E.C. Segar seemed to love the screwball monarchy set piece that captivated 1930s comedy. He used the premise of the madcap cartoon kingdom at least three times: once in the early 30s defending Nazilia, later in the 30s when he installed Swee’Pea as a king, and most notably in the sailor man’s founding of his own kingdom of Spinachova in 1935. Starting on April 22, 1935 with Popeye’s decision to build an ark and ending with him abandoning the utopian venture in defeat and disgust on March 19, 1936, Popeye’s act of radical escape from Depression-Era America was among the longest continuities in the history of Thimble Theatre. But the Spinachova epic was important in a number of ways. It was the closest Segar came to political satire. The tension between “dictipator” Popeye and his “sheep” (the people) is basically a political one that turns the trendy populism and folk romanticism of the day on its head. It was also a saga of defeat for Segar’s hero, an extended example of our otherwise heroic, even super-powered folk moralist showing all manner of very human weaknesses. And finally, most importantly perhaps, the episode was Segar at his absurdist peak, a tour de force of relentless zany side trips, inane situations and surreal resolutions that were the cartoonist’s hallmark. While Thimble Theatre’s Plunder Island storyline was likely Segar’s most successful continuity in developing character, plot and comic suspense, he was using the roomier canvas of Sunday pages for deeper, more immersive sequences. The Spinachova saga was executed across nearly a year of dailies, which may give us the fullest picture of this artist’s range within the truncated cadences of this format.

Continue readingTag Archives: comics and culture

Buck Rogers Solar Scouts: “An Asset to My Parents, My Country”

Toy ray guns and spaceships, cereal premiums, and radio shows spun off from Buck Rogers’ phenomenal popularity in the 1930s. The property was tailor made for merchandising and licensing, of course. Gadgetry was the strip’s core appeal. A number of comic strip’s created kid clubs around their heroes. Dick Tracy had his Detectives Club, and later the famous Crimestoppers. Little Orphan Annie’s radio show had its own Secret Society with a toy decoding device for over-air messages (famously depicted in the film A Christmas Story), and the strip enlisted her fans into Junior Commandos during World War II. In addition to servicing fans, keeping audiences engaged, these clubs were also early examples of marketing data collection, See for instance Buck Rogers’ Space Scouts application above. While some of the data inputs were tongue in cheek, of course, club applications

(“previous rocket ship experience”?), the club members promotions worked much like sweepstakes for other consumer product manufacturers, a way of getting first part data on their audience.

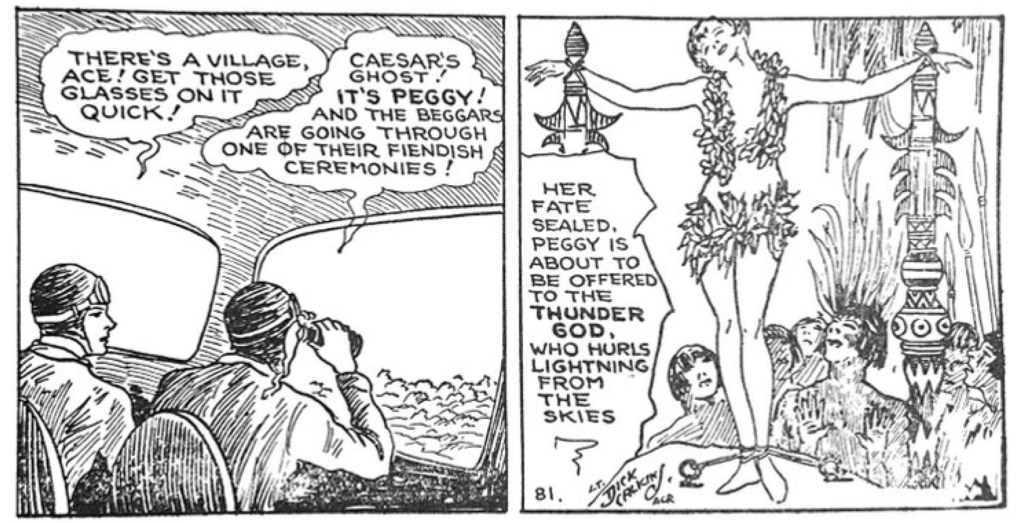

Skyroads: Flying As Fetish

After the fast success of Tailspin Tommy in 1928 from the Bell Syndicate, the John F. Dille company responded with Skyroads about five months after the syndicate introduced Buck Rogers. The otherwise forgettable strip is perhaps most notable as a stable for artists on more important projects.

Continue readingBoy Wonder: Tailspin Tommy’s Machine Romance

“Boy!! That’s the life for me. Gosh…” The first of the major aviation-themed strips, Tailspin Tommy (1928-1942) embodied many of the essential qualities of the genre. From its start, the strip had an infectious, boyish wonder…about the air, about technology, about modern progress itself. Like most in the category, it was drawn by a pilot and flying enthusiast (Hal Forrest) in a rough style that fetishized planes and flight images yet fell flat in depicting characters and earthbound life.

Continue readingDick Tracy Battles The JDs: Flattop Jr. and Joe Period

Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy was created in the 1930s as a response to the romanticization of gangsters and declining respect for law enforcement. And throughout its run under the notoriously conservative artist made no secret of his disdain for many modern trends. In the 1950s when mania around “juvenile delinquency” dominated popular culture, Gould added to his famous rogues gallery a few of these teen terrorists. Most notable for its outright weirdness (even for Gould) are the 1956 episodes spanning Joe Period and Flattop, Jr., the son of one of Tracy’s most famous nemeses of the prior decade.

Continue readingChester Riley, Al Capp, and Dr. Wertham: The Great Comics Crisis of…1948?

Conventional wisdom holds that the infamous moral panic around crime and horror comics bloomed in 1953 with the popularization of Frederic Wertham’s dubious “research” in general magazines and the formation of Senate subcommittee on juvenile delinquency. But the proliferation of Wertham’s landmark Seduction of the Innocent (1954) diatribe against comics, and the haranguing of Senators Kefauver and Hendrickson was just the culmination of a controversy that had accompanied the rise of more adult and violent comic books throughout the 1940s. Parents worried about the bullets and blood that flew across the color pages of blockbuster titles like Crime Does Not Pay and its many imitators long before the EC titles and their followers horrified parents and legislators even more.

Continue readingBest Books of 2022: Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos

Bungleton Green was the longest running comic strip in the history of American Black newspapers, and an extended reprint of its greatest, wildest period during WWII is long overdue. But New York Review Comics has come through with this well-designed volume embracing artist Jay Jackson’s 1943-1944 sequence Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos. The strip began in 1920 with Leslie Rogers’ rendering of his eponymous character as a comic shirker, gambler and goof in the model of Moon Mullins or Barney Google. When the Chicago Defender’s prolific cartoonist Jay Jackson took the reins in the early 1930s, he made Bungleton into more of an adventurer, riding a genre that dominated the 1930s with Dick Tracy, Terry and the Pirates, Flash Gordon and Little Orphan Annie. Meanwhile, Jackson was also freelancing artwork for the science-fiction pulps and honing his skills as a “good girl” artists, skills that would soon inform a major turn in his weekly strip work.

Continue reading