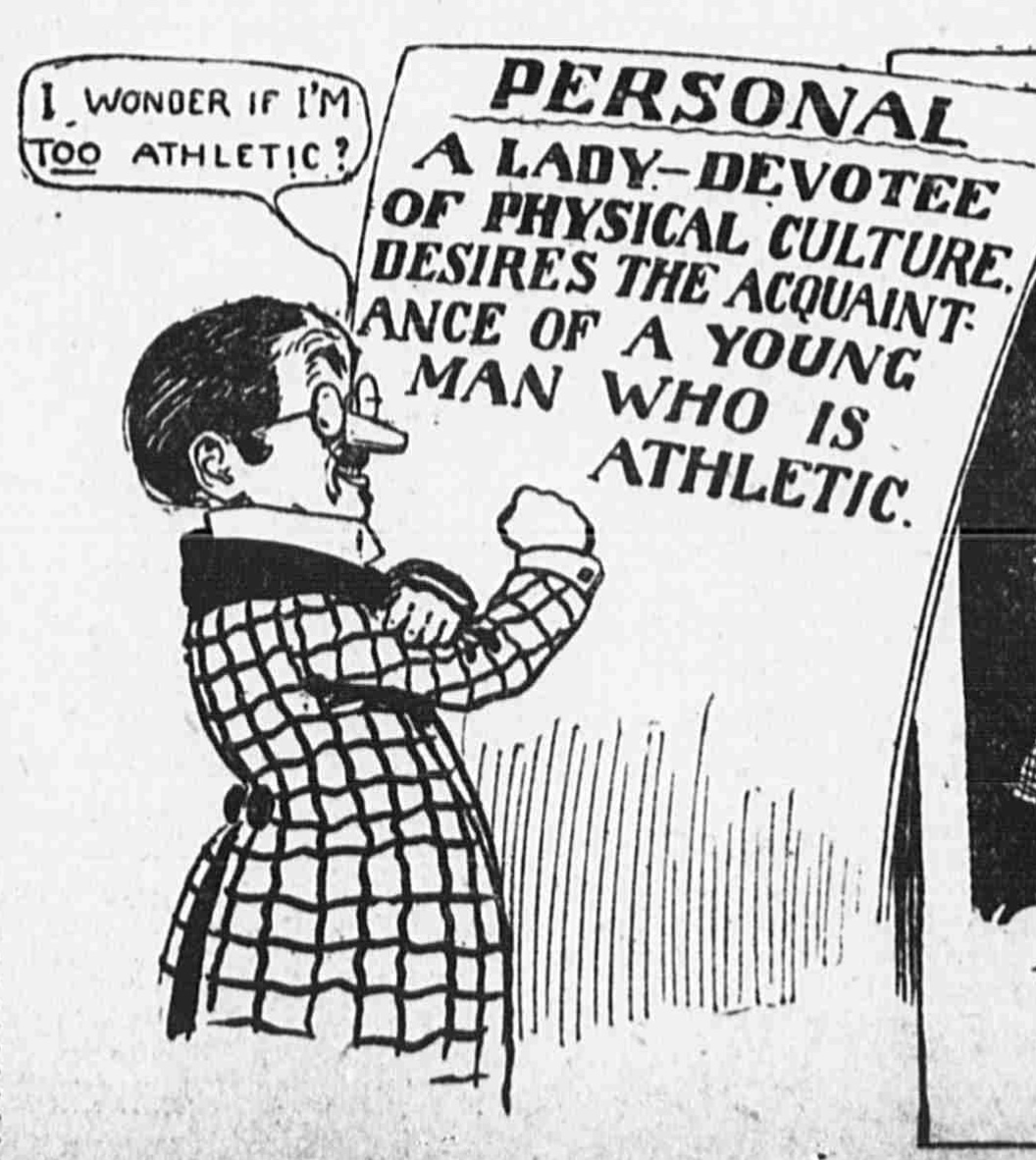

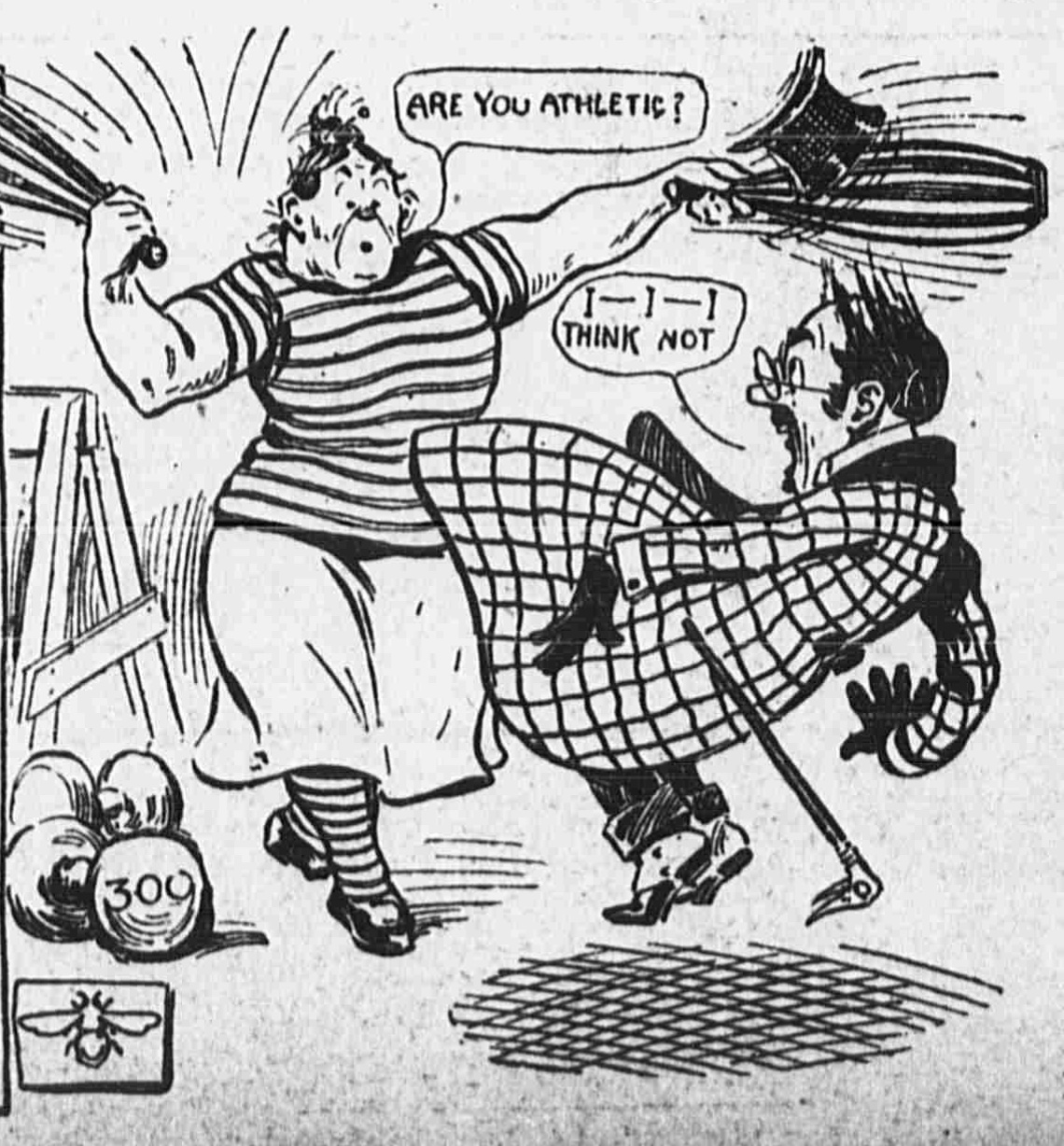

Who could say such a thing in 1933, just as Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy, Buck Rogers, Tarzan and Terry were about to launch what many consider a “golden age” of American comic strips? But in a major feature in its April 1933 number, Fortune magazine lamented the new adventure trend as a sign of the medium’s decline. In their telling, comics were losing an antic, satirical edge that had distinguished them from the gentility of American literature or saccharine romance of silent film. In particular, the Fortune piece (unattributed so far as I could tell), bemoaned the rise of the dramatic “continuity” strip in place of gags. They single out Tarzan in particular as a corporate product that suffers from too many scribes and artists not working together. “The strip wanders through continents and cannibals with incredible incoherence,” they say. And to be fair, who could have foreseen in 1933 that Flash, Dick, Terry and Prince Val were about to redirect the “funnies” from hapless hubbies and bigfoot aesthetics towards hyper-masculinized heroism and a new realism that readers found far from “spurious?”

Continue reading