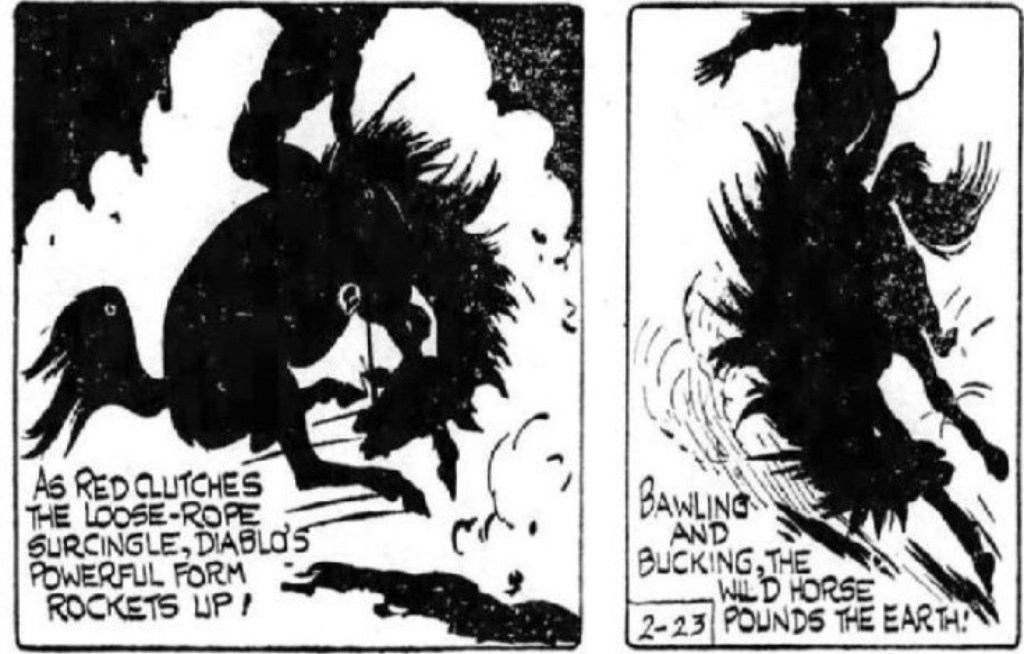

One of the longest-lived and popular Western series of the last century, Red Ryder (1938-1965) is barely remembered today…mostly for good reason. Unlike richer, historically-informed efforts like Warren Tufts’ masterful Casey Ruggles and Lance, Red Ryder was closer to Western genre boilerplate, The titular hero is a red-headed journeyman cowpoke who finds and resolves trouble wherever he roams. His woefully typecast sidekick “Little Beaver” was an orphaned Native American boy who provided identification for kid readers, a sounding board for the solitary and stoic Red, and comic relief of a distinctly stereotyped sort. In truth the strip made little effort to delve into character let alone suspense or high adventure.

Continue reading